Highlights

-

•

Practical, evidence-informed advice considers the spectrum of public health science.

-

•

This framework fills a gap in the comprehensive development of vaccine guidance.

-

•

It enables the systematic examination of ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability.

-

•

In Canada, successful implementation has led to timely, transparent recommendations.

-

•

These tools, based on extensive research, can be used by advisory groups worldwide.

Keywords: Vaccine Program, Ethics, Equity, Feasibility, Acceptability, Framework

Abbreviations: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States; ACS, Advisory Committee Statement; CCDPHE, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity; CIC, Canadian Immunization Committee; CIG, Canadian Immunization Guide; EEFA, Ethics, Equity, Feasibility, Acceptability; EtD, Evidence to Decision; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HZ, Herpes Zoster; LZV, Live Zoster Vaccine; NACI, National Advisory Committee on Immunization; NITAG, National Immunization Technical Advisory Group; PHAC, Public Health Agency of Canada; PHECG, Public Health Ethics Consultative Group; PHN, Post-Herpetic Neuralgia; PROGRESS, Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex; Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital; P2ROGRESS And Other Factors, Pre-existing condition, Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language/immigrant/refugee status, Occupation, Gender identity/sex, Religion/belief system, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital, Age and Other factors (e.g. risk behaviours); RZV, Recombinant Zoster Vaccine; SAGE, Strategic Advisory Group of Experts; VPD, Vaccine-Preventable Disease; WHO, World Health Organization

Abstract

For the successful implementation of population-level recommendations, it is critical to consider the full spectrum of public health science, including clinical and programmatic factors. Current frameworks may identify various factors that should be examined when making evidence-informed vaccine-related recommendations. However, while most immunization guidelines systematically assess clinical factors, such as efficacy and safety of vaccines, there is no published framework outlining how to systematically assess programmatic factors, such as the ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability of recommendations. We have addressed this gap with the development of the EEFA (Ethics, Equity Feasibility, Acceptability) Framework, supported by evidence-informed tools, including Ethics Integrated Filters, Equity Matrix, Feasibility Matrix, and an Acceptability Matrix. The Framework and tools are based on five years of environmental scans, systematic reviews and surveys, and refined by expert and stakeholder consultations and feedback. For each programmatic factor, the EEFA Framework summarizes the minimum threshold for consideration and when further in-depth analysis may be required, which aspects of the factor should be considered, how to assess the factor using the supporting evidence-informed tools, and who should be consulted to complete the assessment. Research, particularly in the fields of vaccine acceptability and equity, has validated the utility and comprehensiveness of the tools. The Framework has been successfully used in Canada for clear, timely, transparent vaccine guidance with positive stakeholder feedback on its comprehensiveness, relevance and appropriateness. Applying the EEFA Framework allows for the systematic consideration of the spectrum of public health science without a delay in recommendations, complementing existing decision-making frameworks. This Framework will therefore be useful for advisory groups worldwide to integrate critical factors that could impact the successful and timely implementation of comprehensive, transparent recommendations, and will further the global objective of developing practical and evidence-informed immunization policies.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) global strategic objective of strengthening national capacity to formulate immunization policies through better use of evidence is being realized in Canada through the expanded mandate of its national immunization technical advisory group (NITAG) [1]. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) is an expert advisory group to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and provides medical, scientific, and public health advice on the use of vaccines. National immunization recommendations in Canada reflect upon Erickson and colleagues’ “Analytic Framework for Immunization Recommendations in Canada” (Analytic Framework) [2]. This framework outlines a number of traditional scientific (e.g. disease burden, vaccine characteristics) and programmatic (e.g. feasibility, acceptability, ethics, cost) factors that are typically considered important by decision-makers when evaluating immunization programs. The significance of these programmatic factors, such as vaccine acceptability, is increasingly acknowledged by NITAGs and decision-makers around the world in an era where vaccine hesitancy is emerging as a threat to global health [3]. We have developed an EEFA (Ethics, Equity, Feasibility, Acceptability) Framework with supporting evidence-informed tools for each EEFA factor to help decision-makers systematically assess critical programmatic issues, thereby strengthening capacity for comprehensive, evidence-informed immunization program recommendations.

Since its establishment in 1964, NACI has based its guidance primarily on the traditional scientific factors outlined in Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2], through the structure and processes described in detail in a previously published paper [4]. Until recently, the Canadian Immunization Committee (CIC), a federal/provincial/territorial committee, produced separate recommendations [5], [6], [7] that built upon NACI’s work by including the consideration of programmatic factors within Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2]. However, this two-step process inevitably resulted in extended timelines between vaccine authorizations to program guidance, contributing to variable program implementation across Canada.

In an effort to improve efficiencies, effectiveness and best practice of immunization recommendations in Canada, NACI’s mandate officially expanded in 2019 to include the systematic consideration of programmatic factors (i.e. ethics, equity, feasibility, acceptability, and economics) in addition to traditional scientific factors (i.e. burden of disease and vaccine characteristics). Factors in Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2] more appropriately assessed at the local level (e.g. political considerations) continue to be excluded from the mandate of the national committee. Though NACI has reflected upon aspects of programmatic issues to varying degrees during deliberations in the past, these discussions have not been conducted in a systematic, comprehensive or transparent manner and were not an explicit component of NACI’s mandate until now. While the process for knowledge synthesis, retrieval, and translation into recommendations informed by critically appraised clinical evidence is clearly documented and followed by NACI [8], a similarly transparent and analytic methodology does not exist for non-clinical evidence.

Internationally, there have been dozens of published frameworks used to inform vaccine decisions over the years; almost all include explicit discussion of disease burden and vaccine characteristics, and most of these frameworks have included explicit consideration of programmatic factors [9]. Notably, many NITAGs are now framing vaccine decisions using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology and Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework, which has also recently added criteria for consideration of feasibility, acceptability, cost, and equity [10]. The WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) and Immunization in Practices Advisory Committee have been integrating programmatic considerations for many years, and the WHO’s Programmatic Suitability for (vaccine) Pre-Qualification screening process assesses and improves the programmatic suitability of prospective vaccines for developing country public-sector immunization programs through the application of suitability criteria [11]. However, little support exists to direct how these criteria can be reviewed systematically and informed by evidence within a vaccine guideline. The rigor of data collection, analysis and reporting of the different types of evidence associated with programmatic factors, and relative importance of these issues compared to more traditional factors influencing vaccine recommendations, has yet to be adequately explored [9]. Furthermore, the ascertainment of how and why such factors may vary between settings and vaccines is needed. Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2] outlines key questions for consideration for ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability (summarized in Table 1 [16]); however, no frameworks currently exist to guide the answers to these questions.

