Abstract

Background

Rituximab (R) plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) is the current standard therapy for diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Obinutuzumab (G), a glycoengineered, type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has shown activity and an acceptable safety profile when combined with CHOP (G-CHOP) in patients with advanced DLBCL. We present the final analysis results of the Phase III GOYA study (NCT01287741), which compared the efficacy and safety of G-CHOP versus R-CHOP in patients with previously untreated DLBCL.

Methods

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with previously untreated advanced DLBCL were randomly assigned to receive eight 21-day cycles of R or G, plus six or eight cycles of CHOP. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary endpoints included overall survival, other time-to-event endpoints, and safety; investigator-assessed PFS by cell of origin subgroup was an exploratory endpoint.

Results

A total of 1418 patients were randomized, with 1414 included in this final analysis (G-CHOP, N = 704; R-CHOP, N = 710). Five-year PFS rates were 63.8% and 62.6% for G-CHOP and R-CHOP, respectively (stratified hazard ratio 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.12; p = 0.48). The results of the secondary efficacy endpoints did not show a benefit of G-CHOP over R-CHOP. In the exploratory analysis, a trend towards benefit with G-CHOP over R-CHOP was apparent in the patients with germinal center B cell DLBCL. The safety profile of G-CHOP was as expected, and no new safety signals were observed. More grade 3–5 (75.1% vs 65.8%), serious (44.4% vs 38.4%), and fatal (6.1% vs 4.4%) adverse events (AEs) were observed in the G-CHOP arm compared with the R-CHOP arm, respectively, with the most common fatal AEs being infections. A higher incidence of late-onset neutropenia occurred in the G-CHOP arm (8.7%) versus the R-CHOP arm (4.9%).

Conclusions

The final analysis, similar to the primary analysis, did not show a PFS benefit of G-CHOP over R-CHOP in previously untreated patients with DLBCL. The results of the secondary endpoints were consistent with the primary endpoint. Further exploratory analyses and investigation of biomarkers are ongoing.

Keywords: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Obinutuzumab, Rituximab, Immunochemotherapy, Outcomes

Background

Rituximab (R) in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) is the current standard of care for diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [1–3]. Despite treatment with R-CHOP, many patients’ relapse and outcomes remain poor with salvage therapies [4]. Obinutuzumab (GA101; G) is a fully humanized, glycoengineered, type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody which has shown greater direct cell death induction, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis than R [5–8].

In a Phase II study in patients with advanced DLBCL, G demonstrated promising activity and an acceptable safety profile when combined with CHOP (G-CHOP) as a first-line treatment [9]. GOYA (NCT01287741) was a randomized, open-label, multicenter Phase III study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of G-CHOP compared with R-CHOP in patients with previously untreated DLBCL. Results from the primary analysis (clinical cut-off date, 29 April 2016), which had a median observation period of 29 months, showed that G-CHOP did not significantly improve investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) compared with R-CHOP [10]. Here, we present the updated results from the final analysis of GOYA.

Methods

The study design and methodology of the GOYA study are described in full elsewhere [10]. In brief, patients were included if they were at least 18 years of age and had histologically documented, previously untreated, CD20-positive DLBCL; adequate hematologic function; ≥ 1 bi-dimensionally measurable lesion; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≤ 2; and an International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk group of high, high-intermediate, or low-intermediate risk. Low-risk patients with an IPI score of 1 (not due to age alone) or 0 with bulky disease (1 lesion ≥ 7.5 cm) were also eligible. Using stratified permuted block randomization, patients were randomized 1:1 to eight (21 days) cycles of G (1000 mg intravenous injection [IV] on days 1, 8 and 15, cycle 1 and day 1, cycles 2–8) or R (375 mg/m2 IV on day 1 of cycles 1–8) in combination with six or eight cycles of CHOP. The randomization stratification factors were number of planned cycles of CHOP, IPI score, and geographic region. Pre-planned radiotherapy was allowed for bulky or extranodal disease. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed PFS. Secondary endpoints included independent review committee (IRC)-assessed PFS (primary analysis only); overall survival (OS); complete response (CR) and overall response rate (ORR) according to the modified Cheson 2007 criteria [11] by computed tomography (CT) and CT incorporating positron emission tomography (PET); event-free survival (EFS; defined as the period from the date of randomization until the date of disease progression, relapse, initiation of a new non-protocol-specified anti-lymphoma treatment, or death from any cause); disease-free survival (DFS; defined as the percentage of patients with CR at the end of treatment); time to next anti-lymphoma treatment; and safety. An exploratory endpoint of investigator-assessed PFS according to cell of origin (COO; germinal center B cell [GCB] or activated B cell [ABC]) based on gene expression profiling using the NanoString Research-Use-Only assay (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA) [12, 13] was also analyzed.

