The world is facing a frightening pandemic due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) with thousands of severe infections and fatalities. Since no therapy has proven effective, an extraordinary race is taking place to identify an effective and safe treatment able to limit the disease progression and severity.

Two nonrandomized open‐label trials conducted in France and China 1 , 2 established the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine alone or combined with azithromycin in decreasing nasopharyngeal viral load and carriage duration in patients with COVID‐19, although evidence to support clinical benefits remained low. Thereafter, many studies, still unpublished in peer‐reviewed journals for the majority, showed contrasting results and revealed potential safety hazards (Table 1). 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 To date, multiple trials aiming at investigating chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine at various dose regimens to treat COVID‐19 (N = 81) or prevent the disease in high‐risk populations (N = 19) are cited on clinicaltrials.gov (accessed April 21, 2020). Interestingly, only 14 trials (17%) will investigate the azithromycin‐hydroxychloroquine combination.

Table 1.

Emerging List of Studies Investigating Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine With or Without Azithromycin to Treat COVID‐19

| Authors | Country | Design | N | Time in the Disease Course and Infection Severity | Groups and Dose Regimen | Main Resultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gautret et al 1 published |

France | Uncontrolled noncomparative observational study | 80 |

Early (d 5) Mild |

1 group, HCQ (200 mg ×3/d, 10 d) + AZ (500 mg on d 1 followed by 250 mg/d, 4 d) | Clinical improvement, rapid discharge, rapid fall in nasopharyngeal viral load, negative viral culture on d 5 in almost all patients |

| Chen et al 2 | China | Randomized open‐label parallel‐group trial | 62 |

Unknown Moderate |

2 groups, HCQ (200 mg ×2/d, 5 d) vs no HCQ | Significant clinical improvement based on body temperature recovery and cough remission times and increased recovery from pneumonia |

|

Chen et al 3 published |

China | Randomized open‐label controlled trial | 30 |

Early (d 6) Mild |

2 groups, HCQ (200 mg ×2/d, 5 d) vs no HCQ | No reduction in the percentage of negative SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid of throat swabs, the time from hospitalization to virus nucleic acid negative conservation, temperature normalization, and radiological progression |

|

Molina et al 4 published |

France | Uncontrolled noncomparative observational study | 11 |

Unknown Moderate |

1 group, HCQ (600 mg/d, 10 d) + AZ (500 mg/d, d 1 and 250 mg/d, d 2‐5) | Positive SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in 8/10 patients (80%, 95% confidence interval, 49%‐94%) at d 5‐6 after treatment initiation |

| Magagnoli et al 5 | United States | Retrospective cohort study | 368 |

Unknown Moderate |

3 groups, HCQ vs HCQ+AZ vs no HCQ (dosages not available) |

No reduction in mechanical ventilation Increased overall mortality in HCQ group |

| Mahévas et al 6 | France | Retrospective cohort study | 181 |

Early (d 7) Moderate |

2 groups, HCQ (600 mg/d within 48 h after admission) vs no HCQ | No reduction in ICU transfer or death, death within 7 d and ARDS within 7 d |

| Million et al 7 | France | Uncontrolled noncomparative observational study | 1061 |

Early (d 6) Mild |

1 group, HCQ (200 mg ×3/d, 10 d) + AZ (500 mg on d 1 followed by 250 mg/d, 4 d); analysis of the patients who took HCQ + AZ during at least 3 d | Significant reduction in mortality in comparison to patients treated with other regimens in all Marseille public hospitals |

| Barbosa et al 8 | United States | Retrospective cohort study | 63 |

Unknown Moderate |

2 groups, HCQ vs No HCQ (dosages not available) | Increased need for escalation of respiratory support and no benefits on mortality, lymphopenia, or neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio improvement |

| Tang et al 9 | China | Randomized open‐label controlled trial | 150 |

Delayed (day 16) Mild to moderate |

2 groups, HCQ (1200 mg/d for 3 d followed by 800 mg/d; total duration: 2 wks [mild/moderate] or 3 wks [severe]) vs no HCQ |

