Abstract

On March 16, 2020, the French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics put online a national Question and Answer (Q&A) website, https://sfpt-fr.org/covid19 on the proper use of drugs during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The working group ‘Drugs and COVID‐19’ was composed of a scientific council, an editorial team, and experts in the field. The first questions were posted online during the first evening of home‐confinement in France, March 17, 2020. Six weeks later, 140 Q&As have been posted. Questions on the controversial use of hydroxychloroquine and to a lesser extent concerning azithromycin have been the most consulted Q&As. Q&As have been consulted 226 014 times in 41 days. This large visibility was obtained through an early communication on Twitter, Facebook, traditional print, and web media. In addition, an early communication through the French Ministry of Health and the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety ANSM had a large impact in terms of daily number of views. There is a pressing need to sustain a public drug information service combining the expertise of scholarly pharmacology societies, pharmacovigilance network, and the Ministry of Health to quickly provide understandable, clear, expert answers to the general population’s concerns regarding COVID‐19 and drug use and to counter fake news.

Keywords: COVID‐19, pharmacology, public drug information, public health

Introduction

Faced with the inexorable spread of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the French President, Emmanuel Macron, presented priorities for public action in response to the spread of COVID‐19 in a televised speech broadcast at 8 p.m. on March 12, 2020, that included mobilization of the French healthcare system. Compulsory home‐confinement was announced by the President at 8 p.m. on Monday, March 16, 2020, and during the night of March 16–17, the Interior Minister Christophe Castaner clarified the President’s instructions, with compulsory home‐confinement becoming effective from midday on Tuesday, March 17, 2020.

Very early on the French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics (SFPT) realized the gravity of the health situation, in particular for patients being treated for chronic diseases. The same day as the second presidential television broadcast, the SFPT’s scientific council had met (at 3 p.m.) and decided to create a national Question and Answer (Q&A) website within 24 h, https://sfpt‐fr.org/covid19 [1] to inform on the proper use of drugs during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The aim of the website was to give clear documented information about drug use during the COVID‐19 outbreak and to battle against misleading information or fake news. The first Q&As were posted on Tuesday, March 17, 2020.

Here, we report on the genesis of this emergency public drug information website from the SFPT, as well as website traffic after 6 weeks of existence.

Materials and Methods

The SFPT working group ‘Drugs and COVID‐19’ was created on March 16, 2020. It is composed of a scientific council, an editorial team, and experts in the field.

Scientific council

The SFPT scientific council defines the themes, oversees management of the web platforms, and interacts with the Public Health Authorities. It is responsible for all the content put online. The council also decides on the communication strategy and choice of educational materials required to reach the widest possible audience. The council’s mission is also to make the SFPT’s opinions and actions known to the health authorities in order to share common concerns, and finally to obtain endorsement that distinguishes its website from commercially sponsored or non‐scientific sites.

The objective of the web platform was first to answer questions from the general public about their medications for chronic diseases in the context of the pandemic and secondly to inform the public about medication use in the event of COVID‐19.

The first scientific council meeting was held on March 16 at 3 p.m., under the auspices of the SFPT. The members included the president and former president of the Society and the president of its scientific board; the two vice‐presidents and the former president of the French College of Medical Pharmacology (CNPM); the current and former presidents of the National Association of teachers in Therapeutics (APNET); and the president of the national network of pharmacovigilance centers. Later on, the president of the Clinical Pharmacy Faculty College (ANEPC), the president of the French Association of Addictovigilance Centers, and a representative of the young pharmacologists group of SFPT joined the scientific council. On March 29, 2020, this council had 15 members. The scientific council met every day excluding Sundays during the first two weeks, and less frequently thereafter. In order to coordinate with the French national government efforts, and for transparency, they invited representatives of the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (‘Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé, ANSM’), as well as of the Health directorate (‘Direction Générale de la Santé, DGS’), and the Public Health Information unit (‘Service Public d’Information en Santé’) of the French Ministry of Health. The objective is to coordinate our communication with the French Ministry of Health [2, 3] and ANSM [4]. In addition, a representative of the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology participated in the initial meetings.

