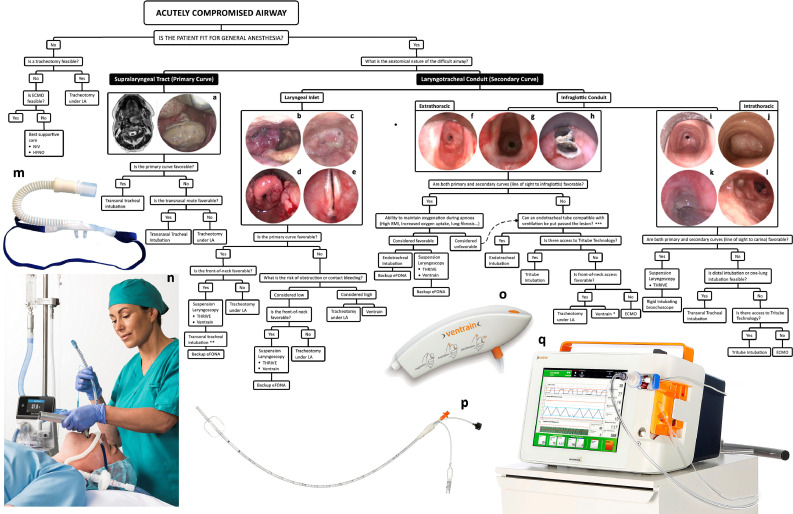

Figure 4.

A global view of managing difficult airways. The first question in any difficult airway situation is whether it is safe to undertake general anesthesia. This principally rests on hemodynamic stability and likely adequacy of oxygenation after induction of anesthesia. The question in terms of managing supralaryngeal tract pathologies is whether they can be navigated transorally or whether they need to be bypassed. The answer to this question, as with others in this decision-tree, is not absolute and is based on the experience of, and equipment available to, the team. Laryngotracheal conduit pathologies may be divided into those that obstruct and obscure the laryngeal inlet, principally oropharyngeal, supraglottic, and transglottic lesions, and those that arise below the laryngeal inlet. The standard of care for managing airway compromise due to laryngeal inlet pathology is a tracheotomy under local anesthesia, but in highly-selected proportion of these patients, they may be managed with suspension laryngoscopy and THRIVE10. Management of difficult airways due to infraglottic conduit pathologies is described in the text. (A) Case of a pedunculated tumor arising from the posterior pharyngeal wall and causing obstruction of the air column; (B) A hemangioma arising from the aryepiglottic fold and obstructing the laryngeal inlet; (C) a hypopharyngeal tumor causing severe distortion and obstruction of the laryngeal inlet; (D) laryngeal sarcoidosis; (E) airway compromise due to bilateral vocal fold immobility caused by a posterior glottic scar; (F, g) Two cases of intubation-related extrathoracic tracheal stenosis causing airway compromise; h. acute airway obstruction due to in-situ tracheal stent fracturing; (I) circatricial intrathoracic tracheal stenosis caused by tracheostomy tube cuff injury; (J) An intrathoracic tracheal tumor; (K) Acute airway obstruction caused by tracheostomy tube tip injury in a patient with long-term tracheotomy due to bilateral vocal immobility. The lesion is fully wrapped around the endotracheal tube which has been introduced through the tracheotomy stoma; (L) Complete left-sided and 60% right-sided main bronchial obstructions in a patient with a history of mediastinal lymphoma whose acute airway obstruction was treated some years previously with an uncovered metal stent. The lymphoma fully responded to oncological treatment but subsequent clinical presentation was with stent migration, fracturing, and incorporation into the distal tracheal and bronchial walls with recurrent granulation tissue formation and distal tracheal and bronchial airway obstruction; (M) Nasal high-flow cannula (OptiFlow, Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand); (N) Nasal high-flow being used for perioxygenation and intubation (images M and N were provided courtesy of Fisher and Paykel Healthcare); (O) Ventrain system; (P) The Tritube; (Q) The Evone ventilator delivering flow-controlled ventilation (images O-Q were provided courtesy of Ventinova Medical, Eindhoven, Netherlands)). LA, local anesthesia; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; HFNO, high-flow nasal oxygen; eFONA, emergency front-of-neck access; THRIVE, transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. * Use of Cricath with Ventrain (Ventinova Medical, Eindhoven, Netherlands) should be considered with caution given the risk of total outflow obstruction and barotrauma. ** The expectation with these cases will be that intubation attempts will be performed under suspension laryngoscopy and with line-of-sight instruments, but in highly selected cases the team may elect to perform translaryngeal intubation with anesthetic instruments. An example would be image b where the supraglottic hemangioma obscures but does not obstruct laryngeal inlet and the airway may be amenable to transoral or transnasal intubation. *** These procedures are expected to be performed in an awake patient receiving high-flow nasal oxygen.