Abstract

Multiple myeloma is a malignant plasma-cell disease, which is highly dependent on the hypoxic bone marrow microenvironment. However, the underlying mechanisms of hypoxia contributing to myeloma genesis are not fully understood. Here, we show that long non-coding RNA DARS-AS1 in myeloma is directly upregulated by hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1. Importantly, DARS-AS1 is required for the survival and tumorigenesis of myeloma cells both in vitro and in vivo. DARS-AS1 exerts its function by binding RNA-binding motif protein 39 (RBM39), which impedes the interaction between RBM39 and its E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF147, and prevents RBM39 from degradation. The overexpression of RBM39 observed in myeloma cells is associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, knockdown of DARS-AS1 inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway, an effect that is reversed by RBM39 overexpression. We reveal that a novel HIF-1/DARS-AS1/RBM39 pathway is implicated in the pathogenesis of myeloma. Targeting DARS-AS1/RBM39 may, therefore, represent a novel strategy to combat myeloma.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by abnormal accumulation of monoclonal plasma cells in the bone marrow and broad clinical and pathophysiological heterogeneity leading to a fatal outcome. Hypoxia in specific bone marrow niches induces numerous changes in the expression of genes that contribute to the maintenance of myeloma cells and the progression of myeloma, leading to drug resistance and cancer recurrence.1 Focusing on the hypoxia-related pathogenic mechanisms in myeloma may facilitate the optimization of the choice of therapeutic regimen and improve clinical outcomes.

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) are mRNA-like transcripts that are longer than 200 nucleotides.2,3 Accumulating evidence indicates that lncRNA are crucial molecules that participate in gene regulation at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels.3,4 Aberrant expression of lncRNA can promote the development and progression of malignant tumors through contributing to proliferation, invasion and metastasis.5–7 lncRNA may, therefoe, serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancers. However, few lncRNA have been functionally studied in MM. Many hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-dependent protein-coding genes contribute to adaptation to hypoxia. Whether lncRNA are involved in the response to hypoxia in myeloma and the determination of their regulatory roles is important for a better understanding of the development and progression of myeloma.

RNA-binding motif protein 39 (RBM39) is a transcriptional coactivator for the steroid nuclear receptors ESR1/ER-α and ESR2/ER-β as well as for JUN/AP-1 and NF-κB. RBM39 is also involved in the pre-mRNA splicing process.8–11 Previous studies have pinpointed RBM39 as a proto-oncogene with important roles in the development and progression of numerous types of malignancies.8,12,13 However, the role of RBM39 in MM is largely unknown.

By analysis of high-throughput RNA sequencing results, we identified that lncRNA DARS-AS1 was significantly upregulated in myeloma cells under hypoxic conditions. We evaluated its biological role and clinical significance in tumor progression and revealed that the novel HIF-1/DARS-AS1/RBM39 signaling pathway is implicated in the tumorigenesis of MM.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

RPMI 8226, LP-1, U266, H929, and HEK293T cells were obtained from the Cell Resource Center of Shanghai Institute for Biological Science, Chinese Academy of Science. All the cell lines have been authenticated using short tandem repeat genotype detection. Myeloma cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, CA, USA) containing 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). The hypoxic environment (1% O2) was generated by flushing a 94% N2/5% CO2 mixture into the incubator. Retroviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells by transient co-transfection of target gene expression vectors, Gag-pol, and VSVG packaging plasmid, while lentiviral particles were produced by transient co-transfection of target gene expression vectors, psPAX2 and pMD2.G packaging plasmid, using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were infected in culture medium supplemented with polybrene (8 μg/mL) and 24 h later the medium was changed to RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was received from the relevant ethics committees.

Luciferase assay

For DARS-AS1 promoter luciferase reporter assays, luciferase reporter constructs (100 ng) containing the potential HIF response element (HRE) sequence [wildtype, (WT) or mutant (MUT)], together with pSV40-renilla (10 ng), and HIF-1α overexpression plasmids (800 ng) were transfected into HEK293T cells in 24-well plates. Luciferase activity assays were performed 48 h after transfection (Promega, Madison, USA). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to the corresponding renilla luciferase activity by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System. All experiments were performed three times.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Corresponding antibody or IgG was added to cell lysate that was treated with A+G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The mixture was rotated for 6 h and precipitated beads were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing a protease inhibitor cocktail.

RNA immunoprecipitation

RNA immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using a Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatants were incubated with 1-2 μg of anti-Flag (Sigma, MO, USA) or mouse IgG (Invitrogen, MA, USA) for 6 h at 4°C followed by precipitation with protein A/G agarose (Pierce, Rockforld, IL, USA). The co-precipitated RNA were detected by quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR).

RNA pulldown and mass spectrometry analysis

Full-length DARS-AS1 were constructed by subcloning the gene sequences into a pcDNA3.1 (+) backbone. Biotin-labeled DARS-AS1 was synthesized using Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche; Basel, Switzerland) by T7 RNA polymerase (Promega; WI, USA), treated with RNase-free DNase I (Promega) and purified with an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Thirty micrograms of biotinylated RNA were used in each pulldown assay. The proteins with biotin-labeled DARS-AS1 were pulled down with streptavidin magnetic beads (Thermo, Fisher SCientific, MA, USA) after incubation overnight. The samples were separated by electrophoresis and the specific bands were identified using mass spectrometry and a human proteomic library.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells with HIF-1α overexpression (2×107) were harvested and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using a SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Agarose Beads) (CST, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used are listed in Online Supplementary Table S3.

Bioinformatics analysis

Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/) was used to analyze the protein-protein interactions.