Statistical analysis

As previously described, it was planned to enroll approximately 1400 patients over 3 years, which was expected to yield 405 PFS events for the primary analysis [10]. The final analysis was conducted once patients had completed at least 3 years of follow-up. Comparisons between treatment arms for time-to-event endpoints were performed using a stratified two-sided log-rank test (α = 0.05). The analyses stratification factors were number of planned cycles of CHOP (6 or 8) and IPI score. Kaplan–Meier analysis was also used to analyze time-to-event endpoints. Estimates of treatment effect were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression and are presented as stratified hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

A total of 1418 patients were enrolled across 207 sites in 29 countries between July 2011 and June 2014. Of these, 1414 patients were included in the final analysis (clinical cut-off date, 31 January 2018); four patients from a single study site were excluded due to serious Good Clinical Practice non-compliance. A total of 704 and 710 patients were included in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms, respectively (intent-to-treat population), with 702 and 701 receiving at least one dose of study treatment (safety population). Demographic and baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1). COO data were available for 933 patients, and the distribution of patients with each DLBCL subtype was similar between treatment arms. In total, the median time from diagnosis to randomization was 24.0 days (range, 1.0–1104.9) (G-CHOP 23.1 days [range, 3.0–1104.9]; R-CHOP: 25.0 days [range, 1.0–264.8]).

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics (intent-to-treat population)

| Characteristic | R-CHOP (N = 710) | G-CHOP (N = 704) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 62.0 (18–83) | 62.0 (18–86) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 382 (53.8) | 368 (52.3) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||

| Eastern Europe | 99 (13.9) | 97 (13.8) |

| Western Europe | 215 (30.3) | 211 (30.0) |

| Central and South America | 19 (2.7) | 13 (1.8) |

| North America | 107 (15.1) | 109 (15.5) |

| Asia | 256 (36.1) | 258 (36.6) |

| Other | 14 (2.0) | 16 (2.3) |

| ECOG PS, n (%)a | ||

| 0–1 | 611 (86.1) | 617 (87.8) |

| 2 | 99 (13.9) | 86 (12.2) |

| Ann Arbor stage, n (%)b | ||

| I and II | 171 (24.1) | 169 (24.0) |

| III and IV | 538 (75.9) | 535 (76.0) |

| IPI risk group, n (%) | ||

| Low/low-intermediate | 408 (57.5) | 374 (53.1) |

| High-intermediate | 192 (27.0) | 220 (31.3) |

| High | 110 (15.5) | 110 (15.6) |

| No. of planned CHOP cycles, n (%) | ||

| 6 | 524 (73.8) | 521 (74.0) |

| 8 | 186 (26.2) | 183 (26.0) |

| LDH elevated, n(%)c | ||

| Yes | 403 (57.1) | 415 (59.0) |

| Extranodal involvement, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 466 (65.6) | 484 (68.8) |

| Bulky disease (≥ 7.5 cm), n (%)d | 262 (37.0) | 261 (37.2) |

| Median time from diagnosis to randomization (range), dayse | 25.0 (1.0–264.8) | 23.1 (3.0–1104.9) |

| Cell of origin, n (%)f | ||

| GCB | 269 (58.2) | 271 (57.5) |

| ABC | 118 (25.5) | 125 (26.5) |

| Unclassified | 75 (16.2) | 75 (15.9) |

ABC activated B cell, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, GCB germinal center B cell, G-CHOP obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, IPI International Prognostic Index, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, R-CHOP rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

