Abstract

The value of serological testing to inform the public health response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is debated. Using a transmission model, we examined how serology can be implemented to allow seropositive individuals to resume more normal levels of social interaction while offsetting the risks. We simulated the use of widespread serological testing with realistic assay characteristics, in which seropositive individuals partially restore their social contacts and act as immunological ‘shields’. If social distancing is relaxed by 50% at the same time that quarterly serological screening is initiated, approximately 120,000 deaths could be averted and a quarter of the US population could be released from social distancing in the first year of the epidemic, compared to a scenario without serological testing. This strategy has the potential to substantially flatten the COVID-19 epidemic curve while also allowing a substantial number of individuals to safely return to social and economic interactions.

One Sentence Summary:

Informing relaxation of social distancing with serological testing can reduce population risk while offsetting some of the severe social and economic costs of a sustained shutdown.

SARS-CoV-2 emerged in China in late 2019 leading to a pandemic of COVID-19, with over 4.1 million detected cases and over 285,000 deaths globally as of May 11, 2020 (1). In the United States (U.S.), 1.3 million cases and 85,000 deaths were reported by that date (1). Unprecedented social distancing measures have been enacted to reduce transmission and thereby blunt the epidemic peak (i.e. “flatten the curve”). In early March, U.S. states began to close schools, suspend public gatherings, and encourage employees to work from home if possible. On March 17, 2020, the U.S. government issued national social distancing guidelines, leading to wider implementation of such policies. By mid-April, 95% of the U.S. (2) and over 30% of the global population were under some form of shelter-in-place order (3). Federal social distancing guidelines expired on April 30, 2020; in late April and May, many state and local governments relaxed stay-at-home orders partially or completely to move towards ‘re-opening’ (4).

Relaxing these initially effective social distancing policies will result in increased contacts and community transmission (5). A return to ‘business as usual’ will likely lead to exponential growth in cases, exceeding the capacity of health services (6). With the goal of maintaining the reproductive number at or less than one, public health efforts could allow a gradual return to some activities (4). Some degree of social distancing, together with enhanced hygiene and wearing of face masks, is likely to be maintained with stricter distancing measures for individuals at higher risk (7). Alongside these measures, widespread serological testing programs may help inform these new social distancing strategies while keeping deaths and hospital admissions at sufficiently low levels.

Recent serosurveys of SARS-CoV-2 in the U.S. vary in their estimates of seroprevalence but collectively suggest that infections likely far outnumber documented cases (8–10). If detectable antibodies serve as a correlate of immunity, serological testing may be used to identify protected individuals (11). While our understanding of the immunological response to SARS-CoV-2 infection remains incomplete, the vast majority of individuals experience seroconversion after infection (12) and convalescent plasma from recovered COVID-19 cases appears to improve outcomes in critically ill patients (13–15). Together, these data suggest that recovered individuals have some protection against subsequent reinfection. Once identified, test-positive individuals could return to pre-pandemic levels of social interactions and act as ‘shields’ (16). In this strategy, individuals who test positive would preferentially replace susceptible individuals in physical interactions, such that more contacts are between susceptible and immune individuals rather than between susceptible and potentially infectious individuals.

Such strategies, however, rely on correctly identifying immune individuals. There are currently twelve serological assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies that have been approved for emergency use by Food and Drug Administration (17) with many others currently in development and approved in other countries (18). The performance of these tests vary considerably (17, 19, 20). For the purpose of informing social distancing policies, specificity rather than sensitivity is of primary concern. An imperfectly specific test will result in false positives, leading to individuals being incorrectly classified as immune. If used as a basis to relax social distancing measures, there is concern that this error could heighten risk for individuals who test positive and lead to an increase in community transmission.

