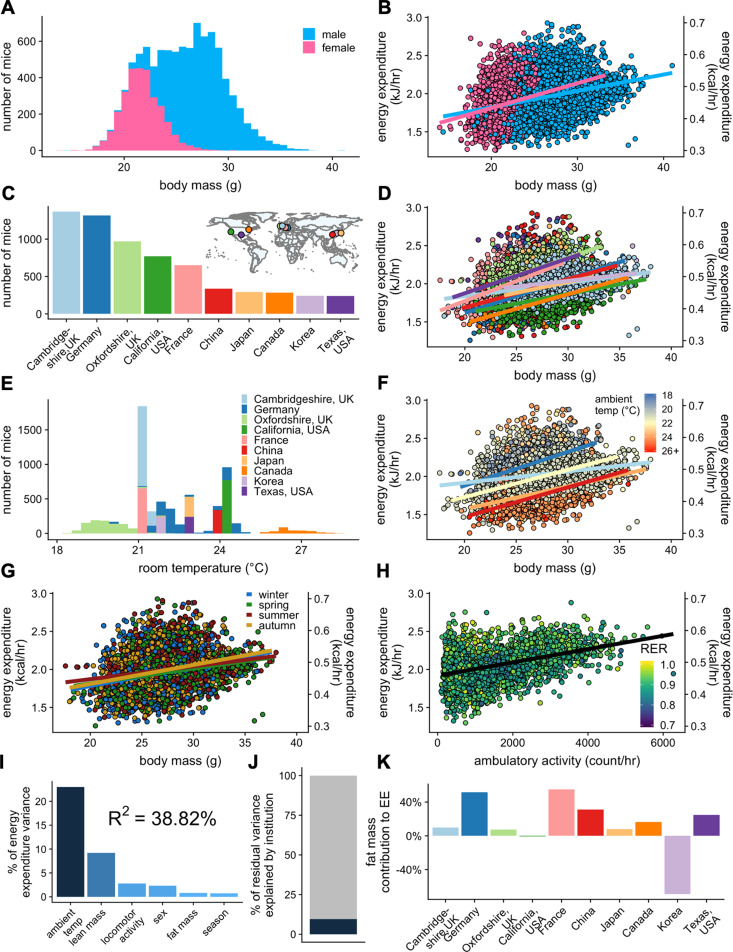

Figure 3. IMPC experiment: institutional variability of metabolic rate.

Distribution of body weights for male and female WT C57BL/6N mice from the IMPC database version 10.0 (A). Relationship of EE vs total body mass for female and male WT mice (B). The numbers of male WT mice examined at each of the 10 IMPC sites (C). Inset: geographical locations of IMPC sites. Relationship of EE vs total body mass for male WT mice at each of the 10 IMPC sites (D). Reported ambient temperatures for the experiments performed at each site (E). Relationship of EE vs total body mass in WT males for temperature (F) and season (G). Relationship of EE vs ambulatory activity in WT mice (n = 3886 males) (H). Unaccounted institutional contribution here is approximately 10% (J). The percent variation in EE explained by each of the listed factors (I). Percent contribution of fat mass to EE by site in WT males (K). n = 6469 males and 2889 females unless otherwise specified.