Table 1.

Key questions about and definitions for programmatic factors.

|

Our EEFA Framework addresses these gaps and provides evidence-informed tools to facilitate systematic consideration of programmatic factors in guidance development and answer the questions posed by Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2]. While cost-effectiveness is an often cited programmatic factor, due to the distinctiveness of economic considerations, a separate process under an economics task group to determine a standardized approach to this factor is ongoing. Therefore, the consideration of economics is not included in the EEFA Framework.

The EEFA Framework is based on extensive research and reviews of the evidence on issues that are important to consider with respect to ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability in relation to vaccination. The evidence-informed supporting tools that comprise the EEFA Framework facilitate the systematic assessment of each programmatic factor, preventing the need to conduct separate, time-consuming evidence reviews for each immunization recommendation. The implementation of the Framework will facilitate the development of timely, comprehensive, and appropriate guidance for immunization programs. The objectives of advisory bodies like those at the WHO serve to facilitate the decision-making process that NITAGs employ when advising their respective jurisdictions, and improve prospective vaccines for public sector programs through clearly outlined suitability criteria. As no other such tool exists, this Framework will be useful for advisory bodies globally, including NITAGs who seek to systematically assess programmatic factors that could impact the successful implementation of vaccine recommendations, guide the development of prospective vaccines for viable inclusion in immunization programs, and support the global objective of evidence-informed immunization policies.

2. Methods

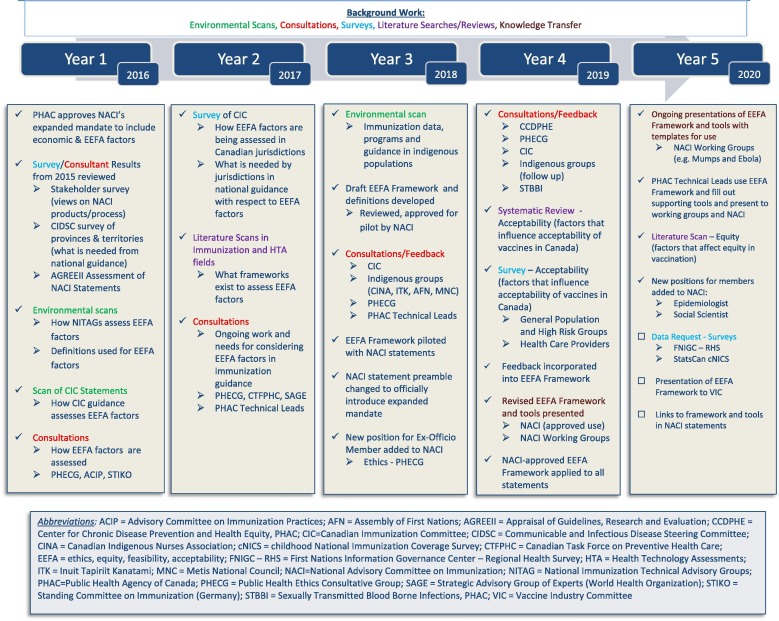

As depicted in Fig. 1 , extensive work has been conducted over five years to develop, test, improve, and implement the EEFA Framework and supporting tools.

Fig. 1.

Background work leading to the development and implementation of the EEFA framework.

We adopted definitions of the terms “ethics”, “equity”, “feasibility” and “acceptability” for the application of the EEFA Framework (summarized in Table 1), informed by Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2] and an environmental scan of the literature.

To explore what is currently being done and what is needed to incorporate EEFA considerations in immunization guidance, and to inform the development of evidence-informed tools to support the expansion of NACI’s mandate, we conducted and commissioned a number of environmental scans and literature reviews, as well as surveys of and consultations with experts and stakeholder groups. PHAC Technical Leads, who, alongside the respective NACI Working Group Chairs, lead the development of NACI guidance, were integrally involved throughout the process. NACI’s Evidence-Based Methodology Working Group (composed of current and past NACI members as well as external experts) provided input at various stages of development. NACI members representing various fields of expertise and stakeholder groups (Table 2 ) were consulted, provided feedback, and approved the use of the EEFA Framework and supporting tools. NACI’s membership was recently expanded along with its mandate to include enhanced expertise in epidemiology, ethics, and social sciences.

Table 2.

Membership on the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI).

|

In advance of the decision to expand NACI’s mandate, we conducted an online national stakeholder survey to explore existing views on NACI’s process to develop evidence-informed recommendations, and its products [including Advisory Committee Statements (ACSs) and the Canadian Immunization Guide (CIG)] which summarize this guidance (Unpublished results). Six hundred and fifty-six stakeholders, including members of national immunization committees and Canadian provincial and territorial advisory groups, as well as frontline users of NACI guidance who vaccinate or counsel about vaccination (e.g. physicians, nurses, pharmacists), responded to the survey. In the same year, we commissioned an external assessment of the quality and reporting of NACI ACSs using the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation) international tool [12]. These baseline investigations revealed that the timeliness, clarity, and transparency of NACI recommendations summarized in ACSs and the CIG are critical principles to be upheld through the expansion of NACI’s mandate.

To more specifically investigate how jurisdictions within Canada assess ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability, as well as what they require from NACI with respect to the assessment of these factors when making immunization decisions, we surveyed provincial and territorial representatives of CIC in 2017 (Unpublished results). The survey identified a lack of consistency and an expressed need for tools to systematically review and summarize the evidence on how these factors impact immunization recommendations. The importance of timeliness, transparency, and clarity of NACI recommendations was a recurring theme in this survey. As in a previous survey conducted by the Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee of the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network in 2015 (Unpublished results), jurisdictions also requested that available evidence on various factors be summarized with options for management presented in national guidance.

Between 2016 and 2018, we conducted literature scans in the immunization and health technology assessment fields, environmental scans of resources from key international NITAGs 1 and jurisdictions within Canada, and reviews of CIC immunization guidance documents to ascertain the incorporation of EEFA considerations. Through this initial work, we became aware of ongoing initiatives in this area and scheduled interviews with key informants from organizations within Canada (e.g. Public Health Ethics Consultative Group - PHECG, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care) and outside (e.g. ACIP, SAGE, STIKO) to learn more. Overall, we discovered a great deal of variability in how issues related to ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability were examined and whether they were considered systematically at all. When any of these factors were comprehensively considered with de novo frameworks, timeliness of guidance could reportedly be delayed up to two years. While frameworks exist in different fields to assess issues related to one specific factor, and many NITAGs are using tables summarizing evidence that include mention of ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability when making recommendations, a comprehensive tool to systematically address these factors as they relate to immunization in a timely way that didn’t delay guidance was missing.