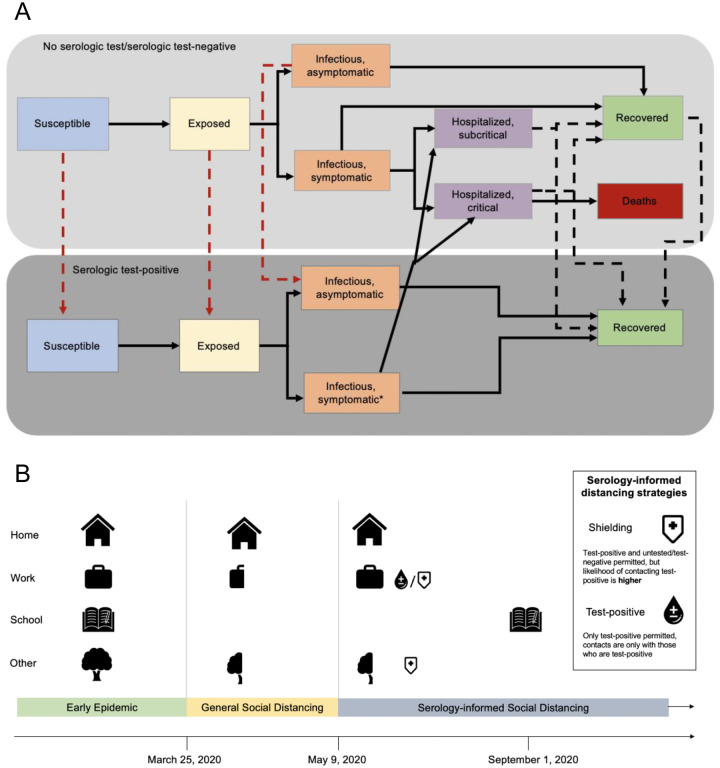

We modeled the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 using a deterministic, compartmental SEIR-like model calibrated to death data (https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data) and ICU admissions (https://covidtracking.com/api). (Figure 1, Figure S1, Table S1) Recovered, susceptible, latently infected, and asymptomatic at rates that are functions of testing frequency, sensitivity (for recovered individuals), and specificity (for non-immune individuals). (Figure 1A) We model contacts at home, work, school, and other locations among three age groups: children and young adults (<20 years), working adults (20–64 years), and elderly (65+ years).

Figure 1.

Methods diagram overview A) Overall model diagram. Serological antibody testing is shown by dashed arrows. Red dashed arrows indicate false positives (i.e., someone is not immune, but is moved to the test positive group) and occur at a rate that is a function of 1-specificity. True positives occur at a rate that is a function of the sensitivity. *Symptomatic infections in the test-positive group have similar severity to symptomatic infections in the not tested/test negative group, but symptoms are not recognized as being caused by SARS-CoV-2 unless symptoms are severe enough to warrant hospitalization. B) Schematic of modeled interventions. General social distancing reduces work, school and other contacts beginning on March 25, 2020 and these contacts are gradually reintroduced beginning on May 9, 2020 with schools and daycares re-opening on September 1, 2020.

On March 17, 2020, the U.S. federal government released guidance recommending working from home, postponing unnecessary travel, and limiting gatherings to less than 10 people (21). Under these measures, we assume all contacts at school and daycare were eliminated and contacts outside of home, work, and school (‘other’) locations were reduced by 75% (22) while contacts at home remained unchanged. In accordance with state and local governments relaxing distancing policies, we assume social distancing measures for the general population are relaxed starting May 9. At this time, work and other contacts are scaled to a proportion of their value under general social distancing based on a scalar constant, c, such that c=1 is equivalent to the scenario in which social distancing measures as put into place on March 17 are maintained and c=0 is equivalent to a return to pre-pandemic contact levels. We assume that schools and daycares remain closed until September 1, 2020 and that test-negative/untested individuals continue to work from home. (Figure 1B)

Individuals who test positive return to work and increase other contacts to normal levels. To reflect the placement of test-positive individuals in high-contact roles, we assume that contacts at work and other (non-home, non-school) locations are preferentially with test-positive persons. When shielding is 5:1, this implies that the probability of interacting with a test-positive individual is 5 times what would be expected given the frequency of test-positives in the population (α=4), following the model of ‘fixed shielding’ (described in (16)).