No differences in the overall 28‐d negative conversion rate, the negative conversion rate at d 4, 7, 10, 14, or 21, the improvement rate of clinical symptoms within 28 d, the normalization of C‐reactive protein and the blood lymphocyte count within 28 d Increased adverse events |

|

Borba et al 10 published |

Brazil |

Randomized double‐blinded parallel phase IIb trial Safety‐oriented study |

81 |

Early (d 7) Moderate |

2 groups, high‐dose CQ (600 mg ×2/d, f10 d, or total dose 12 g) vs low‐dose CQ (450 mg for 5 d, ×2/d only on the first day, or total dose 2.7 g) |

No differences in clinical outcome However, high‐dose CQ with potential safety hazards (QTc prolongation), especially when taken concurrently with AZ and oseltamivir |

| Chorin et al 11 | United States |

Retrospective cohort study Safety‐oriented study |

84 |

Unknown Moderate to severe |

HCQ + AZ (dosages not available) | QTc prolongation >500 ms in 11% patients; no torsade de pointes |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AZ, azithromycin; CQ, chloroquine; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; ICU, intensive care unit; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Results as presented in the study, considering that the majority has not been peer reviewed yet.

Drug 1: Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is a cheap and readily available decades‐old drug with immunomodulatory properties used to treat autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Its multitude of anti‐inflammatory and immune‐regulatory effects continue to puzzle medical experts worldwide. Pharmacological pathways mainly include the blockage of Toll‐like receptor–mediated signaling (Toll‐like receptor‐7 and ‐9, the endosomal innate immune sensor capable of detecting single‐stranded RNA), the modulation of complement‐dependent antigen/antibody reactions, the activation of T‐regulatory cells, and the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production such as interleukin‐6, tumor necrosis factor‐α and interferon‐γ. 12 Therefore, hydroxychloroquine immediately appeared attractive to attenuate the inflammatory response directed against SARS‐CoV‐2 that results in the cytokine storm, which is held responsible for severe COVID‐19 presentations.

The processes of SARS‐CoV‐2 replication with the resulting pulmonary epithelial and endothelial cell injury and angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐2 (ACE2) downregulation and shedding rapidly result in exuberant inflammatory responses, evidenced by increasing plasma concentrations of various cytokines including interleukin‐6. Hydroxychloroquine‐mediated inhibition of interleukin‐6 production has been well established in vitro on peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated by phytohemagglutinin or lipopolysaccharide. 13 Its benefit in counteracting the inflammatory rheumatologic disease activity is well correlated in vivo with the resulting lowering effects on most cytokines and proinflammatory markers. 14 Therefore, since interleukin‐6 plays a key starter role in COVID‐19–related cytokine storm, hydroxychloroquine rapidly appeared, at least theoretically, as a potential immunomodulatory anti–COVID‐19 drug, if administered early enough in the disease time course.