Informed by this background work, we drafted the EEFA Framework and a supporting evidence-informed tool for each factor (Ethics Integrated Filter, Equity Matrix, Feasibility Matrix, Acceptability Matrix) in 2018. Through an iterative process, we refined the tools based on written and verbal feedback from a range of stakeholder groups and experts in ethics (e.g. PHECG), equity (e.g. Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity), feasibility (e.g. provincial and territorial representatives who implement recommendations), and acceptability (e.g. international expert in vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Ève Dubé), as outlined in Fig. 1. We also sought specific feedback from representatives of specific target or high risk groups (e.g. Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association). To ensure our Framework is applicable and relevant to Indigenous peoples in Canada, we conducted an environmental scan of existing data, programs and guidance for this population.

To validate the applicability, utility and comprehensiveness of our Acceptability and Equity Matrices, and to pre-populate them as much as possible for vaccination in general and for specific vaccines, we conducted additional research in these areas. Data from existing and future cycles of surveys such as the First Nations Regional Health Survey (identified through our environmental scan) which assesses immunization coverage and attitudes of First Nations people living on reserve and in northern communities, and the childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey (cNICS), will add to the evidence summarized in these EEFA tools over time.

We commissioned researchers at the Alberta Research Center for Health Evidence (ARCHE) to conduct a systematic review on the factors influencing acceptability of vaccines among the general public, healthcare providers and policymakers in Canada over the past 5 years [13]. To address gaps in the literature, we also contracted public opinion research of Canadians and their healthcare providers [14]. Together, this research examined whether the Acceptability Matrix accurately captures the factors affecting acceptability of vaccination from the perspectives of the general public, specific high risk or target groups, healthcare providers, and policymakers. In 2019, we commissioned the researchers at ARCHE to synthesize the evidence on the factors contributing to health inequities related to vaccination in Canada and similar high-income countries with universal (or near-universal) healthcare systems over the past twenty years (Unpublished results). The evidence was summarized into our Equity Matrix for specific vaccines and vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs), and the utility of the matrix was assessed. The research into acceptability and equity validated that the matrices developed were comprehensive, useful tools, requiring only minor changes in terms of broadening the examples provided for some of the categories in the matrices.

In 2018, NACI approved the prospective piloting of the EEFA Framework to systematically summarize issues related to ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability for consideration during deliberations on recommendations, starting with the Updated Recommendations on the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines [15].

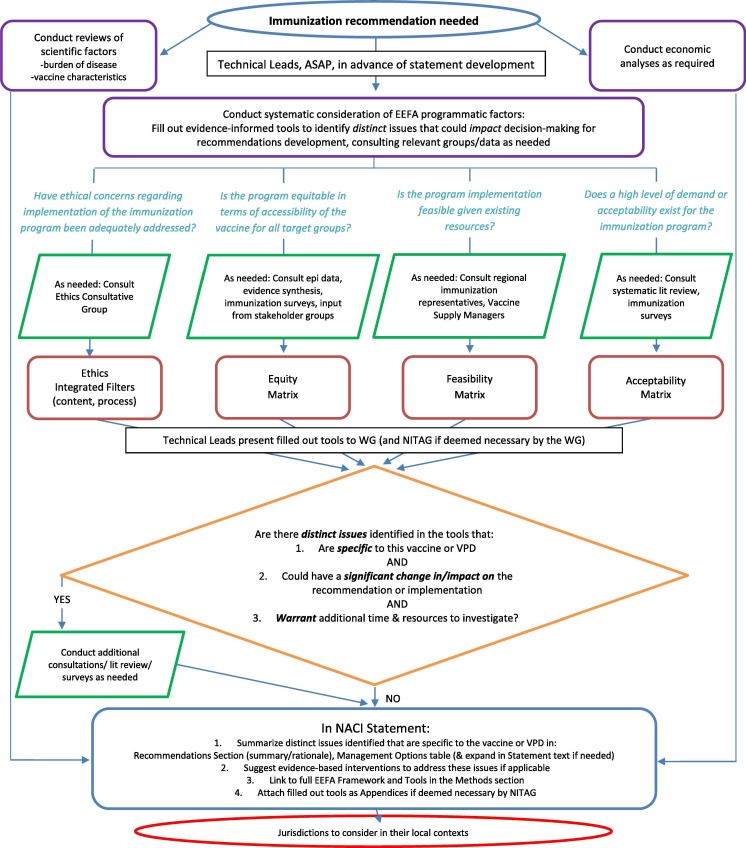

Over the course of two years, the Framework has been evaluated based on feedback from NACI Technical Leads filling out the tools, NACI working group and committee members deliberating on the information presented in the tools to make immunization recommendations, and various other stakeholder groups (e.g. CIC) receiving and implementing NACI guidance using the EEFA Framework, as outlined in Fig. 1. The EEFA Framework and supporting tools were noted to be: “comprehensive”, “relevant”, “sensible” and “met the needs”, however there were concerns about the impact on timeliness and resources to implement the Framework, and some confusion about how it would be used. As a result, we developed an algorithm outlining the process for applying the EEFA Framework (Fig. 2 ) to demonstrate that the extensive background work leading up to the development and refining of the Framework and supporting tools would reduce the time and resources needed to apply them, as separate evidence reviews would rarely be required. The NACI Technical Leads acknowledged that this was, indeed, the case as they were typically able to apply the Framework to guidance within a few days. As of the fall of 2019, the revised EEFA Framework has been approved by NACI for implementation in the development of immunization guidance, and knowledge translation of its use continues. It has been successfully applied in six NACI ACSs to date [15], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], with more underway.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm outlining the process for applying the EEFA framework.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall EEFA Framework (Table 3)

Table 3.

Overall EEFA framework.

|

The purpose of the EEFA Framework is to provide evidence-informed tools for the systematic consideration of programmatic factors in order to develop clear, comprehensive recommendations for timely, transparent decision-making, thereby upholding the principles identified by stakeholders in our background work as critical for NACI guidance.

The following supporting evidence-informed tools (described below) have been developed for application of the EEFA Framework:

Table 4.

Core Ethical Dimensions Filter: To ensure guidance upholds and integrates core ethical dimensions for public health.

|

a Societal support to minimize disproportionate risks taken by individuals in their duty to protect the public.

b Steps from PHECG Framework: 1) identify the issue and context, 2) identify ethical considerations, 3) identify and assess options, 4) select best course of action and implement, 5) evaluate.

