Abstract

Background

Patient adherence to treatment is a key determinant of outcome for healthcare interventions. Whilst non-adherence has been well evidenced in settings such as drug therapy, information regarding patient adherence to orthoses, particularly in the acute setting, is lacking. The aim of this systematic review was to identify, summarise, and critically appraise reported methods for assessing adherence to removable orthoses in adults following acute injury or surgery.

Methods

Comprehensive searches of the Ovid versions of MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, Central, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and SPORTDiscus identified complete papers published in English between 1990 and September 2018 reporting measurement of adherence to orthoses in adults following surgery or trauma to the appendicular skeleton. Only primary studies with reference to adherence in the title/abstract were included to maintain the focus of the review. Data extraction included study design, sample size, study population, orthosis studied, and instructions for use. Details of methods for assessing adherence were extracted, including instrument/method used, frequency of completion, number of items (if applicable), and score (if any) used to evaluate adherence overall. Validity and reliability of identified methods were assessed together with any conclusions drawn between adherence and outcomes in the study.

Results

Seventeen papers (5 randomised trials, 10 cohort studies, and 2 case series) were included covering upper (n = 13) and lower (n = 4) limb conditions. A variety of methods for assessing adherence were identified, including questionnaires (n = 10) with single (n = 3) or multiple items (n = 7), home diaries (n = 4), and discussions with the patient (n = 3). There was no consistency in the target behaviour assessed or in the timing or frequency of assessment or the scoring systems used. None of the measures was validated for use in the target population.

Conclusions

Measurement and reporting of adherence to orthosis use is currently inconsistent. Further research is required to develop a measurement tool that provides a rigorous and reproducible assessment of adherence in this acute population.

Trial registration

PROSPERO: CRD42016048462. Registered on 17/10/2016.

Keywords: Systematic review, Adherence, Orthoses, Appendicular skeleton, Orthopaedics

Background

Adherence to treatment, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ’the extent to which a person’s behaviour corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider’ [1], is a key determinant of healthcare outcomes. Within a clinical setting, accurate documentation of adherence aids a clinician’s judgement of whether poor adherence or ineffectiveness of a prescribed intervention may be responsible for a patient’s clinical progress. Similarly, within a research setting, measuring adherence to a specific intervention is crucial in accurately determining its efficacy and in understanding how this may affect its effectiveness in clinical practice [2]. Even the most efficacious interventions are only as effective as the degree to which patients comply with the recommendations of healthcare professionals [3, 4]. For this reason, the WHO have identified improving patient adherence as one of their key research priorities [1].

Reasons for non-adherence to medical guidance are multi-faceted, with socioeconomic, health-care system-related, condition-related, treatment-related, and patient-related factors all contributing [1]. With regard to orthosis use, specific factors such as discomfort, ill fit, inconvenience, skin irritation, and issues such as disturbed sleep have all been postulated as reasons for non-adherence [5–8]. Although not a straightforward relationship, there is evidence to support that adherence to the prescribed use of an orthosis in acute conditions leads to superior outcomes following muscle tears [9] and tendon injuries [10–12] and post-operatively [13].

Measuring adherence is a complex task. There are multiple definitions of the term, it can fluctuate over time, and simply measuring adherence can influence the behaviour itself [14]. Accurately and reliably measuring adherence becomes more difficult with interventions that rely on the co-operation and engagement of patients away from direct supervision of healthcare professionals. The use of removable orthoses is an ideal example of this, as these devices are often prescribed with complex treatment protocols to be followed at home.

Systematic reviews have previously described and appraised the measurement tools used for assessing adherence in home-based exercise programmes [15–17] and in medication adherence [18], but to our knowledge none exist in patients prescribed removable orthoses.

The aim of this review was to identify, summarise, and critically appraise the methods reported in the literature for assessing patient adherence to treatment with a removable orthosis in adults following surgery or trauma to the appendicular skeleton. This review formed part of the MALIT (Mallet Injury Trial) study, preliminary work to inform the design of a future randomised controlled trial (RCT) in mallet injury splinting, to identify candidate measures of adherence for use in a future trial.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (reference number CRD42016048462) prior to commencing data extraction.

Literature search strategy

The Ovid search platform (OvidSP) versions of MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Central, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and SPORTDiscus were searched using a search strategy developed by members of the team in consultation with a research librarian trained in healthcare research methodology. The search strategy included terms for ‘orthoses’ combined using the operator OR including ‘splints/; splint* in title/abstract; braces/; brace* in title/abstract; orthopaedic equipment/; orthotic devices/; orthos#s in title/abstract; orthotic in title/abstract; ‘appendicular skeleton’ (hand, arm, leg, finger) and ‘injury’ combined using the operator ‘AND’. Details of the search strategy are included in Additional file 1.

The search was limited to human studies, in adults, published in English from 1990 to September 2018. Studies published prior to 1990 were excluded, as they were unlikely to reflect current practice. Abstracts and conference reports were not included due to difficulties evaluating incomplete information. Systematic reviews and qualitative research were excluded, as they did not present methods for the assessment of patient adherence. Study protocols were excluded due to lack of information on how adherence impacted on outcome.

Duplicate records were excluded, and the titles and abstracts of the remaining citations were independently screened by two reviewers (ZT, DY, or GD) using a standardised online screening pro forma, with an additional 5% screened at random by a third investigator (JH) to validate the screening process. The reference lists of retrieved articles and identified reviews were manually searched to identify additional potentially relevant studies. Full text articles were obtained for all potentially eligible records, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion (ZT, JMB, and JH).

