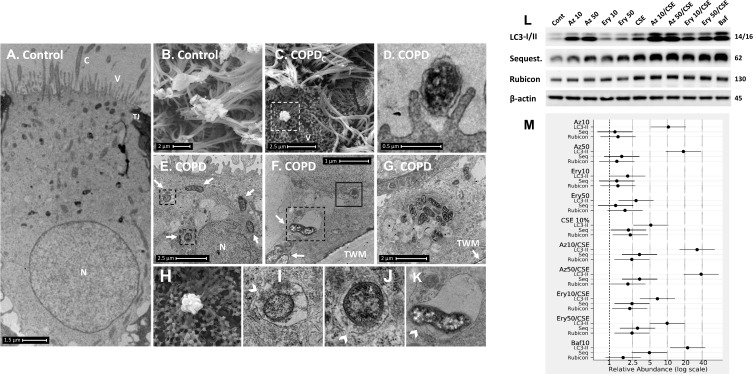

Figure 2.

COPD-derived airway epithelial cells and COPD-related exposures exhibit intracellular NTHi and arrested autophagic flux, respectively. Control and COPD human air–liquid interface cultures exhibiting mucociliary differentiation and three-dimensional growth characteristics were assessed. (A–K) Transmission and scanning electron micrographs (TEM/SEM, respectively) of differentiated cultures infected with NTHi. (A and B) Control cells possess abundant cilia (C), villi (V) and apicolateral interaction via tight junctions (TJ). Intracellular NTHi was not observed within AEC after 24 h co-culture (electron dense puncta are cytosolic granules, lysosomes and mitochondria), perhaps due to exclusion from the villi by mucociliary activity/interactions. C and D. COPD-derived cultures associate with NTHi via exposed villi that appear to approximate towards the bacteria (C, dashed box, that is enlarged in H (SEM)), and that are resolved with TEM (D) as membrane projections and pits that interact with NTHi. (E) COPD-derived cultures exhibit NTHi in the cytoplasm (white arrows), that interact with vesicular structures (dashed box). Magnified images for D (I and J) show the NTHi cell wall remains defined while within vesicles. (F) NTHi (white arrows) within proximity to the transwell membrane (TWM) indicates a mode to passage from apical cells to the basal progenitor cell layer. Further, NTHi in vesicles (eg dashed box) which is magnified in (K) remains unaffected by degradative processes in proximity to autophagic activity (solid box). (G) A cluster of NTHi in the basal progenitor cell layer suggests replicative activity, and may indicate an initial stage leading to the formation of an intracellular bacterial community. Discontinuity in the vesicular envelopes for E-F (white chevrons in magnified images (I), (J) and (K) may be caused by NTHi attempting to escape into the cytosol). Data is representative of n=3 COPD and n=3 control AEC donor cultures. (L) Western blot analysis for canonical (LC3-I/II and Sequestosome (Sequest.)) and non-canonical (Rubicon) autophagy factors demonstrate a block in autophagic flux after exposure to 10% cigarette smoke extract (CSE), and the macrolides azithromycin (Az, μg/mL) and erythromycin (Ery, μg/mL). Co-exposure with CSE and either macrolide produces a striking block in flux as evidenced by an increase in LC3-II concomitant with elevation of the autophagy receptor Sequestosome which is normally co-degraded with the cargo during unrestricted autophagy. Exposure to bafilomycin (10 nM) was included as a positive control for the blockade of autophagic flux. Rubicon, an essential component for LC3-Associated Phagocytosis and a negative regulator of canonical autophagy, is moderately upregulated by CSE. (M) Quantitative analysis of protein expression confirms a strong increase in LC3-II and Sequestosome with the combination treatments, that approximates the effect observed for bafilomycin for the Az/CSE exposure. Protein expression is expressed as relative abundance and normalised to the untreated sample and β-actin. Intervals are 95% CI, and results are significant if the confidence intervals do not cross 1, and significant between exposures when CI do not overlap. Exposure period was 24 h for n=4 primary cultures from control individuals.