Table 5.

Ethical Procedural Considerations Filter: To ensure guidance processes uphold and integrate ethical procedural considerations.

|

Table 6.

Equity Matrix with Examples (across different VPDs): To identify potential, distinct inequities that may arise with the recommendation, reasons for inequities, and interventions to reduce the inequity and improve access.

|

Table 7.

Feasibility Matrix with Examples (for potential SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Vaccine): To identify potential, distinct issues with respect to the vaccine and immunization program to address the feasibility of implementing the recommendation.

|

Table 8.

Acceptability Matrix with Examples (across different VPDs): To identify potential distinct issues with the acceptability of a recommendation from the perspective of the public, providers, and policymakers.

|

As outlined in Table 3 , the EEFA Framework summarizes the minimum threshold for consideration of each programmatic factor and when further in-depth analysis may be required, which aspects of the factor should be considered, how to assess the factor using evidence-informed tools, and who should be consulted to assist in the assessment.

Fig. 2 demonstrates how the EEFA Framework is applied in the context of the full spectrum of public health science and best practice, including traditional scientific as well as economic factors, when developing immunization recommendations. As soon as the need for immunization recommendations is identified, the Technical Leads use the evidence-informed tools to systematically consider issues related to ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability and answer the specific questions from Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2]. The algorithm directs the Technical Leads to previously conducted key consultations, reviews and research to refer to when filling out the tools with evidence. Additional consultations and research will only be required in circumstances when distinct issues that have not been captured in the background work are identified in the tools that: (1) are specific to the vaccine or vaccine preventable disease (VPD), and (2) could have a significant change in/impact on the recommendation or its implementations, and (3) warrant additional time and resources to investigate. Technical leads present the completed tools to the relevant NACI Working Group as part of the full evidence base considered when developing recommendations.

As outlined in the algorithm, once knowledge synthesis, retrieval and deliberation on the traditional scientific, economic, and EEFA factors of a recommendation is complete, it is summarized in the NACI ACS. Only EEFA issues unique to a particular vaccine recommendation that may impact decision-making or implementation will be summarized in the context of other traditional scientific and economic considerations. Evidence-informed interventions to address these issues may be suggested if applicable. Recognizing that there are operational and epidemiological differences across the country, and in response to jurisdictional requests that available evidence on these factors be summarized with options for management presented in national guidance, NACI developed a “Management Options Table” (see Table 9 for an example [19], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]).

Table 9.

Example of NACI’s management options table comparing herpes zoster vaccines. (See below-mentioned references for further information.)

|

Abbreviations: AS = Adjuvant System, HZ = Herpes Zoster, LZV = Live Zoster Vaccine, PHN = Post-Herpetic Neuralgia, RZV = Recombinant Zoster Vaccine, SAE = Serious Adverse Events, VE = Vaccine Efficacy.

The Management Options Table outlines options for implementation of a vaccine recommendation (e.g. in terms of different vaccine products, vaccination schedules, or target groups), summarizes key evidence available on the array of scientific and programmatic factors considered, as well as key decision points for stakeholders to examine when evaluating the options. In this way, the conclusions of the EEFA Framework will be presented transparently within the spectrum of public health science for consideration by the jurisdictions in their own contexts, similar to a GRADE EtD table [10]. Links to the full EEFA Framework and supporting tools, as well as completed tools for the particular vaccine recommendations (if deemed necessary), will be attached to the NACI ACS. Following this process allows for timely, transparent, clear, comprehensive recommendation development.

4. Ethics integrated filters

In 2017, the Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG) and its Secretariat developed a “Framework for the Ethical Deliberation and Decision-Making in Public Health: A Tool for Public Health Practitioners, Policy Makers and Decision-Makers”, which “guide(s)…the analysis of the ethics implications of proposed public health programs, policies, interventions and other initiatives … [and] help(s) users clarify issues, weigh relevant considerations, and identify possible options” [31, p1]. The Framework was intended to be applicable to “the range of public health activities in which PHAC is involved, including the development and implementation of public health programs, policies, interventions and other initiatives.” The PHECG framework is divided into: (1) Core ethical dimensions in public health, and (2) Procedural considerations [31]. NACI’s Ethics Integrated Filter is based on the PHECG Framework, and is likewise divided into two components related to: (1) content of NACI recommendations, and (2) NACI procedural considerations. Together, these filters facilitate the assessment of recommendation content development procedures in order to answer the relevant question on ethics in Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework: “Have ethical concerns regarding implementation of the immunization program been adequately addressed?” [2]

In reviewing NACI’s plan for the expanded mandate, PHECG advised that “ethics considerations are akin to filters that are applied at each step of decision-making, rather than a separate topic of discussion to be assigned a specific weight or raised after the fact as part of an oversight function…ethics considerations relate to the process of deliberation as well as to their content” (Unpublished results). The ethics filters that accompany the EEFA Framework are designed to ensure that the core ethical dimensions have been considered and integrated into the content of NACI recommendations (using the Core Ethical Dimensions Filter, Table 4), and that NACI processes integrate and uphold ethical procedural considerations (using the Ethical Procedural Considerations Filter, Table 5), as outlined in the PHECG Framework [31]. The filters outline questions to ensure each ethical dimension for NACI recommendations and procedural consideration for NACI processes has been reflected upon, and potential issues have been further analyzed through a legitimate process with options presented. Questions from Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2] related to equity, feasibility, and acceptability are included in the Core Ethical Dimensions Filter. The final column of the filters provides tools to assist with integrating each ethical principle. For instance, the Management Options Table (example provided by Table 9) clearly summarizes the evidence and outlines risks and benefits of recommendation options to ensure the ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence have been considered. NACI guidance is web-posted and distributed to stakeholders to uphold the core ethical dimension of respect for persons and communities with the right to exercise informed choice based on all available evidence. Ethical considerations are integrated throughout the NACI process and recommendation development, including the assessment of equity, feasibility, and acceptability.

If, after applying the Core Ethical Dimensions Filter, a distinct ethical dilemma arises for a specific recommendation, further scenario-based ethical analysis may be required using the steps outlined in the PHECG Framework [31]: (1) identify the issue and context, (2) identify ethical considerations, (3) identify and assess options, (4) select best course of action and implement, (5) evaluate.

