Abstract

Objective

Macrophage interleukin (IL)-10 signalling plays a critical role in the maintenance of a regulatory phenotype that prevents the development of IBD. We have previously found that anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibodies act through Fcγ-receptor (FcγR) signalling to promote repolarisation of proinflammatory intestinal macrophages to a CD206+ regulatory phenotype. The role of IL-10 in anti-TNF-induced macrophage repolarisation has not been examined.

Design

We used human peripheral blood monocytes and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages to study IL-10 production and CD206+ regulatory macrophage differentiation. To determine whether the efficacy of anti-TNF was dependent on IL-10 signalling in vivo and in which cell type, we used the CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer model in combination with several genetic mouse models.

Results

Anti-TNF therapy increased macrophage IL-10 production in an FcγR-dependent manner, which caused differentiation of macrophages to a more regulatory CD206+ phenotype in vitro. Pharmacological blockade of IL-10 signalling prevented the induction of these CD206+ regulatory macrophages and diminished the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF therapy in the CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer model of IBD. Using cell type-specific IL-10 receptor mutant mice, we found that IL-10 signalling in macrophages but not T cells was critical for the induction of CD206+ regulatory macrophages and therapeutic response to anti-TNF.

Conclusion

The therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF in resolving intestinal inflammation is critically dependent on IL-10 signalling in macrophages.

Keywords: IBD basic research, TNF, antibody targeted therapy, infliximab, interleukins

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Intestinal immune tolerance depends on interleukin (IL)-10 signalling in lamina propria macrophages to maintain a regulatory CD206+ regulatory phenotype.

The effect of anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in IBD depends on Fcγ-receptor signalling.

Fcγ-receptor (FcγR) signalling induces IL-10 production in macrophages.

What are the new findings?

Anti-TNF therapy induces FcγR-dependent IL-10 production in mouse and human macrophages in vitro.

Anti-TNF therapy polarises human and mouse macrophages towards CD206+ macrophages in an IL-10-dependent manner in vitro.

The efficacy of anti-TNF therapy in the T-cell transfer model of colitis depends on IL-10 signalling, specifically in macrophages and not T cells.

Anti-TNF therapy induces IL-10 production and polarises macrophages towards CD206+ regulatory macrophages in intestinal biopsies of patients with Crohn’s disease in vivo, specifically in anti-TNF responders in contrast to non-responders.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future ?

Our results point to a central role for IL-10-induced repolarisation of macrophages to a regulatory phenotype in the therapy of patients with IBD.

A reduced response to IL-10 contributes to primary non-response to anti-TNF in IBD and might be used to identify such patients.

Introduction

Despite the considerable efficacy of antitumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in the treatment of IBD, up to 30% of patients with IBD do not respond, and it is unknown what causes this primary non-reponse.1 This uncertainty is in part related to the fact that the mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy in IBD has not been fully elucidated.2 The mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy in IBD cannot solely be attributed to the neutralisation of TNF alone, as some TNF-neutralising drugs, such as etanercept, are successful in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis3 4 but do not show efficacy in IBD.5 6 Recently, it has been shown that high oncostatin M (OSM) levels are associated with the non-response to anti-TNF in IBD.7

Interleukin (IL)-10 is a cytokine with convincing evidence for a role in the pathogenesis of IBD. IL-10 is linked to the aetiology of IBD through multiple genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and both mice and humans develop spontaneous IBD when IL-10 or its receptors are genetically disrupted.8–11 It has previously been established that the role of IL-10 in IBD depends on IL-10 signalling in macrophages. Here IL-10 acts to maintain lamina propria macrophages in a regulatory CD206+ phenotype that is critical to maintain intestinal immune tolerance.12 13 Interestingly, it has previously been described that IL-10 mutant mice are refractory to anti-TNF therapy, whereas they are highly responsive to antibodies to IL-12/IL-23p40.14 It is currently not known why IL-10 mutant mice are refractory to anti-TNF. Perhaps IL-10 mutant mice display a type of inflammation that develops independently of an intervention with anti-TNF. Alternatively and more intriguingly, there is a possibility that IL-10 signalling is required for the mechanism of action of anti-TNF.

We have previously shown that full monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against TNF engage Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) and that this Fc–FcγR interaction is necessary for the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF in a preclinical model of IBD. Mice without activating FcγRs completely lost response to anti-TNF therapy in the T-cell transfer colitis model, and conversely, a hypofucosylated anti-TNF antibody with increased Fc-binding affinity showed improved efficacy.15 16 Additionally, we have shown that anti-TNF skews human monocytes towards CD206+ regulatory macrophages in an Fc-dependent manner in vitro17 and in vivo,16 and that the response to anti-TNF therapy in both mice and humans was accompanied by the formation of these CD206+ regulatory macrophages in the intestine.16 18 However, the exact signalling mechanism of the induction of these macrophages and their precise role in the resolution of intestinal inflammation on anti-TNF therapy are currently unknown.

Interestingly, it has previously been shown that FcγR signalling in macrophages increases the secretion of IL-10.19–21 Given the crucial role of macrophage IL-10 signalling in specifying an M2-like CD206+ regulatory macrophage phenotype to prevent intestinal inflammation,12 13 the dependence of response to anti-TNF on FcγR signalling16 and the observation that IL-10 mutant mice are refractory to anti-TNF, we decided to examine the role of IL-10 signalling in the therapeutic response to anti-TNF.

Here we show that anti-TNF mAb therapy increases IL-10 production in monocytes/macrophages in an FcγR-dependent manner in vitro, which skews them towards a CD206+ regulatory phenotype. Using cell type-specific mutant mice, we find that IL-10 signalling in macrophages is absolutely required for anti-TNF-induced macrophage skewing to a CD206+ regulatory phenotype as well as therapeutic response.