Statistics

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE). For comparisons of two groups, a t-test was used. When comparing more than two groups, analysis of variance with the Tukey test for multiple comparisons was used. Statistical significance is defined as: *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Results

DARS-AS1 is upregulated under hypoxia in myeloma cells

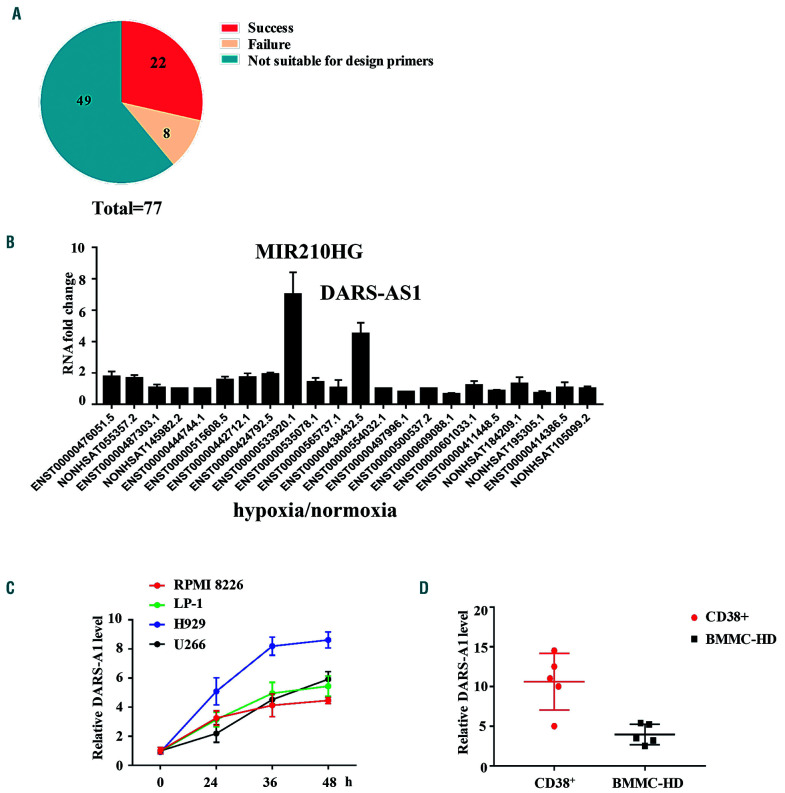

To identify hypoxia-regulated lncRNA, we analyzed the difference in the RNA-sequencing data of U266 cells in normoxic and hypoxic culture environments (Online Supplementary Table S4). Twenty-two upregulated lncRNA in U266 cells were successfully identified (Figure 1A). Q-PCR revealed that two lncRNA, DARS-AS1 and MIR210HG, were significantly upregulated under the hypoxic condition (Figure 1B). The modulation of MIR210HG did not have significant effects on myeloma cell proliferation or apoptosis (Online Supplementary Figure S1A-D). Thus, we mainly studied the function of DARS-AS1 in myeloma.

Figure 1.

DARS-AS1 is upregulated in myeloma cells in a hypoxic environment. (A) RNA-sequencing analysis revealed 77 differentially expressed long non-coding (lnc)RNA between myeloma cells cultured in normoxic or hypoxic conditions. (B) Twenty-two upregulated lncRNA in U266 cells were successfully identified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR). (C) Multiple myeloma cell lines were cultured under hypoxic culture conditions (1% oxygen concentration) for 48 h and DARS-AS1 expression levels were determined by Q-PCR and normalized to those of 18S rRNA. (D) CD38+ cells derived from bone marrow of patients with active myeloma and normal human bone marrow mononuclear cells were cultured in a hypoxic environment (1% oxygen concentration) for 24 h. The DARS-AS1 expression levels were determined by Q-PCR and normalized to those of 18S rRNA. BMMC-HD: bone marrow mononuclear cells from healthy donors.

First, we assessed the expression of DARS-AS1 in myeloma cell lines. We found that the hypoxic environment (1% oxygen concentration) caused a significant increase in the level of expression of DARS-AS1 in the MM cell lines (Figure 1C). The expression of DARS-AS1 in CD38+ cells derived from bone marrow of patients with active myeloma was significantly higher than that of normal human bone marrow mononuclear cells after culture in a hypoxic environment for 24 h (Figure 1D). These data suggest that hypoxia leads to upregulation of DARS-AS1.

DARS-AS1 participates in the proliferation of myeloma cells, inhibits their apoptosis and accelerates tumorigenesis