NACI’s Interim Statement on the Use of the rVSV-ZEBOV Vaccine for the Prevention of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) [19] provides an applied example of the Core Ethical Dimensions Filter. When assessing the dimension of beneficence and non-maleficence, the EVD Working Group considered whether the benefit of deferring all other vaccinations when the live rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine is administered as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) outweighed the risks. An in-depth scenario-based ethics analysis using the steps described above was conducted. Ultimately, due to the life-threatening disease risks of EVD (contributing to a high level of demand and acceptability for the vaccine), the unknown potential for vaccine interactions and the potential to mimic symptoms of EVD, as well as the ability to vaccinate with deferred vaccines at a later time, the committee selected the option of deferring other vaccinations as the best course of action. The key considerations in the ethical analysis were transparently summarized in the Recommendations section of the guidance: “When used as PEP against ZEBOV, NACI recommends that the pre-market rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine should not be given simultaneously with other live or inactivated vaccines due to the potential for immune interference and the need to be able to monitor for potential symptoms of EVD and rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine adverse events without potential confounding from other vaccine adverse events…Considering the ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence, delaying any other vaccines to prioritize the pre-market rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine for individuals who have had an exposure to ZEBOV is…ethically justifiable” [19].

The Ethical Procedural Considerations Filter (Table 5) guides overall NACI processes. Procedures have been developed (e.g. Conflict of Interest Guidelines) to ensure that the ethical principles of accountability, inclusiveness, responsibility, responsiveness, and transparency are upheld. For example, every ACS follows a statement template to ensure that the process followed and evidence used to inform a recommendation (including certainty of evidence and unknowns), and the rationale (including the systematic assessment of all scientific and programmatic factors) is summarized for each immunization recommendation. These processes ensure the transparency of NACI recommendations.

Ethical and equity analyses will be particularly relevant and necessary to rationalize off-label vaccine recommendations. While most NITAGs provide off-label recommendations for vaccines [32], there is an understanding that these are most often issued when driven by an equity or ethical principle necessitating their use outside of regulatory indications as per product monographs [33]. Together, the Core Ethical Dimensions and Procedural Considerations Filters, applied throughout recommendation development, provide a systematic process to clarify, prioritize, and justify possible courses of action based on ethical principles for complex issues.

5. Equity Matrix

The Equity Matrix (Table 6) was informed by the PROGRESS-Plus model of health determinants and outcomes initially introduced by Evans and Brown in 2003 [34], and endorsed by the Cochrane Equity Methods Group for equity-focused systematic reviews [35], [36]. Factors that may be associated with possible health inequities considered by NACI include expanded categories of those captured in PROGRESS-Plus: place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language/immigrant or refugee status, occupation, gender identity/sex, religion/belief system, education/literacy level, socioeconomic status, and social capital. To ensure important vaccine-specific equity factors not explicitly highlighted in the PROGRESS-Plus model are examined, our Equity Matrix also includes pre-existing condition, age, and other factors such as risk behaviours (e.g. smoking, drug and alcohol use disorders). Thus, the factors in our Equity Matrix are defined by the acronym: P2ROGRESS And Other Factors.

The second column of the matrix outlines reasons why the inequity may exist, including differential access to the vaccine, or, as outlined in the Quinn and Kumar framework [37], pathways through which the social determinants of health can influence the differential exposure, susceptibility and disease severity, and consequences of infectious diseases. Within the PHECG Framework, the principle of justice is a core ethical dimension to consider for public health interventions [31]. Within NACI’s Core Ethical Dimensions Filter, the Equity Matrix is used to ensure the principle of justice is addressed by answering the following questions from Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework: “Is the recommendation equitable in terms of accessibility of the vaccine for all target groups? Are there special considerations for vulnerability of those most at risk?” [2].

The first column in the matrix summarizes factors that may contribute to health inequity to allow for identification of vulnerable groups most at risk, for whom reduced access to the vaccine being recommended may further potentiate the inequity. For each group identified, the primary source(s) of the inequity will be identified if possible (second column) to aid in the process of reviewing special considerations for vulnerability or evidence-based interventions that could address the inequity and improve access (third column). Table 6 illustrates the utility of the Equity Matrix in identifying potential inequities, reasons for inequities, and interventions to reduce the inequities with examples across different VPDs.

The ARCHE researchers who conducted the evidence synthesis on factors contributing to health inequities related to vaccination (Unpublished results) found a vast body of research with pre-existing disease, age and gender identity or sex being the most commonly reported. This review validated that the Equity Matrix is “a useful framework for identifying and categorizing factors that may contribute to inequities related to vaccination.” The Equity Matrix was used to summarize the literature for vaccination in general and for specific vaccines. These pre-populated matrices will reduce the need for full evidence reviews with every ACS and improve timeliness. As issues specific to a particular vaccine arise, epidemiological data and input from stakeholder groups and organizations may be sought.

Some inequities specific to particular guidance will be addressed in other sections throughout a NACI ACS (e.g. the Epidemiology section identifies groups at high risk of disease or complications; a recommendation may include specific target groups due to inequity from increased disease exposure, susceptibility, severity or complications). However, some factors contributing to the inequity may be more systemic (e.g. remote communities, low socioeconomic status). Suggestions may be made within a NACI recommendation to increase access to immunization to address inequities (e.g. gender-neutral school-based programs and mobile clinics, publicly funded vaccine).

The Equity Matrix enabled NACI to systematically and transparently work through the spectrum of public health considerations to reduce the inequity and improve access in its Updated Recommendations on the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines [15]. The Management Options Table (see Table 9) summarizes these considerations in the context of other factors. Age is the predominant risk factor for the development of herpes zoster (HZ) and post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). After reviewing the evidence, NACI identified that “the higher efficacy of the recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) vaccine in adults 50 years of age and older, with minimal waning of protection, and factoring in cost-effectiveness of the immunization, all supported a public health program level recommendation to vaccinate populations ≥ 50 years of age. This population is at higher risk of HZ and PHN and will likely continue to be protected with RZV at older ages as the risk of HZ and PHN continues to increase.” Age was identified as a factor contributing to health inequity due to differential disease susceptibility, and a publicly funded immunization program was recommended as an intervention to reduce the inequity and improve access.

In addition to age, immunocompromise as a pre-existing condition was identified by NACI as a factor contributing to health inequity due to differential disease susceptibility, severity or consequences. In its ACS, NACI asserts, “Individuals who are immunocompromised, either due to underlying conditions or immunosuppressive agents, have an increased risk of developing HZ and may be more likely to experience atypical and/or more severe disease and complications.” NACI considered this inequity in the context of limited peer-reviewed, published data specifically supporting the use of RZV in immunocompromised populations, as well as the fact that immunocompromise is not a contraindication for the use of RZV, and made a discretionary recommendation that the use of RZV be considered for immunocompromised adults 50 years of age or older. NACI weighed equity considerations against insufficient data on efficacy in this population and felt that the benefits of considering vaccination with RZV in a population with differential disease susceptibility and severity/consequences outweighed the risks.

