Abstract

The relationship between parent and child changes around adolescence, with children believed to have: (i) an earlier puberty if they have less secure attachments to their carer; (ii) a phase of increased conflict behaviour toward their carer; and (iii) heightened conflict behaviour when carer attachments are less secure. We find support for analogous associations in adolescent dogs based on behaviour and reproductive timing of potential guide dogs. Bitches with behaviour indicative of insecure attachments pre-adolescence became reproductively capable earlier. Providing the first empirical evidence to our knowledge in support of adolescent-phase behaviour in dogs, we found a passing phase of carer-specific conflict-like behaviour during adolescence (reduced trainability and responsiveness to commands), an effect that was more pronounced in dogs with behaviour indicative of less secure attachments. These results indicate a possibility for cross-species influence on reproductive development and highlight adolescence as a vulnerable time for dog–owner relationships.

Keywords: adolescence, dog, attachment, sensitive period, human–animal interaction, puberty

1. Introduction

Parent–child relationships share a surprising number of similarities with owner–dog relationships, including analogous behavioural and hormonal bonding mechanisms [1,2]. Adolescence is a vulnerable time for parent–child relationships, but little is known about owner–dog relations during adolescence. Adolescence is the final developmental stage of reproductive function, in which a juvenile becomes an adult, and incorporates puberty. In mammals, dramatic hormonal changes and reorganization of the brain [3,4] occur during puberty. When puberty starts so will potentially competing motivations in the domestic dog: to breed with conspecifics and to live in the care of humans. Together this means adolescence could be a vulnerable time for owner–dog relationships.

During puberty in humans, and alongside changes to hormones [5] and brain reorganization [6], there are transitory changes in risk taking, mood, irritability and conflict with parents (collectively known as ‘adolescent-phase behaviour’). Increased adolescent conflict behaviour between child and parent (generally mundane disagreements) is believed to be related to a need for individuation or autonomy [7,8]. Children with insecure attachments towards their carers are observed to have greater conflict and risk taking [9,10]. The timing of puberty is also associated with the quality of early relationships: children have an earlier onset of puberty if they have less attached, more insecure, relationships with carers [9,11–14].

Owing to behavioural and physiological similarities between parent–child and owner–dog relationships, the aim of this study was to examine the extent to which adolescence in dogs shares characteristics of adolescence in humans. Specifically, we investigated owner–dog parallels of three proposed characteristics of human parent–adolescent relations: (i) an earlier puberty for female dogs with less secure attachments to their carer; (ii) adolescent-phase conflict behaviour exhibited toward their carer; and (iii) greater conflict behaviour in dogs with less secure attachments to their carer.

2. Results

(a). Influence of attachment on puberty

To investigate an association between attachment and puberty, we collected prospective data on attachment behaviour and monitored puberty (indicated by the first proestrus) in a cohort of 70 potential guide dog bitches born in 2012 (German shepherd dogs, golden and Labrador retrievers, and crosses of these). Attachment can be characterized by proximity seeking and distress upon separation [15] and relevant questions are found in two scales of the validated and widely used C-BARQ questionnaire [16], which we scored on a visual analogue scale (VAS). The first, Attachment and Attention Seeking was scored as a mean of six behaviours related to proximity seeking (e.g. ‘Tends to sit close to or in contact with you…’, ‘Displays a strong attachment for one… member of the household’) and the second, Separation-Related Behaviour, was scored as a mean of nine behaviours (e.g. ‘Shakes shivers of trembles when left, or about to be left’, ‘Appears agitated…when separated from you…’). We were able to confirm that these two scales were measuring insecure attachments, as higher scores in both scales were found in dogs categorized as insecurely attached based upon direct behaviour observations and using methods based on [17] (see Methods details in the electronic supplementary material). Since insecure attachments and pubertal timing could both be related to general fearfulness we also considered associations between puberty timing and a scale of general anxiety designed for this population [18]. Questions for these scales were completed by the dog's main carer, a Guide Dogs UK puppy walker whom the dog lives with from approximately 2 to 3 until 12 to 14 months of age.