Editorial team

The editorial team’s objective was to identify the questions, propose a first draft response and have the response amended and validated by two experts in the field, manage the flow of information between experts to reach a consensus, and post the answers online. It met daily, excluding Sunday, during the first 2 weeks, and every day excluding weekends thereafter. Q&As were posted with their first publication date. They were then updated daily if new data became available that warranted a response. The same review and validation process were used for the updated versions. Once the answers have been posted online, Prof. Alain Eschalier, professor emeritus of pharmacology at Clermont‐Ferrand, is in charge of on‐site proofreading.

The editorial committee analyses the statistics of https://sfpt‐fr.org/covid19 on a daily basis.

The questions came from several sources: 138 questions came from pharmacovigilance centers, emergency call centers or from direct questions by patients to the website, among which many relate to fake news. One question came from the scientific board (#136 on clinical trials) and one from the French Ministry of Health (#126 on povidone‐iodine).

Responses are based on systematic ongoing analyses of recommendations from scholarly societies, an ongoing systematic review of the literature from PubMed, Bibliovid [5], and Meta‐Evidence [6].

Field experts

Pairs of experts drawn from a board of 40 experts working in the field, mainly physicians and pharmacists, were responsible for proposing a documented response to each question within 24 h. The experts working in the field are alphabetically listed in the acknowledgement section and were suggested by the SFPT scientific council and contacted by the editorial team.

Statistical analysis

We collected and analyzed daily views of Q&As, drug information (and misinformation) spread in the media, media coverage of our website, and SFPT/ ANSM/ French Ministry of Health web communications from March 19 to April 28, 2020. The figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

On the first evening of home‐confinement, March 17, 2020, the first questions posted online were quickly relayed on Twitter and Facebook. Six weeks later, 140 Q&As have been posted and are updated on a daily basis following changes in recommendations and new scientific publications. Some of them have been enriched with small educational videos. The Q&As have been accessed 226 014 times between March 19, 2020, and April 28, 2020, and have been frequently relayed via multiple media (press, radio, TV) (Figures 1 , 2 and 1 , 2 ). An early communication through the French Ministry of Health and ANSM has helped to maintain the website’s visibility after the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France.

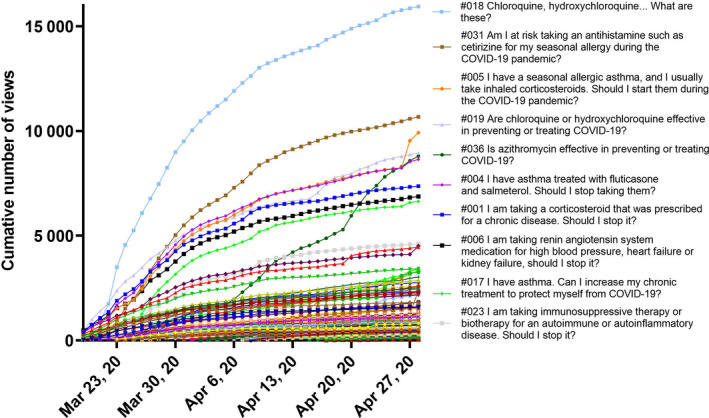

Figure 1.

Cumulative number of views of the 140 questions and answers from March 19, 2020, to April 28, 2020. Only the 10 most viewed questions and answers were kept in the graph legend.