6. Feasibility Matrix

The Feasibility Matrix was informed by components listed in Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2], survey responses and tools shared by provinces and territories, and expert input as depicted in Fig. 1. The matrix outlines factors related to the vaccine and immunization program that may affect the feasibility of implementing a recommendation. These include issues related to resource availability (e.g. vaccine supply, human resources for program implementation) and integration with existing programs (e.g. vaccine coverage in a particular target group, alignment with existing immunization schedules). Table 7 demonstrates how the Feasibility Matrix can help identify potential issues with the feasibility of implementing a prospective SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 vaccine program. Within the PHECG Framework, the principle of distributive justice (i.e. related to the fair deployment of resources) is included as a core ethical dimension (under justice) to consider for public health interventions [31]. Within NACI’s Core Ethical Dimensions Filter, the Feasibility Matrix is used to ensure the principle of distributive justice is addressed by answering the following question from Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework, “Is implementation feasible given existing resources?” [2].

The Technical Lead, with input from the relevant Working Group and consultation with the CIC and Vaccine Supply experts within PHAC, reviews the matrix to identify potential issues that may arise with respect to feasibility of implementation of a recommendation. For example, NACI’s Updated Recommendations on the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines [15] considered the relative feasibility of RZV vaccination which requires 2 doses compared to the Live Zoster Vaccine (LZV) which only requires a single dose. The committee recognized that more resources would be required for administration of an additional dose with RZV. However, given other scientific and programmatic considerations (i.e. higher efficacy, lower waning of protection and better cost-effectiveness of RZV), NACI recommended RZV vaccine. The committee recognized issues with feasibly implementing a new publicly funded two-dose vaccination program for all adults 50 years of age and older given operational constraints and resource requirements. To enable the judicious use of resources, the committee provided options for prioritization of targeted immunization programs based on the relative merits of vaccinating different age cohorts (with respect to epidemiology, equity and cost-effectiveness). Furthermore, an alternative vaccination schedule (0, 12 months versus 0, 2–6 months) was suggested for public health programs to align with existing immunization schedules and improve coverage of the second dose by simultaneous administration with other adult vaccines (e.g. seasonal influenza). This recommendation was based on a study demonstrating an acceptable safety profile and robust anti-gE immune response [30]. These considerations were transparently outlined in the Management Options Table (see Table 9) in the context of other factors.

7. Acceptability Matrix

Our Acceptability Matrix summarizes the many factors that can influence the acceptability of a vaccine into four categories:

-

1.

Perceptions of the vaccine (e.g. safety concerns, vaccine efficacy)

-

2.

Perceptions of the disease being vaccinated against (e.g. severity of disease, outbreak, groups at risk, personal risk)

-

3.

The process of getting vaccinated (e.g. access to the vaccine, opportunity cost to get the vaccine)

-

4.

Individual/Personal factors (e.g. beliefs and values, experiences, trust in healthcare providers and the healthcare system, trust in vaccine experts and vaccine industry, social norms/pressures and media)

These factors will be considered from the perspective of:

-

1.

The public (general public and target/high risk groups)

-

2.

Healthcare providers

-

3.

Policymakers

Public perspective is divided into the general public and target/high risk groups. Target groups are the population for whom the vaccine is recommended, while high risk groups are populations who have been empirically identified as a group at elevated risk for burden of disease or low immunization coverage. Healthcare providers are those who administer or provide advice on vaccines (e.g. family physicians, nurses, pharmacists, pediatricians, midwives, obstetricians and gynaecologists). Policymakers are those who make decisions on the implementation of an immunization recommendation within a jurisdiction.

In the PHECG Framework, the principle of respect for persons and communities (i.e. right to exercise informed choice based on all available evidence) is a core ethical dimension to consider for public health interventions [31]. Within NACI’s Core Ethical Dimensions Filter, the Acceptability Matrix is used to ensure the principle of respect for persons and communities is addressed by answering the following question from Erickson et al.’s Analytic Framework [2], “Does a high level of demand or acceptability exist for the immunization program?”

The systematic review of acceptability literature in Canada commissioned during the development of the EEFA Framework identified over 100 factors linked to vaccine acceptability (some common across vaccines and others that are vaccine-specific) that were successfully incorporated into our Acceptability Matrix, “supporting its relevance as a tool to inform acceptability recommendations for the general public,” with the effect of similar factors common across multiple vaccines for high-risk groups [13]. While there was insufficient evidence on acceptability in high risk groups, healthcare providers and policymakers, the researchers noted to NACI that “incorporation of evidence into the matrix allowed us to estimate which factors are important to consider when making recommendations for vaccines or vaccine preventable diseases.” The researchers indicated that because acceptability can be affected by contextual influences such as an outbreak (where different factors may weigh more or less heavily on vaccine decisions) the Acceptability Matrix should be applied with consideration for the geographical, political, and social contexts in which vaccine recommendations will be made. Furthermore, the review summarized evidence on interventions effective in improving acceptability of different vaccines.

The results of the recent online Canadian survey of vaccine acceptability in the general public and healthcare providers [14] further validated the utility of the Acceptability Matrix and filled gaps in evidence for acceptability in high risk groups and healthcare providers. The categories in the Matrix accurately captured factors influencing acceptability among the general public, high risk groups, and healthcare providers of vaccination in general, and across a spectrum of vaccines. Results from this research, as well as the systematic literature review, will allow Technical Leads to incorporate up-to-date, Canadian-specific research to consider issues with acceptability for specific immunization recommendations. The value of the Acceptability Matrix is apparent in Table 8, where it is populated with examples across different VPDs to identify when a vaccine recommendation may be more or less acceptable for different groups.