aN = 710 for R-CHOP and N = 703 for G-CHOP

bN = 709 for R-CHOP and N = 704 for G-CHOP

cN = 706 for R-CHOP and N = 703 for G-CHOP

dN = 708 for R-CHOP and N = 701 for G-CHOP

eN = 708 for R-CHOP and N = 700 for G-CHOP

fN = 462 for R-CHOP and N = 471 for G-CHOP

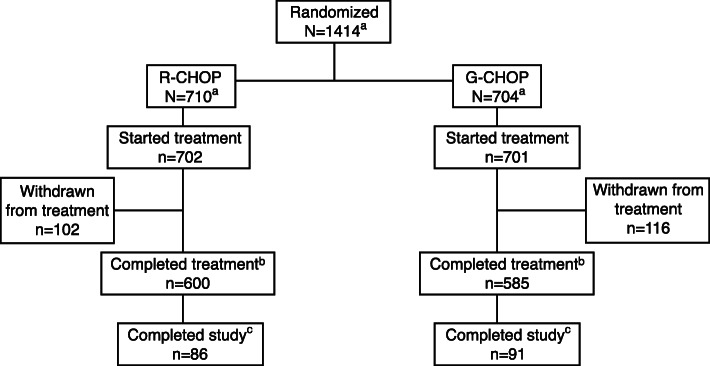

A total of 117 patients (16.7%) in the G-CHOP arm and 105 patients (15.0%) in the R-CHOP arm discontinued any component of study treatment; 116 patients (16.5%) in the G-CHOP and 102 patients (14.5%) in the R-CHOP arm discontinued antibody treatment. The most common reason for antibody treatment discontinuation was adverse events (AEs), with a higher percentage of patients in the G-CHOP arm than in the R-CHOP arm discontinuing antibody treatment due to an AE (10.4% vs 6.1%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition from the final analysis of the GOYA trial. aOverall, 1418 patients were randomized (G-CHOP arm: N = 706 and R-CHOP arm: N = 712) to the study; however, due to a serious Good Clinical Practice non-compliance at a single site, data from all 4 patients enrolled at the site (two patients in each arm) were excluded from the final analysis. bA patient was considered to have completed the treatment if they received all 8 cycles of study treatment. cThe end of the study was defined as the last patient’s last visit and occurred at approximately 6.5 years (78 months) after the first patient was enrolled to allow all patients to have ≥ 3 years of follow-up post-treatment. G-CHOP, obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

New (unplanned) anti-lymphoma treatment (including systemic new anti-lymphoma treatment, radiotherapy, or surgical procedure) was received by 113 patients (53 and 60 in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms, respectively) prior to disease progression and by 261 patients (122 and 139 in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arm, respectively) after disease progression.

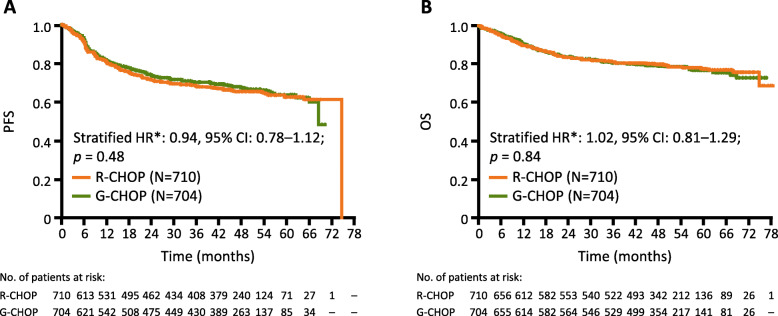

Efficacy

At the time of final analysis (median observation time, 48.0 months; range, 0.1–76.5 months for G-CHOP and 47.4 months; range, 0.1–78.2 months for R-CHOP), 224 (31.8%) patients and 233 (32.8%) patients had experienced an investigator-assessed PFS event in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms, respectively (stratified HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.12; p = 0.48) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Estimated 5-year PFS rates were 63.8% and 62.6% for G-CHOP and R-CHOP, respectively. The results of the secondary endpoints were similar between the two treatment arms (Table 2). In total, 149 (21.2%) patients in the G-CHOP arm and 145 (20.4%) patients in the R-CHOP arm had an OS event. Estimated 5-year OS rates were 77.0% and 77.7% for G-CHOP and R-CHOP, respectively (stratified HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.81–1.29; p = 0.84; Fig. 2). EFS at 5 years was 60.6% and 58.9% in the G-CHOP arm and R-CHOP arm, respectively (stratified HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.80–1.12; p = 0.53). Time to start of new anti-lymphoma treatment was similar between the two groups, with events experienced by 33.8% of patients in the G-CHOP arm and 35.2% of patients in the R-CHOP arm (stratified HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.78–1.12; p = 0.45). The proportion of patients with a CR was similar for the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms when assessed with CT incorporating PET or CT alone (56.5% vs 59.1% and 35.4% vs 33.9%, respectively). The ORR was also similar between treatment arms with CT incorporating PET or CT alone (77.1% vs 77.6% and 81.4% vs 80.1% for G-CHOP vs R-CHOP, respectively).

