Figure 3. DNA distortion in the R-loop flank facilitates target-strand cleavage.

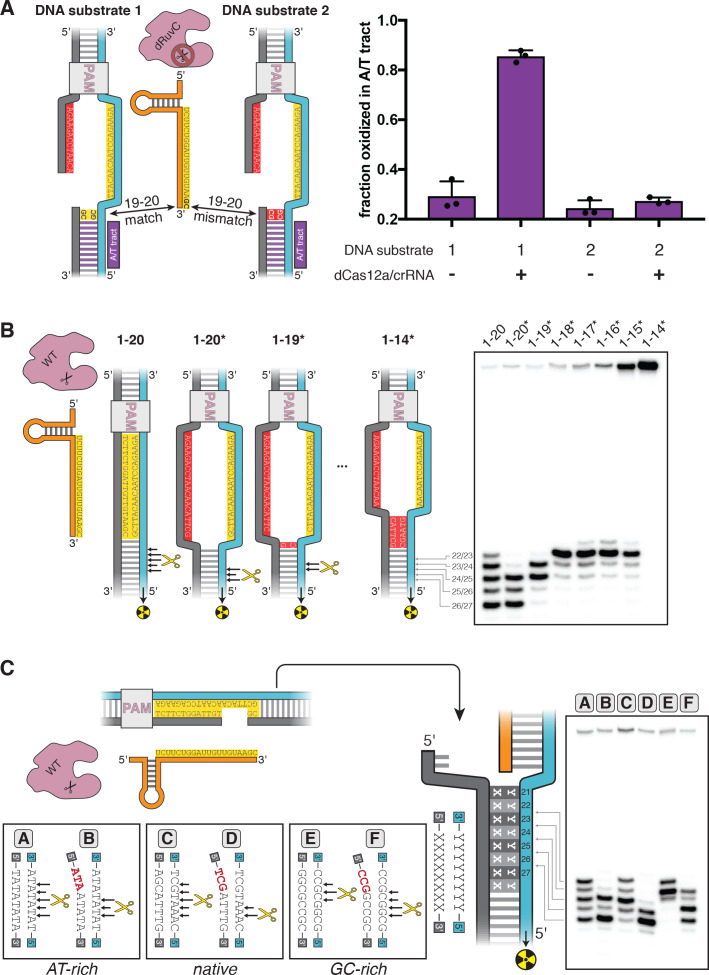

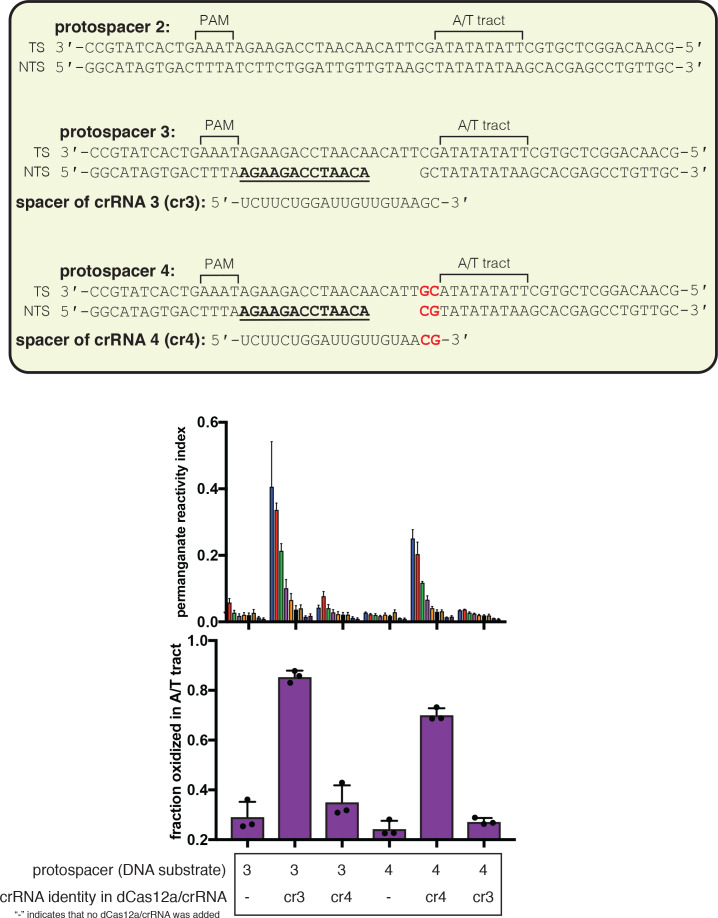

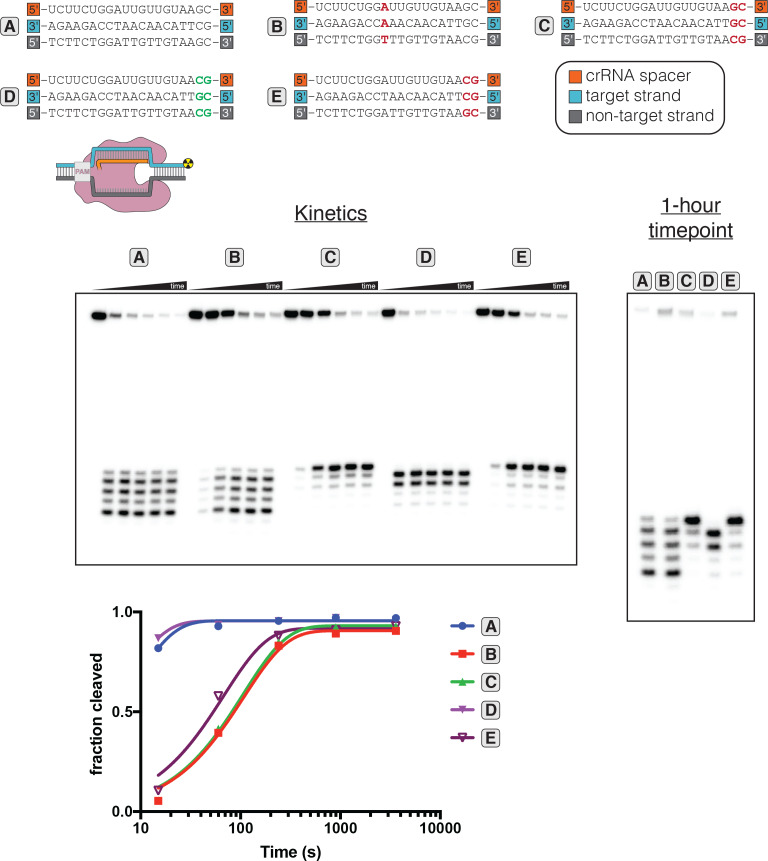

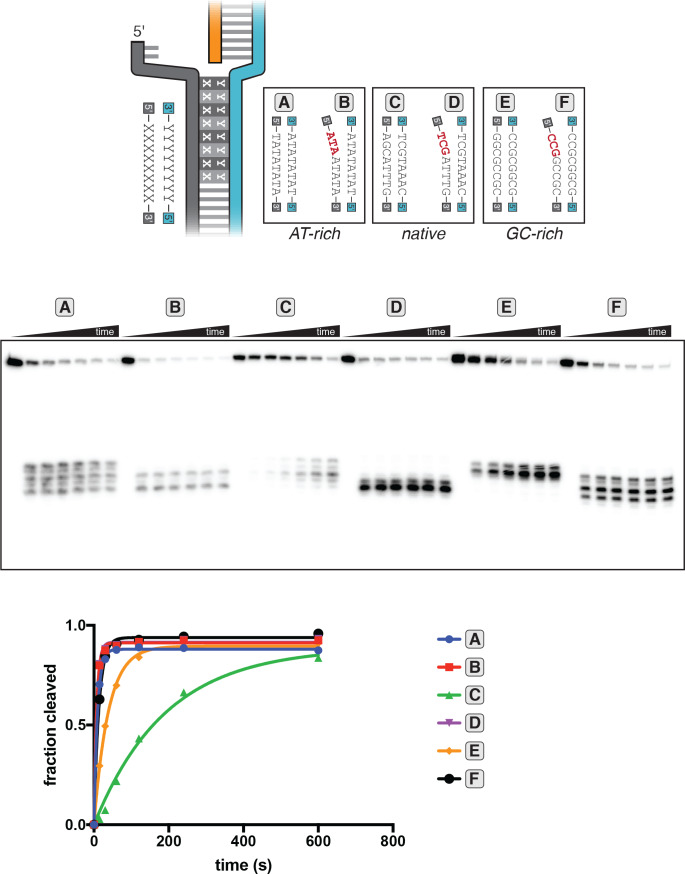

(A) Permanganate reactivity of A/T tract in a 20-nt R-loop and an 18-nt R-loop. Permanganate experiments were conducted as in Figure 2B (2 minutes, 30°C). Purple rectangles alongside DNA schematics indicate the location of the tract of DNA whose permanganate reactivity is being quantified. The y-axis denotes the fraction of DNA molecules estimated to have been oxidized on at least one thymine within the A/T tract (see Materials and methods). Columns and associated error bars indicate the mean and standard deviation of three replicates. (B) Target-strand cut-site distribution with a shrinking R-loop, as resolved by denaturing PAGE and phosphorimaging (n = 3). 