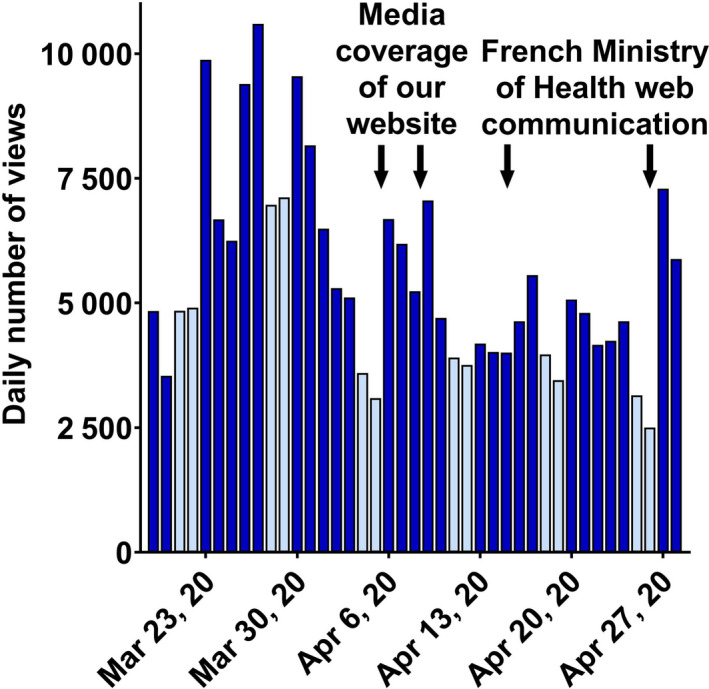

Figure 2.

Total daily views of the questions and answers from March 19, 2020, to April 28, 2020. Weekends are colored light blue. Arrows indicate the impact of media coverage and the French Ministry of health.

Overall analysis

We observed that the controversial questions concerning the controversial use of hydroxychloroquine and to a lesser extent azithromycin were the most frequently consulted (Figure 1 ) following the public release of the French cohort data on hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 [7].

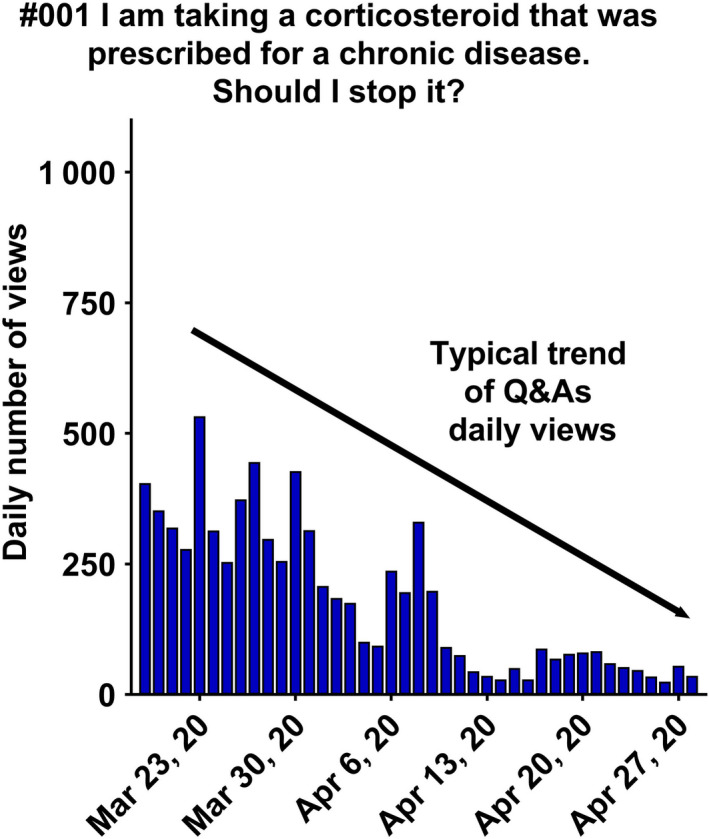

Interestingly, the 10 most viewed Q&As (see legend Figure 1 ) concerned the treatment of asthma, allergies, and chronic diseases, such as renin–angiotensin system medications, antihistamines, and corticosteroids. This was completely in line with our aim to inform patients about the safety of using their chronic disease treatment(s) during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The number of daily views widely varied over time. Most of the Q&As such as #018, #019, #031, #004, #001 had a peak of daily views soon after being posted online, and then, views decreased slowly over the following weeks (Figures 1 , 3 , 4 , 1 , 3 , 4 , and 1 , 3 , 4 ). We observed an important impact of scientific news, and announcements in web and print media or from the French Ministry of Health in terms of daily number of views (Figures 4 , 5 and 4 , 5 ).

Figure 3.

Individual daily views of question and answer (Q&A) #001 from March 19, 2020, to April 28, 2020, showing the general trend of website traffic for a single question.