Selection of papers

To specifically focus on methods for assessing adherence, only papers including mention of ‘adherence’ in the title or abstract were included in the review.

RCTs, observational studies (prospective and retrospective), and case studies/series were eligible for inclusion if they assessed adherence to a removable orthosis in adult patients aged 18 and older following an acute injury or surgery. For the purposes of the review, the removable orthosis was required to fulfil the following criteria: (1) removable by the patient, (2) applied to a part of the appendicular skeleton, (3) immobilising or partially immobilising, e.g. allowing movement in one plane of motion, or allowing restricted movement for rehabilitation exercises, and (4) used following surgery or trauma. Studies on patients requiring orthoses for chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis were excluded to focus the review on adherence in acute conditions.

Papers were screened for inclusion independently by two reviewers (ZT, DY, or GD) using a standardised inclusion criteria pro forma. Uncertainties that remained after full text review were resolved by discussion with the study team (JH, SP, JMB).

Data extraction

Study demographics

Data were extracted using a standardised data extraction pro forma developed by the study team (ZT and JMB). Data extracted included (1) study design (RCTs, observational studies, and case series); (2) retrospective or prospective accrual of data; (3) study population and sample size; (4) condition evaluated; (5) details of the orthoses used; (6) duration of immobilisation.

Adherence measures

Included studies were further evaluated by considering details of the methods used for assessing adherence. These were classified as (1) questionnaire based, (2) diary based, (3) interview/consultation based, or (4) not stated (if no additional details were given). Details including instructions given regarding completion, timing of completion, the mode of completion (self-report, health professional administered, not stated), and frequency of assessment were extracted. For questionnaire-based studies, further information regarding the number and content of items in each instrument, the aspects of adherence assessed, and any scoring system used was also extracted.

The measures used were critically appraised to determine validity and reliability. This included details of whether the instruments used were validated or had been used in previous studies, and the risk of response bias. The risk of response bias in each assessment was evaluated as (1) high if the instrument/interview was conducted by the clinician involved in the patient’s care, (2) medium if the questionnaire was patient-reported but administered directly by a member of the clinical team, (3) low if the instrument was a self-administered questionnaire or consultation with a health professional unrelated to the study team, and (4) indeterminate if there were insufficient details given.

Finally, any details were extracted regarding whether the studies included any report of the association between adherence and outcome. As the aim of this review was to explore methods for assessing adherence, risk of bias within the individual studies themselves was not assessed.

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (ZT, GD) with a third reviewer (JH) independently extracting approximately 30% for data validation purposes. Where there was uncertainty, this was discussed with JMB.

Data analysis

Data were tabulated and details of assessment methods compared.

Results

Literature search and study selection

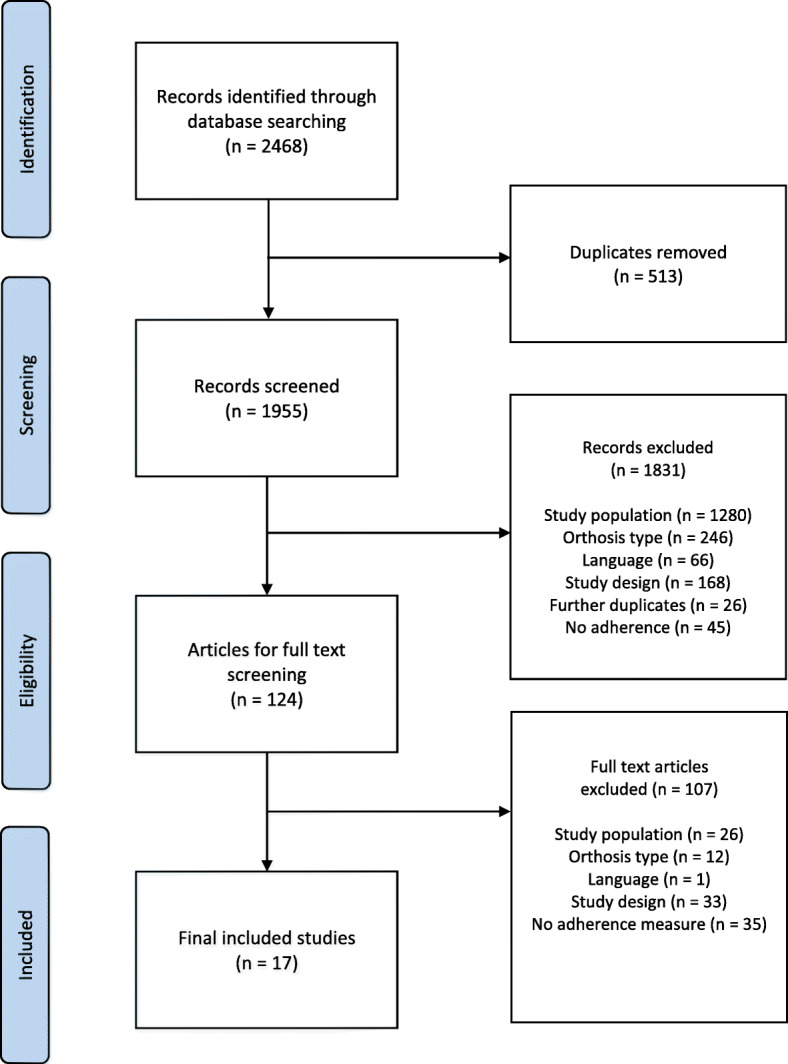

From 1955 citations, 124 articles were obtained for full text screen and 14 systematic reviews for reference list screening (Fig. 1). The interrater reliability for title and abstract screening was 97%. Only 3% had discrepancies, which were resolved by full text screening. Some 17 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies

Study design

The 17 studies included five RCTs [11, 19–22], eight prospective cohort studies [9, 12, 13, 23–27], two retrospective cohort studies [10, 28], and two individual patient case reports [29, 30]. Seven (41%) studies were single centre; 8 (47%) were undertaken in North America. The median sample size was 64 (range 1–188) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Number of studies | |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| RCT | 5 |

| Cohort | 10 |

| Case series | 2 |

| Data collection | |

| Prospective | 13 |

| Retrospective | 4 |

| Number of centres | |

| Single-centre | 7 |

| Multi-centre | 6 |

| Unclear | 4 |

| Country | |

| UK | 2 |

| Europe | 3 |

| North America | 8 |

| Asia | 3 |

| Australasia | 1 |

| Sample size | |

| Median | 64 |

| Range | 1–188 |

| Anatomical location | |

| Shoulder | 5 |

| Hand/wrist | 8 |

| Knee | 2 |

| Foot/ankle | 2 |

The study populations included orthoses applied to the upper (hand [10–13, 25, 29], forearm [24, 28], shoulder [9, 19, 20, 22, 27]) and lower (knee [21, 26], ankle [23], foot [30]) limb. Details of the studies included in the analysis are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details of included studies

| Author + year | Study design | No. of centres | Country | Sample size (no. of patients) | Medical condition | Type of orthosis | Instructions for daily use | Method of instruction | Duration of immobilisation | Adherence measure(s) used | Risk of bias in assessment of adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuff 2012 [9] | Prospective cohort | Unclear | USA | 92 | Post-op rotator cuff repair | Shoulder immobiliser | Removal only for exercise, bathing, dressing | Verbal | 6 weeks | Single-item questionnaire + recorded therapy attendance | Low (objective assessment) |

| Groth 1994 [10] | Retrospective cohort | Multi-centre | USA | 44 | Acute mallet finger injury | Finger splint | Removal only for finger hygiene | Verbal | Between 6 and 8 weeks | Multi-item questionnaire + therapist observation + recorded therapy attendance | Indeterminate (insufficient information) |

| Guillodo 2011 [23] | Prospective cohort | Multi-centre | France | 111 | Sprained ankle | Aircast semi-rigid ankle brace | Not reported | Not reported | Between 5 and 6 weeks | Multi-item questionnaire | Low (independent assessor) |

| Itoi 2013 [19] | Randomised controlled trial | Multi-centre | Japan | 109 | Traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation | Shoulder immobiliser | Removal only for bathing | Verbal | 3 weeks | Unclear | Indeterminate (insufficient information) |

| Liavaag 2011 [20] | Randomised controlled trial | Multi-centre | Norway | 188 | Traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation | Shoulder immobiliser | Removal only for sleeping, bathing, dressing | Verbal + written | 3 weeks | Home diary | Low (independent patient report) |

| McGrath 2008 [24] | Prospective cohort | Unclear | USA | 47 | Wrist stiffness post-trauma/surgery | Adjustable wrist brace | Worn intermittently dependent on progress | Verbal | Dependent on progress (mean 10 weeks) | Discussion with patient | Indeterminate (insufficient information) |

| Midgley 2011 [25] | Prospective cohort | Single-centre | UK | 50 | Metacarpal fracture | Hand splint | Not reported | Written | 4 weeks | Multi-item questionnaire | Low (independent assessor) |

| O’Brien 2011 [11] | Randomised controlled trial | Multi-centre | Australia | 64 | Acute mallet finger injury | Finger splint | Removal only for finger hygiene | Written | 8 weeks | Home diary + therapist observation + recorded therapy attendance | Low (independent patient report) |

| Rives 1992 [13] | Prospective cohort | Unclear | USA | 23 | Surgically managed proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) contraction | Finger splint | Worn continuously | Verbal | 6 months | Discussion with patient | High (patient + clinician discussion) |

| Rankin 2000 [26] | Prospective cohort | Unclear | Canada | 77 | Post-op anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction | Knee brace | Worn during high-risk sports | Not reported | 6–18 months | Multi-item questionnaire | Low (postal questionnaire) |

| Roh 2016 [12] | Prospective cohort | Single-centre | South Korea | 72 | Acute mallet finger injury | Finger splint | Removal only for finger hygiene | Written | 7 weeks | Single-item questionnaire | Low (independent assessor) |

| Sandford 2008 [28] | Retrospective cohort | Single-centre | UK | 80 | Post-op flexor/extensor tendon repair | Long forearm splint | Worn continuously | Not reported | 4 weeks | Multi-item questionnaire | Low (independent patient report) |

| Silverio 2014 [27] | Prospective cohort | Single-centre | USA | 50 | Post-op rotator cuff repair | Shoulder immobiliser | Removal only for exercise, bathing, dressing | Verbal | 6 weeks | Multi-item questionnaire | Medium (questionnaire given by clinician at follow-up) |