We consider a high-performance test with a specificity of 99.8%, consistent with the recently approved Roche assay, and a sub-optimal test with 96% specificity (similar to the approved Cellex assay) (17). We set test specificity to 50% to represent a scenario in which antibodies are not a reliable correlate of immunity, (i.e., the test cannot distinguish between immune and non-immune individuals).

Without any intervention, our model predicts that 86% of the US population would be infected with SARS-CoV-2 by January 2021, resulting in 940,000 deaths. Social distancing has the potential to greatly reduce this burden, with indefinite social distancing reducing cumulative deaths by 88% and leading to a flattened epidemic curve. If social distancing measures are relaxed prematurely, incidence rebounds and the benefit of early distancing is lost by the end of the epidemic (Figure S2, Table S2).

Reductions in social distancing may be implemented simultaneously with serological testing to reduce deaths and healthcare system burden (Figure 2, Figure 3). If social distancing measures are relaxed such that adults only reduce their contacts by 40% compared with pre-pandemic levels (c=0.5, Table S3) and schools reopen in the fall, 556,000 deaths would be expected by January 2021 (Figure 2). However, if annual serological testing of the US population (1 million tests/day) is implemented alongside relaxation of social distancing, expected deaths fall to 437,000, saving 119,000 lives. If monthly testing is achieved (10 million tests/day), expected deaths fall to 235,000, saving 321,000 lives. With monthly testing, 29% of the U.S. population would test positive by the end of one year and be able to return to work and increase other social contacts to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 3); 26% if annual testing is used.

Figure 2.

The top row shows cumulative deaths by January 15, 2021 assuming schools reopen on September 1, 2020 for No Shielding (α=0) (left) and 5:1 Shielding (right). Colored lines show the extent of relaxing social distancing measures, based on the value of c. Dotted lines show results for a weak immunity scenario, solid lines show results for a suboptimal test (96% specificity), and dashed line shows results for a high-performance test (99.8% specificity). The bottom row shows the fraction of the US population released from social distancing after 1 year for No Shielding (left) and 5:1 Shielding (right). Line colors correspond to testing levels; blue is monthly testing (10 million tests/day) of the US population. Results shown assume a 50% relaxation of current social distancing levels for work and other contacts for those untested or testing negative and assume a test sensitivity of 100%.

Figure 3.

Critical care cases over time by testing level (colors) and relaxation of social distancing levels (panels). c is the factor by which non-home, non-school contacts are reduced from their initial values. All panels assume schools reopen on September 1, 2020. The U.S. critical capacity is shown by the solid black line (97,776 beds (24))

The magnitude of this benefit depends on both the degree of immunological shielding and test specificity. If α=0 (no shielding), 557,000 deaths would be expected with monthly testing of the U.S. population, similar to if testing were not implemented at all. Higher levels of shielding could reduce population risk further if a highly specific test is used, with monthly testing leading to 180,000 deaths after one year (Figure S3). Using a less specific test (such as (23)) could increase population risk. For example, if monthly testing with a suboptimal assay were implemented without immunological shielding and a 50% relaxation in social distancing, 85% of the US population would be released from social distancing but 587,000 deaths would be expected, 31,000 more than if no testing were implemented.

Using a highly specific test (99.8% specificity), the fraction of the test positive population who remain susceptible at the end of the epidemic remains small (Figure S4). Testing about half of the U.S. population once a year is roughly equivalent to a 10% increase in social distancing intensity. (Figure 4) If social distancing is relaxed to pre-pandemic levels, higher levels of testing can lead to an increase in deaths if infection prevalence remains low due to a higher rate of false positives (lower positive predictive value). (Figure 3)

Figure 4.

Contour plot of A) cumulative deaths and B) number of people released from social distancing as a function of the degree of relaxation of social distancing (1-c) and testing rate, on the log scale. Both panels assume a test specificity of 0.998 and a shielding factor of 5:1 (α=4).