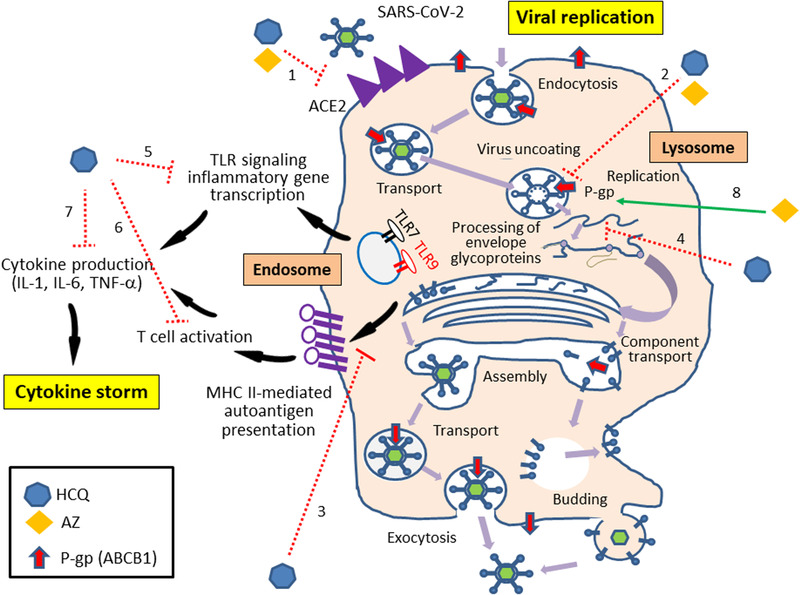

The 4‐aminoquinoline compounds are active in vitro against a range of viruses with different suggested mechanisms of action. Recently, hydroxychloroquine‐attributed anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 activity was established in vitro (50% effective concentration [EC50] = 0.72 μmol/L at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 [100 PFU/well] in Vero cells for 2 hours) and found more potent than chloroquine (EC50 = 5.47 μmol/L in the same conditions). 15 However, the mechanisms of hydroxychloroquine‐attributed anti–COVID‐19 activity remain presumptive (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Suggested mechanisms for the antiviral and immunomodulatory activities of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in COVID‐19 highlighting possible synergic effects between the 2 drugs if prescribed in combination (adapted from Savarino et al, 34 with permission). Possible hydroxychloroquine‐attributed effects include (1) interference with ACE2 glycosylation and reduction of viral binding, (2) endosome and lysosome alkalization limiting viral uncoating and assembly, (3) alteration of antigen processing and MHC class II–mediated autoantigen presentation, (4) disruption of RNA interaction with TLRs and nucleic acid sensors, (5) inhibition of proinflammatory genes transcription, (6) inhibition of T‐cell activation, and (7) inhibition of cytokine production. Possible azithromycin‐attributed effects include (1) interference with ACE2 and reduction of viral binding, (2) endosome and lysosome alkalization limiting viral uncoating and assembly, and (3) role of lysosomal P‐glycoprotein that enhances intralysosomal concentrations of azithromycin. ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; AZ, azithromycin; COVID‐19, coronavirus 2019 disease; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IL, interleukin; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein; RNA, ribonucleic acid; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α; TLR, Toll‐like receptor.

In addition to the previously reported immunomodulatory action, hydroxychloroquine may alter ACE2 glycosylation, blocking SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with its membrane receptor and subsequently the virus/host cell membrane fusion. 16 Consistent with the hypothesis of ACE2 interaction, chloroquine was shown to inhibit quinone reductase‐2, a structural neighbor of UDP‐N‐acetylglucosamine‐2‐epimerases, involved in sialic acid biosynthesis. Although deserving deeper investigations, this molecular mechanism is considered to mediate antimalarial drug activity in vitro on various viruses such as HIV, SARS‐CoV‐1, and orthomyxoviruses. 16 , 17 However, when discussing any potential benefits of interacting with the ACE/ACE2 system, we should acknowledge that the clinical effects of ACE inhibitors in patients with COVID‐19 still remain controversial. These drugs may appear attractive to treat cardiovascular diseases by reducing pulmonary inflammation; however, their use may be accompanied by enhanced ACE2 expression that facilitates the viral invasion. 18

Interestingly, as a weak base, hydroxychloroquine increases the intracellular pH, mainly in the acidic organelles such as endosomes/lysosomes (pH 4.5) where it intensively accumulates. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine alkalinizes the phagolysosomes (pH ∼6.5; known as the lysozomotropic activity) and may thus inhibit the viral cleavage mediated by pH‐dependent proteases, disrupt the fusion process and stop the viral replication. These last effects complete the wide pharmacological target spectra of hydroxychloroquine in COVID‐19.

