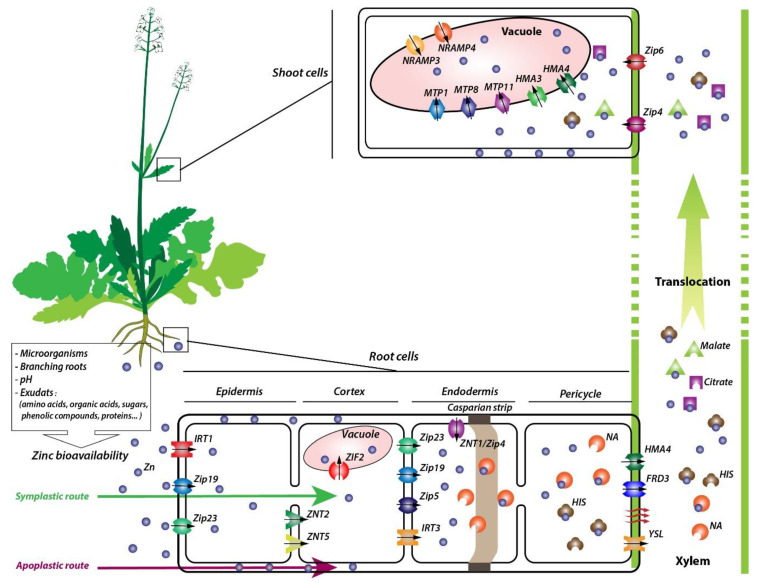

Figure 1.

A model of the mechanisms that occur in hyperaccumulation plants upon exposure to zinc (Zn): Zn ion uptake, chelation, transport, and sequestration. Zn bioavailability can be influenced by several factors, such as microorganisms, branching roots, pH, and exudates. Once adsorbed by the roots, Zn can be absorbed by an apoplastic route: A passive diffusion through cells, or by a symplastic route via transporters. Within the latter path, Zn absorption by epidermis cells is mainly promoted by IRT1, ZIP19, and ZIP23. To reach the cortex, Zn can be directly diffused or by means of ZNT2 and ZNT5. Then, Zn can either be stocked in vacuoles (promoted by ZIF2) or transported to the endodermis through the following transporters: ZIP23, ZIP19, ZIP5, and IRT3. Zn following the apoplastic route is stopped by the casparian strip, and then enters the endodermis via ZNT1/ZIP4. At this level, Zn can be chelated by nicotianamine (NA) or directly diffused to pericycle cells where a part can also be associated to histidine (His). The unchelated Zn can reach the xylem through direct diffusion or via YSL, ferric reductase defective 3 (FRD3,) and HMA4. Zn then crosses the xylem as a Zn-free form or coupled with His, citrate, or malate. To enter the leaf cells, Zn can passively penetrate in chelated forms or as the Zn-free form via ZIP4 and ZIP6 proteins. It is then sequestrated inside the vacuole through MTP1 (metal tolerance proteins 1), MTP8, MTP11, NRAMP3, NRAMP4, HMA3, and HMA4 transporters, or blocked in the cell wall.