Abstract

Increasing evidence indicates that youth leadership programs that hold youth as key stakeholders are successful for suicide prevention. This project served to evaluate a train-the-trainer program for youth and their supportive adults. Hawaii’s Caring Communities Initiative for Youth Suicide Prevention developed and practiced a youth leadership model to promote individual and community well-being and to decrease suicide risks. In collaboration with multiple community partners and the Hawai‘i State Department of Health, Hawaii’s Caring Communities Initiative brought together 57 youth and 17 supportive adults from around the state for the 2019 Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Conference: Hope, Help, and Healing, a 2-day, train-the-trainer workshop, consisting of games and activities centered towards education of suicide prevention methods, in early April 2019. Of the participants attending the workshop, 44 youth and 12 supportive adults completed surveys measuring knowledge about suicide prevention and local resources, and comfort level in delivering the programs. Open-ended questions were also used to assess whether key messages were conveyed. Quantitative analyses indicated the lessons helped the participants retain the information better and increased their comfort with the material. The power of youth voice was a common theme in the qualitative data, exemplified by the statement: “We can actually make a difference in our school and community.” Findings suggest that youth engagement is an important factor in preventing suicide. Interventions centered on strength-based models of youth leadership may promote healing and enhance prevention strategies to address persistent suicide disparities in minority communities by promoting their voices in the community.

Keywords: Civil engagement, Hawai‘i, suicide prevention, youth leadership programs, youth voice

Introduction

Over the last few decades, suicide death rates in Hawai‘i and the United States have significantly increased, with dramatic increases among youth.1 Youth Risk Behavior Survey findings over the last 20 years showed adolescents in Hawai‘i selfreported among the highest rates of suicide-related behaviors, including depression, suicide ideation, planning, attempts, and attempts requiring medical attention.2,3 According to the most recent survey, 1 out of 6 high school students and 1 out of 8 middle school students in Hawai‘i seriously considered suicide.4 For the last 5 years, suicide prevention was a leading concern at a statewide youth summit.

Studies indicated that programs that promote youth voice were successful in suicide prevention.5,6 Suicide prevention within the state and among youth provided the opportunity to spread education and awareness about suicide, and its impact on communities especially through the youth communities. The years between childhood and adulthood can be difficult in ways that can lead an individual to suicidal thoughts and attempts. Despite how common such thoughts and attempts are among youth, educating and training the youth to become more aware and capable of tackling such disparities allowed more opportunities for those at risk to receive help. Ultimately, the youth relied on one another because they can relate more to each other and by raising awareness towards the youth communities, the youth suicide matter can benefit. Hawaii’s youth suicide prevention programs were adapted to meet community and cultural needs, which emphasized the importance of honoring community knowledge and prioritizing relationships.7,8

This project utilized approaches that support youth as the agents of change in their communities. Further, it served to evaluate the effectiveness of interactive activities on knowledge, recognition, comfort, and behaviors in suicide prevention through a train-the-trainer program, an accumulation of 2 evidence-based suicide prevention programs, Connect Suicide Prevention and Introduction to Sources of Strength, which was held as the 2019 Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Conference: Hope, Help, and Healing. It was hypothesized that interactive activities will improve learning, increase youth involvement, and ultimately, decrease youth suicide.

Methods

Middle and high school-aged youth and their supportive adults across the state of Hawai‘i were invited to participate in the 2019 Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Conference: Hope, Help, and Healing. Notification about the workshop and conference for youth track were sent to supportive adult leaders of the Hawai‘i Youth Leadership Council for Suicide Prevention as well as each of the County Prevent Suicide Task Forces to share with youth groups that had participated in previous suicide prevention events. As a result, the majority of participants were recruited from rural and primarily Native Hawaiian communities. The University of Hawai‘i Institutional Review Board acknowledged the project as quality improvement with anonymous data; therefore, no formal approval was necessary. The principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report were followed. A draft permission form was shared with organizations for the conference describing the workshop and conference activities, including a statement that a survey would be done to get feedback on the program. This information was retained by all organizations. Some required additional paperwork for excursions and field trips. The youth attended with the permission of their parents and guardians and the supportive adults came as their chaperone.