Finally, in antigen‐presenting cells, hydroxychloroquine prevents antigen processing and subsequently T‐cell activation, differentiation, and cytokine production. 19 , 20 At the molecular level, hydroxychloroquine acts by (1) altering the digestion pattern of the antigenic peptides, (2) retarding the major histocompatibility complex class II α and β chains from forming a stable compact complex with the antigenic peptide due to the diminished degradation of the nonpolymorphic invariant chain, and (3) altering the recycling of α‐β‐peptide complexes from the cell surface. 19 , 20

To date, there is no definitive evidence that all these potential antiviral activities could be achieved by the usual hydroxychloroquine doses (400‐600 mg daily) that are considered clinically safe, as initially suggested. 15 The exact clinically effective hydroxychloroquine dose is still undetermined. Given the weaknesses of Gautret's 1 and Chen's 2 studies along with the negative results of the recently released US veterans study 5 (Table 1), improving effectiveness by increasing hydroxychloroquine doses has been questioned by different modeling approaches including a physiologically based pharmacokinetic study 15 and a pharmacokinetic/virology/QT model. 21 Both studies concluded that hydroxychloroquine doses >400 mg twice daily for at least 5 days are needed to ensure efficacy on viral load decline and cardiac safety. Moreover, the last study highlighted that suboptimal dosing is not efficient on viral load resulting in wasted time and resources. Several trials like the PATCH study (see clinicaltrials.gov) are currently investigating higher doses up to 600 mg twice daily, mainly for the sickest patients. Another major issue also remains the time in the disease course at which the treatment is initiated since, based on the reported antiviral or immunomodulatory mechanisms of action, expected benefits may be reached only if hydroxychloroquine is started early.

Drug 2: Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antimicrobial agent with established antiviral properties in vitro and anti–SARS‐CoV‐2 activity (EC50 of 2.12 μmol/L). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain its antiviral effects (see review; Figure 1). 22 Similarly to hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin is highly trapped in the subcellular acidic organelles such as lysosomes, 23 causing even more severe impairment of acidification. Additionally, azithromycin is responsible for a global amplification of the host's interferon pathway‐mediated antiviral responses. Finally, it may alter SARS‐CoV‐2 entry by interfering between its spike protein and host ACE2 receptor. Very recently, an energetics‐based modeling provided high binding affinity for azithromycin at the interaction point between SARS‐CoV‐2 spike and ACE2, whereas hydroxychloroquine appeared ineffective to directly inhibit this interaction. 24

Clinical studies have shown the ability of azithromycin to reduce the viral load with demonstrated benefits on patient outcome including accelerated recovery (influenza A infection), reduced respiratory morbidity (respiratory syncytial virus and SARS infections) and improved mortality (Middle East respiratory syndrome–coronavirus infection). 22 Several trials in addition to those testing the hydroxychloroquine‐azithromycin combination are currently ongoing to investigate the anti–COVID‐19 benefits of azithromycin alone or in combination with other drugs, focusing as end points not only on viral load but also on clinical outcomes.

Interestingly, azithromycin is a known substrate of P‐glycoprotein (ABCB1), a member of the adenosine triphosphate–binding cassette transporters superfamily, highly expressed and oriented from the cytosolic to the internal side of the lysosome membrane. 25 Therefore, we hypothesized that azithromycin accumulates more intensively under the ABCB1 trapping effect inside the lysosomes and like hydroxychloroquine, reduces lysosomal acidity and exhibits its antiviral properties. Consistently with our hypotheses, synergistic in vivo and in vitro properties have been attributed to the azithromycin/chloroquine combination, used to protect against malaria and treat sexually transmitted infections. 26 , 27 Similarly, the antiviral synergy of the azithromycin/hydroxychloroquine combination was observed in vitro at concentrations achieved in vivo and detected in pulmonary tissues 28 and was shown to accelerate viral clearance in humans in comparison to hydroxychloroquine alone. 1 Thus, azithromycin ABCB1‐dependent lysosomal sequestration plus hydroxychloroquine is very likely an optimal combination to hamper the low‐pH–dependent steps of viral replication and limit COVID‐19 progression. Future clinical studies investigating the azithromycin/chloroquine combination have to focus on clinical outcome improvement and not only viral load reduction, although this target may also be interesting to limit interhuman contagiousness.

