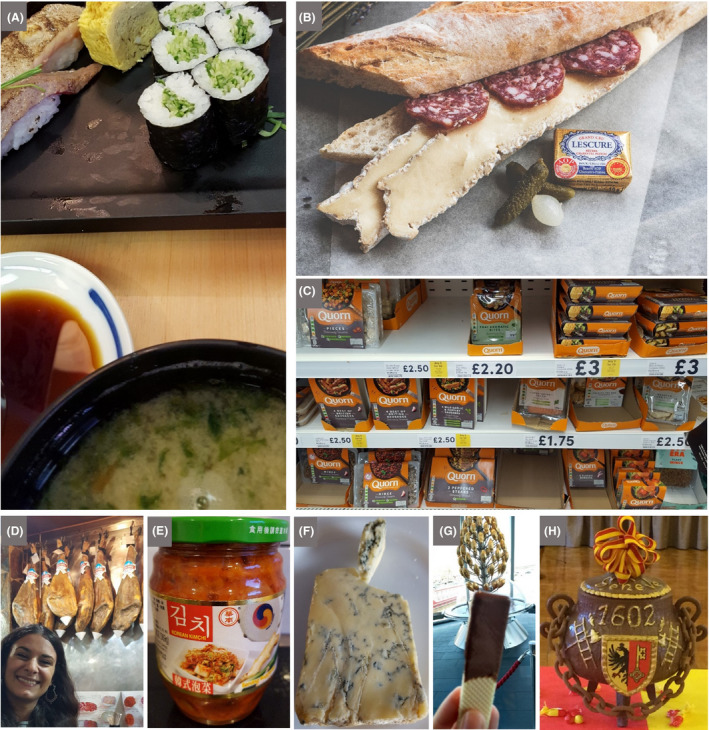

Fig. 4.

A trip to the food store or a meal can become an adventure of microbiological discovery

A. Breakfast at Tsukiji Market, Japan. The miso in miso soup is a traditional Japanese paste produced by fermenting salted soya beans with kōji, which is also made by fermentation of rice or barley with the fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Soy sauce is made by fermenting salted soya beans and wheat by a complex community of hydrolytic fungi and bacteria, as well as lactic acid bacteria. Sushi rice is prepared with a sweet rice wine vinegar (mirin) to give it a delicate, sweet but sharp flavour. Vinegar can be prepared from almost any sugary solution by an alcoholic fermentation followed by an acetic fermentation. In Japan, vinegar traditionally derives from rice and kōji‐fermented rice.

B. Salami and Brie baguette with pickles. Nearly all the foods in this image require microbes for their production: Bakers’ yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) makes the dough rise for the bread; Penicillium species and lactic acid bacteria are among the microbes involved in both salami and Brie production; acetic acid‐producing bacteria make the vinegar from alcoholic drinks for the pickles.

C. The drive towards reducing meat in the diet has opened a market for a range of meat‐free products, leading to a resurgence in the sales of Quorn, which is made from filamentous mycelium of the soil fungus Fusarium venenatum.

D. Dry‐cured hams in a bar in Salamanca, Spain. Spanish ham is traditionally cured in brine with sea salt, often with added sodium nitrate, to lower the water activity to an extent that prevents the growth of spoilage organisms.

E. Kimchi, a staple food in Korea, is becoming popular worldwide. Cabbage, along with numerous variations of vegetables and spices, is salted and undergoes fermentation dominated by lactic acid bacteria. The health benefits of this tangy, salty and often spicy product are widely reported (Tamang et al., 2016).

F. Stilton cheese, which, in addition to requiring lactic acid bacteria and other microbes in its manufacture, is inoculated with Penicillium roqueforti to produce the blue veins that contribute to the distinctive flavour.

G. Chocolate from the Lindt factory in Cologne, Germany – an enjoyable way to learn about the history and microbiology of chocolate.

H. Chocolate is moulded into a multitude of artistic forms that titillate the senses, especially of children. The example shown is that of the Geneva ‘marmite’, a chocolate representation of a soup cauldron containing marzipan vegetables, made each year for the festival of ‘Escalade’, the celebration of the defeat of an assault on the city in 1602. Legend has it that an old lady (Catherine Cheynel or Mère Royaume), who was making vegetable soup at night, spotted the attackers who were scaling the city walls, sounded the alarm and threw the hot soup cauldron at them. Incidentally, Marmite – the yeast extract spread putatively developed by a German scientist, Justus von Liebig, using leftover yeast from the brewing of beer in Burton upon Trent, UK – derives from the French name ‘marmite’, as it is sold in pots with a similar shape to the cauldron. Photographs A and C‐F by Terry McGenity, B by Jez Timms on Unsplash, G by Mairi McGenity and H by Kenneth Timmis.