For all scenarios, sustaining moderate levels of social distancing for test-negative and untested individuals can reduce peak epidemic burden (Figure 3). An immediate return to pre-pandemic levels of work and ‘other’ contacts would result in a peak burden of 269,000 critical care patients in late June. In contrast, delaying school opening until September and lower levels of social distancing (c=0.75, equivalent to total contacts reduced by 17.9% for adults), peak burden would be 45,000–118,000 critical care patients, near or below the current critical care capacity in the U.S. (estimated at 97,776 beds (24)).

Reopening schools in early fall is unlikely to trigger a second wave of infections unless nationwide lockdown is maintained until the start of the academic year (c=1). A secondary peak is more likely during the summer, after social distancing measures are initially relaxed. Note that our model does not account for any seasonal variation in transmissibility, which may impact SARS-CoV-2 transmission (25, 26).

There is an urgent need to identify strategies to permit safely easing social distancing measures and returning to productive levels of economic and social activity. Our results suggest that serological testing can make a substantial contribution to these efforts. Maintaining moderate social distancing (i.e., at half the current level) together with widespread serological testing (at least yearly testing) could release 24% of the population from social distancing by January 15, 2021. Moreover, if moderate shielding is employed, a strategy with serological testing results in up to 321,000 fewer deaths than a strategy without testing. Moderate relaxation of social distancing and shielding alongside monthly testing results in a flattened curve that provides time to improve treatments and expand healthcare capacity, which could further reduce mortality rates (26). Thus, serological testing would allow a substantial fraction of the population to return to work and other activities with relative safety, compared to a universal rollback of social distancing policies (Figure S2, Table S2).

An aggressive testing approach (one million tests per day) may appear unprecedented but is feasible. Other countries including Germany have implemented widespread serological testing, including repeat testing of the same individuals on a regular (i.e. monthly) basis (27). Although this would require a significant and rapid scale-up of testing capacity in the U.S., this has already been achieved for diagnostic PCR testing: the U.S. expanded testing from fewer than 1,000 tests per day in early March to nearly 250,000 tests per day in mid-May. Moreover, recently developed serologic tests are quicker to perform than RT-PCR, with a potential throughput of 300 tests/hour/machine, compared with 94 RT-PCR tests performed every 3 hours (28, 29). One manufacturer of these tests projects tens of millions of tests will be available by the end of May with capacity ramping up thereafter (28). Including other assays with similar performance as part of an overall testing strategy further improves feasibility.

Even if testing can be scaled up, legal and ethical concerns remain. Requiring evidence of a positive test to return to work creates strong incentives for individuals to misrepresent their immune status or intentionally infect themselves. A mass testing program must consider how such policies might enforce existing social disparities and guard against inequities in test availability (30, 31). Relatedly, a history of a positive antibody test should not change the clinical care of individuals with respiratory symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection if a PCR diagnostic test would otherwise be indicated.

While others have raised concerns that using an imperfect test to relax social distancing could increase population risk, we show that available diagnostic tests can form the basis of a successful shielding strategy. If testing employs the most specific assays available, the false positive rate would remain low and deploying immune individuals such that they are responsible for more interactions than susceptible individuals will decrease risk. If shielding is not employed, this benefit disappears and testing can become a liability, which explains why our findings differ from others who have examined the potential impact of serologic testing programs (32). In our model, cumulative deaths are not substantially impacted by the false positive rate: deaths are similar under scenarios assuming a sub-optimally specific test (96% specificity) and a high-performance test (99.8% specificity) except at very high testing rates. Thus, false positives are unlikely to substantively impact population-level risk at levels of specificity reported by recently authorized serologic tests (17, 33).