| Swirtun 2005 [21] | Randomised controlled trial | Single-centre | Sweden | 95 | ACL rupture (conservative management) | Knee brace | Worn during all daytime activities | Verbal | 12 weeks | Single-item questionnaire | Indeterminate (insufficient information) |

| Whelan 2014 [22] | Randomised controlled trial | Multi-centre | Canada | 60 | Traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation | Shoulder immobiliser | Removal only for exercise, bathing, dressing | Written | 4 weeks | Home diary + multi-item questionnaire | Low (independent patient report) |

| Wollstein 2012 [29] | Case report | Single-centre | USA | 1 | PIPJ contracture | Finger splint | Not reported | Not reported | 12 weeks | Home diary | Indeterminate (insufficient information) |

| Yang 2011 [30] | Case report | Single-centre | Taiwan | 1 | Lisfranc injury | Foot brace | Not reported | Not reported | Unclear | Discussion with patient | High (patient + clinician discussion) |

Adherence measures

The methods used to assess adherence varied widely between studies. Ten (59%) used questionnaires, four (24%) used patient-reported diaries completed at home, three (18%) involved a patient discussion, and in one study the method used was unclear. Other stated methods for assessing adherence included recorded therapy attendance (n = 3, 18%) and therapist observation of study participants (n = 2, 12%). Most studies (n = 13/17, 76%) relied on a single measure of adherence, whilst four (two RCTs [11, 22] and two cohort studies [9, 10]) assessed adherence using a combination of measures. Studies using more than one method did not differ greatly from the remaining studies in terms of sample size or geographical location, but three of the four studies were multi-centre, and all involved orthoses applied to the upper limb. Eight studies (47%) used methods for assessing adherence that were at low risk of bias, as they were completed independently of the clinicians delivering patient care. The remaining methods were either at high risk of bias or insufficient detail was provided for an assessment to be made. None of the included studies used an adherence measure that had been validated for use in this patient group. None of the studies reported patient or staff feedback regarding the adherence methods used.

Patient questionnaires

Ten studies used patient questionnaires to assess adherence. The majority utilised multi-item questionnaires, but three studies used single-item measures.

Single-item questionnaires

Of the three single-item measures, two were patient self-reported and one used clinician assessment. All measures were study-specific. There was a lack of consistency in the target behaviour recorded and in the way the adherence scores were determined. Whilst two studies focussed on total orthosis usage, the third recorded instances when the orthosis was removed. The method of deriving an adherence score varied from a percentage of orthosis use, to a 3-point scale of compliance, to a dichotomous (compliant vs non-compliant) method (Table 3). None of the instruments was reported to be validated, and only one study [12] used a referenced adherence score. This study used a modified version of the Groth et al. [10] 3-point scoring system that divides patients into compliant, secondary compliant, and non-compliant, although there is very limited information on the development of this tool, and the validity of the classification system is limited.

Table 3.

Single-item questionnaire information

| Study name | Assessor | Method of questionnaire administration | Validated tool? | Timing of assessment | Description of measure | Adherence score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target behaviour | Response type | ||||||

| Swirtun 2005 [21] | Patient | ‘Paper’ no other details provided | No | Weeks 8 & 12 post-injury | Daily usage of brace | Percentage of daily activities brace used (ordinal): 0–25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, 76–99%, 100% | Percentage in each group |

| Cuff 2012 [9] | Clinician | Unclear | No |

Days 1, 2, 3 (home visit) Clinic at 1, 3, 6 weeks |

Wearing brace | Dichotomous: Yes/No | Non-compliant: 1+ non-compliant event recorded |

| Roh 2016 [12] | Patient | Unclear | No | Week 7 post-injury (at splint removal) | Splint removal | Ordinal: 3 = never removed (or only with extreme care), 2 = accidentally dislodged or loose but instantly replaced, 1 = not worn properly or removed several times |

3: Compliant 2: Secondary compliant 1: Non-compliant |

Multi-item questionnaires

Multi-item questionnaires were used in almost half of the included studies (7/17; 41%). These were patient self-report questionnaires completed by patients in person in clinic (n = 2) or distributed by post (n = 1), and questionnaires administered by telephone (n = 2). The mode of questionnaire administration was unclear in the remaining two studies (Table 4). Three studies [23, 27, 28] included a copy of their study questionnaire in the final publication. As with the single-item measures, there was a lack of consistency in the target behaviours assessed, the timing of assessment, and the use of ‘adherence scores’. Some tools focussed on total orthosis use, whilst others recorded specific instances of orthosis removal (Table 4). Three of the seven studies using multi-item measures formed a combined adherence score used for analysis, whilst the others considered each of the items separately. There was also significant variation in the timing of the adherence assessment, ranging from 4 weeks to 36 months.

Table 4.