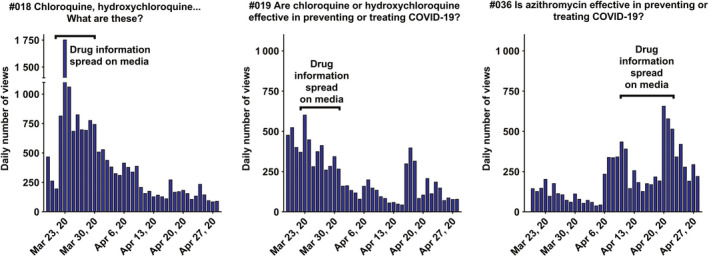

Figure 4.

Individual daily views of questions and answers #018, #019, #036 from March 19, 2020, to April 28, 2020, showing the influence of drug information spread on social networks and web, print and TV media.

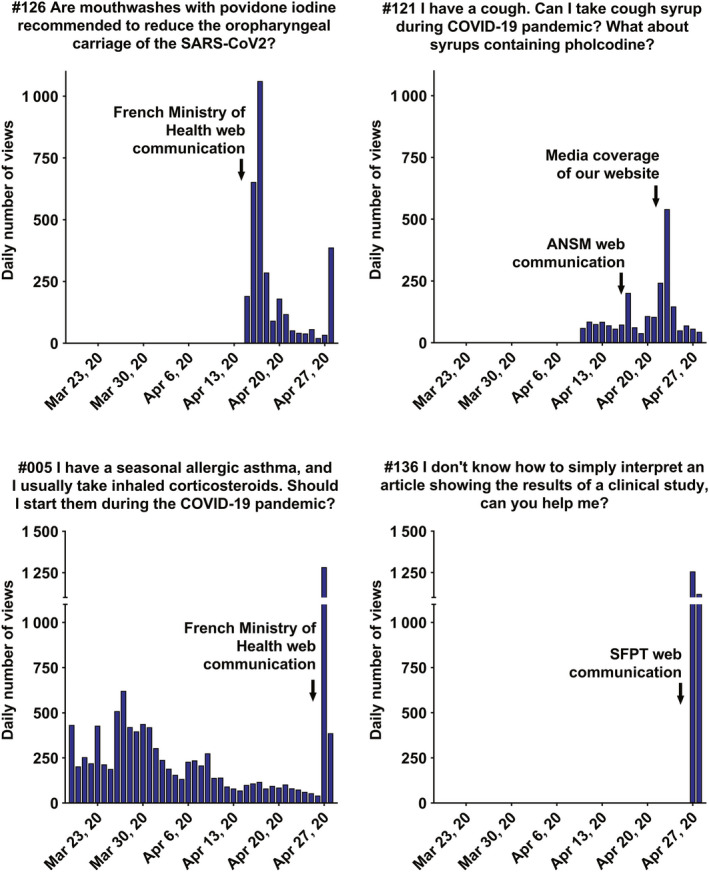

Figure 5.

Individual daily views of questions and answers #121, #126, #005 #136 from March 19, 2020, to April 28, 2020. Arrows indicate the high impact of web communication by The French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics (SFPT), the French Ministry of Health, French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety ANSM, and media coverage of our website.

The overall kinetics of Q&A views showed the highest number of views during the first two weeks (Figure 2 ). However, contrary to our expectations, daily views have remained high after one month, due to new Q&As, modifications in Q&As, and the high impact of communications from the establishment (e.g., the ANSM and the French Ministry of Health). Moreover, the website has been used by other websites and newspapers as a reliable source of information. For example, the online newspaper ‘The Conversation’ used information from our Q&As [8] for their article released online on April 9, 2020. This article was then reused under license by 6 other online newspapers and websites during the following week. All in all, continuous citation of our website by general media has helped to maintain a high daily number of views.

Detailed analysis of the most daily viewed Q&As

This analysis indicates the trends in the public’s concerns about potential treatments for COVID‐19 (Figures 3 , 4 , 5 – 3 , 4 , 5 ).