Materials and methods

For information on mice strains and materials used, in situ hybridisation, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, in vitro experiments and the quantification of proteins by western blot or ELISA, see online supplementary information.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp001.pdf (158.4KB, pdf)

Mouse experiments

The T-cell transfer model was performed as previously described.22 Colitis was induced by injecting 3–5×105 CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells intraperitoneally, with mice without a transfer as controls. Il10KO animals were treated with anti-mouse TNF, anti-mouse IL-12/23-p40 or isotype control mAbs, 300 µg, two times per week intraperitoneally from 8 to 14 weeks of age. The anti-TNF dose titration was described previously.23 The effective dosage of 100 µg anti-TNF twice a week intraperitoneally was used for all further experiments from 3 weeks after the T-cell transfer, when animals began to exhibit clinical signs of colitis, until the end of the experiments. The T-cell transfer experiment with the FcgRKO/Rag1KO animals was described previously.16 The anti-IL-10Rα antibody was administered from 2 weeks after the T-cell transfer, 250 µg two times a week intraperitoneally until the end of the experiment. The Mouse Colitis Endoscopy Index (MCEI) and the Mouse Colitis Histology Index (MCHI) were determined as recently described.24 All experiments were approved by the Academic Medical Center (AMC)

Cohort studies of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD)

Intestinal biopsies were collected from patients with CD before and during anti-TNF treatment (online supplementary table 1). Seven responders and seven non-responders, with response defined as a decrease of >25% Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index for severity (CDEI) or Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD), were included. The study protocols were approved by the medical ethical committee of the Amsterdam UMC and of the University Hospital in Leuven, and all participants provided written informed consent.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp002.pdf (55.4KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as bar–scatter plots with bars indicating median and dots representing individual values/animals, or bar graphs representing mean+SEM. Data were analysed by GraphPad Prism V.7.02 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) with statistical tests specified in the figure legends. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

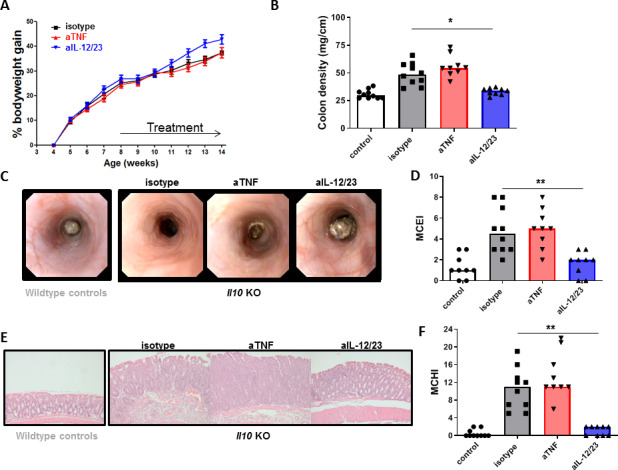

Colitis in Il10KO mice is resistant to anti-TNF therapy

As previously described,14 we found that chronic intestinal inflammation in the Il10KO mouse was highly responsive to IL-12/23 therapy but completely resistant to anti-TNF therapy. In contrast to anti-TNF, treatment with the anti-IL-12/23 antibody improved bodyweight (figure 1A), colon density (figure 1B), endoscopic severity of disease (figure 1C, D) and the histology score (figure 1E, F) when compared with isotype control treatment. The absence of a therapeutic effect of anti-TNF in the Il10KO mouse led us to hypothesise that IL-10 is a necessary factor for the induction of a therapeutic response to anti-TNF therapy.

Figure 1.

Il10KO mice are anti-TNF refractory. Il10KO mice were treated with 300 µg anti-TNF (n=9), anti-IL-12/23 (n=9) or isotype control (n=10) two times per week for 6 weeks as described in the Materials and methods section (healthy control mice (n=10) were included in B–F. (A) Body weight, (B) colon density, (C) representative endoscopy images and (D) endoscopy score (MCEI). (E) Representative images of H&E-stained intestinal slides (E) and (F) histology score (MCHI). Significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. IL, interleukin; MCEI, Mouse Colitis Endoscopy Index; MCHI, Mouse Colitis Histology Index; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

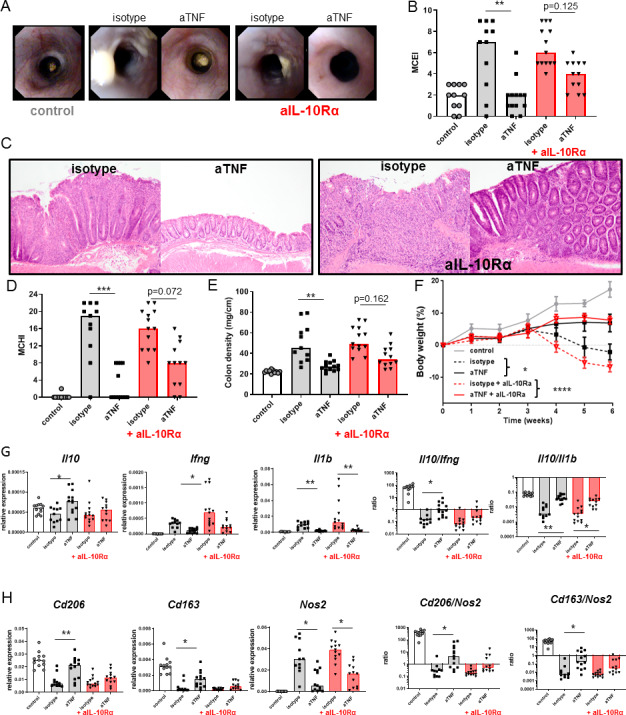

Blocking IL-10 signalling reduces the efficacy of anti-TNF therapy

Since Il10KO mice lack IL-10 since conception, it is not clear if lack of response to anti-TNF is related to developmental abnormalities of different immune cell subsets or due to the absence of IL-10 signalling during therapy. To investigate if IL-10 is a crucial factor for the efficacy during anti-TNF therapy, we coadministered an anti-IL-10Rα antibody in the T-cell transfer model. The anti-IL-10Rα diminished the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF, indicated by the absence of a significant improvement of the endoscopy score (figure 2A, B), the histology score (figure 2C, D) and colon density (figure 2E). Interestingly, it did not affect the effect of the anti-TNF on body weight loss (figure 2F), indicating that body weight loss is dependent on the well-established cachectic effects of circulating TNF, which we have seen before,15 that are less dependent on IL-10. There was an increase in intestinal Il10 expression on treatment with anti-TNF, especially when Il10 levels were expressed relative to levels of key proinflammatory cytokines, such as Ifng or Il1b (figure 2G). The induction of Il10 was reduced by blocking IL-10 signalling, indicating a positive feedback mechanism. Anti-TNF therapy increased the expression of Cd163 and Cd206, two markers of regulatory macrophages, in an IL-10 dependent manner, and reduced the expression of Nos2, a marker of proinflammatory macrophages, independent of IL-10 (figure 2H). The increased ratios of Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 are, although somewhat artificial, a good indication that anti-TNF shifts the intestinal macrophage balance towards the regulatory phenotype in an IL-10 dependent manner. Together, these data suggest that IL-10 signalling is directly required for the full therapeutic response to anti-TNF in IBD.

Figure 2.