Multi-item questionnaire information

| Study name | Assessor | Method of questionnaire administration | Validated tool? | Timing of assessment | Description of measure | Adherence score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of items | Target behaviour | Response type | Combined score? | Description | |||||

| Groth 1994 [10] | Patient | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 2 |

1. Use of splint as prescribed 2. Adherence to exercise programme |

Dichotomous: Yes/No | Yes | Adherent = Yes to both |

| Guillodo 2011 [23] | Patient | Telephone call | No | 60–90 days post-injury | 2 |

1. Use of brace 2. Length of use (total days) |

1. Dichotomous Yes/No 2. Continuous: no. of days |

No | Reported individually |

| Midgley 2011 [25] | Patient | Telephone call | No | Min 10 weeks post-injury | 2 |

1. Compliance with splint use (subjective) 2. Length of use (total weeks) |

1. Dichotomous Yes/No 2. Continuous: no. of weeks |

No | Reported individually |

| Rankin 2000 [26] | Patient | Postal questionnaire | Pre-tested, not validated | 12–36 months post-reconstruction | 16 |

1. Compliance with splint use during different sports 2. Compliance with home exercise programme |

Continuous: visual analogue scale (100-mm line) | No | Reported individually |

| Sandford 2008 [28] | Patient | Paper questionnaire | No | Clinic appt 4 w post-surgery | 4 |

1. Has splint been removed? 2. Frequency of removal 3. Duration of removal 4. Reasons for removal |

1. Dichotomous: Yes/No 2. Ordinal: never, once, 2–6 times, daily 3. Ordinal: < 1 h, > 1 h 4. Descriptive |

No | Reported individually |

| Silverio 2014 [27] | Patient | Paper questionnaire | Not in this population | Clinic appt 6 w post-surgery | 4 |

1. Daily hours without sling 2. Days per week without sling 3. Why was sling removed? 4. Subjective adherence |

1. Continuous 2. Continuous 3. Nominal 4. Scale of 1–10 |

Yes | Adherence (%) = 100 x [(hours of sling use/ 24 × 0.5) + (% activities performed with sling on × 0.25) + (self-ranked adherence/ 10 × 0.25)] |

| Whelan 2014 [22] | Patient | Unclear | No | After 4 w of immobilisation | 2 |

1. Was brace used full time? 2. Was brace used for whole (4-w) period? |

Not reported | Yes | Compliant = full time use for at least 75% (3 w out of 4) of immobilisation period |

h hours, w weeks

None of the multi-item questionnaires identified had been validated for use in this population. Silverio and Cheung [27] adapted a previously published medical adherence measure [31] originally developed for use in a paediatric population. No information, however, was provided on how the adaptations (e.g. question wording, response options, scoring system) were made, or whether the adapted version had been validated in an adult population.

Another measure used by Rankin et al. [26] was reported as being developed by four surgeons and four physical therapists and subsequently pre-tested on six patients before use. However, this pre-testing only assessed simplicity and ease of completion and did not provide any additional data on the measurement properties.

Home diaries

A total of four studies used home diaries to assess adherence. All home diaries were patient-completed, but there was no consistency in the frequency of information recording, items assessed, and how individual patient adherence was scored (Table 5). Some diaries involved daily recording of hours of orthosis usage, whilst others focussed only on instances of orthosis removal. One diary involved a fortnightly recall of average daily hours of orthosis use in the preceding 2 weeks. These differences are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Home diary information

| Study name | Frequency of information recording | Instructions for adherence information recording | What information was recorded | Adherence score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liavaag 2011 [20] | Daily |

Total duration of use (days) + daily duration of immobilisation (hours) 1. No use 2. < 8 h 3. 8–16 h 4. > 16 h |

Total no. of days used + hours per day: 0 h, < 8 h, 8–16 h, > 16 h | Compliant = > 16 h for 20 + days (otherwise non-compliant) |

| O’Brien 2011 [11] | As needed | Any instances of splint removal, modification, dislodgement | Time/date of incident + reason for incident |

• Compliant: never removed (or only with extreme care) • secondary compliant: splint dislodged/loose but instantly replaced • Non-compliant: splint not worn properly/removed multiple times |

| Whelan 2014 [22] | As needed | Brace/sling usage + attendance at physical therapy | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wollstein 2012 [29] | Fortnightly | Average daily splint wear (hours) | No. of hours | No adherence score |

h hours

One study [11] used a modified version of the Groth et al. [10] 3-point scoring system, again without evidence of validation.

Interview/consultation-based methods

Three studies used unstructured discussions between clinician and patient to assess adherence. Whilst one reported relying on the patient volunteering a compliance of less than 50% to be deemed as non-compliant, the actual assessment for the other studies was much less clear. They did not provide any detailed information regarding the nature of these discussions and how exactly the adherence was assessed. Given the direct involvement of the responsible clinician in assessing adherence, each of these studies was at high risk of bias.

Association between adherence and outcome

Just over half of the included studies (n = 9) considered the association between adherence data and study outcomes. The nature of these associations varied widely. Some studies provided a narrative description of associations only, whereas others provided quantitative statistical comparisons of outcomes or correlations between adherence and outcome. Much of this variety was related to the wide variation in final reporting of adherence data. There was also significant heterogeneity in the results of the reported association. Whilst some papers reported an improvement in clinical outcome with improved adherence, others did not find any difference. The reporting of associations between adherence and outcome is summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

information of association between adherence and outcome

| Study name | Type of association | What was reported? | Were outcomes improved in compliant patients? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuff 2012 [9] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Comparison of outcomes between compliance groups | Yes |

| Groth 1994 [10] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Comparison of outcomes between compliance groups | Yes |

| Guillodo 2011 [23] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Correlation between length of brace use + subjective assessment of recovery | No |

| Midgley 2011 [25] | Narrative analysis | States no difference in outcomes with length of orthosis use | No |

| O’Brien 2011 [11] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Correlation between compliance + clinical outcome | Mixed |

| Rives 1992 [13] | Descriptive quantitative analysis | Outcomes for each group without statistical comparison | Yes |

| Roh 2016 [12] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Multivariate regression analysis of adherence as a predictor of outcome | Yes |

| Sandford 2008 [28] | Narrative analysis | Recorded individual compliance of patients with poor outcome | Inconclusive |

| Silverio 2014 [27] | Statistical quantitative analysis | Correlation between compliance + clinical outcome | No |