Although false positives are more important than false negatives for transmission risk, sub-optimal sensitivity also has implications for a mass testing strategy. Several recently authorized tests report near-perfect sensitivity, but these estimates were made under ideal conditions which are unlikely to reflect the realities of a mass testing program (17). Testing too soon after exposure or using a less sensitive test would reduce the cost-effectiveness of testing by missing truly immune individuals. Complementing serologic testing with PCR-based viral diagnostic testing could substantially increase the pool of test-positive individuals able to return to work and other activities. Strategies that employ both tests should be the subject of future studies.

Our models assumed random allocation of serological testing. In practice, targeting testing to specific groups, such as healthcare workers, nursing home care providers, food service employees, or contacts of confirmed or suspected cases might increase efficiency by increasing the test positive rate (and consequently, cost-effectiveness (34)), allowing for similar numbers of individuals to be released from social distancing at lower testing levels. This strategy would also decrease the false positive rate, an important consideration if a less specific test is used(35). Many healthcare organizations have already begun to offer antibody testing to their employees (36). The use of serological testing and shielding within healthcare settings represents a potential application of a more targeted strategy.

Compared to maintaining current levels of lockdown, relaxing social distancing always results in higher COVID-19 incidence in our models. However, policymakers and society-at-large may consider these trade-offs acceptable, given the high social and economic costs of sustained social distancing. Importantly, this calculation may change over time: the benefits of a serological testing and shielding strategy may decline as incidence declines, as the positive predictive value of the test declines and the number of individuals that test positive plateaus. The success of this strategy also depends on the degree to which shielding can be implemented. We have assumed a moderate degree of shielding (16); the extent to which it is possible to implement this in different settings will vary.

There remains much to learn about immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and we have made three critical simplifying assumptions in our model. First, we assume that antibodies are immediately detectable after resolution of infection. In reality, this likely occurs between 11 to 14 days post infection (37), similar to SARS-CoV-1 (38). A small fraction of recent infections would be undetected, but this would have a minor effect on our results. Second, we assume that immunity lasts for at least a year. Given that the virus has only been circulating for a matter of months in humans, both the duration of antibody protection and the extent to which those antibodies protect against future infections is unknowable. However, most individuals who are infected seroconvert (12), and ongoing studies of SARS-CoV-2 show that antibodies persist for at least 7 weeks (37). Third, we assume that antibodies detected by serology are a correlate of protection. Antibody kinetics of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS suggest that protection will last for at least months and as long as several years (38).

A serological testing strategy is only one component of the public health response to COVID-19, alongside diagnostic testing, rigorous contact tracing, and isolation efforts. If implemented simultaneously, such measures would likely reduce the extent of shielding required to achieve the same benefit, in addition to further reducing overall transmission.

In summary, our results suggest a role for a serological testing program in the public health response to COVID-19. While maintaining a degree of social distancing, serology can be used to allow people with positive test results to return to work and other activities while mitigating the health impacts of COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Timothy Lash, Andreas Handel, Carly Adams, Julia Baker, Carol Liu and Avnika Amin for useful comments.

Funding: BAL and ANMK were supported by the Vaccine Impact Modelling Consortium; BAL and KNN were supported by NIH/NICHD R01 HD097175; BAL, KNN, and ANMK were supported by NIH/NIGMS R01 GM124280; JSW was supported by Simons Foundation (Scope Award ID 329108); JSW and CZ were supported by the Army Research Office (W911NF1910384); JSW was supported by National Science Foundation (1806606 and 1829636).

Footnotes

Competing interests: BAL reports grants and personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and personal fees from World Health Organization outside the submitted work.

Data and materials availability: Data used for model calibration are available from ‘https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data’ and ‘https://covidtracking.com/api’. Code is available at ‘https://github.com/lopmanlab/Serological_Shielding’

References and Notes:

- 1.COVID-19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, (available at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html).