The efficacy of anti-TNF is IL-10 dependent. Severe combined immunedeficient (SCID) animals received 3×105 CD4+CD45Rbhigh T cells and were treated with an anti-IL-10Rα (250 µg two times per week) from 2 weeks after the T-cell transfer, in combination with isotype or anti-TNF (100 µg two times per week) from 3 weeks after the T-cell transfer. Representative stills of endoscopy movies (A) scored for the MCEI in (B). Representative images of H&E-stained intestinal slides (C) scored for the MCHI in (D), the colon density in (E) and the bodyweight gain/loss during the experiment in (F). Intestinal expression levels of Il10, Ifng and Il1b relative to Gapdh and Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios, determined on whole-colon mRNA, are shown (G). (H) Expression levels of Cd206, Cd163 and Nos2 relative to Gapdh and Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 ratios. All significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test (n=11–13). Asterisks in (F) indicate comparison between anti-TNF and isotype (*, p<0.05) and between isotype +anti-IL10Rα and anti-TNF +anti-IL10Rα (****, p<0.0001). IL, interleukin; MCEI, Mouse Colitis Endoscopy Index; MCHI, Mouse Colitis Histology Index; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and **** p<0.0001.

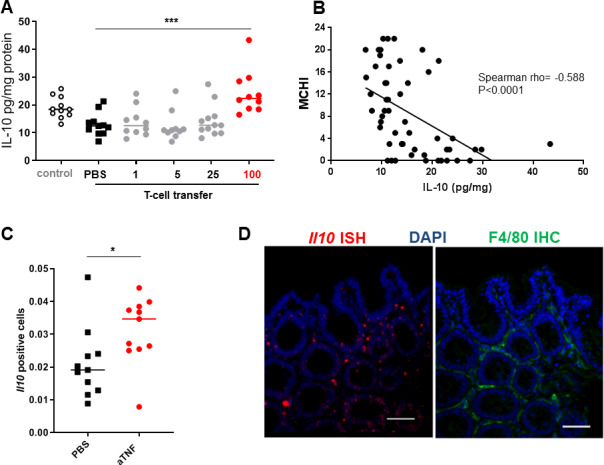

Intestinal IL-10 is increased upon successful anti-TNF therapy

We have previously shown that the T-cell transfer colitis model responds to anti-TNFmAb therapy in a dose-dependent fashion.23 In this titration experiment, intestinal IL-10 levels were increased in animals treated with the effective dosage of anti-TNF (figure 3A). There was an association between intestinal IL-10 levels and the response to anti-TNF therapy, shown by the strong inverse correlation between the intestinal IL-10 level and the MCHI (Spearman’s rho=−0.582, p<0.0001; figure 3B). To investigate which cells are responsible for the production of IL-10 on anti-TNF therapy, we performed in situ hybridisation. Anti-TNF therapy led to an increase of Il10 transcripts in CD3-negative cells in the intestine (figure 3C). Immunohistochemical analysis of the macrophage marker F4/80 on consecutive slides strongly suggests that anti-TNF increases Il10 specifically in macrophages (figure 3D), although we cannot exclude expression in other cell types.

Figure 3.

Anti-TNF therapy increases intestinal IL-10 levels. IL-10 levels in whole-colon homogenates of severe combined immunedeficient (SCID) mice that received a CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer and were treated with different dosages of anti-TNF (n=10–12) for 4 weeks from 3 weeks after the T-cell transfer. Animals treated with a therapeutic dosage of anti-TNF (100 μg) are shown in red (A). (B) Correlation between intestinal IL-10 levels and the histological score (MCHI) in all mice that received a T-cell transfer (n=53). The proportion of CD3-negative lamina propria cells expressing Il10 was determined by image analysis (C, n>10 images/condition, n=11 per group) as determined by fluorescent in situ hybridisation. (D) Representative Il10 in situ hybridisation (red) with F4/80 immunohistochemical staning (green) on a consectutive intestinal tissue slide of an anti-TNF-treated animal. Scale bar is 50 µm. Significance was determined by analysis of variance followed by Sidak’s post hoc in (A) and Mann-Whitney test in (D) with* p<0.05 and ***p<0.001. DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-fenylindool; IHC immunohistochemistry; IL, interleukin; ISH, in situ hybridisation; MCHI, Mouse Colitis Histology Index; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