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review to identify, summarise, and critically appraise methods for assessing adherence to removable orthoses used after surgery or trauma to the appendicular skeleton. In the 17 included studies, patient self-report questionnaires were the most commonly used method of measuring adherence. These were commonly multi-item questionnaires, but single-item questionnaires, home diaries, and informal history taking were also used. Overall, there was a lack of consistency in the target behaviour assessed, the timing and frequency of assessment across studies, and whether adherence overall was scored. None of the instruments was validated in the study population. Approximately half of the included studies used methods of assessing adherence that minimised response bias (e.g. postal questionnaires), but the remaining studies used methods such as direct questioning which may have impacted on participants’ responses or did not provide sufficient details (e.g. how and by whom the measure was administered) for the risk of bias in the assessment to be assessed. The lack of consistency in the way that adherence is measured and reported was unanticipated, given the importance of the adherence in orthosis use and its potential impact on outcomes. A validated approach for assessing adherence to removable orthoses is recommended to be used in studies evaluating their effectiveness and will be vital in any future splinting trial. To our knowledge, no such measures exist, and work to develop suitable tools is therefore required. Such measures may need to include reasons for non-compliance.

The challenges of measuring adherence are not unique to orthosis use. Systematic reviews have previously evaluated methods used to assess adherence to medication usage [32], home-based rehabilitation [17], and prescribed exercise [33]. The most widely studied field is that of adherence to medication, with a wide range of tools being designed and validated over the past four decades, and yet none of them can be considered the gold standard [32]. The ideal adherence measure should be economically viable, user friendly, reliable, sensitive, and practical [34, 35]. As no single measure has been found to meet all of these standards, a combination of methods is often recommended to account for the limitations of individual tools [35].

The vast majority of the measurement tools identified in this study were self-reported measures. These provide a low-cost, flexible, practical, and easily implemented measure of adherence. Given the unsupervised nature of recommended orthosis use, these measures provide a straightforward method of collecting otherwise difficult-to-obtain adherence data. However, they do have significant limitations. It has long been known that patients are often unwilling to admit non-adherence [4], and measures may overestimate the true value. Self-reported measures are vulnerable to social desirability bias, with respondents providing answers they feel will please their healthcare professionals [36]. This is a particular problem if the measure is administered by a clinician. Self-report questionnaires may reduce this, but recall bias should be considered if the adherence is assessed several weeks after the injury or intervention. These factors, combined with the study-specific non-validated nature of the measures used, call into question the reliability of the adherence data reported in these studies. These problems have also been shown in other settings. Indeed, Shi et al. [37] reviewed 41 studies assessing the agreement between self-reported measures of medication adherence and electronic drug monitoring and demonstrated a significantly lower correspondence between self-report and electronically monitored adherence when non-named, non-standardised self-reported measures were used.

The widespread use of non-standardised study-specific instruments also limits the comparability of study findings and the ability to pool data in meta-analyses, as highlighted in previous systematic reviews [38, 39]. Although improving adherence to recommended therapies is widely considered to improve outcomes [40, 41], the nature of this relationship is not always straightforward. The complexity of this association may partly be explained by the poor-quality measurement of adherence data that currently exists. There is therefore a need for a validated standardised measure of adherence for use in this setting to improve the quality and comparability of future research in this field.

There are several limitations to our systematic review. Firstly, the review was restricted to papers including the term adherence in the title or abstract. This approach may have excluded studies where relevant methods of assessing adherence were used but not reported in the abstract. The focus of this review, however, was specifically to evaluate methods of measuring adherence, and most of the studies providing a detailed description of this process measure commented on this in the abstract. Restricting the review to use of orthoses in acute settings is another potential weakness. However, the psychological underpinnings of adhering to short-term and long-term treatments with a removable orthosis in these circumstances are likely very different; thus, they potentially require different monitoring approaches for optimisation [42]. A similar rationale can be applied to restricting the review to adults. Overall, however, this study has provided a snapshot of current methods for assessing adherence to orthosis use, and has demonstrated the need for improvement.

Given the importance of adherence to orthosis use in determining outcomes in research and clinical practice, there is a need to improve the quality and consistency of the measurement and reporting of this key outcome. This is particularly relevant to ongoing trials such as Osteoarthritis Thumb Therapy (OTTER) II (ISRCTN 54744256) where the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a splint is being compared to a placebo splint and optimal self-management for the treatment of symptomatic thumb osteoarthritis [43]. A valid, robust, and reliable measure is therefore required that is acceptable to patients and can be used across all studies. This may be challenging, given the variation in types of orthoses used, recommendations regarding duration of use, and other clinical variables, and any measure would need to be sufficiently flexible to meet these needs. However, there are generic components of adherence to orthoses that could be included. We recommend that work with key stakeholders including surgeons, therapists, and patients and their carers is needed to ensure that the measure is appropriate and can be effectively used across different conditions. Key design features will include ease of use and digital solutions, as electronic patient-reported outcomes have been shown to be useful in similar patient groups [44].