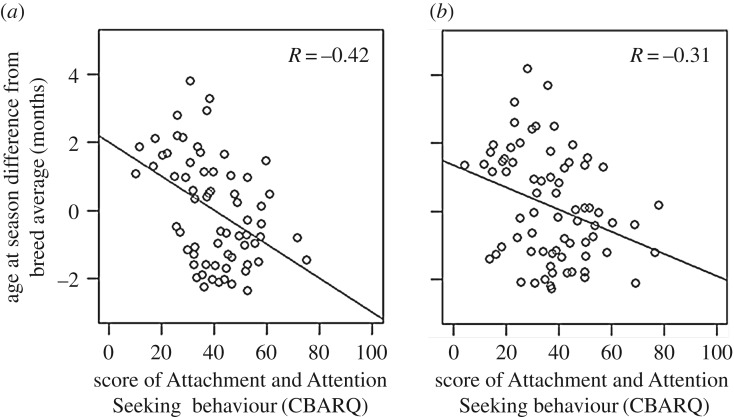

Attachment and Attention Seeking was positively correlated with the age at which bitches had their first proestrus compared with their breed mean (calculated from population-level Guide Dogs UK records of all dogs born from 2012 to 2014). Bitches that displayed more Attachment and Attention Seeking behaviour at 5 months of age entered puberty earlier (figure 1a, R = −0.423, n = 64, p = 0.0004, based on partial correlation, controlling for diet and shared parentage confounds; and figure 1b, with no control for confounds, R = −0.315, n = 70, p = 0.007). Higher scores of Separation-Related Behaviour at 5 months of age were associated with entering puberty earlier when controlling for confounds (R = −0.295, n = 70, p = 0.014), but were not associated without control for confounds (R = −0.115, n = 70, p = 0.343). General anxiety was not associated with the timing of puberty without (R = −0.048, n = 70, p = 0.691) or with control for confounds (R = −0.134, n = 67, p = 0.271).

Figure 1.

The negative association between insecure attachment behaviour measured by carers at 5 months and puberty end (first proestrus) relative to breed norm, based on: (a) partial correlation controlling for confounds of shared parentage and diet type; (b) correlation with no control for confounds. Attachment and Attention Seeking was scored on a 100 mm visual analogue scale, with a higher score indicating an insecure attachment.

(b). Adolescent-phase conflict behaviour

To investigate adolescent-phase conflict behaviour, we observed and scored obedience response of 93 dogs (41M: 52 F, breeds and cross breeds of: golden and Labrador retrievers) to an established command given by a carer and a consistent stranger in a controlled setting [19] (see Methods details in the electronic supplementary material). We predicted that dogs would be less obedient during adolescence, demonstrating an adolescent-phase of conflict with their primary carer. Reduced responsiveness to a well-established command (‘sit’) was considered as a proxy for reduced obedience. The population of dogs were sampled at pre-adolescent (n = 82 aged 5 months) and adolescent (n = 80 aged 8 months, of which 69 were tested at both time points) time periods. Dogs responded less to the ‘sit’ command during adolescence, but only when the command was given by their carer, not a stranger (the carer and stranger were the same people at both time points). The odds of repeatedly not responding to the ‘sit’ command were higher at 8 months compared with 5 months for the carer (odds ratio (OR) = 2.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.46–3.11, Z = 2.01, p = 0.044). However, the response to the ‘sit’ command improved for the stranger between the 5- and 8-month tests (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.25–0.63, Z = 1.96, p = 0.049).