First, the use of hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 became the lead news item on French television and in the press the week after the release of results of a small clinical study using hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 [7]. Accordingly, our two Q&As (Figure 4 ) on hydroxychloroquine, in which we recommended against self‐medication and advised to wait for further results on its efficiency and safety, became our top viewed questions.

Then, azithromycin became one of the main subjects of concern (Figure 4 ). Announcements on TV and the Internet concerning hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin warned people about the potential cardiac side effects of hydroxychloroquine. On April 9, 2020, when the first information was released about a French cohort of 1061 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, the Q&A #036 topped of the daily views. People accessed Q&A #036 on azithromycin mostly when searching the keywords ‘azithromycin’ and ‘coronavirus’ on www.google.fr. Thanks to an early post on the SFPT site concerning azithromycin on March 20, 2020, Google displayed Q&A #036 on the first page of their search results, which gave the SFPT site a high impact in terms of daily number of views.

Such publicity had a huge impact on some other more specific Q&As. For example, Q&A #005 about seasonal allergic asthma benefited from a French Ministry of Health announcement. After a steady drop in daily views since being posted online, interest in the subject resurged and daily views rose from 42 to 1284 (Figure 5 ). This effect is reciprocal; Q&A #126 directly corrected emergent fake news on social media that recommended using povidone‐iodine as a mouthwash to decrease the oropharyngeal carriage of SARS‐CoV‐2. As soon as the Q&A appeared on our website, the French Ministry of Health released a warning on social media (Twitter, Facebook, etc.). The Q&A was viewed 1714 times in the next 48 h (Figure 5 ).

Finally, we are concerned about the large number of articles and comments circulating via social media questioning the methodological rigor of clinical trials. Q&A #136 was posted online as a guide to help the public understand clinical trials. The SFPT and its partners have also released communications on Q&A #136 through social media, resulting in the biggest jump in daily views for a Q&A, with 2378 views in 48 h (Figure 5 ).

Discussion

We report the first and largest website (to our knowledge) of Q&As answering specifically to patients about drug concerns during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Indeed, with 226 014 views in 41 days, this website seems to be meeting a popular demand. Its high visibility has been obtained through timely SFPT posts on Twitter, Facebook, and in traditional print and web media. In addition, an early communication through the French Ministry of Health and the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety ANSM had a large impact in terms of daily number of views.

Self‐medication with drugs of unproven efficacy and safety profile was a major concern for the French authorities. This website has enabled us to continuously monitor and quantify trends in the nature of questions posed by both patients and the general public, and as such represents a valuable indicator of people’s concerns about drug use.

In many countries, official Q&As websites have been set up to answer questions from the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Italian Ministry of Health, and the World Health Organization (WHO) websites posted respectively, at the date of April 28, 2020, approximately 36, 24, and 2 Q&As related to drugs and COVID‐19, respectively [9, 10, 11].

The WHO provided general guidelines as to the characteristics and contents that medicines regulatory authority websites should have in order to offer high quality drug information to consumers [12]. This included the need to offer reliable and unbiased drug information as a potential tool to help fight the inappropriate use of the Internet. However, in Europe the availability of advanced evidence‐based comparative drug information suitable for the general public is extremely heterogeneous. While regulatory information and safety alerts are available in all European countries, Germany and the United Kingdom stand out by showing an advanced framework of evidence‐based, comparative drug information for both health professionals and for the general population [13]. In the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, a striking concern is the amount of fake news and misleading information circulating worldwide that profoundly affects public health communication in all countries, as reported in Ireland [14], Italy [15], Japan [16], and India [17]. While the mass media must take responsibility for providing correct information and facilitating comprehension by citizens, the role of the SFPT as a scholarly society was to contribute to the national effort to provide reliable drug information. In addition, monitoring social media helps to anticipate questions from the population and fake news [18]. Before the pandemic, actions to counter health‐related misinformation circulating in social media were well described. They included identifying the emerging trends and prevalence of health misinformation, understanding how health misinformation is shared in the community, evaluating its influence on health, and finally developing interventions to fight it [19]. However, a recent analysis shows that during the present COVID‐19 health crisis [20], not only the appetite for information, but also demand for unproven and potentially hazardous COVID‐19 treatments is massive and is further increased by endorsements of public health leaders. In 2014, we had already forewarned that a major effort was badly needed in France to inform and educate both health professionals and the general public concerning drug use, and this in the absence of a crisis situation [21]. Current events highlight the need for scholarly societies, regulatory agencies, public health leaders, and the media to promote and amplify accurate and reliable information on drug use.