However, more objective measures of adherence are also likely to be needed [45], and technological advances such as the development of sensors that can be placed in any orthosis may offer an ideal solution by allowing accurate and detailed information to be reliably collected with minimal burden to patients [46, 47]. Such sensors are amenable for use in a trial setting and are also cheap and relatively ‘low tech’, making it possible to integrate them into routine practice.

This review has highlighted the need to improve methods for assessing patient adherence to orthoses following surgery, but development of appropriate tools will take time, and simple recommendations to improve the quality and value of upcoming and ongoing work can be proposed based on the findings of this review. Firstly, it is vital that trialists select measures that capture the most important aspects of adherence for their study and aim to collect data in a way that represents a minimal burden to patients whilst minimising bias. Self-completed patient questionnaires may represent the best option, and it may be possible to validate instruments already in use.

Assessing adherence may also be more important at different stages in evaluation. Robust assessment would be particularly important in explanatory trials when determining if an orthosis was an appropriate treatment in an ideal settling with a compliant patient, but it may be less important in a large-scale pragmatic study when the aim would be to evaluate effectiveness in the ‘real world’. Similarly, reasons for non-compliance to orthosis use would have particular value in the pilot and feasibility stages of a trial. It may be that the instructions for use or the orthosis itself could be modified based on patient feedback so that the intervention would be more acceptable to patients in the main study and thus more likely to be used. At present, the best recommendations for trialists involved in studies using orthosis are that details of any methods used for assessing adherence be well described (e.g. included as a study additional file) and transparently reported so that readers can judge for themselves the methods used and the results. Transparent reporting of any statistical analysis used for assessing the impact of adherence on outcomes is similarly vital, including details of any assumptions made and any limitations of the measures used. Researchers should take care when interpreting their findings to take account of the limitations of the measures of adherence currently used and to acknowledge these issues when discussing the implications of the results for both further research and clinical practice.

Conclusions

Measurement and reporting of adherence to orthosis use is currently inconsistent, resulting in problems with interpretation of relevant literature and impacting on understanding of the efficacy of orthoses prescribed in the acute setting following injury or surgery. Further research is required to develop measurement tools that provide a rigorous and reproducible assessment of adherence in this acute population.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Search strategy MEDLINE (Ovid).

Authors’ contributions

JMB conceived the review; ZT, SP, IAK, JH, AJ MDK, and JMB designed the study; GD, ZT, DY, and JH extracted the data; GD performed the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; SP substantially revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

This work was funded by a pump-priming grant from the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons and the British Society for Surgery of the Hand and undertaken with the support of the Medical Research Council (MRC) ConDuCT-II (Collaboration and innovation for Difficult and Complex randomised controlled Trials In Invasive procedures) Hub for Trials Methodology Research (MR/K025643/1) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. Shelley Potter is an NIHR Clinician Scientist (CS-2016-16-019). Jane Blazeby is an NIHR Senior Investigator. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in the design or reporting of this work.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gareth Davies, Email: gareth.davies@doctors.org.uk.

Daniel Yeomans, Email: dan.yeomans@gmail.com.

Zoe Tolkien, Email: zoetolkien@gmail.com.

Irene A. Kreis, Email: ikreis@rcseng.ac.uk

Shelley Potter, Email: shelley.potter@bristol.ac.uk.

Matthew D. Gardiner, Email: mdgardiner@gmail.com

Abhilash Jain, Email: abhilash.jain@kennedy.ox.ac.uk.

James Henderson, Email: jameshendersonplasticsurgery@gmail.com.

Jane M. Blazeby, Email: J.M.Blazeby@bristol.ac.uk

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13063-020-04456-2.