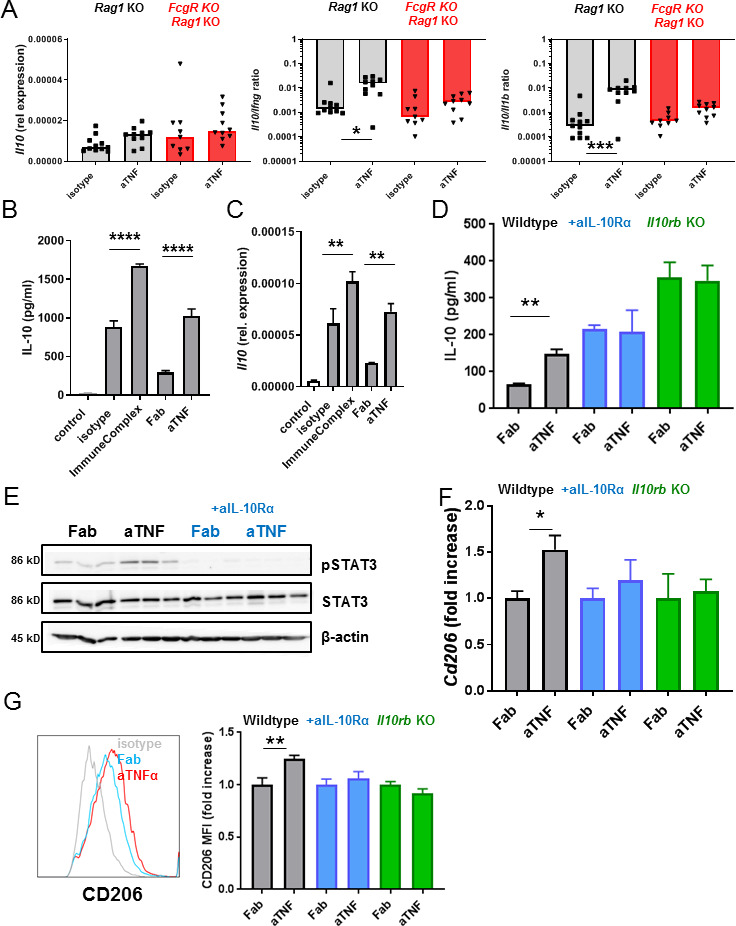

Anti-TNF induces IL-10 signalling through FcγR

In previous studies, we have shown that FcγR interaction is crucial for the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF in IBD, presumably through the induction of regulatory macrophages.15–17 As FcγR ligation is a potent inducer of IL-10 in macrophages,19–21 we investigated Il10 expression in the T-cell transfer model in FcgRKO/Rag1KO animals that are refractory to anti-TNF therapy.16 The intestinal increase in the Il10/Ifng or Il10/Il1b ratio by anti-TNF mAbs was indeed FcγR dependent, as this increase was abrogated in mice that lacked all activating FcγRs (figure 4A). This supports the hypothesis that production of IL-10 is FcγR dependent. To further investigate if anti-TNF can induce IL-10 production in macrophages, we performed in vitro experiments in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). To distinguish the effect of increased FcγR signalling by the anti-TNF mAb versus the neutralisation of TNF alone, we generated Fab fragments of the anti-TNF mAb (online supplementary figure S1). As shown in figure 4B in lipopolysacharide (LPS)-stimulated BMDM immune complexes of the IgG2a control antibody increased the secretion of IL-10, as described.19 Neutralisation of TNF by the anti-TNF Fab reduces the secretion of IL-10, while the anti-TNF mAb significantly increased IL-10 secretion compared with the anti-TNF Fab fragment (figure 4B). This correlated with increased transcription of Il10 (figure 4C), while there was little to no effect on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines like Il1b, Il6 or Tnfa itself (online supplementary figure S2). Anti-TNF mAbs did not increase IL-10 production in FcgRKO BMDMs, confirming the dependence on FcγR signalling (online supplementary figure S3). The induction of IL-10 could be blocked by the anti-IL-10Rα antibody and was absent in Il10rbKO BMDMs (figure 4D), suggesting an autocrine positive feedback mechanism. IL-10 mediates its signalling activity through the activating phosphorylation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3.25 Incubation with the anti-TNF mAb indeed led to IL-10-dependent phosphorylation of STAT3 in BMDMs (figure 4E). As we hypothesised that anti-TNF mAbs induce the differentiation of regulatory-type macrophages, through increased IL-10 signalling, we determined the effect on Cd206. Incubation with the anti-TNF mAb indeed led to increased expression of Cd206, which was fully dependent on IL-10 signalling (figure 4F). This was confirmed by flow cytometry for CD206 (figure 4G). These results propose that anti-TNFmAb-induced FcγR signalling increases IL-10 production in macrophages, which subsequently enables differentiation to a more regulatory phenotype.

Figure 4.

Anti-TNF induces IL-10-dependent M2 differentiation in BMDMs in vitro. (A) Intestinal Il10 expression level relative to Gapdh and Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios of the Rag1 KO and FcgRKO/Rag1KO animals treated with anti-TNF. Relative Ifng and Il1b expression levels were reported in Bloemendaal et al.16 Significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test, n=9–11. (B) IL-10 levels in medium of BMDMs stimulated with lipopolysacharide (LPS,100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) in combination with the IgG isotype control antibody (10 µg mL), IgG immune complex (10 µg mL), the anti-TNF mAb (10 µg/mL) or Fab fragment (7.2 µg/mL) after 48 hours (B). (C) Levels of Il10 normalised for Gapdh expression in BMDMs after 24 hours. (D) IL-10 levels in medium of BMDMs (after 48 hours). (E) Western blot for pSTAT3, STAT3 and β-actin. (F) Levels of Cd206 normalised for Gapdh expression after 48 hours in (G) Representative histogram of flow cytometry for CD206, expressed as fold increase of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in graph on BMDMs after 72 hours. Wild-type BMDMs are shown in black, wild-type BMDMs incubated with anti-IL-10Rα (10 µg/mL) in blue and Il10rbKO BMDMs in green. All data represent mean+SEM (n=3–6), representative of two to three independent experiments. Significance was determined by analysis of variance. followed by Sidak’s post hoc test (B, C) or unpaired t-test with *p<0.05, **p<0.01,***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001. BMDM, bone marrow-derived macrophage; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp003.pdf (78.1KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp004.pdf (54.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp005.pdf (48.3KB, pdf)

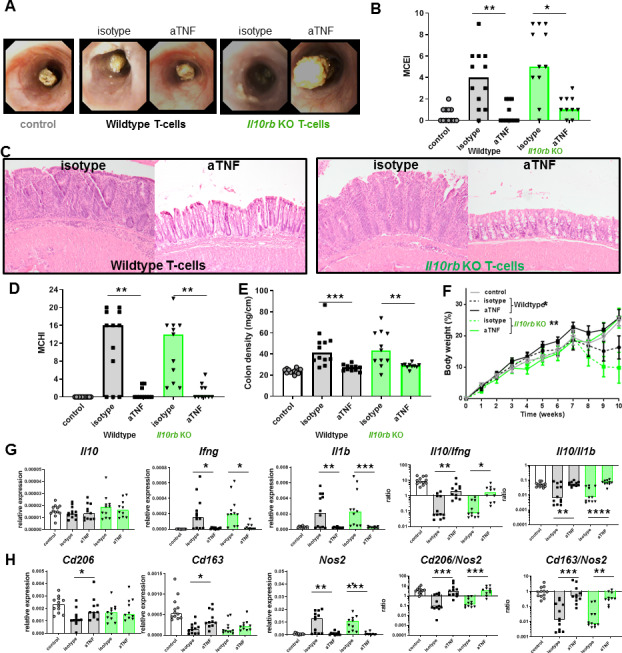

IL-10 signalling in Tcells is dispensable for the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF

To exclude the possibility that the immunosuppressive effect of anti-TNF therapy is mediated through a direct effect of increased IL-10 levels on T-cells in vivo, we adoptively transferred CD4+CD45Rbhigh Il10rb KO Tcells into Rag1KO mice. Anti-TNF mAb therapy caused a similar reduction in the endoscopy score (figure 5A, B), histology score (figure 5C, D) and colon density (figure 5E) in Rag1KO mice that received an adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45Rbhigh Il10rbKO T cells, compared with mice that received wild-type CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cells. This clearly shows that IL-10 signalling in T cells is dispensable for a response to anti-TNF mAb therapy. The absence of IL-10 signalling in T-cells did not alter the anti-TNF mAb-induced increase in the Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratio (figure 5G) or Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 ratios (figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Efficacy of anti-TNF is independent of IL-10 signalling in T-cells. Rag1KO animals received a 3×105 wild type (grey) or 3×105 Il10rbKO (green) CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer and were treated with isotype or anti-TNF. Control Rag1KO animals did not receive a T-cell transfer. Representative stills of endoscopy movies (A) scored for the MCEI in (B). Representative images of H&E-stained intestinal slides (C) scored for the MCHI in (D), the colon density (E) and the bodyweight gain/loss during the experiment in (F). (G) Intestinal expression levels of Il10, Ifng and Il1b relative to Gapdh and Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios, determined on whole-colon mRNA. (H) Expression levels of Cd206, Cd163 and Nos2 relative to Gapdh and Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 ratios. All significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 (n=10–12). IL, interleukin; MCEI, Mouse Colitis Endoscopy Index; MCHI, Mouse Colitis Histology Index; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