100 nM AsCas12a and 120 nM crRNA were incubated with 1 nM of DNA target at 37°C for 1 hr, prior to quenching and resolution by denaturing PAGE (kinetics shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 4). Each lane corresponds to a different DNA target, bearing varying numbers of PAM-distal mismatches with respect to the crRNA. Indicated above each lane is the number of base pairs of complementarity between the target strand and the crRNA spacer, starting with the base immediately adjacent to the PAM. For the lane lacking an asterisk, the DNA target was fully duplex. For the lanes that bear asterisks, the DNA target contained a bubble across the region of crRNA:TS complementarity, which stabilized the interaction of the DNA with the Cas12a/crRNA complex. Numbers to the left of the phosphorimage indicate the position (distance from the PAM, as numbered in C) of the dinucleotide whose phosphodiester was cleaved to yield the labeled band. Black arrows are drawn on the substrate diagrams to indicate cleaved phosphodiesters (as determined from the phosphorimage), and relative arrow lengths are roughly reflective of relative band intensities. (C) Target-strand cut-site distribution with various sequences in the R-loop flank (all with a 20-nt R-loop), as resolved by denaturing PAGE and phosphorimaging (n = 3). 100 nM AsCas12a and 120 nM crRNA were incubated with 1 nM of DNA target at 25°C for 10 min, prior to quenching and resolution by denaturing PAGE (kinetics shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 7). All DNA targets were 5'-radiolabeled on the target strand. The non-target strand contained a gap from positions 14–18 (see Appendix 2) but was complementary to the target strand at positions 1–13 and 19–20. In each lane, the DNA target was varied to contain different sequences in the R-loop flank, which either formed a perfect duplex (substrates A, C, and E) or contained a 3-bp NTS:TS mismatch (substrates B, D, and F). Black arrows are drawn on the substrate diagrams as in B.

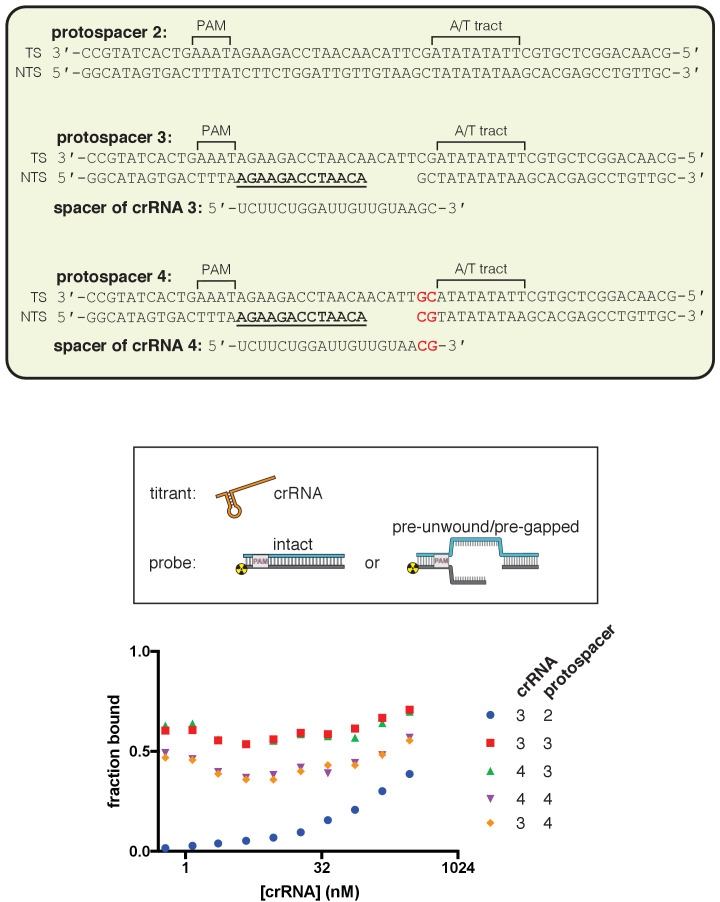

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. dCas12a ribonucleoprotein binds tightly to pre-gapped/pre-unwound targets despite PAM-distal mismatches.

