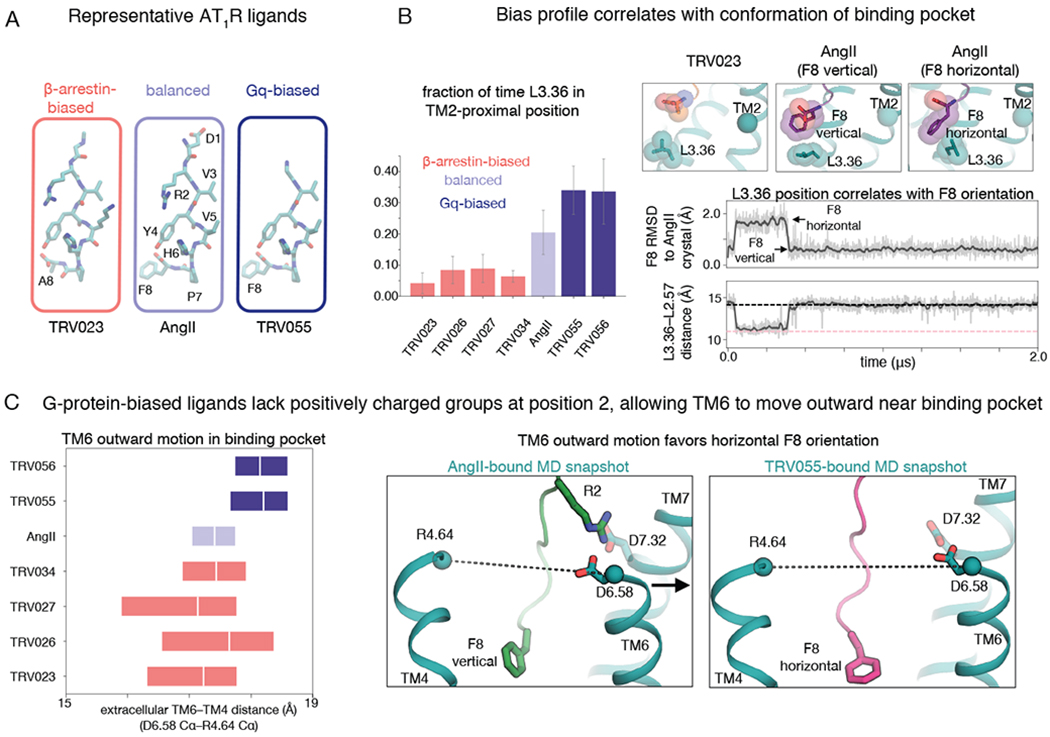

Fig. 4. Arrestin-biased, balanced, and G-protein-biased ligands favor distinct binding-pocket conformations.

(A) Structures of representative β-arrestin-biased, balanced, and Gq-biased AT1R ligands. All ligands studied in this work are shown in Fig. S1. (B) In comparison to β-arrestin-biased ligands, AngII drives L3.36 of the binding pocket toward its TM2-proximal position, which favors the canonical active conformation, and Gq-biased ligands do so even more (P = 0.002 for β-arrestin-biased vs. Gq-biased ligands; see Methods) (left; the bar plot shows means and standard errors across 5 independent 2-μs simulations per ligand). When the F8 residue of AngII and Gq-biased ligands adopts a horizontal orientation, it pushes L3.36 toward the TM2-proximal position (right; gray and pink dashed lines indicate values for TRV023- and AngII-bound structures, respectively; traces are for a simulation with AngII bound, and additional simulation traces are shown in Fig. S6). RMSD is root-mean-square deviation (see Methods). (C) AngII and β-arrestin-biased ligands stabilize more inward TM6 positions in the binding pocket compared to positions favored by Gq-biased ligands (P = 0.005 for Gq-biased ligands vs. AngII; P = 0.001 for Gq-biased ligands vs. β-arrestin-biased ligands), as shown by the box plot at left (boxes extend from 25th to 75th percentile of simulation frames), because the ligand R2 residue interacts with D6.58 and D7.32 (right; dashed lines correspond to distance plotted at left). The more outward position of the extracellular portion of TM6 observed for Gq-biased ligands allows their F8 residue to adopt a horizontal orientation more frequently than that of AngII (see also Fig. S7).