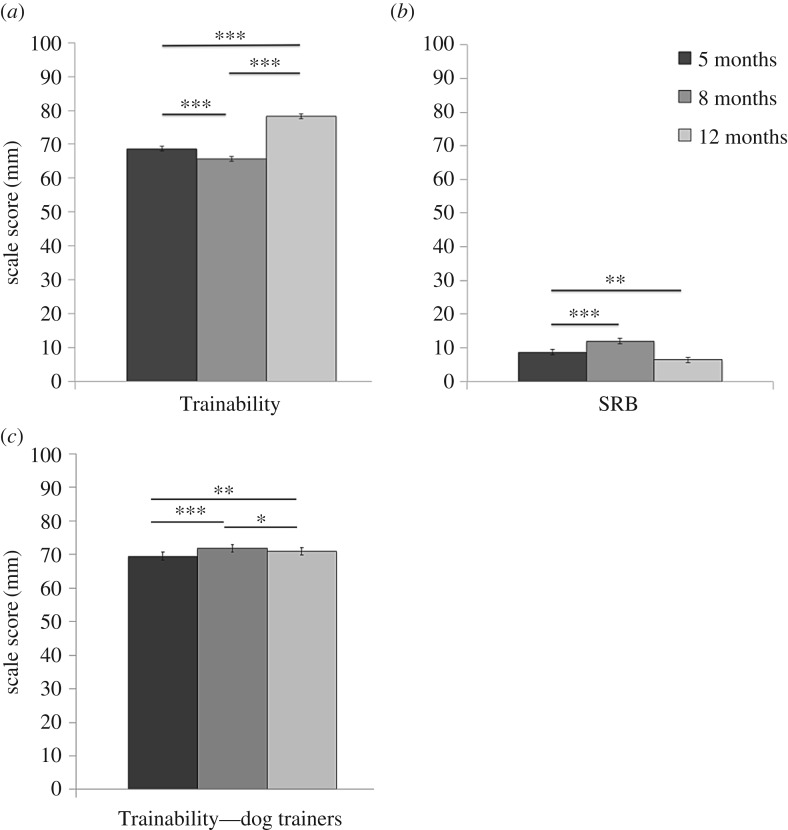

Further evidence of a transitory adolescent-phase of disobedience confirming these findings was also found in data collected from a larger cohort of dogs (n = 285, 135 M : 150 F, breeds and cross breeds of: golden retriever, Labrador retriever and German shepherd dog) using the scale of ‘Trainability’ from two validated guide dog behaviour questionnaires completed by the dog's main carer [20], and a trainer (puppy training supervisor) less familiar to the dog [18]. Trainability was a mean of VAS scores to five questions (e.g. ‘This dog…refuses to obey commands, which in the past it was proven it has learned’, ‘Responds immediately to the recall command when off lead’). Carers assigned lower scores of Trainability to dogs around adolescence (8 months), than pre-adolescence (5 months of age) and post-adolescence (12 months). For carers, there was a 5- to 8-month decrease (cross-classified random effects GLM: Z = −4.46, p < 0.001) and a 5- to 12-month increase in Trainability on the questionnaire scale (Z = 13.76, p < 0.001, figure 2a). By contrast, the dog's trainers reported an increase in Trainability when adolescent (5- to 8-month increase: Z = 5.42, p < 0.001, figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Scores for (a) Trainability (higher is more ‘trainable’) and (b) Separation-Related Behaviour (SRB, from C-BARQ where higher scores indicate more Separation-Related Behaviour displayed), as scored by dog carers (puppy walkers) when dogs were aged 5, 8 and 12 months. Scores for (c) Trainability when scored by the dogs' training supervisors when dogs were aged 5, 8 and 12 months. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent s.e. of ±1.

(c). Adolescent-phase conflict behaviour and attachment

Questionnaires completed by dog carers were used to investigate whether adolescent conflict behaviour was associated with dog–carer attachment. Mirroring the transitory adolescent-phase of conflict was a phase of higher scores for Separation-Related Behaviour towards the carer. Scores for Separation-Related Behaviour were 36% higher at adolescence (8 months) than pre-adolescence (5 months) and post-adolescence (12 months) (5- to 8-month increase GLM: Z = 4.11, p < 0.001, and 5 to 12-month decrease GLM: 0.77, Z = 3.02, p < 0.01, figure 2b). Increased Separation-Related Behaviour at 8 months was associated with lower obedience (Trainability score) to their carer at 8 months of age (random effects GLM: R = −0.516, t = −10.37, p < 0.001), but not at 5 or 12 months. Scores of Attachment and Attention Seeking did not change with age, but they were correlated with Trainability at 8 months of age only (R = −0.298, t = −4.31, p < 0.001).