Table 2.

Summary of efficacy endpoints (intent-to-treat population)

| Investigator assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | R-CHOP (N = 710) | G-CHOP (N = 704) | |

| Median observation time (range), months | 47.4 (0.1–78.2) | 48.0 (0.1–76.5) | |

| Investigator-assessed PFS (primary endpoint) | |||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 233 (32.8) | 224 (31.8) | |

| 5-year PFS, % (95% CI) | 62.6 (58.1–66.8) | 63.8 (59.3–68.0) | |

| Stratified HR (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) | ||

| P (log-rank)* | P = 0.48 | ||

| OS | |||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 145 (20.4) | 149 (21.2) | |

| 5-year OS, % (95% CI) | 77.7 (74.1–80.9) | 77.0 (73.3–80.3) | |

| Stratified HR (95% CI) | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) | ||

| P (log-rank)* | P = 0.84 | ||

| DFS in patients with investigator-assessed CR | |||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 78 (19.8) | 93 (22.3) | |

| Stratified HR (95% CI)* | 1.19 (0.88–1.61) | ||

| Investigator-assessed EFS | |||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 265 (37.3) | 257 (36.5) | |

| Proportion of EFS at 5 years, % (95% CI) | 58.9 (54.5–63.1) | 60.6 (56.3–64.6) | |

| Stratified HR (95% CI) | 0.95 (0.80–1.12) | ||

| P (log-rank)* | P = 0.53 | ||

| Time to start of new anti-lymphoma treatment | |||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 250 (35.2) | 238 (33.8) | |

| Stratified HR (95% CI) | 0.93 (0.78–1.12) | ||

| P (log-rank)* | P = 0.45 | ||

| Investigator-assessed response rate (CT with PET) at end of treatmenta | R-CHOP (N= 665) | G-CHOP (N= 669) | |

| ORR | |||

| n (%) | 516 (77.6) | 516 (77.1) | |

| Percentage difference (95% CI) | − 0.46 (− 5.03–4.11) | ||

| CR rate | |||

| n (%) | 393 (59.1) | 378 (56.5) | |

| Percentage difference (95% CI) | − 2.60 (− 7.97–2.78) | ||

| Investigator-assessed response rate (CT without PET) at end of treatmenta | R-CHOP (N= 710) | G-CHOP (N= 704) | |

| ORR | |||

| n (%) | 569 (80.1) | 573 (81.4) | |

| Percentage difference (95% CI) | 1.25 (− 2.93–5.43) | ||

| CR rate | |||

| n (%) | 241 (33.9) | 249 (35.4) | |

| Percentage difference (95% CI) | 1.43 (− 3.61–6.46) | ||

CR complete response, DFS disease-free survival, EFS event-free survival, G-CHOP obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, HR hazard ratio, ORR overall response rate, OS overall survival, PET positron emission tomography, PFS progression-free survival, R-CHOP rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

*Stratification factors were International Prognostic Index and planned number of CHOP cycles (6 or 8)

aAccording to the revised response criteria

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS by treatment group and OS by treatment group. a Investigator-assessed PFS (primary endpoint) by treatment (ITT population), in which no significant difference was found for G-CHOP compared with R-CHOP. b OS by treatment (ITT population), which showed no significant difference in survival between treatment groups. *Stratified by planned number of CHOP cycles and IPI score. CI, confidence interval; G-CHOP, obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; ITT, intent-to-treat; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

