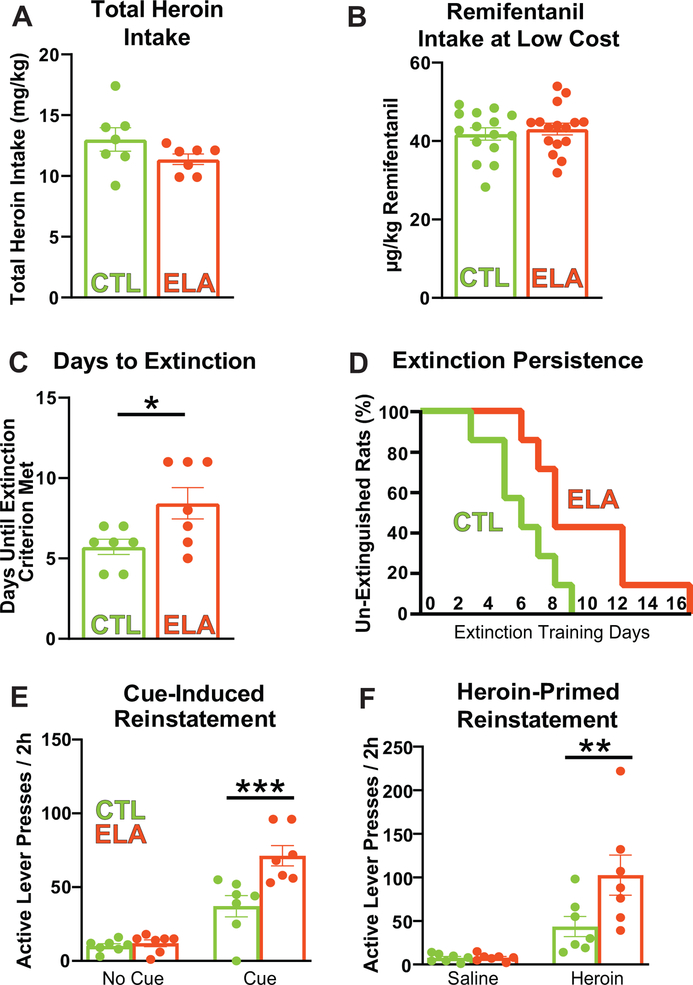

Figure 1: Early-Life Adversity Potentiates Heroin Seeking Behaviors:

(A) Total heroin self-administration did not differ between control and ELA rats (t12=1.550; P=0.1471), nor did (B) remifentanil self-administration at low effort (t29 = 0.5844; P = 0.5634). (C) Once response-contingent heroin was withdrawn, the ELA group resisted extinction more than controls (t12=2.509; P=0.0274). (D) Accordingly, the probability that ELA rats achieve extinction criterion (<20 active lever presses) each day was lower than in controls (Kaplan-Meier probability of survival; Log-rank curve comparison Chi square(df) = 4.491(1), P = 0.0341). (E,F) ELA augmented reinstatement of heroin-seeking by heroin-associated cues (main effect of cue/no cue: F(1,12) = 89.20; P<0.0001; main effect of rearing condition: F(1, 12) = 9.982; P = 0.0082; cue × ELA interaction: F(1,12) = 12.49; P = 0.0041. Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests CTL vs ELA: no cue: t24 = 0.2543; P > 0.9999; cue: t24 = 4.676; P = 0.0002), and by a heroin priming injection (main effect of heroin/saline prime: F(1,12) = 27.00; P = 0.0002; main effect of rearing condition: F(1, 12) = 4.891; P = 0.0471; prime × ELA interaction: F(1,12) = 5.447; P = 0.0378. Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests CTL vs ELA: saline prime: t24 = 0.01554; P > 0.9999; heroin prime: t24 = 3.210; P = 0.0075). Circles within each bar represent individual animals in CTL (green) and ELA (orange) groups. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.