Fifty-seven youth and 17 supportive adults from the islands of O‘ahu, Maui, Moloka‘i, Lana‘i, and the island of Hawai‘i engaged in a 2-day train-the-trainer program offered during the Youth and Supportive Adult Track at the conference. The majority of participants knew someone who had considered suicide, some had seriously considered suicide themselves, and a few had made an attempt themselves. Supportive adults were aware of this status and protections were in place to monitor youth if there was a concern. Precautions included supportive adults serving as chaperones that were aware of their youth’s needs, trained suicide prevention specialists monitoring the group for signs, and respite rooms.

Participants took part in interactive skills building activities and were given resources. Participants were trained and certified in 2 evidence-based programs, adapted for Hawai‘i, Connect Suicide Prevention and Intro to Sources of Strength. Connect Suicide Prevention training is a comprehensive, communitybased approach to train professionals and communities in suicide prevention and response.3,9–11 Trainings focused on raising awareness of risk and protective factors and warning signs for suicide, reducing stigma, and ensuring communication using safe messaging guidelines. Sources of Strength is a universal suicide prevention approach that builds on protective influences of peers in schools and community.6,12 Sources of Strength Training improved peer leaders’ adaptive norms regarding suicide, their connectedness to adults, and their school and community engagement, with the largest gains for those entering with the least adaptive norms.

The combined program used training, relationship-building, youth empowerment, and implementation of community awareness projects. Modules were broken into 15–20-minute blocks with a purposeful game, teaching and sharing component, and an interactive activity. Examples are provided in Table 1. In the morning of day 1, attendees took part in the Connect Suicide Prevention training. Prior to lunch, they were divided into 3 groups and each group was given sections to present. The groups included both youth and supportive adults. In the afternoon, the trainees were given the opportunity to rehearse and present 2 blocks to ensure fidelity and provide feedback. The trainers made comments, noting areas of strength and improvement. The same strategy was employed on day 2 for Sources of Strength. All participants successfully delivered the programs in teams. Individual skills varied. All youth were certified to present with a trained supportive adult. The program also provided opportunities to meet and connect with other youth.

Table 1.

Examples of Program Components for Youth Training

| Program | Purposeful Game to Introduce | Share | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connect | “Posts Activity”: The purpose of this game was to recognize that risks, warning signs, and support are not always easy to identify. This activity was added to augment the slides. | Some were asked to share why they think their quotes or social media posts belonged to a certain group. Some had different interpretations of the same quotes and posts as others. | Everyone was given a quote or post they had to identify as a risk, a warning sign, or positive message. |

| Sources of Strength | “Strength Poster”: The purpose of this activity was to show that people all share similar strengths and at the same time have different strengths. | The similarities in the strengths that everyone had, which included family and friends, were discussed The differences in strengths that everyone had that some can relate to, which included, canoeing, music, and friends, were also discussed. | Everyone was divided into groups. Every member had to then draw or write what, where, or who they drew their strength from during hardship. Every group came up with a group name and a way to share their poster in a creative way. |

The youth and supportive adults were asked to complete the evaluation and turn in at the registration desk, as were all participants in the conference. Workshop attendees had the right to decline participation or not answer any question that made them uncomfortable. The survey contained Likert scale statements and open-ended questions. Evaluation is standard practice for the suicide prevention conference. The statements were presented with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). The 5 open-ended questions that were asked in the survey included: “What is a key message(s) that you took away from the Connect Training,” “What is a key message(s) that you took away from the Sources of Strength training,” “What did you find most helpful?,” “ What would you change about this training?,” and “What will you do differently as a result of this training?”