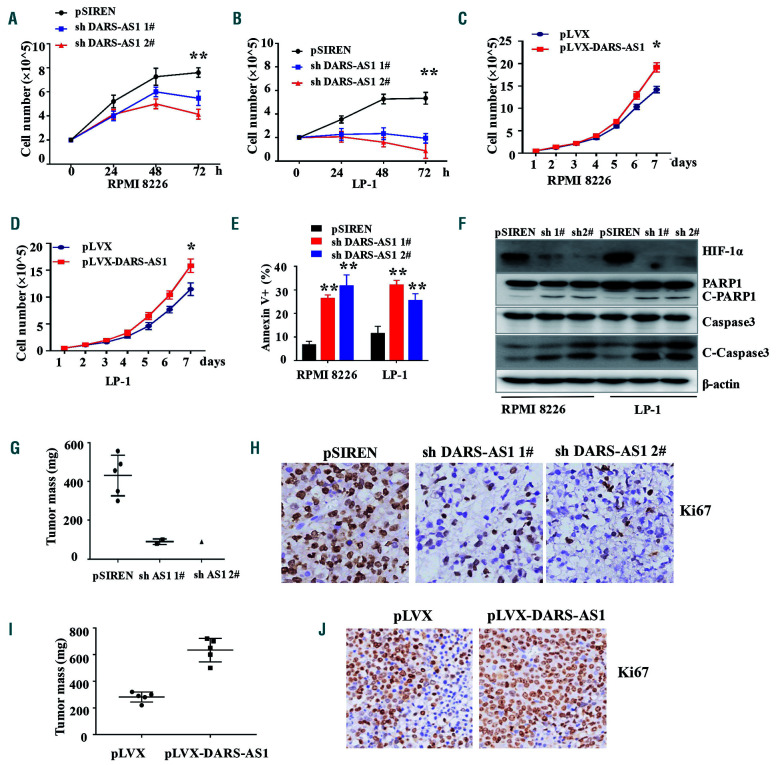

We next investigated the role of DARS-AS1 in myeloma cells. Importantly, we found that the expression of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against DARS-AS1 in the MM cell lines RPMI 8226 and LP-1 substantially inhibited cell proliferation in the hypoxic environment (Figure 2A, B, Online Supplementary Figure S2A), whereas the overexpression of DARS-AS1 promoted cell proliferation (Figure 2C, D, Online Supplementary Figure S2B). Furthermore, the knockdown of DARS-AS1 resulted in a substantial increase in the percentages of apoptotic cells in the hypoxic environment (Figure 2E), and DARS-AS1 overexpression reduced the rate of apoptosis of cells starved of glucose (glucose 1 mM) (Online Supplementary Figure S2C), as evidenced by both the increased annexin V+ cell population and the cleavage of caspase-3/PARP1 (Figure 2F, Online Supplementary Figure S2D, E). At the same time, DARS-AS1 overexpression attenuated the sensitivity of myeloma cells to bortezomib (2.5 nM) (Online Supplementary Figure S2F). However, knockdown of DARS-AS1 did not have significant effects on cell migration (Online Supplementary Figure S2G), invasion (Online Supplementary Figure S2H) or cell-cycle distribution (Online Supplementary Figure S3A-C) of myeloma cells in the hypoxic environment. Next, we injected RPMI 8226 cells with stable knockdown/overexpression of DARS-AS1 into the back flank of NOD-SCID mice. We found that stable knockdown of DARS-AS1 in RPMI 8226 cells remarkably inhibited the tumorigenesis of these cells in vivo, whereas overexpression of DARS-AS1 significantly enhanced tumor growth (Figure 2G, I, Online Supplementary Figure S3D). Ki67 and TUNEL staining of xenografts further confirmed these findings (Figure 2H, J, Online Supplementary Figure S3F). These results indicate that DARS-AS1 promotes MM cell growth and survival, and inhibits apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2.

DARS-AS1 participates in proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of myeloma cells in a hypoxic environment. (A, B) Cell growth of RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells with DARS-AS1 knockdown in a hypoxic environment was determined every 24 h for 72 h using an automated cell counter (Countstar). (C, D) Cell growth of RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells with DARS-AS1 overexpression was determined every day for 7 days using an automated cell counter (Countstar). (E) The rates of annexin V+ cells in myeloma cells with DARS-AS1 knockdown and control cells were determined by flow cytometry. (F) Cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP were demonstrated by western blotting of RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells with DARS-AS1 knockdown. (G, I) Xenograft mouse models of myeloma cells with DARS-AS1 overexpression or DARS-AS1 knockdown in NOD-SCID mice. (H, J) Ki67 staining of xenografts of DARS-AS1 overexpressing or DARS-AS1 knockdown cells.*P<0.05 and **P<0.01, compared with the control. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean from three experiments.

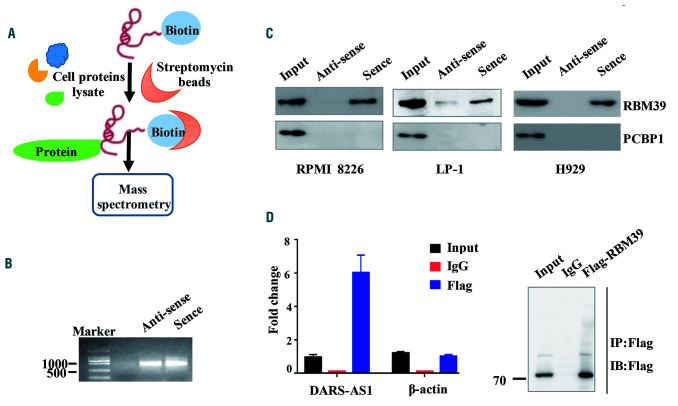

Identification of DARS-AS1-interacting proteins

Recent studies have uncovered the involvement of many lncRNA in signal transduction regulation through their interactions with proteins.14,15 To explore the molecular mechanism by which DARS-AS1 exerts its effects on MM cells, we performed biotin-labeled RNA pulldown, followed by mass spectrometry assays to identify the DARS-AS1-interacting proteins in RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells (Figure 3A, B). After exclusion of the non-specifically binding proteins present in both the sense and antisense of DARS-AS1 precipitate, six potential target proteins were identified, among which RBM39 and PCBP1 were of predominant interest (Online Supplementary Figure S5A). Only RBM39 binding with DARS-AS1 in three myeloma cell lines was detected by western blotting in three independent RNA pulldown assays (Figure 3C). The specific interaction between DARS-AS1 and RBM39 was also confirmed by an RNA immunoprecipitation assay. Plasmid-overexpressing RBM39 with a Flag-tag was transferred into HEK293T cells and then cultured in the hypoxic environment for 24 h. We observed DARS-AS1 enrichment (but not actin mRNA enrichment) using the Flag antibody compared with a nonspecific antibody (IgG control) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

DARS-AS1 interacts with RBM39. (A) Schematic of the RNA DARS-AS1 pulldown experiment. (B) RNA electrophoresis showed the sense and antisense DARS-AS1 in vitro.(C) Western blotting analysis of the proteins from the proteomics screen after pulldown. (D) RNA immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using a Flag antibody (exogenous RBM39 protein with Flag-tag), and specific primers to detect DARS-AS1 or β-actin.