Our Acceptability Matrix was applied in NACI’s Updated Recommendations on the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines [15] . The committee recognized that perceptions of the 2-dose RZV vaccine using new technology with increased reactogenicity would affect acceptability: “LZV has been used around the world for longer than RZV. Real world experience with RZV and the AS01B adjuvant is limited and may affect acceptability…Increased reactogenicity in RZV may affect compliance with the second dose.” After considering the traditional scientific and programmatic factors, the committee still recommended RZV. As summarized in Table 8, while concern about potential side effects is the main reason why 21% of Canadians are reluctant to vaccinate, vaccine effectiveness has the largest influence on the choice of vaccine [14]. The Management Options Table (Table 9) considers acceptability in the context of other factors - while RZV is more reactogenic than LZV, its efficacy is much higher (over 90%). Moreover, acceptability of Zoster vaccination may be increased because the target groups are among those considered most in need of vaccination (immunocompromised people 69%, seniors 65%) [14]. The guidance also suggests evidence-informed interventions that could improve acceptability such as reminder systems, offering a publicly funded program, and healthcare provider recommendations [13].

8. Conclusion

The EEFA Framework and supporting evidence-informed tools (Ethics Integrated Filters, Equity Matrix, Feasibility Matrix and Acceptability Matrix) facilitate the systematic consideration of programmatic factors critical for comprehensive immunization program decision-making and successful implementation of recommendations. Our Framework has been successfully applied in various NACI guidance documents since 2018. Canadian stakeholder feedback has been positive, noting that the tools are “comprehensive”, “relevant”, and “appropriate”. Research, particularly in the fields of vaccine acceptability and equity, has validated the utility and comprehensiveness of the matrices, and found that both existing and emerging evidence can be streamed into these matrices, allowing for an estimation of the factors important to consider when making recommendations for vaccines or vaccine preventable diseases.

The resources and time taken to develop and populate these evidence-informed tools over five years of extensive background work reduces the time and resources required to implement them. We have found this to be true through the successful use of the Framework to inform rapid guidance in less than one month including technical input, presentation to a VPD Working Group under NACI, and incorporation into an ACS. Without such tools, vaccine guidance is delayed, as research to assess these programmatic factors would be required for each immunization recommendation. Most EEFA considerations apply to immunization in general and are supported in the research leading up to the development of the Framework. Only distinct issues unique to a particular vaccine not already assessed in the background work, that could have a significant change in or impact on a recommendation or its implementation, and warrant additional time and resources to investigate will require further exploration. To date, evidence collected in the years leading up to the implementation of the EEFA Framework has been sufficient, additional research related to a specific vaccine recommendation has not been required, and guidance has not been delayed. Additional research may be required, for example, for a new vaccine protecting against a novel virus in a pandemic (e.g. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19), because acceptability is affected by contextual influences where different factors may weigh more or less heavily on vaccine decisions [13]. In this case, the EEFA Framework and supporting tools are still effective to systematically consider critical factors, direct additional research where gaps exist, and enable more efficient assessment.

Specific issues that come to the fore through the use of the EEFA Framework that could have an impact on decision-making or the successful implementation of a recommendation are summarized along with evidence on the traditional scientific factors and economic analyses in NACI guidance documents clearly and transparently (e.g. in Management Options Tables or in GRADE EtD tables [10]).

The use of the EEFA Framework upholds the principles of timeliness, transparency, and clarity deemed critical for NACI guidance, while ensuring that recommendations are appropriate, comprehensive, and based on the full spectrum of public health science. It also empowers the committee to review and balance all of the evidence and summarize their rationale for a recommendation transparently. The tools succinctly and comprehensively outline the questions that need to be answered and the factors that should be considered to ensure that ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability of expert committee guidance are adequately integrated. Advisory bodies around the world may use our EEFA Framework and supporting tools to guide the assessment of prospective vaccines for viable inclusion in immunization programs and meet the global objective of practical, evidence-informed immunization guidance.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Advisory Committee on Immunization 2, the NACI Evidence-based Methodology Working Group 3, the Canadian Immunization Committee 4, the NACI Secretariat 5, and all stakeholders mentioned in this article for their expertise and input. We also thank Ms. Siobhan Kelly and Ms. Christine Mauviel for their project management expertise.

Footnotes

Strategic Advisory Group of Experts at WHO - SAGE, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in the United States - ACIP, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control in the European Union - ECDC, Standing Committee on Immunization in Germany - STIKO, Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation in the United Kingdom - JCVI, Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation in Australia - ATAGI, Comité technique des vaccinations in France - CTV

NACI Members: Dr. C. Quach (Chair), Dr. S. Deeks (Vice-Chair), Dr. N. Dayneka, Dr. P. De Wals, Dr. V. Dubey, Dr. R. Harrison, Dr. K. Hildebrand, Dr. M. Lavoie, Dr. C. Rotstein, Dr. M. Salvadori, Dr. B. Sander, Dr. N. Sicard, Dr. S. Smith.Liaison Representatives: Ms. L. M. Bucci (Canadian Public Health Association), Dr. E. Castillo (Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada), Dr. A. Cohn (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States), Ms. L. Dupuis (Canadian Nurses Association), Dr. J. Emili (College of Family Physicians of Canada), Dr. D. Fell (Canadian Association for Immunization Research and Evaluation), Dr. R. Gustafson (Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health), Dr. D. Moore (Canadian Paediatric Society), Dr. M. Naus (Canadian Immunization Committee), and Dr. A. Pham-Huy (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada).Ex-Officio Representatives: Ms. E. Henry (Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Infectious Diseases [CIRID], Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]), Dr. J. Gallivan (Marketed Health Products Directorate, HC), Ms. M. Lacroix (Public Health Ethics Consultative Group), Ms. J. Pennock (CIRID, PHAC), Dr. R. Pless (Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate, Health Canada [HC]), Dr. G. Poliquin (National Microbiology Laboratory, PHAC), Dr. C. Rossi (National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces), and Dr. T. Wong (First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Indigenous Services Canada).

NACI Evidence-based Methodology Working Group Members: Dr. N. Sicard (Chair), Dr. S. Ismail (Primary Lead), Ms. S. Kelly and Ms. C. Mauviel (Project Officers), Dr. J. Emili and Dr. C. Mah (Liaison Representatives), Drs. C. Greenaway, J. Langley, B. Seifert, B. Warshawsky, W. Carr (External Experts), and PHAC representatives (K. Hardy, A. Sinilaite, Dr. M. Tunis, M. Yeung, K. Young, Dr. L. Zhao)

Canadian Immunization Committee Members: E. Adkins-Taylor, J. Barrett-Ives, J. Boutilier, C. Drummond, D. Falck, B. Hanley, E. Henry, T. Hilderman, A. Hunt, R. Lerch, C. Muecke, Dr. M. Naus, C. O ’Brien, E. Schock, Dr. N. Sicard, R. Tuchscherer, A. Tucker

NACI Secretariat: A. House, Dr. M. Tunis, Dr. O. Baclic, Dr. S. Ismail, Dr. R. Stirling, Dr. L. Zhao, M. Patel, K. Hardy, Dr. A. Killikelly, A. Sinilaite, K. Young, M. Yeung, C. Jensen, L. Coward, R. Goddard, S. Kelly, M. Laplante, M. Matthieu-Higgins, C. Mauviel, B. Sader.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization Press; 2013. 77 p. ISBN: 978 92 4 150498 0.