All participants in the workshop were encouraged to practice what they had learned. This was not a requirement for participation in the workshop. This information was shared in thank you notes to the organizers for the conference and not systematically collected. The vast majority of supportive adults shared the ways that their groups applied their training in May 2019.

Descriptive analyses (frequencies and cross-tabulations) and comparative (χ2 and Fisher Exact Test) were conducted to measure knowledge about suicide prevention, and comfort level with delivering each program using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp: Armonk, NY). Qualitative data were analyzed by hand. The qualitative themes reached saturation with youth and supportive adults providing consistent comments on messaging and value of the training.

Results

Surveys were received from 44 youth and 12 supportive adults, for an overall response rate of 80% and 71%, respectively. The sample description appears in Table 1. The majority of youth respondents (64%) were from O‘ahu, consistent with participation in the youth track. Three-quarters of youth respondents were members of a youth suicide prevention group and nearly all respondents (98% of youth and 100% of supportive adults) had tried to help a friend or someone else that they thought might hurt themselves. Most of youth respondents (70%) had previously attended a suicide prevention training.

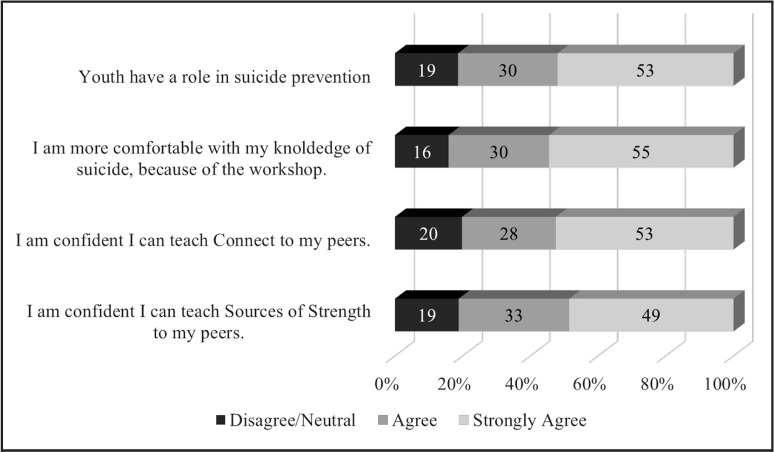

Youth and supportive adults reported increasing their knowledge and competence to prevent suicide in their own communities through the survey questions and in their feedback that was given after the conference concluded. There were no statistical differences between youth and supportive adults on any of the questions so the data were combined. The vast majority of respondents correctly answered questions related to knowledge including recognizing anger and hostility as signs of depression (96%), youth frequently tell someone of their plan to attempt suicide in advance (92%), and that asking about suicide will not encourage someone to act (98%). As illustrated in Figure 1, 83% of combined youth and supportive adult respondents indicated that youth have a role in suicide prevention. More than 81% of respondents felt they could teach Connect Suicide Prevention and Sources of Strength programs.

Figure 1.

Combined Youth and Supportive Adult Trainee Comfort and Confidence in Conducting Suicide Prevention Programs.

Key messaging for the suicide prevention programs were completely saturated. The key message of recognizing and connecting were indicated in all responses for the Connect Training program in some form. Some attendees highlighted recognizing signs, especially subtle changes, and others highlighted connecting to their friends or family members. The key message of strength was identified in all responses for the Sources of Strength program. Respondents either specified the wheel of strengths or described the need to identify their strengths, serving as a source for others, and looking to others to be a source of strength. Three themes emerged from the open-ended questions on value of the training (helpful, and do differently). The power of youth voice was the most common theme with 86% of youth and 100% of the supportive adults sharing that youth can lead and be empowered to prevent suicide in their communities. One youth wrote, “We can actually make a difference in our school and community.” Another stated “Suicide prevention is everyone’s responsibility. I can be there for a person feeling like suicide.” Another youth stated, “I know how to react better to certain situations, how to teach this info, and how to provide support.” This was reinforced by statements from supportive adults such as, “Youth can do this. We need to allow them to lead.” and “We need to make opportunities for youth to share this program on [my island].” The second theme that emerged was the importance of focusing on strengths. This was repeated from the key messages on Sources of Strength with 68% of youth and 33% of supportive adults adding comments about focusing on strengths. One youth stated, “There are strengths everywhere. Sharing about your sources of strength and support is important in a person’s well-being.” A supportive adult commented, “We need to spend more time focusing on strengths” The final common theme was the role the activities played in training, indicated by 52% of youth and 42% of supportive adults. For example, one youth commented, “I loved the games and activities. They made it easier for me to come out of my shell and step up to lead.” This was reinforced by the supportive adults as demonstrated by one of their comments, “The game-share-activity style was so engaging, fun, and made for a quick impactful training.” Interesting, in the closing exercise for the training, nearly all participants specified the game activities or the opportunity to meet others as their favorite part of the conference.