3. Discussion

The strength of attachment between humans and dogs is made possible by dogs piggybacking on human mechanisms for bonding with children [1,2]. Here, we find evidence to suggest that the human–dog attachment may in turn influence dog behaviour and reproductive physiology during puberty. Specifically, our results find an association between earlier puberty and an insecure attachment to a human carer. This replicates correlational findings from human adolescents who enter puberty earlier if they do not have strong attachments to parental figures [12]. Additionally, we found when dogs reached puberty, they were less likely to follow commands given by their carer, but not by others. The socially-specific nature of this behaviour in dogs (reduced obedience for their carer only) suggests this behaviour reflects more than just generalized hormonal, brain and reward pathway changes that happen during adolescence. In parts of this study, the ‘other’ person was a guide dog trainer who may have been more capable of getting a dog to perform a command; however, the results are consistent with parts of the study when the ‘other’ person was an experimenter without the experience of dog training. We also find the reduction in obedience to the carer and not an ‘other’ person to be specific to the dog's developmental stage and more pronounced in dogs with insecure attachments, which is not easily explained by differences in dog training ability between the carer and other.

We find support for the prediction that conflict behaviour is associated with less secure carer attachments during an adolescent-phase, because behaviour indicative of insecure or anxious attachments was only associated with obedience at an age that corresponds with adolescence. A weakness of this study is that puberty was not measured in all dogs, rather it was assumed based on existing knowledge of pubertal timing in relevant breeds (noting that age groupings would need to be reconsidered for different breeds). Further, when puberty was measured, our definition of the onset of puberty in females (first proestrus) was reductionist as some bitches may not have entered a complete cycle. We cannot preclude the possibility that the small minority of dogs were incorrectly classified as pubertal; however, this would be more likely to lead to a type II rather than type I error.

Research in rats and humans shows that adolescence is a sensitive period for development in mammals owing to the extensive reorganization of the brain's neural circuitry (see [21] for an overview). The possibility that puberty is a sensitive period in dogs warrants further investigation, particularly as experiences at this time could have long-term impacts on behaviour. A sensitive period around puberty is proposed in grey literature (e.g. within dog training literature); however, to our knowledge this is the first study to provide empirical support for this.

Reproductive development is known to be influenced by social relationships in a wide range of species [22], but this study highlights the possibility for cross-species influences on reproductive development. Like human adolescents, we find dogs' attachment behaviour to their carers is associated with the age at which puberty starts. It is likely that the carers' behaviour influences the dog's attachment to them [23]; indeed correlations have been found between human and dog attachments [24–26]. Understanding the specific behavioural influences on more secure attachments is an area for future study.

Our findings support dogs as a potential model species for studying puberty in humans. This is a particularly important area of study because early puberty is associated with more risky behaviour, earlier death, repeat offending, narcotics abuse and mental health problems [27]. Experimental studies of human puberty or attachment are not ethically possible but may be considered in dogs. Such studies could elucidate the causal link between attachment and pubertal timing, along with other aspects of adolescence. It will be important to confirm our results in future studies, because it is possible the similar results could arise from different explanatory mechanisms in dogs compared with humans.

We found that dogs displaying behaviour indicating they are stressed by separation from their main carer were also increasingly disobedient towards that same person. This finding emulates human research, where increases in conflict with parents during adolescence have been associated with insecure attachments [28]. An alternative explanation for our results is that some dogs received poorer training both in obedience and in being separated from their carer; however, our sample of trainee guide dogs were provided with standardized training to gradually introduce them to being left alone.

In humans, the conflict between parents and adolescents is proposed to function to test and potentially re-establish secure attachments [29]. A lack of secure attachments during childhood [30] and adolescence [31] is associated with earlier reproduction. In dogs, it is possible that the attachment to a carer acts as a cue of environmental quality, where the carer is the main source of survival. In this case, the attachment could have an evolutionary function to mediate between life-history strategies that favour roaming and early reproduction, versus continued human care and delayed reproduction.

In most dogs, it seems that adolescent-phase disobedient behaviour exists, but does not last. Unfortunately, the welfare consequences of adolescence-phase behaviour could be lasting because this corresponds with the peak age at which dogs are relinquished to shelters [32,33]. Welfare could be also be compromised if problem behaviour results in the use of punishment-based training methods [34] or causes carers to disengage, as it does in humans [35]. It is hoped these issues could be avoided if dog owners were made aware that (as in humans) problem behaviour during adolescence could be just a passing phase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without Peter Craigon, Kathleen Gallagher, Caroline McMillian, David Griffiths, Sue Richardson, Logan Anderson, Sarah Miller, Barry Cahill, David Hurst, Rachel Moxon, Simon Blythe, and the trainers, carers and dogs who participated. Thanks to Alan McElligott, Rachel Moxon and four reviewers for insightful comments on the manuscript.