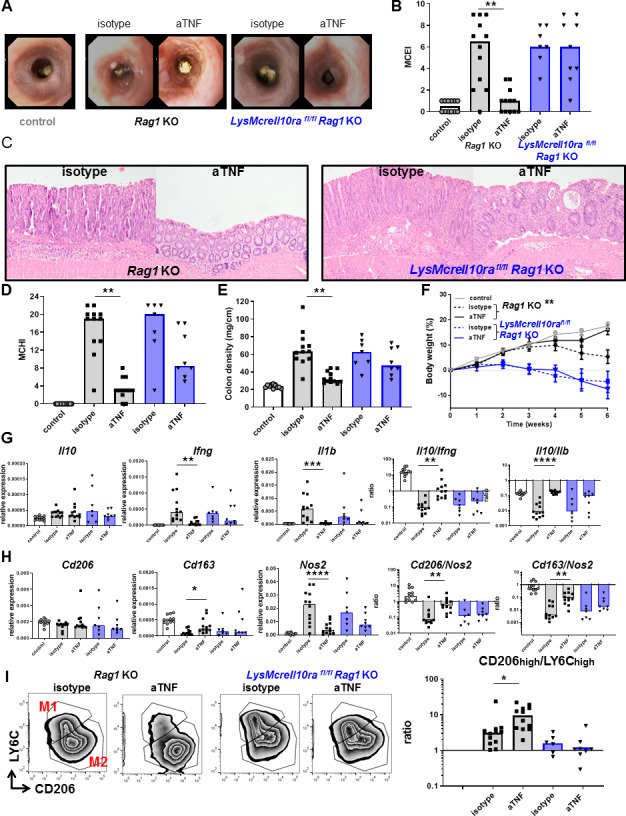

IL-10 signalling in macrophages is necessary for the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF in vivo

To confirm that IL-10 signalling in macrophages is critical for the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF mAbs in IBD, we used LysMCreIl10rafl/flRag1KO mice, in which the IL-10Rα is specifically deleted in macrophages.26 Development of intestinal inflammation in these mice, on a CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer, was completely resistant to anti-TNF mAb therapy. There was no effect of anti-TNF mAb on the endoscopy score (figure 6A, B), histology score (figure 6C, D), colon density (figure 6E) or loss of bodyweight (figure 6F) in mice with a macrophage-specific deletion of IL-10Rα. The resistance to anti-TNF was not associated with decreased levels of anti-TNF mAbs (online supplementary figure S4A) or decreased intestinal Tnfa expression (online supplementary figure S4B). However, the resistance to anti-TNF correlated with the absence of an increase in the intestinal Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratio (figure 6G). Moreover, in contrast to Rag1KO control mice, there was no anti-TNF-dependent increase in Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 (figure 6H) ratios. These ratios correlated very well with the Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios in the intestine (online supplementary figure S5). As the Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 ratios cannot discriminate between depolarisation of macrophages and the infiltration of inflammatory monocytes, we have confirmed by flow cytometry that there indeed was a complete abrogation of anti-TNF mAb-induced regulatory macrophage polarisation in macrophage-specific IL-10Rα mutant mice (figure 6I). Altogether, these data show that macrophage IL-10 signalling is absolutely required for both regulatory macrophage polarisation and therapeutic efficacy in response to anti-TNF mAbs.

Figure 6.

The efficacy of anti-TNF is dependent on IL-10 signalling in macrophages in vivo. Rag1KO (grey) or LysMcreIl10rafl/flRag1KO (blue) animals received a CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer (5×105 cells) and were treated with isotype or anti-TNF. Control animals (Rag1KO) did not receive a T-cell transfer. Representative stills of endoscopy movies (A) scored for the MCEI in (B). Representative images of H&E-stained intestinal slides (C) scored for the MCHI in (D), the colon density (E) and the bodyweight gain/loss during the experiment in (F). (G) Intestinal expression levels of Il10, Ifng and Il1b relative to Gapdh and Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios, determined on whole-colon mRNA. Expression levels of Cd206, Cd163 and Nos2 relative to Gapdh and Cd206/Nos2 and Cd163/Nos2 ratios are shown (H). Flow cytometry analysis for CD206 and LY6C is shown in (I), after gating for colonic macrophages (DAPI−CD45+ CD11b+Ly6G−CD64+). All significance was determined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001, n=7–12. IL, interleukin; Mouse Colitis Endoscopy Index; MCHI, Mouse Colitis Histology Index; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp006.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp007.pdf (31.5KB, pdf)

