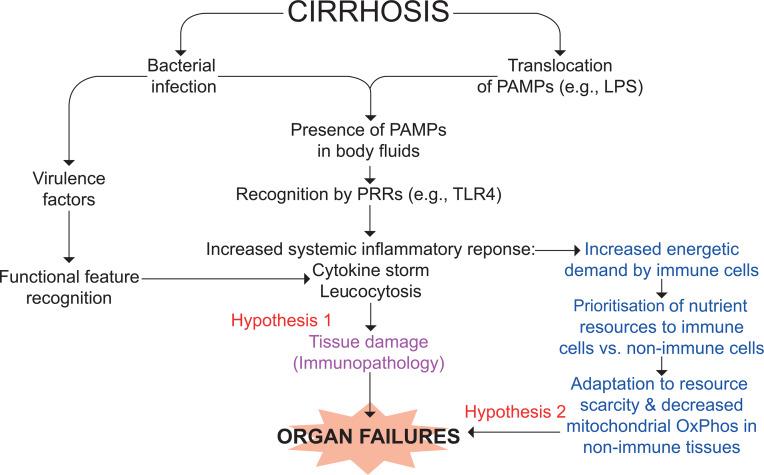

Figure 2.

Working hypothesis for the mechanisms of organ failures in ACLF. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS; eg, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)) are specifically recognised by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs; eg, Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 for LPS) expressed in innate immune cells and epithelial cells.4 7This process is called structural feature recognition. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs; eg, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), S100A8 (MRP8, calgranulin A) and S100A9 (MRP14, calgranulin B)), are molecules resulting from stressed cells that, once released, follow a similar path. PAMPs are either released by an infecting alive bacterium or ‘translocated’ from the gut lumen to blood, while DAMPs are released from tissues where necroptosis and pyroptosis take place (liver and extrahepatic organs (not shown)). Whichever the origin of these molecular patterns, their recognition by PRRs results in the production of a broad variety of inflammatory molecules (cytokines, chemokines and lipids), vasodilators and of reactive oxygen species, particularly in phagocytes. Intense systemic inflammation may cause collateral tissue damage (a process called immunopathology) and subsequently organ failures (hypothesis 1). Extrahepatic tissue damage can result in the release of DAMPs, which may perpetuate or accentuate PAMP-initiated and DAMP-initiated systemic inflammatory response (not shown).4 7 Systemic inflammation is energetically expensive, and the immune tissue can be prioritised for nutrient allocation at the expense of vital non-immune tissues. These may adapt to nutrient scarcity by reducing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and therefore ATP production, which would contribute to the development of organ failures (hypothesis 2). Of note, the two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.