Besides learning how to navigate others in suicide prevention, an additional hope of the conference was to have the trained youth and supportive adults teach and train others around them in the same way they were trained. In May 2019, youth from Moloka‘i, Maui, and the Leeward Coast of O‘ahu reportedly held sessions for their peers or teachers in suicide prevention. In less than 1 month, more than 150 additional youth and supportive adults have been trained by youth attending the youth track at the conference. Interventions centered on strength-based models of youth leadership may promote healing and enhance prevention strategies to address suicide by promoting their voices in the community.

Discussion

Youth suicide is an important and serious, yet preventable, community and societal issue. Interventions centered on strength-based models of youth leadership may promote healing and enhance prevention strategies to address persistent health disparities in minority communities by promoting their voices in the community. The power of youth voice was a common theme. The findings suggest that positive youth development is crucial in preventing suicide. Ongoing efforts to promote and sustain youth voice, youth training, and suicide prevention are needed. Overall, this study strengthens existing literature about the beneficial effects of programs grounded in positive youth development.13 Previous research shows that those who participated in youth development programs have refined their leadership and civic engagement skills, as well as their ability to make healthy decisions.14 Challenging youth to enhance their strengths require community investment. Youth want to be empowered to prevent suicide in their communities.

Given many participants were either involved in existing suicide prevention groups or were interested in creating such a group, they may not have been representative of the population of students in Hawai‘i. Similar studies that include more communities are needed to determine if there are differences in program effectiveness. Student interest may have influenced the positive findings, including the high rates of knowledge, as well as their comfort and confidence with the material. Additionally, the majority of people who attended the conference agreed to evaluate the conference, though not every person turned in their survey. One community group was missing entirely, inadvertently misplacing their surveys. Therefore, this sample may not be representative of all conference attendees. Despite these limitations, this is the first time a peer train-the-trainer program of this magnitude relating to suicide prevention has been done in Hawai‘i, and enthusiasm is being generated for future activities.

These results also have practical implications for youth suicide prevention programs on regional and national levels. Since suicide is a public health problem that is generally preventable, it is crucial to make evidence-based interventions available. The data from this study indicated that the use of interactive activities in these programs is one way to unite youth and adults who want to assist those considering suicide. In order for these programs and groups to continue, it is important to make training for supportive adults available and generate the necessary funding to sustain community work.

Table 2.

Sample Description Train-the-Trainer Respondents

| Descriptors | Youth (N=44) n (%) |

Supportive adult (N=12) n (%) |

Statisticsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | X2=1.84, df=2, P=.15 | ||

| Male | 14 (32%) | 2 (17%) | |

| Female | 28 (64%) | 10 (83%) | |

| Otherb | 2 (4%) | 0 | |

| Island | Fisher Exact Test P=.15 | ||

| O‘ahu | 28 (64%) | 5 (42%) | |

| Neighbor islandc | 16 (36%) | 7 (58%) | |

| Helped a friend | 43 (98%) | 12 (100%) | Fisher Exact Test P=.79 |

| Attended previous, suicide prevention training | 30 (68%) | 7 (58%) | Fisher Exact Test P=.38 |

X2 and the Fisher Exact Test were used to test relationships between participant type (youth, supportive adult) and categorical data. The Fisher Exact Test was used to when expected frequencies were fewer than five.

