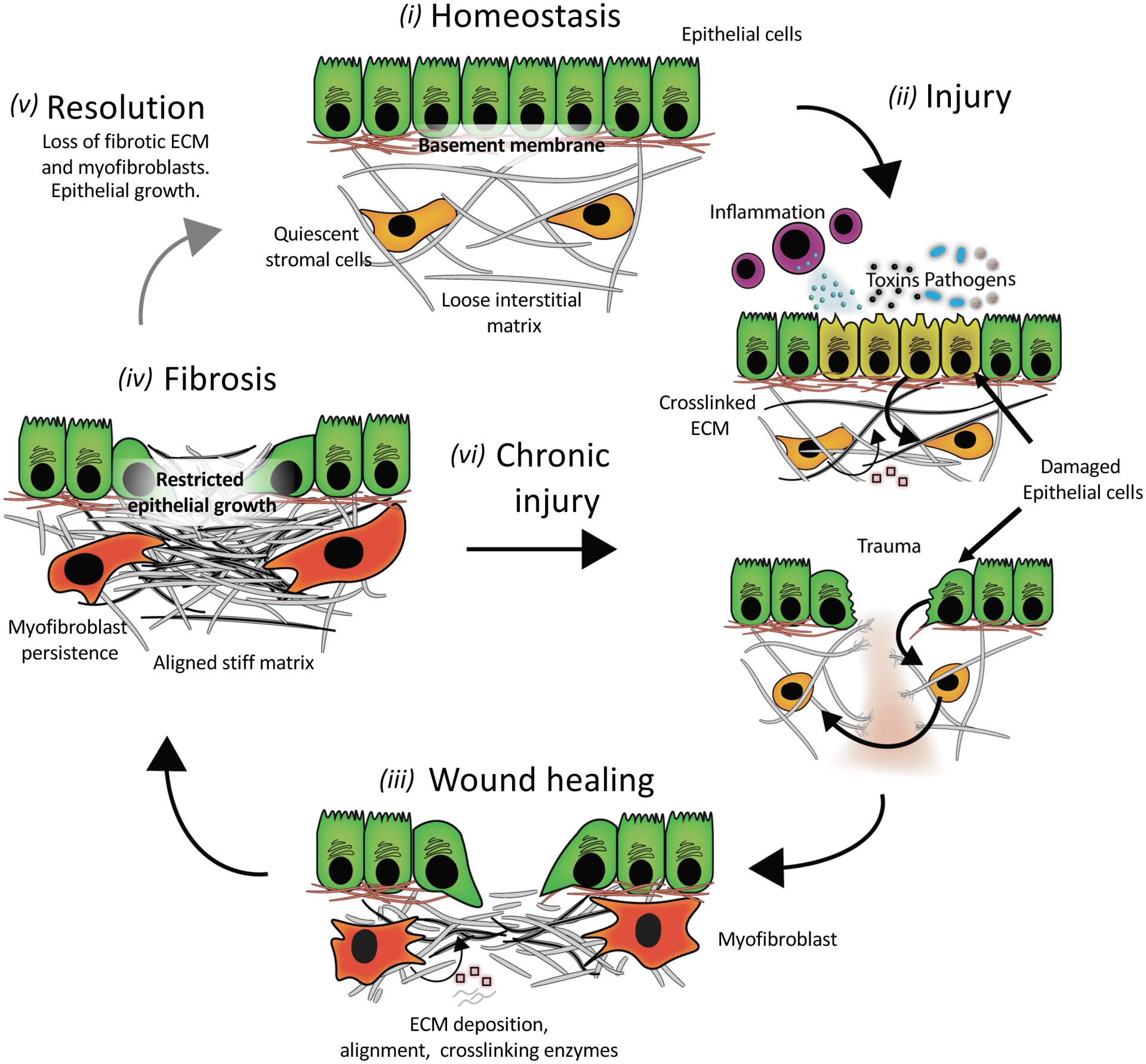

Figure 1. A simplified schematic of fibrosis pathogenesis.

(i) An ECM network in a healthy tissue has a stiffness that supports epithelial cell function and stromal cells in a quiescent state. (ii) Common injuries to tissues include trauma, autoimmune reactions (inflammation), chemicals (toxins), and pathogens (bacteria and viral infections). Acute signaling between injured epithelial and stromal cells triggers ECM remodeling (degradation and/or stiffening (pink squares are ECM modifying proteins)). (iii) During the wound-healing response, myofibroblasts secrete ECM (grey lines) and ECM-modifying proteins while also contracting the matrix to re-establish tensional homeostasis. This provisional matrix can provide a substrate for re-epithelialization; however, excessive matrix deposition and stiffening can lead to (iv) scarring or fibrosis that alters epithelial growth and differentiation. Fibrosis is marked by high levels of stiff ECM such as crosslinked collagen, with resulting myofibroblast persistence. In some tissues, fibrosis resolves (v) if the underlying stimulus for injury is removed, but often (vi) chronic injury leads to a progressive cycle of further wound healing and fibrosis without removal of excess ECM.