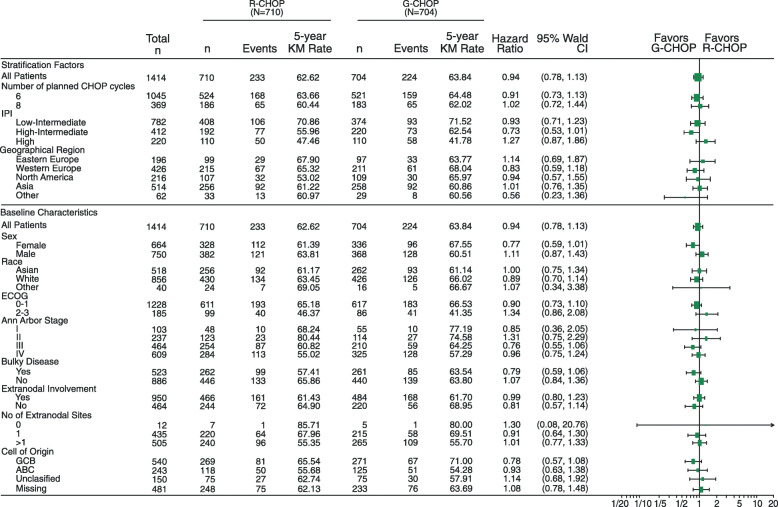

Overall, the results of the PFS subgroup analyses were consistent with PFS in the overall population with no significant difference observed between treatment arms for any subgroup according to stratification factors and baseline characteristics (Fig. 3); although, notably, patients with a high IPI score at baseline trended towards a better response to treatment with R-CHOP compared with G-CHOP (low-intermediate: HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.71–1.23; high-intermediate: HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.53–1.01; high: HR 1.27, 95% CI 0.87–1.86; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of unstratified HRs for investigator-assessed PFS by treatment group and patient subgroup. CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; G-CHOP, obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; HR, hazard ratio; IPI, International Prognostic Index; KM, Kaplan–Meier; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

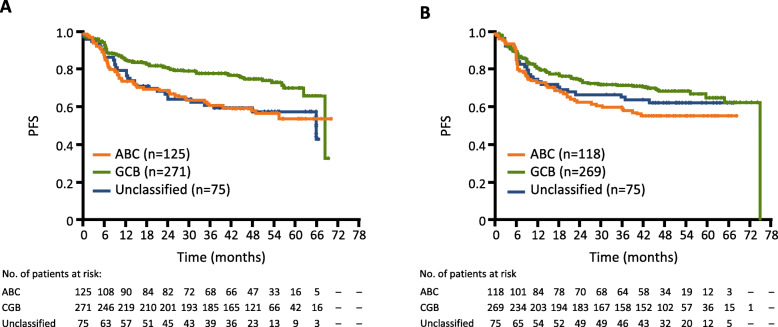

Kaplan–Meier analysis of PFS according to treatment arm in patients with different COO subtypes (ABC, GCB, and unclassified) is summarized in Fig. 4. The GCB subgroup appeared to be associated with a better PFS compared with ABC and unclassified subgroups (5-year Kaplan–Meier PFS estimates, 71.0%, 54.3%, and 57.9% in the G-CHOP arm and 65.5%, 55.7%, and 62.7% in the R-CHOP arm; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS by COO status by treatment group. a Investigator-assessed PFS by COO with G-CHOP, where GCB appeared to have a better outcome compared with ABC and unclassified subgroups. b Investigator-assessed PFS by COO with R-CHOP, where GCB also appeared to have a better outcome versus ABC and unclassified subgroups. ABC, activated B cell; COO, cell of origin; GCB, germinal center B cell; G-CHOP, obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

No significant reductions in the risk of disease progression with G-CHOP relative to R-CHOP were observed for patients with GCB, ABC, or unclassified DLBCL, although a trend towards benefit with G-CHOP compared to R-CHOP was apparent for the GCB subgroup (stratified HR, GCB 0.80, 95% CI 0.58–1.12; ABC 0.91, 95% CI 0.61–1.36; and unclassified 1.10, 95% CI 0.65–1.88; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig 1).

Safety

Safety results from the final analysis are consistent with those reported in the primary analysis, with no new safety signals. Most patients in each treatment arm (97.6% in the G-CHOP arm and 94.0% in the R-CHOP arm) experienced at least one AE (Table 3). The incidence of grade 3–5 AEs was higher in the G-CHOP arm (75.1%) compared with the R-CHOP arm (65.8%). Serious AEs were also more common in the G-CHOP arm (44.4% vs 38.4%).

Table 3.