- 2.Erickson L.J., De Wals P., Farand L. An analytical framework for immunization programs in Canada. Vaccine. 2005;23:2470–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2019. Ten threats to global health in 2019; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- 4.Ismail S.J., Langley J.M., Harris T.M., Warshawsky B.F., Desai S., FarhangMehr M. Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): Evidence-based decision-making on vaccines and immunization. Vaccine. 2010;28:A58–A63. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Immunization Committee. Summary of Canadian Immunization Committee (CIC) Recommendations for Human Papillomavirus Immunization Programs. Canadian Communicable Disease Report 2014;40(8):152-3. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v40i08a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Canadian Immunization Committee. Recommendations for Rotavirus Immunization Programs. Canadian Communicable Disease Report 2014;40(2):13-4. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v40i02a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Canadian Immunization Committee. Summary of the Canadian Immunization Committee (CIC) Recommendations for Zoster Immunization Programs. Canadian Communicable Disease Report 2014;40(9):170-1. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v40i09a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Public Health Agency of Canada. Evidence-based recommendations for immunization: Methods of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Canadian Communicable Disease Report 2009;35(1). 10 p. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2009-35/methods-national-advisory-committee-immunization.html [PubMed]

- 9.Burchett H.E.D., Mounier-Jack S., Griffiths U.K., Mills A.J. National decision-making on adopting new vaccines: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moberg J., Oxman A.D., Rosenbaum S., Schünemann H.J., Guyatt G., Flottorp S. The GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Assessing the programmatic suitability of vaccine candidates for WHO prequalification. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2015. 30 p. ISBN: WHO/IVB/14.10.

- 12.Hoffmann-Eßer W., Siering U., Neugebauer E.A.M., Brockhaus A.C., Lampert U., Eikermann M. Guideline appraisal with AGREE II: systematic review of the current evidence on how users handle the 2 overall assessments. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gates A, Gates M, Rahman S, Guitard S, MacGregor T, Pillay J, et al. A systematic review of factors that influence the acceptability of vaccines among Canadians. Vaccine Submitted November 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Environics Research. Vaccine acceptability factors for the general public and health care professionals in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2020. ISBN: 978-0-660-32602-3.

- 15.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Updated Recommendations on the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. 179 p. ISBN: 978-0-660-25852-2.

- 16.World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2019. Health topics: Health equity; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/topics/health_equity/en/.

- 17.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Update on Immunization in Pregnancy with Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Reduced Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. 34 p. ISBN: 978-0-660-25133-2.

- 18.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Update on the use of pneumococcal vaccines in adults 65 years of age and older – A Public Health Perspective. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. 93 p. ISBN: 978-0-660-27296-2.

- 19.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Interim Statement on the Use of the rVSV-ZEBOV Vaccine for the Prevention of Ebola Virus Disease. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; In Press.

- 20.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Supplemental Statement on Mammalian Cell-Culture Based Influenza Vaccines. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; In Press.

- 21.National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). An Advisory Committee Statement: Statement on Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2020–2021. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; In Press.

- 22.Schmader K.E., Oxman M.N., Levin M.J., Johnson G., Zhang J.H., Betts R. Persistence of the efficacy of zoster vaccine in the shingles prevention study and the short-term persistence substudy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1320–1328. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oxman M.N., Levin M.J., Arbeit R.D., Barry P., Beisel C., Boardman K.D. Vaccination against herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(SUPPL. 2):S228–S236. doi: 10.1086/522159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. New Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271,2284+2365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.McDonald B.M., Dover D.C., Simmonds K.A., Bell C.A., Svenson L.W., Russell M.L. The effectiveness of shingles vaccine among Albertans aged 50 years or older: A retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2017;35(50):6984–6989. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutradhar S.C., Wang W.W.B., Schlienger K., Stek J.E., Chan J.X.S.F., Silber J.L. Comparison of the levels of immunogenicity and safety of zostavax in adults 50 to 59 years old and in adults 60 years old or older. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16(5):646–652. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00407-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lal H., Cunningham A.L., Godeaux O., Chlibek R., DiezDomingo J., Hwang S.J., et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2015 28 May 2015;372(22):2087-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lal H., Cunningham A.L., Kovac M., Chlibek R., Hwang S-., Díez-Domingo J. Efficacy of the herpes zoster subunit vaccine in adults 70 years of age or older. New Engl. J. Med. 2016;375(11):1019–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chlibek R, Smetana J, Pauksens K, Rombo L, Van den Hoek JAR, Richardus JH, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of three different formulations of an adjuvanted varicella-zoster virus subunit candidate vaccine in older adults: A phase II, randomized, controlled study. Vaccine. 2014 26 Mar 2014;32(15):1745–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lal H., Poder A., Campora L., Geeraerts B., Oostvogels L., Vanden Abeele C. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and safety of 2 doses of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine administered 2, 6 or 12 months apart in older adults: Results of a phase III, randomized, open-label, multicenter study. Vaccine. 2018;36(1):148-154. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Public Health Agency of Canada. Framework for ethical deliberation and decision-making in public health a tool for public health practitioners, policy makers and decision-makers. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2017. 23 p. ISBN: 978-0-660-09146-4.

- 32.Top K.A., Esteghamati A., Kervin M., Henaff L., Graham J.E., Macdonald N.E. Governing off-label vaccine use: an environmental scan of the Global National Immunization Technical Advisory Group Network. Vaccine. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neels P., Southern J., Abramson J., Duclos P., Hombach J., Marti M. Off-label use of vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;35:2329–2337. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans T., Brown H. Road traffic crashes: operationalizing equity in the context of health sector reform. Injury Control Saf. Promot. 2003;10:11–12. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.11.14117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welch V., Petticrew M., Tugwell P., Moher D., O’Neill J., Waters E. Extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012;2012:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochrane Methods [Internet]. London (UK): Cochrane; N.D. PROGRESS-Plus; N.D. [cited 2019 Dec 17]. Available from: https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/projects/evidence-equity/progress-plus.

- 37.Quinn S.C., Kumar S. Health inequalities and infectious disease epidemics: a challenge for global health security. Biosecurity Bioterrorism. 2014;12:263–273. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2014.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]