Our experience has several limitations. First, our initial priority was to inform the general population. However, it is clear that our Q&As went further than initially expected and we learned that many general practitioners, pharmacists, or healthcare workers were using our Q&As for themselves and to inform patients. If it is continued beyond the crisis, our website will have to evolve toward information at two levels: general population and health professionals. Another limitation was that we did not ask all committee members and experts for a public declaration of interest in the context of urgency. To date, only those involved in a public action, such as members of the pharmacovigilance network, have their public declaration posted online on the government website, and this should be corrected in the future in the case of this public drug information service is maintained beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic within the framework of a formal collaboration with the French Ministry of Health. Our collaboration with the Ministry of Health could have been more than just using their online communication channel. Indeed, the Ministry of Health relays information from the SFPT, but it remains the SFPT’s own initiative, responsibility, and funding. Future discussions should start about a public drug information service combining the expertise of the SFPT, the French pharmacovigilance network, and the French Ministry of Health.

Conclusion

There is a pressing need to sustain a public drug information service combining the expertise of scholarly pharmacology societies, pharmacovigilance network, and the Ministry of Health to quickly provide understandable, clear, expert answers to the general population’s concerns regarding COVID‐19 and drug use and to counter fake news.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alain Eschalier, professor emeritus of pharmacology at Clermont‐Ferrand, for proofreading Q&As on the website. We thank Isabelle Anglade (Direction Générale de la Santé), Mehdi Benkebil (ANSM), Patrick Maison (ANSM), Giovanna Marsico (Déléguée au Service Public d’Information en Santé), Christophe Ribuot (Université Grenoble Alpes, délégué à la francophonie), and Michael Spedding (International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, IUPHAR) for their implication in the communication of the website. We thank Nicolas Authier, Clermont‐Ferrand, for his important interview in ‘the Conversation’ on April 9, 2020. We thank Dr. Alison Foote (Grenoble‐Alpes University Hospital) for language editing of our manuscript. We would like to thank all the field experts who contributed to the web platform (in alphabetical order): Joachim Alexandre, Caen; Marc Bardou, Dijon; Laurent Becquemont, Paris; Lina Benajiba, Paris; Laurent Bertoletti, Saint Etienne; Marie Briet, Angers; Regis Bordet, Lille; Jean‐Luc Cracowski, Grenoble; Dominique Deplanque, Lille; David Devos, Lille; Béatrice Duly, Toulouse; Nathalie Fouilhé, Grenoble; Pierre‐Olivier Girodet, Bordeaux; Lauriane Goldwirt, Paris; Guillaume Grenet, Lyon; Romain Guilhaumou, Marseille; Philippe Guilpain, Montpellier; Annie‐Pierre Jonville‐Bera, Tours; Jéremy Jost, Limoges; Florentia Kaguelidou, Paris; Behrouz Kassai‐Koupai, Lyon; Charles Khouri, Grenoble; Jean‐Jacques Kiladjian, Paris; Maryse Lapeyre‐Mestre, Toulouse; Silvy Laporte, Saint Etienne; Claire Le Jeunne, Paris; Benedicte Lebrun‐Vignes, Paris; Marion Lepelley, Grenoble; Michel Mallaret, Grenoble; Joelle Micallef, Marseille; Frédéric Mille, Wissembourg; Mathieu Molimard, Bordeaux; Samia Mourah, Paris; Aurélie Portefaix, Lyon; Chantal Raherison, Bordeaux; Vincent Richard, Rouen; Bruno Revol, Grenoble; Matthieu Roustit, Grenoble; Emilie Sbidian, Paris; Arnaud Tanty, Grenoble; Thierry Vial, Lyon; Elisa Vitale, Grenoble.