- 2.Woodward Aylin H. S., About 95% of Americans have been ordered to stay at home. This map shows which cities and states are under lockdown. Business Insider, (available at https://www.businessinsider.com/us-map-stay-at-home-orders-lockdowns-2020-3). [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFall-Johnsen Lauren Frias J. K., Morgan A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown — here’s our constantly updated list of countries and restrictions. Business Insider, (available at https://www.businessinsider.com/countries-on-lockdown-coronavirus-italy-2020-3). [Google Scholar]

- 4.National coronavirus response: A road map to reopening. American Enterprise Institute - AEI, (available at https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/national-coronavirus-response-a-road-map-to-reopening/).

- 5.Ferguson N., “Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand,” (available at https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yamana T., Pei S., Shaman J., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.04.20090670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X., Du Z., Huang G., Pasco R., Fox S., Galvani A., Pignone M., Johnston S. C., Meyers L. A., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.03.20089920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J., Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2). Science, eabb3221 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoehl S., Rabenau H., Berger A., Kortenbusch M., Cinatl J., Bojkova D., Behrens P., Böddinghaus B., Götsch U., Naujoks F., Neumann P., Schork J., Tiarks-Jungk P., Walczok A., Eickmann M., Vehreschild M. J. G. T., Kann G., Wolf T., Gottschalk R., Ciesek S., Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Returning Travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 382, 1278–1280 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabata S., Imai K., Kawano S., Ikeda M., Kodama T., Miyoshi K., Obinata H., Mimura S., Kodera T., Kitagaki M., Sato M., Suzuki S., Ito T., Uwabe Y., Tamura K., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutts F. T., Hanson M., Seroepidemiology: an underused tool for designing and monitoring vaccination programmes in low- and middle-income countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 21, 1086–1098 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wajnberg A., Mansour M., Leven E., Bouvier N. M., Patel G., Firpo A., Mendu R., Jhang J., Arinsburg S., Gitman M., Houldsworth J., Baine I., Simon V., Aberg J., Krammer F., Reich D., Cordon-Cardo C., “Humoral immune response and prolonged PCR positivity in a cohort of 1343 SARS-CoV 2 patients in the New York City region” (preprint, Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS), 2020),, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.30.20085613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan K., Liu B., Li C., Zhang H., Yu T., Qu J., Zhou M., Chen L., Meng S., Hu Y., Peng C., Yuan M., Huang J., Wang Z., Yu J., Gao X., Wang D., Yu X., Li L., Zhang J., Wu X., Li B., Xu Y., Chen W., Peng Y., Hu Y., Lin L., Liu X., Huang S., Zhou Z., Zhang L., Wang Y., Zhang Z., Deng K., Xia Z., Gong Q., Zhang W., Zheng X., Liu Y., Yang H., Zhou D., Yu D., Hou J., Shi Z., Chen S., Chen Z., Zhang X., Yang X., Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117, 9490–9496 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L., Xiong J., Bao L., Shi Y., Convalescent plasma as a potential therapy for COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20, 398–400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyner M., Wright R. S., Fairweather D., Senefeld J., Bruno K., Klassen S., Carter R., Klompas A., Wiggins C., Shepherd J. R., Rea R., Whelan E., Clayburn A., Spiegel M., Johnson P., Lesser E., Baker S., Larson K., Sanz J. R., Andersen K., Hodge D., Kunze K., Buras M., Vogt M., Herasevich V., Dennis J., Regimbal R., Bauer P., Blair J., van Buskirk C., Winters J., Stubbs J., Paneth N., Casadevall A., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.12.20099879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weitz J. S., Beckett S. J., Coenen A. R., Demory D., Dominguez-Mirazo M., Dushoff J., Leung C.-Y., Li G., Măgălie A., Park S. W., Rodriguez-Gonzalez R., Shivam S., Zhao C. Y., Modeling shield immunity to reduce COVID-19 epidemic spread. Nature Medicine, 1–6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.C. for D. and R. Health, EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance. FDA (2020) (available at https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance). [Google Scholar]