Risks‐Benefits of Combining the 2 Drugs

Fears may emerge from increased risks of QT interval prolongation (resulting from the human Ether‐à‐go‐go‐Related Gene potassium channel blockage), torsade de pointes, and cardiovascular death. 29 Despite potential risks acknowledged to be limited if either drug is prescribed singly, 30 , 31 drug‐drug interaction resulting from their coadministration as well as patients’ advanced age, preexisting comorbidities, and COVID‐19–related myocardial and kidney injuries represent challenging conditions. Interestingly, a recent multinational, network cohort, and self‐controlled case series study supported the safety of short‐term hydroxychloroquine treatment but highlighted the risks of heart failure and cardiovascular mortality when combining hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, potentially due to synergistic effects on QT length. 32 Data from recent COVID‐19 trials clearly reported increased adverse events with hydroxychloroquine, especially at high doses and in combination with azithromycin. 9 , 10 , 11 Additionally, extending prescriptions to mildly infected patients is also at risk of misuse and overdose. Clinical toxicologists remember the 1982 suicide outbreak in France following the publication of Suicide: A How‐To Guide, which promoted chloroquine ingestion to complete suicide, 33 resulting in a major crisis of fatalities attributed to chloroquine poisonings.

In patients with COVID‐19 treated with the azithromycin/hydroxychloroquine combination, physicians should be cautious when coprescribing QT interval–prolonging drugs (enhanced toxicity) or P‐glycoprotein substrates/inhibitors (reduced effectiveness). Nevertheless, abandoning azithromycin may importantly limit hydroxychloroquine‐attributed effectiveness. Therefore, well‐designed randomized, double‐blind and placebo‐controlled clinical trials are awaited to evaluate the exact synergy/toxicity balance of this potentially lifesaving combination. Appropriate statistical hypotheses should be formulated when designing the study so that the alternative hypothesis can be inferred upon the rejection of the null hypothesis. Observational studies are not sufficient in nature to meet regulatory requirements and decide if a treatment with potentially serious toxicity should be advocated. Pharmacovigilance departments and poison control centers should be alert to collect all useful toxicological exposure data and trends to guide public health response.