References

- 1. Société Française de Pharmacologie et de Thérapeutique . Groupe de travail « médicaments et COVID‐19 ». 2020. https://sfpt‐fr.org/covid19

- 2. Ministère des solidarités et de la santé Français . Réponses à vos questions sur les médicaments pendant la crise du COVID‐19. 2020. http://solidarites‐sante.gouv.fr/soins‐et‐maladies/maladies/maladies‐infectieuses/coronavirus/tout‐savoir‐sur‐le‐covid‐19/article/reponses‐a‐vos‐questions‐sur‐les‐medicaments‐pendant‐la‐crise‐du‐covid‐19.

- 3. Ministère des solidarités et de la santé Français . Questions ‐ Réponses COVID‐19 et bon usage du médicament | Santé.fr. 2020. https://sante.fr/questions‐reponses‐covid‐19‐et‐bon‐usage‐du‐medicament.

- 4. Agence Nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé . COVID 19. Vous avez des questions sur vos traitements? 2020. https://www.ansm.sante.fr/Dossiers/COVID‐19/Des‐questions‐sur‐votre‐traitement‐dans‐le‐contexte‐de‐l‐epidemie‐COVID‐19.

- 5. Veille scientifique sur le COVID‐19, 2020. https://bibliovid.org/.

- 6. Meta‐Evidence on COVID‐19. http://metaevidence.org/COVID19.aspx.

- 7. Gautret P., Lagier J.‐C., Parola P. et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. (2020) 105949. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The conversation online newspaper. https://theconversation.com/quels‐medicaments‐peut‐on‐encore‐prendre‐pendant‐lepidemie‐de‐covid‐19‐134276.

- 9. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . Frequently asked questions ‐ COVID‐19. https://www.fda.gov/emergency‐preparedness‐and‐response/coronavirus‐disease‐2019‐covid‐19/coronavirus‐disease‐2019‐covid‐19‐frequently‐asked‐questions#drugs.

- 10. The Italian Ministry of Health . Frequently asked questions ‐ COVID‐19. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioFaqNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=english&id=230#6.

- 11. The World Health Organization (WHO) . Frequently asked questions ‐ COVID‐19. https://www.who.int/news‐room/q‐a‐detail/q‐a‐coronaviruses.

- 12. Model website for medicines regulatory authorities . WHO, 2020.https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/regulation_legislation/model_site/en/.

- 13. Formoso G., Font‐Pous M., Ludwig W.‐D. et al. Drug information by public health and regulatory institutions: Results of an 8‐country survey in Europe. Health Policy. (2017) 121(3) 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor C., Murphy M. Going viral: doctors must tackle fake news in the covid‐19 pandemic. BMJ. (2020) 24(369) m1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rovetta A., Bhagavathula A.S. Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19)‐related web search behavior and infodemic attitude in Italy: Infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020).6(2):e19374. 10.2196/19374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shimizu K. 2019‐nCoV, fake news, and racism. Lancet. (2020) 395(10225) 685–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kadam A.B., Atre S.R. Social media panic and COVID‐19 in India. J. Travel. Med. (2020). 10.1093/jtm/taaa057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abd‐Alrazaq A., Alhuwail D., Househ M., Hamdi M., Shah Z. Top concerns of tweeters during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Infoveillance study. J. Med. Internet Res. (2020) 22 e19016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chou W.‐Y.S., Oh A., Klein W.M.P. Addressing health‐related misinformation on social media. JAMA. (2018) 320 2417–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu M., Caputi T.L., Dredze M., Kesselheim A.S., Ayers J.W..Internet Searches for Unproven COVID‐19 Therapies in the United States. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. (2020). [cited 2020 May 1]; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2765361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Molimard M., Bernaud C., Lechat P. et al. Information and communication on risks related to medications and proper use of medications for healthcare professionals and the general public: precautionary principle, risk management, communication during and in the absence of crisis situations. Therapie [Internet]. (2014) 69 361–366. [cited 2020 May 1]. Available from: https://www.journal‐therapie.org/articles/therapie/abs/2014/04/th142246/th142246.html [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]