- 18.J. website administrator, Global Progress on COVID-19 Serology-Based Testing. Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, (available at https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/resources/COVID-19/serology/Serology-based-tests-for-COVID-19.html). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams E. R., Anand R., Andersson M. I., Auckland K., Baillie J. K., Barnes E., Bell J., Berry T., Bibi S., Carroll M., Chinnakannan S., Clutterbuck E., Cornall R. J., Crook D. W., Silva T. D., Dejnirattisai W., Dingle K. E., Dold C., Eyre D. W., Farmer H., Hoosdally S. J., Hunter A., Jeffrey K., Klenerman P., Knight J., Knowles C., Kwok A. J., Leuschner U., Liu C., Lopez-Camacho C., Matthews P. C., McGivern H., Mentzer A. J., Milton J., Mongkolsapaya J., Moore S. C., Oliveira M. S., Pereira F., Peto T., Ploeg R. J., Pollard A., Prince T., Roberts D. J., Rudkin J. K., Screaton G. R., Semple M. G., Skelly D. T., Smith E. N., Staves J., Stuart D., Supasa P., Surik T., Tsang P., Turtle L., Walker A. S., Wang B., Washington C., Watkins N., Whitehouse J., Beer S., Levin R., Espinosa A., Georgiou D., Garrido J. C. M., Thraves H., Lopez E. P., del R M.. Mendoza F., Diaz A. J. S., Sanchez V., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.15.20066407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassaunière R., Frische A., Harboe Z. B., Nielsen A. C., Fomsgaard A., Krogfelt K. A., Jørgensen C. S., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing. The White House, (available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-4/).

- 22.Quantifying interpersonal contact in the United States during the spread of COVID-19: first results from the Berkeley Interpersonal Contact Study | medRxiv, (available at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.13.20064014v1).

- 23.qSARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test, (available at https://www.fda.gov/media/136622/download).

- 24.Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2020. | AHA, (available at https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals).

- 25.Chan K. H., Peiris J. S. M., Lam S. Y., Poon L. L. M., Yuen K. Y., Seto W. H., The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Advances in Virology. 2011 (2011), p. e734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kissler S. M., Tedijanto C., Goldstein E., Grad Y. H., Lipsitch M., Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science, eabb5793 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennhold K., Vancon L., With Broad, Random Tests for Antibodies, Germany Seeks Path Out of Lockdown. The New York Times (2020), (available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/world/europe/with-broad-random-tests-for-antibodies-germany-seeks-path-out-of-lockdown.html). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche’s COVID-19 antibody test receives FDA Emergency Use Authorization and is available in markets accepting the CE mark, (available at https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2020-05-03.htm).

- 29.TaqPath COVID-19 Multiplex Diagnostic Solution - US, (available at https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/clinical/clinical-genomics/pathogen-detection-solutions/coronavirus-2019-ncov/genetic-analysis/taqpath-rt-pcr-covid-19-kit.html).

- 30.Phelan A. L., COVID-19 immunity passports and vaccination certificates: scientific, equitable, and legal challenges. The Lancet. 0 (2020), doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31034-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norheim O. F., Protecting the population with immune individuals. Nature Medicine, 1–2 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray N., Calleja D., Wimbush A., Miralles-Dolz E., Gray A., De-Angelis M., Derrer-Merk E., Oparaji B. U., Stepanov V., Clearkin L., Ferson S., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amanat F., Stadlbauer D., Strohmeier S., Nguyen T., Chromikova V., McMahon M., Jiang K., Asthagiri-Arunkumar G., Jurczyszak D., Polanco J., Bermudez-Gonzalez M., Kleiner G., Aydillo T., Miorin L., Fierer D., Lugo L. A., Milunka Kojic E., Stoever J., Liu S. T. H., Cunningham-Rundles C., Felgner P. L., Caplivski D., Garcia-Sastre A., Cheng A., Kedzierska K., Vapalahti O., Hepojoki J., Simon V., Krammer F., Moran T., “A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans” (preprint, Allergy and Immunology, 2020),, doi: 10.1101/2020.03.17.20037713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peeri N. C., Shrestha N., Rahman M. S., Zaki R., Tan Z., Bibi S., Baghbanzadeh M., Aghamohammadi N., Zhang W., Haque U., The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol, doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larremore D. B., Fosdick B. K., Bubar K. M., Zhang S., Kissler S. M., Metcalf C. J. E., Buckee C., Grad Y., medRxiv, in press, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.15.20067066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emory develops diagnostic antibody blood test to determine antibody-responses to COVID-19 (2020), (available at https://news.emory.edu/stories/2020/04/coronavirus_antibody_blood_test/index.html).