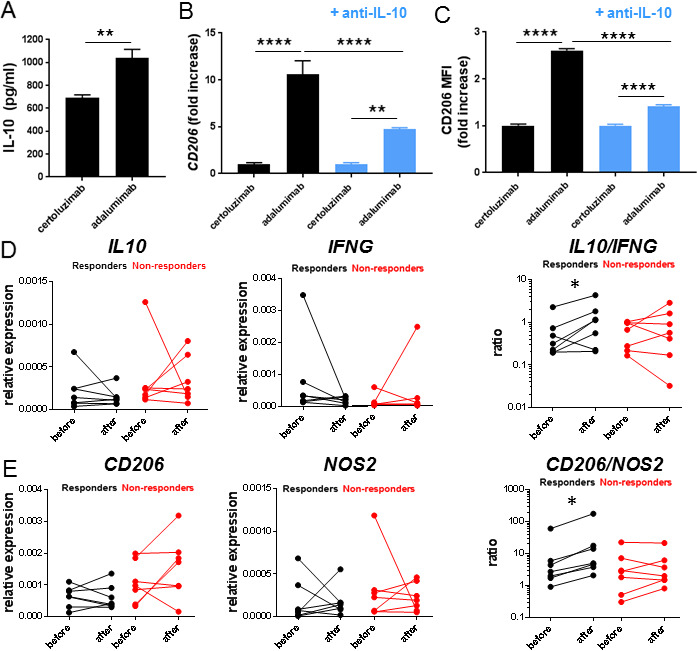

Effect of anti-TNF on IL-10 signalling in human IBD

To investigate whether upregulation of IL-10 and subsequent signalling is relevant for the effect of anti-TNF mAbs in patients with IBD, we first investigated IL-10 production in differentiating human monocytes in vitro. Incubation with the anti-TNF mAb adalimumab lead to the increased production of IL-10 when compared to incubation with the anti-TNF Fab fragment certolizumab (figure 7A), and enabled differentiation to a more regulatory phenotype of macrophage in this in vitro system, characterised by the upregulation of CD206 (figure 7B). This was largely dependent on IL-10 signalling as an anti-IL-10 blocking antibody strongly diminished the upregulation of CD206 (figure 7B). This was confirmed by flow cytometry for CD206 (figure 7C). Finally, we determined mucosal IL10 mRNA levels in patients with CD treated with anti-TNF mAbs. We included seven endoscopic responders and seven endoscopic non-responders (online supplementary table 1). Although there was no increase in relative expression levels of IL10, as with the mice treated with anti-TNF therapy, the IL10/IFNG expression ratios were significantly increased in the responders on anti-TNF treatment, while there was no such increase in anti-TNF non-responders (figure 7D). The induction of regulatory macrophages on anti-TNF mAb therapy, indicated by the increase in the CD206/NOS2 ratio, was also found specifically in anti-TNF responders in contrast to non-responders (figure 7E) and correlated with IL10/IFNG levels (online supplementary figure S6).

Figure 7.

Anti-TNF induces IL-10-dependent M2 differentiation in human monocytes in vitro. IL-10 levels in medium of human monocytes stimulated with lipopolysacharide (LPS,100 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) and the full monoclonal anti-TNF antibody (adalimumab, 10 µg/mL) or anti-TNF Fab fragment (certolizumab, 10 µg/mL) after 48 hours (A) and levels of CD206 normalised for Gapdh after 48 hours or flow cytometry for CD206 expressed as fold increase of MFI after 72 hours (C) in combination with and anti-IL-10 antibody (10 µg/mL) or isotype control (10 µg/mL). All graphs are mean+SEM representative of three independent donors with n=4–6 per condition. The IL10 and IFNG expression levels relative to GAPDH and IL10/IFNG ratios (D) and CD206 and NOS2 expression levels relative to GAPDH and CD206/NOS2 ratios (E) in intestinal biopsies before and after treatment in anti-TNF responding and non-responding patients with CD.Significance was determined by Mann Whitney in A, analysis of variance followed by Holm-Sidak's post hoc test in B andC, and Wilcoxon signed rank test in D and E with *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp008.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

Discussion

The reasons for non-response to anti-TNF therapy in IBD are still poorly understood.1 Here, we show that anti-TNF mAbs require IL-10 signalling in macrophages and that this IL-10 signalling is necessary for anti-TNF-induced polarisation of macrophages to a regulatory M2-like phenotype. Mice in which IL-10 signalling is specifically disrupted in macrophages are completely resistant to treatment with anti-TNF in the CD4+CD45Rbhigh T-cell transfer model of colitis, while disruption of IL-10 signalling in T cells does not affect treatment response.

IL-10 is a key factor in the maintenance of mucosal immunological tolerance. Mice that lack IL-10 develop chronic inflammatory bowel disease.10 In humans, variants in the IL10 locus are associated with the risk of developing IBD in genome-wide association studies8 9 and rare patients that have homozygous mutations in either IL10 or IL10R develop severe early onset IBD.11 Studies in cell type-specific IL-10 signalling-deficient mice, as well as using cells derived from IL-10R-deficient patients have shown that tolerance critically depends on macrophage IL-10 signalling.12 13 It was found that the M2-like CD163/CD206+ regulatory phenotype of mucosal macrophages depends on IL-10 signalling. In the absence of IL-10, macrophages are locked in an M1-like Nos2/CD86+ proinflammatory phenotype and secrete excessive proinflammatory cytokines in response to stimulation. Both mice and patients with germline mutations in the IL-10 pathway fail to respond to therapy with anti-TNF.14 27 This may be due to a developmental abnormality of the immune system causing an inflammatory process in which the mechanism of action of anti-TNFs is irrelevant. Interestingly, data from different mouse models of colitis suggest that TNF may actually have a protective role during intestinal inflammation and that, depending on the context, TNF may even be required to suppress intestinal inflammation in mice.2 For example, neutralisation of TNF with a mAb substantially worsened dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis28 and TNF knock out mice are highly sensitive to DSS.29 The complete absence of TNF worsens colitis in IL-10 mutant mice,30 and in the T-cell transfer model, colitis worsens if the transferred T-cells lack TNF-receptor II (TNFRII).31 Our own previous data have shown that the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF is lost in mice that lack activating FcγRs.16 Together these data suggest that TNF can have important protective functions in intestinal inflammation supporting the notion that anti-TNFs may have additional therapeutic modes of action independent from the neutralisation of TNF. IL-10 signalling may be one of the additional modes of action. Indeed, here we find that pharmacological blockade of IL-10 signalling with an IL-10Rα blocking antibody reduces the therapeutic efficacy of an anti-TNF in the T-cell transfer model of colitis. This strongly suggests that IL-10 signalling is directly required for the therapeutic response to anti-TNF. In line with this, West et al 7 recently showed that systemic IL-10Rα blockade in combination with an Helicobacter hepaticus infection leads to the development of anti-TNF-resistant colitis, which was associated with increased OSM levels. In our hands, the systemic IL-10Rα blockade indeed seemed to increase intestinal Osm levels (online supplementary figure S7A) and was associated with the loss of response to anti-TNF therapy. However, the anti-TNF-resistant colitis that developed in the LysMCreIl10rafl/flRag1KO was not associated with increased intestinal Osm levels (online supplementary figure S7B), indicating that IL-10 signalling in macrophages is required for the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF independent of OSM.

gutjnl-2019-318264supp009.pdf (44.9KB, pdf)

We have previously shown that anti-TNF mAbs can skew monocytes to an M2-like CD206+ phenotype in vitro and in vivo in an FcγR-dependent manner.16 TNF is a trimeric cytokine that allows the formation of TNF-anti-TNF immune complexes that potently engage the FcγR in case of mAbs infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab but not with etanercept (a soluble receptor that binds a single trimer) or certolizumab (a single-arm Fab fragment).32 To the best of our knowledge, this is the only mechanism of action that is unique for mAbs and not shared with either certolizumab or etanercept, and the formation of such complexes may contribute to the relatively high rate of mucosal healing observed with anti-TNF mAbs.