Summary of safety (AEs by preferred term reported by ≥ 5% of patients; safety population)

| Variable | R-CHOP (N = 701) n (%) | G-CHOP (N = 702) n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of deaths (any reason) | 141 (20.1) | 149 (21.2) | ||

| No. of patients withdrawn from the study due to an AE | 4 (0.6) | 6 (0.9) | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 | ||||

| AE | 659 (94.0) | 685 (97.6) | ||

| Grade 3–5 AE | 461 (65.8) | 527 (75.1) | ||

| AE with fatal outcomea | 31 (4.4) | 43 (6.1) | ||

| Serious AE | 269 (38.4) | 312 (44.4) | ||

| Treatment-related AE | 600 (85.6) | 647 (92.2) | ||

| AE leading to withdrawal of any treatment | 58 (8.3) | 8.7 (12.4) | ||

| AE leading to dose reduction for any treatment | 142 (20.3) | 145 (20.7) | ||

| Grade 3–5 AE, n (%) | Serious AE, n (%) | Grade 3–5 AE, n (%) | Serious AE, n (%) | |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | ||||

| Neutropenia | 277 (39.5) | 38 (5.4) | 336 (47.9) | 54 (7.7) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 108 (15.4) | 71 (10.1) | 130 (18.5) | 85 (12.1) |

| Leukopenia | 78 (11.1) | – | 104 (14.8) | – |

| Anemia | 55 (7.8) | – | 53 (7.5) | – |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11 (1.6) | – | 40 (5.7) | – |

| Infections and infestations | ||||

| Pneumonia | 34 (4.9) | 33 (4.7) | 44 (6.3) | 43 (6.1) |

AE adverse event, G-CHOP obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, R-CHOP rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

aFatal AEs that occurred in more than one patient in either group, listed as preferred terms, were as follows: death (cause unknown; 2 patients in the R-CHOP arm and 3 patients in the G-CHOP arm), pneumonia (5 patients in each arm), septic shock (6 patients in the G-CHOP arm), sepsis (3 patients in the R-CHOP arm and 1 patient in the G-CHOP arm), hepatocellular carcinoma (1 patient in the R-CHOP arm and 2 patients in the G-CHOP arm), cerebrovascular accident (2 patients in each arm), and pulmonary embolism (2 patients in the G-CHOP group)

A higher number of patients in the G-CHOP arm compared with the R-CHOP arm discontinued any component of study treatment due to an AE (12.4% vs 8.3%). Fatal AEs occurred in 43 (6.1%) patients in the G-CHOP arm and 31 (4.4%) patients in the R-CHOP arm, with infections being the most common; in particular, five patients (0.7%) in each arm had a fatal case of pneumonia, and six patients (0.9%) in the G-CHOP arm versus no patients in the R-CHOP arm had a fatal case of septic shock (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the most common cause of death was disease progression (G-CHOP 12.4% and R-CHOP 13.1%).

In total, 22 (3.1%) patients in the G-CHOP arm and 26 (3.7%) patients in the R-CHOP arm had a second malignancy. The most common of these were prostate cancer (0.4% in each arm), lung adenocarcinoma (0.4% and 0.3% in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms, respectively), and breast cancer (0.1% and 0.4% in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms, respectively). Prolonged neutropenia (0.3% vs 0.0%) and late-onset neutropenia (8.7% vs 4.9%) occurred at a greater frequency in the G-CHOP arm compared with the R-CHOP arm.

Discussion

This Phase III, open-label, randomized study was designed to compare the efficacy and safety of G-CHOP versus R-CHOP in previously untreated patients with DLBCL. In agreement with the findings of the primary analysis (clinical cut-off date, 29 April 2016) [10], results of this analysis did not demonstrate superiority of G-CHOP compared to R-CHOP.

After a median observation time of 47.7 months, investigator-assessed PFS (study primary endpoint) did not differ significantly between G-CHOP and R-CHOP (stratified HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.12; p = 0.48), with similar results to those obtained in the primary analysis (stratified HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.11; p = 0.39). The results of the secondary endpoints were consistent with the primary endpoint and did not show a benefit of G-CHOP over R-CHOP. The 5-year OS rates were similar for G-CHOP and R-CHOP (77.0% vs 77.7%).

G-chemotherapy has previously demonstrated superiority compared with R-chemotherapy in studies of patients with other B cell malignancies, such as follicular lymphoma (FL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [14, 15]. The lack of superior efficacy of G-CHOP compared with R-CHOP observed within this study was unexpected.

