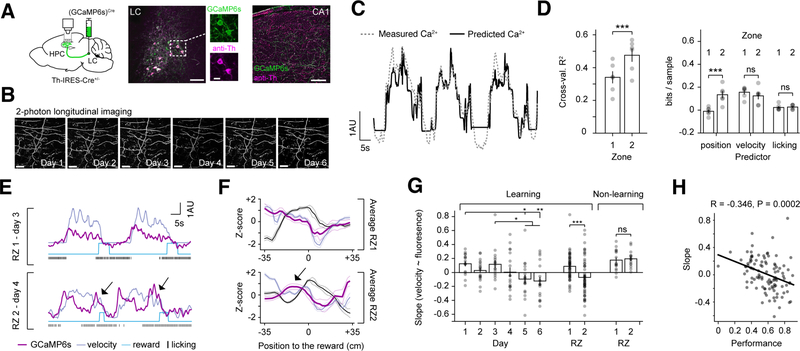

Figure 2. Locus coeruleus activity changes during GOL.

A. Left: LC-CA1 axon labeling strategy. Cre-dependent virus [rAAV2/9:EF1a-(GCaMP6s)Cre] was injected into the locus coeruleus (LC) of Th-IRES-Cre+/− mice. LC axons in hippocampal (HPC) CA1 were imaged through a cannula. Middle and right: post hoc immunofluorescent staining with antibodies against tyrosine-hydroxylase (anti-Th) and GCaMP (anti-GFP) in LC and HPC to confirm labeling strategy. Scale bar: LC: 50 μm; inset: 20μm, HPC: 100 μm.

B. Example of multi-day 2p imaging of LC-CA1 axons in CA1 stratum oriens (SO). Scale bar: 50 μm.

C. A generalized linear model (GLM) trained with three covariates (position, velocity, and licking) to predict LC-CA1 activity. Example trace of LC-CA1 calcium activity (dashed line) and predicted by the GLM (solid line).

D. Left: cross-validated R2 calculated on the held out test data in RZ1 sessions and RZ2 sessions (mean±SEM, RZ1: 0.34±0.04; RZ2: 0.48±0.04; n=6 mice, two-tailed paired t-test, t(5)=−5.97, p=0.004). Right: contribution of different variables estimated by the amount of information gained by including each variable during RZ1 and RZ2 (mean±SEM; position in RZ1: −0.01±0.013; position in RZ2: 0.14±0.03; velocity in RZ1: 0.15±0.03; velocity in RZ2: 0.12±0.03; licking in RZ1: 0.02±0.01; licking in RZ2: 0.03±0.01; n=6 mice, two-tailed paired t-tests between RZ1 and RZ2 for: velocity, t(5)=−4.84, p=0.005; position, t(5)=1.49, p=0.196; licking, t(5)=−0.63, p=0.556).

E. Example traces of LC-CA1 activity (dark magenta) and behavioral variables in RZ1 and RZ2 for 2 consecutive laps. In RZ1, axons are correlated with velocity, while in RZ2, there is a decorrelation between LC-CA1 activity and velocity (arrows). 1 arbitrary unit (AU) refers to 1 sigma of the Z-score trace for the fluorescence F (GCaMP6s), and speed in cm/s (velocity).

F. Average peri-stimulus activity histogram of the LC-CA1 signal (dark magenta), velocity (lavender) and licking (black) in RZ1 and RZ2, centered around reward. The overshoot in LC-CA1 activity is only visible in RZ2 (arrow) (n=6 mice, mean: darker colors, SEM: lighter colors). It preceded the reward by an average of 24.33±2.02 cm.

G. Slope of the linear fit between velocity and LC-CA1 signals. The signals are less correlated over the course of learning. Data are in mean±SEM for sessions in a given day collected from n=6 mice (Learning day1: 0.126±0.038; day2: 0.03±0.036; day3: 0.118±0.056; day4: 0.006±0.067; day5:−0.093±0.061; day6:−0.121±0.059. One-way mixed-effects model ANOVA F(5, 82)=4.28, p=0.0017. Post-hoc Tukey test, day1 vs. day5, p=0.026. day1 vs. day6, p=0.008. day2 vs. day5, p=0.047. day2 vs. day6, p=0.016), and are correlated in RZ1 but decorrelated in RZ2 (Learning RZ1: 0.09±0.026; RZ2: −0.069±0.036. Two-tailed unpaired t-test, n1=51 sessions, n2=54 sessions, t(104)=−3.57, p=0.0005). Two mice that did not learn the task showed signals correlated with velocity in both RZs (Non-learning RZ1: 0.175±0.037, RZ2: 0.194±0.03. Two-tailed unpaired t-test, n1=15 sessions, n2=16 sessions, t(30)=0.399, p=0.693).

H. The slope of the relationship between speed and fluorescence was correlated with behavioral performance, as measured by the fraction of licks in the RZ (Pearson’s R test, n=105 points, R=−0.346, p=0.0002). Each point is the average performance as a function of the average correlation coefficient for each session, and each mouse.

See also Figures S1–4.