As it has previously been shown that FcγR signalling can potently induce IL-10,19–21 we examined whether anti-TNF mAbs would induce IL-10 signalling in an FcγR-dependent manner. Our data showed that anti-TNF increased Il10 in an FcγR-dependent manner in mice both in vitro and in vivo. We find in all our in vitro experiments that expression of IL-10 is partially dependent on TNF. When we block TNF without FcγR engagement, with an anti-TNF Fab fragment, the level of IL-10 is reduced, while when we block TNF with a full IgG mAb, the expression of IL-10 is similar to isotype control IgG. When we engage the FcγR in the absence of TNF blockade using complexed IgG, the levels of IL-10 are increased to above the level of uncomplexed IgG control (figure 4; see also Bloemendaal et al 32). Together, this suggests that IL-10 expression is partially TNF dependent and that anti-TNF mAbs compensate for loss of IL-10 expression by engaging the FcγR, which subsequently results in downstream signalling via phosphorylation of STAT3.

Although our in vitro data suggest an autocrine IL-10 signalling loop, we did not establish the cell type responsible for increased intestinal IL-10 levels after anti-TNF mAb exposure in vivo.In situ hybridisation in anti-TNF treated mice suggests Il10 production by macrophages, but our data are not conclusive that the IL-10 is excessively produced by macrophages. Although the increase in Il10/Ifng and Il10/Il1b ratios could be an indirect reflection of the difference in level of inflammation between mice treated with anti-TNF and placebo, the fact that it is FcγR dependent again points towards the myeloid population. Despite the remaining uncertainty on the source of the IL-10, what is very clear from our data is that IL-10 sensing by macrophages is required for the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF mAbs. Consistent with the critical role of IL-10 signalling in regulatory macrophage skewing,12 13 blocking IL-10 signalling completely prevented anti-TNF-dependent regulatory macrophage skewing in both human cells in vitro and mice in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, the importance of IL-10 signalling may be relatively specific to the therapeutic effect of anti-TNF, we previously did not observe an effect on IL-10 by miltefosine, a drug that improved clinical signs as well as histology and potently inhibited multiple cytokines in the T-cell transfer model.33 Similarly, in a recent experiment with a small molecule kinase inhibitor, we observed almost complete mucosal healing without any effect on IL-10 expression in the same model (ME Wildenberg, personal communication 2019). In contrast, when we performed an unbiased drug screen for drugs that enhanced the anti-TNF-induced CD206+ regulatory macrophage polarisation, we identified albendazole as a drug that potentiates the effect of anti-TNF in vitro and in vivo.23 We found that albendazole specifically synergised with anti-TNF in upregulating IL-10 expression. Together, these data support the notion that upregulation of IL-10 may be relatively specific for the mode of action of anti-TNF mAbs. However, as the effect of the anti-IL-10Rα blocking antibody on the therapeutic efficacy of anti-TNF is not as impressive as the effect of the complete knock out of all FcγR,16 which may be because we fail to completely block IL-10R signalling using this approach, FcγR could also affect IL-10 signalling below the level of the receptor that is unaffected by the IL-10Rα block, or alternatively with mechanisms that are completely independent of IL-10 signalling. Various alternative mechanisms of action of anti-TNF have previously been described. One of the mechanisms described involves the binding of membrane-bound tumour necrosis factor (mTNF), which interferes with the antiapoptotic effect of monocyte expressed mTNF on CD4+ T cells, resulting in T-cell apoptosis.34 This mechanism is shared, however, between the anti-TNF mAbs and the Fab fragment certolizumab, and cannot explain the low rate of mucosal healing observed with certolizumab (4% at 10 weeks)35 compared with the mAbs infliximab (31% at week 10)36 and adalimumab (27% at week 12).37

Our data suggest that an inability of mucosal macrophages to respond to IL-10 signalling may be one of the mechanisms that underlies primary non-response to anti-TNF in patients with IBD. A recent study by Nunberg et al 38 showed that a subset of patients with CD have monocytes that display a reduced response to IL-10 when compared with healthy controls. A small study with PBMCs of patients with CD suggests that this response to IL-10 is associated with the response to TNF (not shown) and might be a very useful predictive marker for the response to anti-TNF therapy, which we aim to verify in a larger patient cohort. As this work focusses on the IL-10 dependent macrophage response for anti-TNF therapy in mouse models of chronic T-cell driven inflammation, this might only be relevant for patients with CD, as shown in figure 7. However, investigating the IL-10-dependent macrophage response in acute severe colitis might identify a similar response profile signature and could aid management decisions on rescue anti-TNF therapy versus surgery in this clinical situation, which is also subject of further investigation. The FcγR-mediated IL-10 effect on macrophage phenotype induced by anti-TNF mAbs may be less relevant in other immune-mediated diseases such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. As both patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis have more similar responses to different classes of TNF blockers, dependence on FcγR signalling seems relatively specific to patients with IBD. In conclusion, here we find that IL-10 signalling is required for anti-TNF-induced regulatory macrophage skewing in humans and mice. The therapeutic response to anti-TNF is completely dependent on IL-10 signalling in mucosal macrophages in a mouse model of colitis. Our data suggest that IL-10-dependent macrophage skewing to a CD206+ regulatory phenotype is a key aspect of therapy in IBD and that those patients in which a reduced response to IL-10 contributes to the aetiology of disease may respond less favourably to therapy with anti-TNF. This reduced response to IL-10 might be used to identify these patients, who may be better candidates to therapies with an alternative mode of action such as antibodies targeting IL-12/23 or IL-1β as recently suggested.39

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Dave Shealy (Janssen Research & Development) for the anti-mouse-tumour necrosis factor, anti-mouse-IL-12/23-p40 and isotype control monoclonal antibodies.

Footnotes

PJK and FMB contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published Online First. Affiliation 8 has been added.

Contributors: PJK, FMB, LW, MEW, EWMV and MvR performed experiments and analysed and discussed the data. AKG, ABvtW, GRAMD’H and GRvdB discussed the data. TLG and BL provided the LysMcreIl10rafl/flRag1KO mice and discussed the data. JSV provided FcgRKO/Rag1KO mice and discussed the data. HK, SV, AAtV and CYP provided patient samples and discussed the data. GRvdB and PJK supervised the study. PJK, FMB and GRvdB wrote the manuscript with input of all the authors.

Funding: This work was supported by a unrestricted research grant from the Janssen Prevention Center of Janssen Vaccines & Prevention BV, Leiden, the Netherlands, part of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, and by Health Holland, Top Sector Life Sciences and Health.