Ethics

We received ethical approval from the School of Veterinary Medicine and Sciences Ethics Committee, who acted as the Institutional Review board, project no. 170510. Approval was also gained by Guide Dogs UK internal review. Informed consent was received from all participants of the ‘sit’ response test and from Guide Dogs UK for the participation of the dogs.

Data accessibility

Currently provided as electronic supplementary material, but will be publicly available in the Newcastle University repository upon acceptance to allow tracking of downloads etc. Data are freely available in Dryad and can be accessed at doi:10.25405/data.ncl.12066270 [36].

Authors' contributions

L.A. and G.C.W.E. conceived the study, and designed the study together with N.D.H., who was responsible for the acquisition of the data. R.S. was responsible for designing and collecting a subset of data in the behaviour observations. N.D.H. and L.A. analysed the data and together with G.C.W.E. and R.S. were responsible for the interpretation of the data. L.A. and N.D.H. drafted the manuscript with revisions from G.C.W.E. and R.S. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by Guide Dogs, UK (grant number CR2009-01a; http://www.guidedogs.org.uk) and the University of Nottingham as part of a 6-year longitudinal study, with some additional input through BBSRC grant BB/J014508/1.

References

- 1.Romero T, Nagasawa M, Mogi K, Hasegawa T, Kikusui T. 2014. Oxytocin promotes social bonding in dogs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9085–9090. ( 10.1073/pnas.1322868111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagasawa M, Mitsui S, En S, Ohtani N, Ohta M, Sakuma Y, Onaka T, Mogi K, Kikusui T. 2015. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science 348, 333–336. ( 10.1126/science.1261022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisk CL, Zehr JL. 2005. Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 26, 163–174. ( 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisk CL, Foster DL. 2004. The neural basis of puberty and adolescence. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1040–1047. ( 10.1038/nn1326) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Becker JB. 1992. Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones: evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior at adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 111, 62–107. ( 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM. 2002. Amygdalo-cortical sprouting continues into early adulthood: implications for the development of normal and abnormal function during adolescence. J. Comp. Neurol. 453, 116–130. ( 10.1002/cne.10376) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg L. 2001. We know some things: parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J. Res. Adolesc. 11, 1–19. ( 10.1111/1532-7795.00001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. 2006. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 255–284. ( 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberg L. 1988. Reciprocal relation between parent–child distance and pubertal maturation. Dev. Psychol. 24, 122–128. ( 10.1037/0012-1649.24.1.122) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg L, Belsky J. 1996. An evolutionary perspective on psychopathology in adolescence. In Adolescence: opportunities and challenges (eds D Cicchetti, SL Toth), vol. 7, pp. 93–124. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- 11.Belsky J, Steinberg L, Houts RM, Halpern-Felsher BL. 2010. The development of reproductive strategy in females: early maternal harshness, earlier menarche, increased sexual risk taking. Dev. Psychol. 46, 120–128. ( 10.1037/a0015549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belsky J, Houts RM, Fearon RMP. 2010. Infant attachment security and the timing of puberty: testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1195–1201. ( 10.1177/0956797610379867) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim K, Smith PK. 1998. Childhood stress, behavioural symptoms and mother–daughter pubertal development. J. Adolesc. 21, 231–240. ( 10.1006/jado.1998.0149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. 1991. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: and evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev. 62, 647–670. ( 10.1111/1467-8624.ep9109162242) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowlby J. 1958. The nature of the child's ties to his mother. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1958, 350–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu Y, Serpell JA. 2003. Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 223, 1293–1300. ( 10.2460/javma.2003.223.1293) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomon J, Beetz A, Schöberl I, Gee N, Kotrschal K. 2019. Attachment security in companion dogs: adaptation of Ainsworth's strange situation and classification procedures to dogs and their human caregivers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 21, 389–417. ( 10.1080/14616734.2018.1517812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey ND, Craigon PJ, Blythe SA, England GCW, Asher L. 2017. An evidence-based decision assistance model for predicting training outcome in juvenile guide dogs. PLoS ONE 12, e0174261 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0174261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey ND, Craigon PJ, Sommerville R, McMillan C, Green M, England GCW, Asher L. 2016. Test-retest reliability and predictive validity of a juvenile guide dog behavior test. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 11, 65–76. ( 10.1016/j.jveb.2015.09.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey ND, Craigon PJ, Blythe SA, England GCW, Asher L. 2016. Social rearing environment influences dog behavioral development. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 16, 13–21. ( 10.1016/j.jveb.2016.03.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey ND. 2019. Adolescence. In Encyclopedia of animal cognition and behavior (eds Vonk J, Shackelford TK). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasser SK, Barash DP. 1983. Reproductive suppression among female mammals: implications for biomedicine and sexual selection theory. Q Rev. Biol. 58, 513–538. ( 10.1086/413545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne E, Bennett PC, McGreevy PD. 2015. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 8, 71–79. ( 10.2147/PRBM.S74972) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fratkin JL. 2015. Examining the relationship between puppy raisers and guide dogs in training. PhD thesis, University of Texas at Austin. See https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/33291. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siniscalchi M, Stipo C, Quaranta A. 2013. ‘Like owner, like dog’: correlation between the owner's attachment profile and the owner-dog bond. PLoS ONE 8, e78455 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0078455) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman CL, Chen P, Serpell JA, Jacobson KC. 2013. Do dog behavioral characteristics predict the quality of the relationship between dogs and their owners? Hum. Anim. Interact. Bull. 1, 20–37. ( 10.1037/e565452013-003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golub MS, Collman GW, Foster PMD, Kimmel CA, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Reiter EO, Sharpe RM, Skakkebaek NE, Toppari J. 2008. Public health implications of altered puberty timing. Pediatrics 121, S218–S230. ( 10.1542/peds.2007-1813G) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen JP, Land D. 1999. Attachment in adolescence. In Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications (eds Cassidy J, Shaver PR), pp. 319–335. New York, NY: Guilford Press; See http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1999-02469-015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caffery T, Erdman P. 2000. Conceptualizing parent-adolescent conflict: applications from systems and attachment theories. Fam. J. 8, 14–21. ( 10.1177/1066480700081004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Del Giudice M. 2009. Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. Behav. Brain Sci. 32, 1–21, 21–67 ( 10.1017/S0140525X09000016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper ML, Shaver PR, Collins NL. 1998. Attachment styles, emotion regulation, and adjustment in adolescence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1380–1397. ( 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1380) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss E, Slater M, Garrison L, Drain N, Dolan E, Scarlett JM, Zawistowski SL. 2014. Large dog relinquishment to two municipal facilities in New York City and Washington, D.C.: identifying targets for intervention. Animals 4, 409–433. ( 10.3390/ani4030409) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.New JC, Salman MD, King M, Scarlett JM, Kass PH, Hutchison JM. 2000. Characteristics of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners compared with animals and their owners in U.S. pet-owning households. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 3, 179–201. ( 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0303_1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziv G. 2017. The effects of using aversive training methods in dogs—a review. J Vet. Behav. 19, 50–60. ( 10.1016/j.jveb.2017.02.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. 2004. Premature adolescent autonomy: parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. J. Adolesc. 27, 515–530. ( 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asher L, England GCW, Sommerville R, Harvey ND. 2020. Data from: Teenage dogs? Evidence for adolescent-phase conflict behaviour and an association between attachment to humans and pubertal timing in the domestic dog Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.25405/data.ncl.12066270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Asher L, England GCW, Sommerville R, Harvey ND. 2020. Data from: Teenage dogs? Evidence for adolescent-phase conflict behaviour and an association between attachment to humans and pubertal timing in the domestic dog Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.25405/data.ncl.12066270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Currently provided as electronic supplementary material, but will be publicly available in the Newcastle University repository upon acceptance to allow tracking of downloads etc. Data are freely available in Dryad and can be accessed at doi:10.25405/data.ncl.12066270 [36].