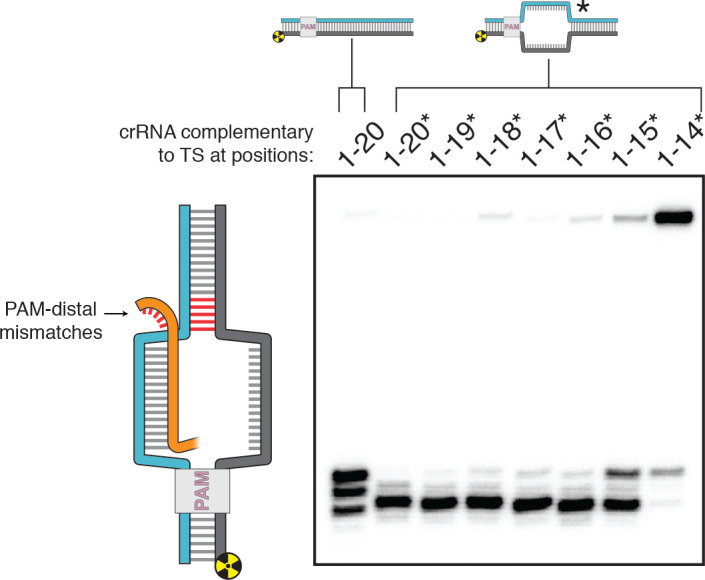

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Effect of R-loop truncation on permanganate reactivity of the A/T tract.

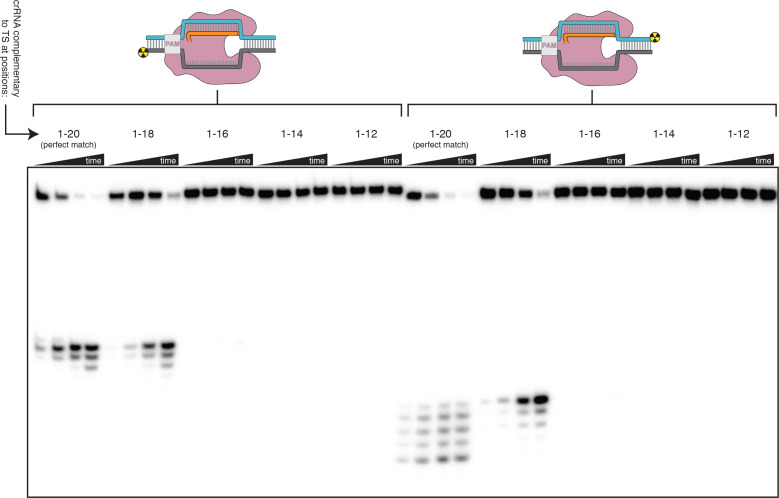

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Effect of PAM-distal mismatches on non-target-strand and target-strand cleavage kinetics and position with fully duplex DNA targets.

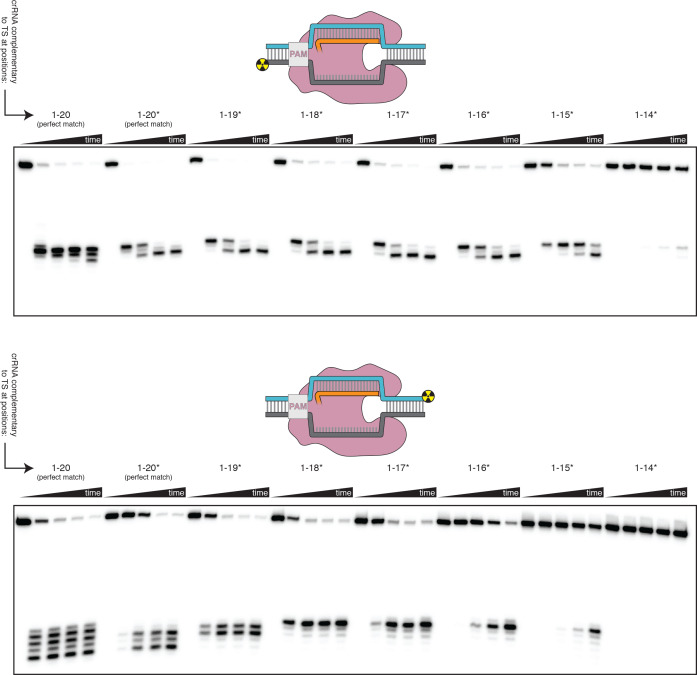

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. Effect of PAM-distal mismatches on non-target-strand and target-strand cleavage kinetics and position with bubbled DNA targets.

Figure 3—figure supplement 5. Determinants of altered target-strand cleavage kinetics and position.

Figure 3—figure supplement 6. Non-target-strand cut-site distribution with a shrinking R-loop.