In conclusion, both hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin are friends and foes, when considering the balance issue between the expected synergistic effectiveness to clear the virus from the body and the safety concerns to avoid possible risks of cardiotoxicity when the 2 drugs are combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID‐19 patients with at least a six‐day follow up: A pilot observational study [published online ahead of print April 11, 2020]. Travel Med Infect Dis. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Z, Hu J, Zhang Z, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID‐19: results of a randomized clinical trial. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758v2.full.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 3. Chen J, Danping L, Li L, et al. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with common coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19). J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020; 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03. http://www.zjujournals.com/med/EN/10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03. Accessed April 28, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Molina JM, Delaugerre C, Goff JL, et al. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID‐19 infection [printed online ahead of print March 30, 2020]. Med Mal Infect. 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, Cummings T, Hardin JW, Sutton SS, Ambati J. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with Covid‐19. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920v1.article-metrics. Accessed April 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Mahévas M, Tran VT, Roumier M et al. No evidence of clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalised for COVID‐19 infection and requiring oxygen: results of a study using routinely collected data to emulate a target trial. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.10.20060699v1. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 7. Million M, Lagier JC, Gautret P et al. Early treatment of 1061 COVID‐19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, Marseille, France. https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/MS.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Barbosa J, Kaitis D, Freedman R, Le K, Lin X. Clinical outcomes of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19: a quasi‐randomized comparative study. Bibliovid. 2020. https://bibliovid.org/clinical-outcomes-of-hydroxychloroquine-in-hospitalized-patients-with-covid-19-a-302 Accessed April 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang W, Cao Z, Han M et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID‐19: an open‐label, randomized, controlled trial. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.10.20060558v1. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 10. Borba MGS, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, et al. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection ‐ a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chorin E, Dai M, Shulman E, et al. The QT interval in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin. The QT interval in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.02.20047050v1. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 12. Wallace DJ, Gudsoorkar VS, Weisman MH, Venuturupalli SR. New insights into mechanisms of therapeutic effects of antimalarial agents in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:522‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van den Borne BE, Dijkmans BA, de Rooij HH, le Cessie S, Verweij CL. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine equally affect tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, interleukin 6, and interferon‐gamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(1):55‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Willis R, Seif AM, McGwin G Jr, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine treatment on pro‐inflammatory cytokines and disease activity in SLE patients: data from LUMINA (LXXV), a multiethnic US cohort. Lupus. 2012;21:830‐835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) [printed online ahead of print March 9, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Savarino A, Di Trani L, Donatelli I, Cauda R, Cassone A. New insights into the antiviral effects of chloroquine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:67‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1653‐1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ziegler HK, Unanue ER. Decrease in macrophage antigen catabolism caused by ammonia and chloroquine is associated with inhibition of antigen presentation to T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:175‐178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nowell J, Quaranta V. Chloroquine affects biosynthesis of Ia molecules by inhibiting dissociation of invariant (gamma) chains from alpha‐beta dimers in B cells. J Exp Med. 1985;162:1371‐1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garcia‐Cremades M, Solans BP, Hughes E, et al. Optimizing hydroxychloroquine dosing for patients with COVID‐19: An integrative modeling approach for effective drug repurposing [printed online ahead of print April 14, 2020]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020. 10.1002/cpt.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Damle B, Vourvahis M, Wang E, Leaney J, Corrigan B. Clinical pharmacology perspectives on the antiviral activity of azithromycin and use in COVID‐19 [printed online ahead of print April 17, 2020]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 10.1002/cpt.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Togami K, Chono S, Morimoto K. Subcellular distribution of azithromycin and clarithromycin in rat alveolar macrophages (NR8383) in vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:1494‐1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandeep S, McGregor K. Energetics based modeling of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin binding to the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike (S) protein–ACE2 complex. https://chemrxiv.org/articles/Energetics_Based_Modeling_of_Hydroxychloroquine_and_Azithromycin_Binding_to_the_SARS-CoV-2_Spike_S_Protein_-_ACE2_Complex/12015792. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 25. Andreania J, Le Bideau M, Duflot I, et al. In vitro testing of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS‐CoV‐2 shows synergistic effect. https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/pre-prints-ihu/. Accessed April 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Pereira MR, Henrich PP, Sidhu AB, et al. In vivo and in vitro antimalarial properties of azithromycin‐chloroquine combinations that include the resistance reversal agent amlodipine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3115‐3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chico RM, Chandramohan D. Azithromycin plus chloroquine: combination therapy for protection against malaria and sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:1153‐1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seral C, Michot JM, Chanteux H, Mingeot‐Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. Influence of P‐glycoprotein inhibitors on accumulation of macrolides in J774 murine macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1047‐1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. US Food & Drug Administration . FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID‐19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-cautions-against-use-hydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 30. Howard PA. Azithromycin‐induced proarrhythmia and cardiovascular death. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1547‐1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGhie TK, Harvey P, Su J, Anderson N, Tomlinson G, Touma Z. Electrocardiogram abnormalities related to anti‐malarials in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:545‐551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lane JCE, Weaver J, Kostka K et al. Safety of hydroxychloroquine, alone and in combination with azithromycin, in light of rapid wide‐spread use for COVID‐19: a multinational, network cohort and self‐controlled case series study. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.08.20054551v1. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 33. Guillion C, Le Bonniec Y. Suicide mode d'emploi. Histoire, technique, actualite. Paris: Alan Moreau Editions; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:722‐727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]