In the present study, we noted a trend towards a PFS benefit with G-CHOP versus R-CHOP in patients with GCB DLBCL. Like FL, GCB DLBCL is derived from germinal center B cells, and many driver genetic alterations that provide a selective advantage and contribute to cancer development are seen in both lymphomas [16]. This may, in part, explain the trend in benefit observed in the patients with GCB DLBCL, which is consistent with the improvement in outcome seen in patients with FL when treated with G-CHOP versus R-CHOP [14]. Interestingly, we found that the ABC DLBCL subgroup was associated with better PFS (5-year Kaplan–Meier PFS estimates: G-CHOP 54.3% and R-CHOP 55.7%) than reported in retrospective population analyses of previously untreated patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP (5-year Kaplan–Meier PFS estimates: R-CHOP 46% [17] and 48% [18]). This result may indicate a selection bias for low-risk patients in the GOYA trial, with very high-risk patients requiring urgent treatment less likely to be enrolled into a prospective trial such as this. It is noteworthy that the total median time from diagnosis to randomization was 24.0 days (range, 1.0–1104.9). While it is unclear how selection bias may have affected the overall result, there was no significant improvement in outcome with G-CHOP in any IPI subgroup.

The frequency and nature of the AEs reported were as expected for the patient population and the treatment regimens being assessed, and no new safety signals were observed during the additional follow-up after the primary analysis. Higher rates of grades 3–5 and serious AEs occurred in the G-CHOP arm compared with the R-CHOP arm; however, these were generally clinically manageable. A similar percentage of deaths occurred in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms (21.2% vs 20.1%), and the majority of these fatalities were due to disease progression (12.4% vs 13.1%). There were no unexpected delayed toxicities observed, and a similar number of second malignancies occurred in the G-CHOP and R-CHOP arms (3.1 and 3.7%, respectively). A higher frequency of late-onset neutropenia was observed in the G-CHOP arm compared with the R-CHOP arm (8.7% vs 4.9%, respectively).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the final analysis of this study demonstrated that G-CHOP did not show a PFS benefit over R-CHOP in previously untreated patients with DLBCL, and R-CHOP remains the standard of care in this population. The results of the secondary endpoints were consistent with the primary endpoint. Overall, no unexpected safety findings were observed, and the toxicity of G-CHOP was generally manageable. Exploratory analyses and investigations of biomarkers are ongoing to evaluate whether there may be a role for G in identifiable subgroups of DLBCL.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Grade 5 (fatal) adverse events (safety evaluable population). Supplementary Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS by treatment group for COO subtypes. A Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the GCB subgroup, in which a trend towards a better PFS with G-CHOP was observed; B Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the ABC subgroup, where no difference in PFS between treatment arms was observed; C Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the unclassified subgroup, in which there was also no difference in PFS between treatment arms.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge David Belada, John M. Burke, Angelo Michele Carella, Olivier Catalani, Neil Chua, Pau Abrisqueta, Judit Demeter, Gunter Fingerle-Rowson, Ian Flinn, Xiaonan Hong, Won Seog Kim, Mikkel Z. Oestergaard, Antonio Pinto, Yuan-Kai Shi, Yoichi Tatsumi, and Michael Wenger for their contribution to the GOYA study design, conduct, and analysis. Third-party medical writing assistance, under the direction of Laurie Sehn, was provided by Zoe Toland and Katie Smith of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, and was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Activated B cell

- AE

Adverse event

- CHOP

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

- CI

Confidence interval

- COO

Cell of origin

- CR

Complete response

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DLBCL

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EFS

Event-free survival

- FL

Follicular lymphoma

- GCB

Germinal center B cell

- G

Obinutuzumab

- G-CHOP

Obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

- G-CSF

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IPI

International Prognostic Index

- IRC

Independent review committee

- IV

Intravenous

- KM

Kaplan–Meier

- ORR

Overall response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- R

Rituximab

- R-CHOP

Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: Laurie H. Sehn, Maurizio Martelli, Marek Trněný, Umberto Vitolo. Provision of study materials or patients: Laurie H. Sehn, Maurizio Martelli, Marek Trněný, and Umberto Vitolo. Collection and assembly of data: Marek Trněný. Data analysis and interpretation: all authors. Manuscript writing: all authors. Final approval of manuscript: all authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Funding

GOYA was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd with the scientific support of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi.