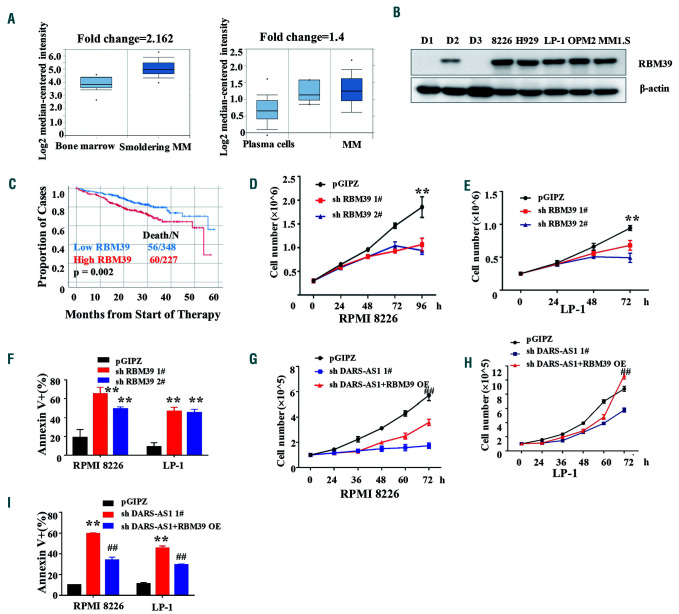

RBM39 promotes myeloma cell proliferation and inhibits cell apoptosis in the hypoxic environment

According to the Oncomine database, the transcription levels of RBM39 were significantly higher in patients with smoldering myeloma (n=12) than those of bone marrow mononuclear cells from healthy donors (n=22) (P<10-4). Data from another 74 myeloma patients also led to an identical conclusion (Figure 4A). Consistently with the aforementioned results, RBM39 was more highly expressed in the tested myeloma cell lines (Figure 4B). Importantly, patients with high expression of RBM39 had a poor response to treatment (Figure 4C). To further elucidate the biological functions of RBM39 in MM cells, we stably knocked down RBM39 using two independent shRNA in MM cells. The downregulation of RBM39 significantly inhibited MM cell growth and survival, and induced apoptosis (Figure 4D-F) under the hypoxic environment. Of note, cell apoptosis and the inhibition of MM cell proliferation that resulted from the downregulation of DARS-AS1 were partially reversed by the overexpression of RBM39 in the hypoxic environment (Figure 4G-I). These results indicate that RBM39 may mediate the biological functions of DARS-AS1 in MM in a hypoxic environment.

Figure 4.

Role of RBM39 in myeloma cells under hypoxia. (A) Oncomine data showing the mRNA levels of RBM39 in myeloma cells and plasma cells. (B) Western blotting analysis of RBM39 in myeloma cell lines and mononuclear cells from healthy donors. D1/D2/D3: healthy donor 1/2/3. (C) Data from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF) showing the survival rate after treatment in patients with high/lower expression of RBM39. (D, E) Numbers of myeloma cells transfected with short hairpin (sh)RNA targeting RBM39 were determined by an automated cell counter (Countstar). **P<0.01, compared with the control. (F) Annexin V+ cells in RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells transfected with shRNA targeting RBM39 or control shRNA were assessed using flow cytometry. **P<0.01, compared with the control. (G, H) The growth of RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells under hypoxia was assessed by an automated cell counter (Countstar). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) (n=3). shDARS-AS1: DARS-AS1 was knocked down in myeloma cells. shDARS-AS1+RBM39 overexpression (OE): DARS-AS1 was knocked down and then RBM39 overexpressed in myeloma cells. ##P<0.01, shDARS-AS1+RBM39 OE compared with the shDARS-AS1. (I) Cell apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometry analysis. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n=3). shDARS-AS1: DARS-AS1 was knocked down in myeloma cells. shDARS-AS1+RBM39 OE: DARS-AS1 was knocked down and then RBM39 overexpressed in myeloma cells. **P<0.01, compared with the control. ##P<0.01, shDARS-AS1+RBM39 OE compared with shDARS-AS1.

DARS-AS1 regulates mammalian target of rapamycin signaling via RBM39 under the hypoxic environment

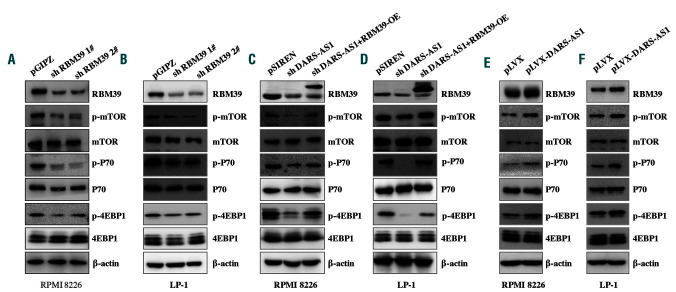

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway plays critical roles in regulating myeloma cell proliferation and apoptosis. Previous reports suggested that RBM39 might be involved in these pathways.16 We, therefore, investigated the impact of RBM39 silencing on the mTOR signaling pathway. Knockdown of RBM39 resulted in a substantial decrease in p-mTOR, p-4EBP1, and p-P70 levels in the hypoxic environment compared to the levels in control cells (Figure 5A, B). Similar results were obtained in DARS-AS1-silenced cells. It is worth noting that the inhibition of mTOR signaling that resulted from DARS-AS1 knockdown was rescued by overexpression of RBM39 (Figure 5C, D), which suggests that the effects of DARS-AS1 are mediated mainly by RBM39. Our hypothesis was further supported by the increase of p-mTOR, p-4EBP1, p-P70 and RBM39 levels (Figure 5E, F) after DARS-AS1 overexpression in myeloma cells.

Figure 5.

DARS-AS1 regulates the RBM39-related signaling pathway in hypoxic conditions. (A, B) Immunoblot analysis of total and phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and downstream pathway proteins in RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells expressing RBM39 short hairpin (sh)RNA or control shRNA. (C, D) mTOR signaling was analyzed in RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells with DARS-AS1 silencing or DARS-AS1 silencing and RBM39 overexpression (OE). (E, F) mTOR signaling was analyzed in RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells with DARS-AS1 OE.

DARS-AS1 inhibits RBM39 degradation in the hypoxic environment

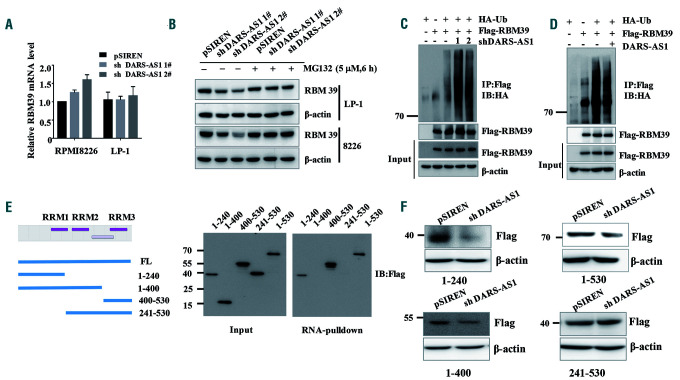

To further understand the mechanism of regulation between RBM39 and DARS-AS1, we stably downregulated DARS-AS1 and RBM39 in MM cells. The downregulation of the RBM39 protein did not affect the level of DARS-AS1 in either RPMI 8226 or LP-1 cells in the hypoxic environment (Online Supplementary Figure S5B,C). Intriguingly, the knockdown of DARS-AS1 caused downregulation of the level of RBM39 protein without decreasing the level of mRNA in both RPMI 8226 and LP-1 cells in the hypoxic environment (Figure 6A). However, the change in the RBM39 protein level was abolished by the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 6B), suggesting that DARS-AS1 may regulate the degradation of RBM39 in hypoxia. We also treated the DARS-AS1-knockdown and control MM cells with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. As shown in Online Supplementary Figure S5D, the degradation rate of RBM39 was significantly accelerated in DARS-AS1 knockdown myeloma cells in a hypoxic environment. Moreover, the knockdown of DARS-AS1 increased the ubiquitination of RBM39 in hypoxia (Figure 6C). In contrast, the overexpression of DARS-AS1 reduced the ubiquitination of RBM39 (Figure 6D). These findings indicate that DARS-AS1 regulates the stability of RBM39 via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in a hypoxic environment.

Figure 6.

DARS-AS1 interacts with and inhibits RBM39 degradation in a hypoxic environment. (A) Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis of RBM39 mRNA (mean ± standard deviation) in DARS-AS1 knockdown cells in a hypoxic environment. (B) DARS-AS1-silenced myeloma cells were treated with dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO, 1:1000) or MG-132 (5 μM) for 6 h under hypoxic conditions. (C) HEK293T cells overexpressing Flag-RBM39 only, overexpressing HA-Ub only, overexpressing both Flag-RBM39 and HA-Ub, and with simultaneously silenced DARS-AS1 and overexpressed Flag-RBM39/HA-Ub were cultured in a hypoxic environment for 24 h, and then cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody, followed by western blotting with anti-HA antibody. All cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h before collection. (D) Cell lysates from HEK293T cells overexpressing Flag-RBM39 only, overexpressing HA-Ub only, overexpressing both Flag-RBM39 and HA-Ub, and overexpressing DARS-AS1/Flag-RBM39/HA-Ub were immunoprecipitated with Flag antibody, followed by western blotting with anti-HA antibody. All cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h before collection. (E) Immunoblot analysis of Flag-tagged RBM39 [wildtype (WT) and truncation fragments] retrieved by in vitro-transcribed, biotinylated DARS-AS1. (F) The changes of truncated RBM39 after silencing DARS-AS1 were assessed using immunoblot analysis.

The RBM39 protein is composed of an arginine-serine domain at the N terminus, followed by three predicted RNA recognition motifs (RRM) (Figure 6E). We next constructed a series of RBM39 truncations (1-240, 241-400, 400-530, 1-400, and 241-530) to map its binding domains with the DARS-AS1. The deletion-mapping analyses identified the 1-240 amino acid sequence (corresponding to the RRM1 of RBM39) of RBM39 as required for its association with DARS-AS1 (Figure 6E). The truncated proteins containing the 1-240 amino acid fragment were downregulated, whereas the truncated RBM39 without amino acids 1-240 could not be degraded after the knockdown of DARS-AS1 under the hypoxic conditions (Figure 6F). These results suggest that the 1–240 amino acid sequence of RBM39 is essential for its binding to DARS-AS1.

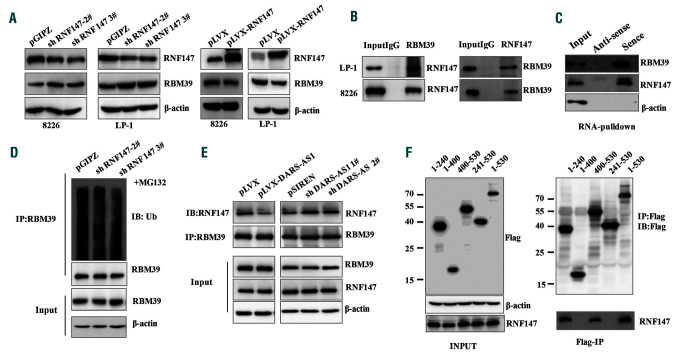

The interaction of DARS-AS1 with RBM39 inhibits the degradation of RBM39 through RNF147

Currently, the E3 ligases responsible for the ubiquitination of RBM39 are not clear. Several E3 ligases, including CHIP, RNF2, RNF147, and RNF113A, have been reported as possible RBM39-interacting proteins. Intriguingly, among the interacting proteins, the knockdown of RNF147 increased RBM39 protein levels and the overexpression of RNF147 decreased RBM39 protein levels in the hypoxic environment (Figure 7A, Online Supplementary S6B-D). A direct association between endogenous RBM39 and RNF147 was also revealed by the co-immunoprecipitation assays (Figure 7B). Using RNA pulldown assays, we further verified the association of DARS-AS1 with both RBM39 and RNF147 (Figure 7C). The immunoprecipitation assay showed that DARS-AS1 deficiency promoted endogenous RBM39 binding to RNF147, thereby increasing RNF147-mediated RBM39 ubiquitination in the hypoxic environment (Figure 7D, E). Additionally, in the hypoxic environment, RNF147 bound to the RRM1 domain of RBM39 which contains possible ubiquitin-modified lysines (Figure 7F, Online Supplementary Figure S6A). Together, these results indicate that DARS-AS1 may function as a mediator, which weakens the RBM39-RNF147 interaction, thereby diminishing RNF147-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of RBM39.

Figure 7.

DARS-AS1 inhibits RBM39 ubiquitination by weakening the RBM39–RNF147 interaction in a hypoxic environment. (A) The expression of RBM39 in RNF147 silenced/overexpressing myeloma cells in a hypoxic environment. (B) Cell lysates from myeloma cells were immunoprecipitated with RBM39/RNF147 antibody, followed by western blotting with antibody against RNF147/RBM39. (C) Cell lysates from RPMI 8226 cells cultured under hypoxic conditions were incubated with in vitro-synthesized, biotin-labeled sense or antisense DARS-AS1 for pulldown followed by immunoblot analysis. (D) HEK293T cells with stable knockdown of RNF147 were cultured in a hypoxic environment for 24 h, then treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-RBM39 antibody, followed by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody. (E) HEK293T cells with stable overexpression of DARS-AS1 or knockdown of DARS-AS1 were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody against RBM39. The precipitates and input were analyzed by immunoblotting. (F) Constructs for Flag-tagged RBM39 (wildtype and truncation fragment) were transfected into HEK293T cells, and then cultured in a hypoxic environment for 24 h. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-Flag M2 beads, and precipitates and input were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-RNF147 and anti-Flag antibodies.

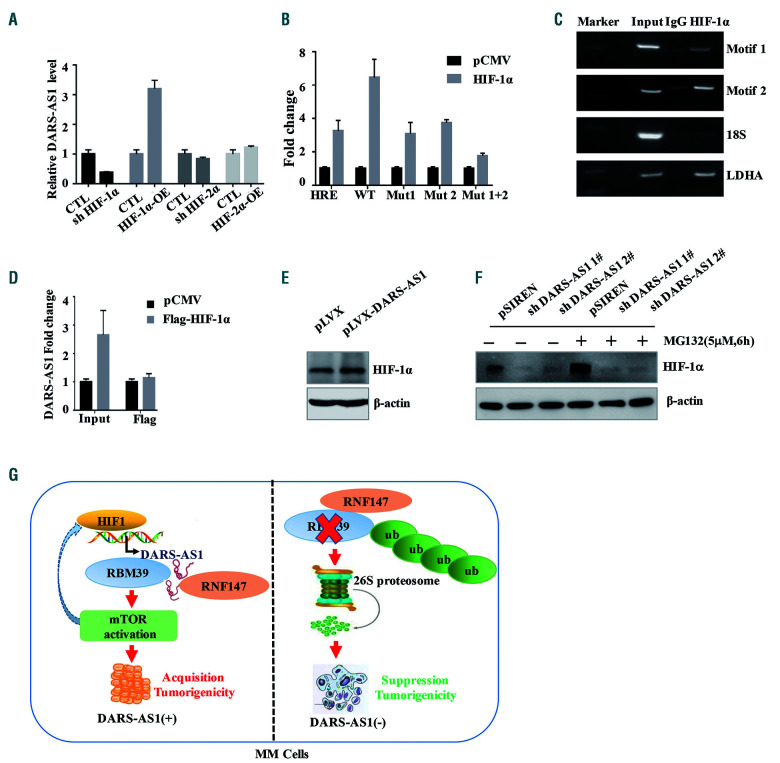

HIF-1α directly upregulates the expression of long non-coding RNA-DARS-AS1

To uncover the mechanisms of hypoxia-induced upregulation of DARS-AS1, we knocked down and overexpressed two well-known hypoxia-responsible transcriptional factors in HEK293T cells, HIF-1α and HIF-2α (Online Supplementary Figure S7A). Overexpression of HIF-1α, but not of HIF-2α, enhanced the expression of DARS-AS1; in the meantime, knockdown of HIF-1α substantially attenuated the hypoxia-induced DARS-AS1 upregulation (Figure 8A). HIF-1 acts by binding to an HRE upon hypoxia. There are two possible HRE in the promoter region of DARS-AS1 (http://jaspar.genereg.net) (Online Supplementary Figure S7B). To determine whether HIF regulates the expression of DARS-AS1 through these HRE, we constructed luciferase expression plasmids containing the promoter region (2000 bp) of DARS-AS1. As expected, HIF-1α strongly increased luciferase expression from the wildtype, but not the mutant HRE reporters (Figure 8B). At the same time, we used a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay to certify the binding of HIF-1 with the predicted two HRE regions (Figure 8C). Additionally, RNA immunoprecipitation assays showed that DARS-AS1 did not interact directly with HIF-1α (Figure 8D). Interestingly, the overexpression of DARS-AS1 upregulated the HIF-1α protein, whereas the knockdown of DARS-AS1 reduced the level of HIF-1α protein which could not be abolished by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in the hypoxic environment (Figure 8E, F). Moreover, DARS-AS1 could not influence the HIF-1α mRNA level in RPMI 8226 cells (Online Supplementary Figure S7C). We speculated that the DARS-AS1 silencing inhibited the translation of HIF-1α by suppression of the mTOR pathway.17,18 Altogether, HIF-1 enhanced the transcription activity of DARS-AS1; in turn, DARS-AS1 might accelerate the translation rate of HIF-1α expression via the mTOR pathway.

Figure 8.

HIF-1 directly upregulates the expression of DARS-AS1, which may, in turn, enhance the expression of HIF-1α. (A) HIF-1α or HIF-2α was knocked down or overexpressed in 293T cells. DARS-AS1 expression levels were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis and normalized to 18S rRNA. (B) Transient transfection of a DARS-AS1 promoter [wildtype (WT) or mutant] luciferase transcriptional reporter and plasmid overexpressing HIF-1α/control vector. The luciferase values were determined from cell lysates by normalization to renilla luciferase. The pGL3 control vector containing the HRE promoter was used as a positive control. The data represent the average and standard deviation of three independent experiments. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay certified the binding of HIF-1 with the predicted two HIF response element (HRE) regions; LDHA was used as a positive control. (D) RNA immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using a Flag-antibody (exogenous HIF-1α protein with Flag-tag), and specific primers to detect DARS-AS1. (E) The expression of HIF-1α in the RPMI 8226 cells overexpressing DARS-AS1 in a hypoxic environment was analyzed by immunoblotting. (F) DARS-AS1-knockdown RPMI 8226 cells were treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, 1:1000) or MG132 (5 μM) for 6 h. The expression of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions was analyzed by immunoblotting. (G) Proposed mode of action of DARS-AS1 in modulating myeloma tumorigenesis in a hypoxic environment. DARS-AS1 is directly regulated by HIF-1 and, in turn, promotes the expression of HIF-1α in myeloma. RBM39 mediates DARS-AS1-induced activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. DARS-AS1 stabilizes the RBM39 by interfering with E3 ligase RNF147-mediated ubiquitination. HIF-1/DARS-AS1/RBM39 signaling pathways are involved in the tumorigenesis of myeloma.

Discussion

Hypoxia-responsive genes are involved in the malignant progression and poor prognosis of human cancers.19 Numerous lncRNA have been reported to show abnormal expression in cancers.20 In the present work, we found that hypoxic-regulated DARS-AS1 was required for the survival and tumorigenicity of myeloma cells in vitro and in is a potential target for MM treatment.

DARS-AS1 is close to DARS in the genome (Online Supplementary Figure S4A). Numerous antisense lncRNA participate in physiological or pathological cellular processes through the regulation of the expression of its adjacent gene.21,22 By contrast, we found that the downregulation of DARS-AS1 was not associated with the expression of DARS at either transcriptional or protein levels (Online Supplementary Figure S4B-E). The DARS-AS1 gene has two annotated transcripts, NR_110199.1 and NR_110200.1, in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), with limited protein-coding potential (http://cpc.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) (Online Supplementary Figure S1E, F). The transcript of DARS-AS1 #2 (NR_110200.1) is not detectable in the myeloma cells. We, therefore, focused on DARS-AS1 #1 isoform in our gain- and loss-of-function studies.

Nutritional deficiency is common in the microenvironment of tumors. HIF-1, the protein that responds to low O2 concentrations, apparently leads to increased glycolysis, angiogenesis and drug resistance.1 In culture with low levels of glucose, the overexpression of DARS-AS1 suppressed myeloma cell apoptosis (Online Supplementary Figure S2D, E). More importantly, DARS-AS1 can promote the expression of HIF-1α. Thus, DARS-AS1 and HIF-1α may create a positive feedback, increasing the ability of myeloma cells to survive, although the underlying mechanism is not fully known. In addition, it would be interesting to examine the impact of DARS-AS1 on the prognosis of myeloma patients through the analysis of data from large numbers of samples.

The mass spectrometry and RNA pullown data revealed that DARS-AS1 interacts directly with RBM39, suppressing the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of RBM39 protein, an RNA-binding protein. Dysregulation of these types of proteins, which can lead to aberrant expression of cancer-related genes, has been widely observed in cancer cells.23,24 Previous studies suggested that RBM39 is a proto-oncogene in multiple cancer types. Our results extend this notion, indicating that RBM39 is a novel oncogene in myeloma. First, a significantly higher mortality risk was observed in patients with high expression of RBM39 than in those with lower expression. Second, activation of the mTOR signaling pathway reportedly plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of myeloma. Our results showed that the knockdown of RBM39 inhibited mTOR signaling, thus suggesting that RBM39 is critical for the proliferation and tumorigenesis of MM cells and may serve as a prognostic predictor for patients with MM. However, further investigations will be necessary to reveal the mechanisms of the regulation of the mTOR pathway by RBM39. Furthermore, similar results were observed in DARS-AS1 knockdown cells. The overexpression of RBM39 reversed the inhibition of mTOR signaling induced by the knockdown of DARS-AS1. Based on these data, we propose that the aberrant expression of DARS-AS1 in cells may increase the levels of RBM39, thereby triggering continuous activation of mTOR signaling.

Previous studies showed that sulfonamides have anticancer effects by promoting an interaction between RBM39 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase DCAF15, leading to the degradation of RBM39.12 However, RBM39 is not the endogenous substrate of DCAF15. To the best of our knowledge, in the present study we, for the first time, discovered that RBM39 is a substrate of the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF147. RNF147 is a member of the tripartite motif protein (TRIM) family and contains an N-terminal RING-domain, one or two B-boxes, and a coiled-coil region.25 We found that the RRM1 domain of RBM39, which contains the ubiquitin binding site domain (http://ubibrowser.ncpsb.org/, http://cplm.biocuckoo.org/), was responsible for the interaction with both DARS-AS1 and RNF147. Our results raise the possibility that DARS-AS1 may inhibit ubiquitination of RBM39 by competing with E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF147 for binding to RBM39. In fact, accumulating evidence shows that lncRNA can protect proteins from proteasome-mediated degradation. For instance, NKILA is a lncRNA that directly masks the phosphorylation motifs of IκB, thereby inhibiting the degradation of IκB and subsequently activating the NF-κB pathway.26 UPAT was found to inhibit the ubiquitination of epigenetic factor UHRF1 and play a critical role in the survival and tumorigenicity of tumor cells.27 In addition, LINC00673, as a cancer suppressor, was able to promote PTPN11 degradation, which weakened SRC–ERK signaling and increased STAT1-dependent antitumor effects.28 Our findings, together with the aforementioned earlier results, indicate that there is a class of lncRNA that regulate protein ubiquitination and degradation.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that DARS-AS1 has important functions in the hypoxic microenvironment of myeloma and may serve as a prognostic predictor for patients with MM. Our results indicate that the HIF-1/DARS-AS1/RBM39 pathway might provide a positive feedback loop that augments the HIF-1 response in myeloma, and that targeting this pathway may be pivotal in the prevention or treatment of myeloma. Our findings shed new light on the orchestrated interactions between HIF-1 and lncRNA in maintaining myeloma cell survival under hypoxia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Guoqiang Chen at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for providing plasmids.

Footnotes

Check the online version for the most updated information on this article, online supplements, and information on authorship & disclosures: www.haematologica.org/content/105/6/1630

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (n. 2017YFA0505200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (8167010684, 81570118), Shanghai Commission of Science and Technology (16ZR1421400), and the Science and Technology Committee of Shanghai (15401901800).

References

- 1.Maiso P, Huynh D, Moschetta M, et al. Metabolic signature identifies novel targets for drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2015;75(10):2071–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):629–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(3):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornienko AE, Guenzl PM, Barlow DP, Pauler FM. Gene regulation by the act of long non-coding RNA transcription. BMC Biol. 2013;11:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai MC, Spitale RC, Chang HY. Long intergenic noncoding RNAs: new links in cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71(1):3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: a new frontier of translational research¿ Oncogene. 2012;31(43):4577–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang G, Zhou Z, Wang H, Kleinerman ES. CAPER-alpha alternative splicing regulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor(1)(6)(5) in Ewing sarcoma cells. Cancer. 2012;118(8):2106–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung DJ, Na SY, Na DS, Lee JW. Molecular cloning and characterization of CAPER, a novel coactivator of activating protein-1 and estrogen receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(2):1229–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowhan DH, Hong EP, Auboeuf D, et al. Steroid hormone receptor coactivation and alternative RNA splicing by U2AF65-related proteins CAPERalpha and CAPERbeta. Mol Cell. 2005;17(3):429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang YK, Putluri N, Maity S, et al. CAPER is vital for energy and redox homeostasis by integrating glucose-induced mitochondrial functions via ERR-alpha-Gabpa and stress-induced adaptive responses via NF-kappaB-cMYC. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(4): e1005116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han T, Goralski M, Gaskill N, et al. Anticancer sulfonamides target splicing by inducing RBM39 degradation via recruit ment to DCAF15. Science. 2017;356 (6336). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sillars-Hardebol AH, Carvalho B, Tijssen M, et al. TPX2 and AURKA promote 20q amplicon-driven colorectal adenoma to carcinoma progression. Gut. 2012;61(11):1568–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477(7364):295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kogo R, Shimamura T, Mimori K, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR regulates poly-comb-dependent chromatin modification and is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20): 6320–6326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mai S, Qu X, Li P, Ma Q, Cao C, Liu X. Global regulation of alternative RNA splicing by the SR-rich protein RBM39. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1859(8):1014–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInturff AM, Cody MJ, Elliott EA, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates neutrophil extracellular trap formation via induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Blood. 2012;120(15):3118–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Q, Wang H, Jiang B, et al. Loss of ATF3 exacerbates liver damage through the activation of mTOR/p70S6K/ HIF-1alpha signaling pathway in liver inflammatory injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu A, Taylor M, Xue X, et al. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 2alpha promotes steatohepatitis through augmenting lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):472–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. 2013;154(1):26–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin W, Li X, Xie L, et al. A long non-coding RNA, APOA4-AS, regulates APOA4 expression depending on HuR in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(13):6423–6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villegas VE, Zaphiropoulos PG. Neighboring gene regulation by antisense long non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):3251–3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(14):1977–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MY, Hur J, Jeong S. Emerging roles of RNA and RNA-binding protein network in cancer cells. BMB Rep. 2009;42(3):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nisole S, Stoye JP, Saib A. TRIM family proteins: retroviral restriction and antiviral defence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(10):799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B, Sun L, Liu Q, et al. A cytoplasmic NF-kappaB interacting long noncoding RNA blocks IkappaB phosphorylation and suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(3):370–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taniue K, Kurimoto A, Sugimasa H, et al. Long noncoding RNA UPAT promotes colon tumorigenesis by inhibiting degradation of UHRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(5):1273–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng J, Huang X, Tan W, et al. Pancreatic cancer risk variant in LINC00673 creates a miR-1231 binding site and interferes with PTPN11 degradation. Nat Genet. 2016;48(7): 747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.