Competing interests: AKG and ABvtW are employees of Janssen Vaccines and Prevention B.V. GRvdB is currently an employee of Roche. CYP received research support from Takeda, speaker’s fees from Takeda, Abbvie and Dr. Falk Pharma, and consultancy fee from Takeda outside this work. Other authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam UMC(METC 2009_113) and the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital in Leuven (B322201213950/S53684) approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, et al. . Loss of response to Anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7:e135 10.1038/ctg.2015.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, van den Brink GR. Mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. ECCOJC 2016;10:989–97. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. . A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1586–93. 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleischmann R, Vencovsky J, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. . Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:805–11. 10.1136/ard.2008.099291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, et al. . Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:228–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa067594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S, et al. . Etanercept for active Crohn's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2001;121:1088–94. 10.1053/gast.2001.28674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. West NR, Hegazy AN, Owens BMJ, et al. . Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Med 2017;23:579–89. 10.1038/nm.4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franke A, Balschun T, Karlsen TH, et al. . Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility. Nat Genet 2008;40:1319–23. 10.1038/ng.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Franke A, McGovern DPB, Barrett JC, et al. . Genome-Wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 2010;42:1118–25. 10.1038/ng.717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kühn R, Löhler J, Rennick D, et al. . Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell 1993;75:263–74. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glocker E-O, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, et al. . Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2033–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zigmond E, Bernshtein B, Friedlander G, et al. . Macrophage-Restricted interleukin-10 receptor deficiency, but not IL-10 deficiency, causes severe spontaneous colitis. Immunity 2014;40:720–33. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shouval DS, Biswas A, Goettel JA, et al. . Interleukin-10 receptor signaling in innate immune cells regulates mucosal immune tolerance and anti-inflammatory macrophage function. Immunity 2014;40:706–19. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rennick DM, Fort MM, Davidson NJ. Studies with IL-10-/- mice: an overview. J Leukoc Biol 1997;61:389–96. 10.1002/jlb.61.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McRae BL, Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, et al. . Fc receptor-mediated effector function contributes to the therapeutic response of anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. ECCOJC 2016;10:69–76. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bloemendaal FM, Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, et al. . Anti-Tumor necrosis factor with a Glyco-Engineered Fc-Region has increased efficacy in mice with colitis. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1351–62. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vos ACW, Wildenberg ME, Duijvestein M, et al. . Anti-Tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies induce regulatory macrophages in an Fc region-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2011;140:221–30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vos ACW, Wildenberg ME, Arijs I, et al. . Regulatory macrophages induced by infliximab are involved in healing in vivo and in vitro. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:401–8. 10.1002/ibd.21818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerber JS, Mosser DM. Reversing lipopolysaccharide toxicity by ligating the macrophage Fc gamma receptors. J Immunol 2001;166:6861–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lucas M, Zhang X, Prasanna V, et al. . ERK activation following macrophage FcgammaR ligation leads to chromatin modifications at the IL-10 locus. J Immunol 2005;175:469–77. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gallo P, Gonçalves R, Mosser DM. The influence of IgG density and macrophage Fc (gamma) receptor cross-linking on phagocytosis and IL-10 production. Immunol Lett 2010;133:70–7. 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Read S, Powrie F. Induction of inflammatory bowel disease in immunodeficient mice by depletion of regulatory T cells. Curr Protoc Immunol 2001;Chapter 15 10.1002/0471142735.im1513s30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wildenberg ME, Levin AD, Ceroni A, et al. . Benzimidazoles promote anti-TNF mediated induction of regulatory macrophages and enhance therapeutic efficacy in a murine model. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1480–90. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koelink PJ, Wildenberg ME, Stitt LW, et al. . Development of reliable, valid and responsive scoring systems for endoscopy and histology in animal models for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:794–803. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donnelly RP, Dickensheets H, Finbloom DS. The interleukin-10 signal transduction pathway and regulation of gene expression in mononuclear phagocytes. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1999;19:563–73. 10.1089/107999099313695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li B, Gurung P, Malireddi RKS, et al. . Il-10 engages macrophages to shift Th17 cytokine dependency and pathogenicity during T-cell-mediated colitis. Nat Commun 2015;6:6131 10.1038/ncomms7131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kotlarz D, Beier R, Murugan D, et al. . Loss of interleukin-10 signaling and infantile inflammatory bowel disease: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Gastroenterology 2012;143:347–55. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kojouharoff G, Hans W, Obermeier F, et al. . Neutralization of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) but not of IL-1 reduces inflammation in chronic dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol 1997;107:353–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.291-ce1184.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noti M, Corazza N, Mueller C, et al. . TNF suppresses acute intestinal inflammation by inducing local glucocorticoid synthesis. J Exp Med 2010;207:1057–66. 10.1084/jem.20090849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hale LP, Greer PK. A novel murine model of inflammatory bowel disease and inflammation-associated colon cancer with ulcerative colitis-like features. PLoS One 2012;7:e41797 10.1371/journal.pone.0041797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dayer Schneider J, Seibold I, Saxer-Sekulic N, et al. . Lack of TNFR2 expression by CD4(+) T cells exacerbates experimental colitis. Eur J Immunol 2009;39:1743–53. 10.1002/eji.200839132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bloemendaal FM, Koelink PJ, van Schie KA, et al. . TNF-anti-TNF immune complexes inhibit IL-12/IL-23 secretion by inflammatory macrophages via an Fc-dependent mechanism. J Crohns Colitis 2018;10 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Verhaar AP, Wildenberg ME, te Velde AA, et al. . Miltefosine suppresses inflammation in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1–82. 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182917a2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atreya R, Zimmer M, Bartsch B, et al. . Antibodies against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induce T-cell apoptosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases via TNF receptor 2 and intestinal CD14⁺ macrophages. Gastroenterology 2011;141:2026–38. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hébuterne X, Lémann M, Bouhnik Y, et al. . Endoscopic improvement of mucosal lesions in patients with moderate to severe ileocolonic Crohn's disease following treatment with certolizumab pegol. Gut 2013;62:201–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rutgeerts P, Diamond RH, Bala M, et al. . Scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab is superior to episodic treatment for the healing of mucosal ulceration associated with Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:433–42. 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Sandborn WJ, et al. . Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn's disease: data from the extend trial. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1102–11. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nunberg MY, Werner L, Kopylov U, et al. . Impaired IL-10 receptor-mediated suppression in monocyte from patients with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:779–84. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shouval DS, Biswas A, Kang YH, et al. . Interleukin 1β mediates intestinal inflammation in mice and patients with interleukin 10 receptor deficiency. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1100–4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2019-318264supp001.pdf (158.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp002.pdf (55.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp003.pdf (78.1KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp004.pdf (54.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp005.pdf (48.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp006.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp007.pdf (31.5KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp008.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2019-318264supp009.pdf (44.9KB, pdf)