References

- 1.Sabaté E, World Health Organization, editor. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singal AG, Higgins PDR, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5(1):e45. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2013.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podell RN, Gary LR. Compliance: a problem in medical management. Am Fam Physician. 1976;13(4):74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meichenbaum D, Turk DC. Facilitating treatment adherence: a practitioner’s guidebook. New York: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vos RJ, Weir A, Visser RJA, de Winter T, Tol JL. The additional value of a night splint to eccentric exercises in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(7):e5. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.032532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altan E, Alp NB, Baser R, Yalçın L. Soft-tissue mallet injuries: a comparison of early and delayed treatment. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(10):1982–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooksbank K, Jenkins PJ, Anthony IC, Gilmour A, Nugent MP, Rymaszewski LA. Functional outcome and satisfaction with a “self-care” protocol for the management of mallet finger injuries: a case-series. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2014;8(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13032-014-0021-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke MW, Marsh JL, Clark M, Nakash R, Jarvis RM, Hutton JL, et al. Treatment of severe ankle sprain: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of mechanical ankle support with tubular bandage. The CAST trial. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2009;13(13):iii. doi: 10.3310/hta13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Prospective evaluation of postoperative compliance and outcomes after rotator cuff repair in patients with and without workers’ compensation claims. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2012;21(12):1728–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groth GN, Wilder DM, Young VL. The impact of compliance on the rehabilitation of patients with mallet finger injuries. J Hand Ther. 1994;7(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(12)80037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien LJ, Bailey MJ. Single blind, prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing dorsal aluminum and custom thermoplastic splints to stack splint for acute mallet finger. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(2):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roh YH, Lee BK, Park MH, Noh JH, Gong HS, Baek GH. Effects of health literacy on treatment outcome and satisfaction in patients with mallet finger injury. J Hand Ther. 2016;29(4):459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rives K, Gelberman R, Smith B, Carney K. Severe contractures of the proximal interphalangeal joint in Dupuytren’s disease: results of a prospective trial of operative correction and dynamic extension splinting. J Hand Surg. 1992;17(6):1153–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD000011. 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bollen JC, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, Howe TE, Goodwin VA. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost R, Levati S, McClurg D, Brady M, Williams B. What adherence measures should be used in trials of home-based rehabilitation interventions? A systematic review of the validity, reliability, and acceptability of measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(6):1241–56.e45. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.08.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Hernon M, Hughes K, Kelly G, Lonsdale C, et al. Measurement tools for adherence to non-pharmacologic self-management treatment for chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(3):552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AlGhurair SA, Hughes CA, Simpson SH, Guirguis LM. A systematic review of patient self-reported barriers of adherence to antihypertensive medications using the World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. 2012;14(12):877–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Itoigawa Y, Omi R, Shinozaki N, Yamamoto N, et al. Is protecting the healing ligament beneficial after immobilization in external rotation for an initial shoulder dislocation? Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1126–1132. doi: 10.1177/0363546513480620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, Enger M, Soldal LA, Svenningsen S. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg-Am Vol. 2011;93(10):897–904. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swirtun LR, Jansson A, Renström P. The effects of a functional knee brace during early treatment of patients with a nonoperated acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: a prospective randomized study. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(5):299–304. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000180018.14394.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelan DB, Litchfield R, Wambolt E, Dainty KN. Joint Orthopaedic Initiative for National Trials of the Shoulder (JOINTS). External rotation immobilization for primary shoulder dislocation: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop. 2014;472(8):2380–2386. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3432-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillodo Y, Le Goff A, Saraux A. Adherence and effectiveness of rehabilitation in acute ankle sprain. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;54(4):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath MS, Ulrich SD, Bonutti PM, Smith JM, Seyler TM, Mont MA. Evaluation of static progressive stretch for the treatment of wrist stiffness. J Hand Surg. 2008;33(9):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midgley R, Toemen A. Evaluation of an evidence-based patient pathway for non-surgical and surgically managed metacarpal fractures. Hand Ther. 2011;16(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rankin AE, Kramer JF, Fowler PJ, Kirkley A. Survey of knee brace usage following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physiother Can. 2000;52(3):215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverio LM, Cheung EV. Patient adherence with postoperative restrictions after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2014;23(4):508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandford F, Barlow N, Lewis J. A study to examine patient adherence to wearing 24-hour forearm thermoplastic splints after tendon repairs. J Hand Ther. 2008;21(1):44–53. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wollstein R, Rodgers J, Ogden T, Loeffler J, Pearlman J. A novel splint for proximal interphalangeal joint contractures: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(10):1856–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang P-W, Wu H-T, Chiang C-C, Lin H-D. Lisfranc fracture dislocation due to Charcot joint in a type 2 diabetic woman. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2011;22(3):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zelikovsky N, Schast AP. Eliciting accurate reports of adherence in a clinical interview: development of the Medical Adherence Measure. Pediatr Nurs. 2008;34(2):141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication adherence measures: an overview. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:217047. doi: 10.1155/2015/217047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawley-Hague H, Horne M, Skelton DA, Todd C. Review of how we should define (and measure) adherence in studies examining older adults’ participation in exercise classes. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011560. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(5):331–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther. 1999;21(6):1074–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi L, Liu J, Koleva Y, Fonseca V, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M. Concordance of adherence measurement using self-reported adherence questionnaires and medication monitoring devices. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(12):1097–1107. doi: 10.2165/11537400-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson D, Jerosch-Herold C. Clinical effectiveness of post-operative splinting after surgical release of Dupuytren’s contracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EE, Foster NE. Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(1):CD005956. 10.1002/14651858.CD005956.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Johnson MJ, Williams M, Marshall ES. Adherent and nonadherent medication-taking in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin Nurs Res. 1999;8(4):318–335. doi: 10.1177/10547739922158331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–314. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Brien L. Adherence to therapeutic splint wear in adults with acute upper limb injuries: a systematic review. Hand Ther. 2010;15(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams J, Barratt P, Arden NK, et al. The Osteoarthritis Thumb Therapy (OTTER) II Trial: a study protocol for a three-arm multi-centre randomised placebo controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and efficacy and cost-effectiveness of splints for symptomatic thumb base osteoarthritis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028342. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028342.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen J, Marx R, Hidaka C, Wilson S, Lyman S. Validation of electronic administration of knee surveys among ACL-injured patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(10):3116–3122. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitolins MZ, Rand CS, Rapp SR, Ribisl PM, Sevick MA. Measuring adherence to behavioral and medical interventions. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(5 Suppl):188S–194S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zarowin J, Warnick E, Mangan J, Nicholson K, Goyal DKC, Galetta MS, et al. Is wearable technology part of the future of orthopedic health care? Clin Spine Surg. 2020;33(3):99–101. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aldebeyan S, Aoude A, Harvey EJ. Electronics and orthopaedic surgery. Injury. 2018;49(Suppl 1):S102–S104. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(18)30313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Search strategy MEDLINE (Ovid).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.