Participants who do not identify with their sex assigned at birth.

O‘ahu is the most populated and hosted the conference in 2019. Neighbor islands refer to the less populated islands in the state of Hawai‘i including Hawai‘i Island, Lana‘i, Maui, and Moloka‘i. There were no participants from Kaua‘i.

Acknowledgements

Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Youth Track Planning Committee: Malia Agustin, Blane Garcia, Jennifer Lyman, Sunny Mah, and Dave Rehuher. Their positive energy and desire to change the lives of youth was inspiring by being role models. Funded in part by funded in part by the Hawai‘i State Department of Health, University of Hawaii’s School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Ola HAWAII (U54 MD007601 Research Centers in Minority Institutions Program), Mental Health America of Hawai‘i, and Prevent Suicide Maui Task Force.

Appreciation to the Youth Leadership Council who were inspirations by their voices and power to prevent suicide.

Conflict of Interest

The authors identify no conflict of interest.

Disclosure Statement

This paper was presented, in part, at the Biomedical Sciences and Health Disparities Symposium on April 25, 2019 and received the first place winner in the John A. Burns School of Medicine Undergraduate Division.

References

- 1.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;241:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subica AM, Wu LT. Substance use and suicide in Pacific Islander, American Indian, and multiracial youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;54((6)):795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong SS, Sugimoto-Matsuda JJ, Chang JY, Hishinuma ES. Ethnic differences in risk factors for suicide among American high school students, 1999-2009: The vulnerability of multiracial and Pacific Islander adolescents. Arch in Suicide Research. 2012;16:159–173. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawaii's Indicator Based Information System. Monitoring Hawaii's Health. http://ibis.hhdw.org/ibisph-view/query/selection/yrbs/_YRBSSelection.html. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- 5.Chung-Do J, Goebert DA, Bifulco K, et al. Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative: Mobilizing rural and minority communities for youth suicide prevention. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2015;8((4)):108–123. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyman PA, Brown CH, LoMurray M, Schmeelk-Cone K, Petrova M. An outcome evaluation of the sources of strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100((9)):1653–1861. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung-Do J, Bifulco K, Antonio M, Tydingco T, Helm S, Goebert D. Cultural analysis of the NAMI-NH Connect Suicide Prevention Program by rural community leaders in Hawai‘i. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2016;40((2)):87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goebert D, Alvarez A, Andrade NN, Balberde-Kamalii J, Carlton BS, Chock S, Chung-Do JJ, Eckert MD, Hooper K, Kaninau-Santos K, and Kaulukukui G. Hope, help, and healing: Culturally embedded approaches to suicide prevention, intervention and postvention services with native Hawaiian youth. Psychological services. 2018;15((3)):332–339. doi: 10.1037/ser0000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baber K, Bean G. Frameworks: A community-based approach to preventing youth suicide. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37((6)):684–696. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bean G, Baber KM. Connect: An effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide and Life-Threatening behavior. 2011;41((1)):87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suicide Prevention Resource Center Best Practice Registry Section III: Adherence to Standards. Connect/Frameworks Suicide Prevention Program. http://www2.sprc.org/sites/sprc.org/files/ConnectFrameworksPrevention.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2019.

- 12.LoMurray M. Bismarck, ND: The North Dakota Suicide Prevention Project; 2005. Sources of Strength facilitators guide: Suicide prevention peer gatekeeper training. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer JB, Erbacher TA, Rosen P. School-based suicide prevention: A framework for evidencebased practice. School Mental Health. 2018;11(54):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9245-8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerner RM, Lerner JV. Chevy Chase, MD: National 4-H Council; 2013. The positive development of youth: Comprehensive findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. [Google Scholar]