- 37.Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., Wang X., Yuan J., Li T., Li J., Qian S., Hong C., Wang F., Liu Y., Wang Z., He Q., Li Z., He B., Zhang T., Fu Y., Ge S., Liu L., Zhang J., Xia N., Zhang Z., Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis, doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang A. T., Garcia-Carreras B., Hitchings M. D. T., Yang B., Katzelnick L., Rattigan S. M., Borgert B., Moreno C., Solomon B. D., Rodriguez-Barraquer I., Lessler J., Salje H., Burke D. S., Wesolowski A., Cummings D. A. T., “A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: antibody kinetics, correlates of protection, and association of antibody responses with severity of disease” (preprint, Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS), 2020),, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.14.20065771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mossong J., Hens N., Jit M., Beutels P., Auranen K., Mikolajczyk R., Massari M., Salmaso S., Tomba G. S., Wallinga J., Heijne J., Sadkowska-Todys M., Rosinska M., Edmunds W. J., Social Contacts and Mixing Patterns Relevant to the Spread of Infectious Diseases. PLOS Medicine. 5, e74 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prem K., Cook A. R., Jit M., Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLOS Computational Biology. 13, e1005697 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cryptic transmission of novel coronavirus revealed by genomic epidemiology, (available at https://bedford.io/blog/ncov-cryptic-transmission/).

- 42.Holshue M. L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K. H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A., Diaz G., Cohn A., Fox L., Patel A., Gerber S. I., Kim L., Tong S., Lu X., Lindstrom S., Pallansch M. A., Weldon W. C., Biggs H. M., Uyeki T. M., Pillai S. K., First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 382, 929–936 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Here’s when all 50 states plan to reopen after coronavirus restrictions | TheHill, (available at https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/493717-heres-when-all-50-states-plan-to-reopen-after-coronavirus-restrictions).

- 44.Liu Y., Gayle A. A., Wilder-Smith A., Rocklöv J., The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 27 (2020), doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He X., Lau E. H. Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X., Lau Y. C., Wong J. Y., Guan Y., Tan X., Mo X., Chen Y., Liao B., Chen W., Hu F., Zhang Q., Zhong M., Wu Y., Zhao L., Zhang F., Cowling B. J., Li F., Leung G. M., Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 1–4 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rees E. M., Nightingale E. S., Jafari Y., Waterlow N., Clifford S., Pearson C. A. B., CMMID Working Group, Jombert T., Procter S. R., Knight G. M., “COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis” (preprint, Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS), 2020),, doi: 10.1101/2020.04.30.20084780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verity R., Okell L. C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Thompson H., Walker P. G. T., Fu H., Dighe A., Griffin J. T., Baguelin M., Bhatia S., Boonyasiri A., Cori A., Cucunubá Z., FitzJohn R., Gaythorpe K., Green W., Hamlet A., Hinsley W., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Riley S., van Elsland S., Volz E., Wang H., Wang Y., Xi X., Donnelly C. A., Ghani A. C., Ferguson N. M., Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 0 (2020), doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B., Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 395, 1054–1062 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U. C. Bureau, Age and Sex Composition in the United States: 2018. The United States Census Bureau, (available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/age-and-sex/2018-age-sex-composition.html). [Google Scholar]

- 50.May 2019. OES National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, (available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oessrci.htm).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.