Availability of data and materials

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient level data through the clinical study data request platform (https://vivli.org/). Further details on Roche's criteria for eligible studies are available here (https://vivli.org/members/ourmembers/). For further details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here (https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

Approval from the Independent Review Board (IRB)/Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) was obtained before the start of the study, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

C.B is employed by Genentech, Inc. and has equity ownership interests (including stock options) in F. Hoffmann-La Roche. A.K and W.L are employed by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. M.M has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Celgene, Janssen, Sandoz, Novartis, Gilead, and Servier and is a member of an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees for F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Celgene, Janssen, Sandoz, Novartis, and Gilead. D.S and G.S are employed by and have equity ownership interests (including stock options) for F. Hoffmann-La Roche. L.S has provided consultancy (including expert testimony) for F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Inc., AbbVie, Amgen, Apobiologix, AstraZeneca, Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, Karyopharm, Lundbeck, Merck, Morphosys, Seattle Genetics, Teva, Takeda, TG Therapeutics, Verastem; has received research funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Genentech, Inc.; and has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Inc., AbbVie, Amgen, Apobiologix, AstraZeneca, Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, Karyopharm, Lundbeck, Merck, MorphoSys, Seattle Genetics, Teva, Takeda, TG Therapeutics, Verastem. M.T provides consultancy (including expert testimony) for Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, AbbVie, Amgen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Celgene, and MorphoSys and has received honoraria from Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, AbbVie, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, MorphoSys, and Incyte. U.V is part of the speaker’s bureau for Celgene, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Gilead, AbbVie, and Novartis and a member of advisory committees for Janssen, Celgene, Kite, Juno Therapeutics, Gilead, and Novartis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13045-020-00900-7.

References

- 1.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-Cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilly H, Gomes da Silva M, Vitolo U, Jack A, Meignan M, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v116–v125. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in oncology: B-Cell Lymphomas, version 7. 2019 [Accessed 16 January 2020]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf.

- 4.Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: optimizing outcome in the context of clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Blood. 2015;125(1):22–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herter S, Herting F, Mundigl O, Waldhauer I, Weinzierl T, Fauti T, et al. Preclinical activity of the type II CD20 antibody GA101 (obinutuzumab) compared with rituximab and ofatumumab in vitro and in xenograft models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(10):2031–2042. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mossner E, Brunker P, Moser S, Puntener U, Schmidt C, Herter S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. 2010;115(22):4393–4402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morschhauser FA, Cartron G, Thieblemont C, Solal-Celigny P, Haioun C, Bouabdallah R, et al. Obinutuzumab (GA101) monotherapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large b-cell lymphoma or mantle-cell lymphoma: results from the phase II GAUGUIN study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2912–2919. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golay J, Da Roit F, Bologna L, Ferrara C, Leusen JH, Rambaldi A, et al. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood. 2013;122(20):3482–3491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharman JP, Forero-Torres A, Costa LJ, Flinn IW, Inhorn L, Kelly K, et al. Obinutuzumab plus CHOP is effective and has a tolerable safety profile in previously untreated, advanced diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the phase II GATHER study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(4):894–903. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1515940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitolo U, Trněný M, Belada D, Burke JM, Carella AM, Chua N, et al. Obinutuzumab or rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3529–3537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott DW, Wright GW, Williams PM, Lih CJ, Walsh W, Jaffe ES, et al. Determining cell-of-origin subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using gene expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Blood. 2014;123(8):1214–1217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-536433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallden B, Ferree S, Ravi H, Dowidar N, Hood T, Danaher P, et al. Development of the molecular diagnostic (MDx) DLBCL Lymphoma Subtyping Test (LST) on the nCounter Analysis System. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_suppl):8536. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.8536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, Klapper W, Opat S, Owen C, et al. Obinutuzumab for the first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1331–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, Engelke A, Eichhorst B, Wendtner CM, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pon JR, Marra MA. Clinical impact of molecular features in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2016;127(2):181–186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-658401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ennishi D, Mottok A, Ben-Neriah S, Shulha HP, Farinha P, Chan FC, et al. Genetic profiling of MYC and BCL2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma determines cell-of-origin-specific clinical impact. Blood. 2017;129(20):2760–2770. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-747022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott DW, Mottok A, Ennishi D, Wright GW, Farinha P, Ben-Neriah S, et al. Prognostic significance of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell of origin determined by digital gene expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue biopsies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(26):2848–2856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Grade 5 (fatal) adverse events (safety evaluable population). Supplementary Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS by treatment group for COO subtypes. A Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the GCB subgroup, in which a trend towards a better PFS with G-CHOP was observed; B Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the ABC subgroup, where no difference in PFS between treatment arms was observed; C Investigator-assessed PFS by treatment arm in the unclassified subgroup, in which there was also no difference in PFS between treatment arms.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient level data through the clinical study data request platform (https://vivli.org/). Further details on Roche's criteria for eligible studies are available here (https://vivli.org/members/ourmembers/). For further details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here (https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm).