Abstract

Despite recent recognition of the ATP-binding cassette protein OptrA as an important mediator of linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecalis worldwide, the mechanisms of optrA gene acquisition and transfer remain poorly understood. In this study, we performed comprehensive molecular and phenotypic profiling of 44 optrA-carrying E. faecalis clinical isolates with linezolid resistance. Pulse-field gel electrophoresis and DNA hybridization revealed the presence of optrA in the plasmid in 26 (59%) isolates and in the chromosome in 18 (41%) isolates. Conjugation experiments showed a successful transfer of optrA in 88.5% (23/26) of isolates carrying optrA in plasmids while no transfer occurred in any isolates carrying optrA in the chromosome (0/18). All 23 transconjugants exhibited in vitro resistance to linezolid and several other antibiotics and were confirmed to contain optrA and other resistance genes. Plasmid typing demonstrated a predominance (18/23,78%) of rep9–type plasmids (pCF10 prototype) known to be the best studied sex pheromone responsive plasmids. Full plasmid genome sequencing of one isolate revealed the presence of drug resistance genes (optrA and fexA) and multiple sex pheromone response genes in the same plasmid, which represents the first sex pheromone responsive plasmid carrying optrA from a clinical isolate. PCR-based genotyping revealed the presence of three key sex pheromone response genes (prgA, prgB, and prgC) in 23 optrA-carrying isolates. Finally, functional studies of these isolates by clumping induction assay detected different degrees of clumping in 17 isolates. Our analysis suggests that optrA-mediated linezolid resistance can be widely disseminated through sex pheromone plasmid transfer.

Keywords: linezolid, Enterococcus faecalis, optrA, transmission, sex pheromone plasmid

Introduction

Enterococcus faecalis is an opportunistic pathogen that resides primarily in the gastrointestinal tract of most healthy individuals, but can cause urinary tract infections, surgical infections and even fatal infections, such as endocarditis and bacteremia (Arias and Murray, 2012; Beganovic et al., 2018). Its high-level intrinsic and acquired resistance to multiple drugs, especially vancomycin, has limited the treatment options (Mundy et al., 2000; Paulsen et al., 2003). There is a clear need to better understand the mechanisms of drug resistance and its transmission in order to develop effective strategies to monitor and control drug resistance.

Linezolid, the first member of oxazolidinone antibiotic antibacterial agents, was approved for clinical therapy in 2000 as the last-resort drug for treatment of serious Gram-positive bacterial infections, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and multi-drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (Leach et al., 2011). The increasing prevalence of linezolid-resistant E. faecalis presents a formidable challenge to clinical treatment (Farrell et al., 2011; Deshpande et al., 2018). The common mechanisms of linezolid resistance in E. faecalis include point mutations in the chromosomal 23S rRNA gene or protein-coding genes encoding the L3 and L4 ribosomal proteins (Bi et al., 2018; Deshpande et al., 2018). Other newly identified mechanisms include the presence of plasmid-borne chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance (cfr) gene (Schwarz et al., 2000) or ribosomal protection genes optrA (Wang et al., 2015) and poxtA (Antonelli et al., 2018).

The optrA gene encodes the ATP-binding cassette F (ABC-F) protein and mediates resistance to phenicols and oxazolidinones through protection of the bacterial ribosome from antibiotic inhibition (Wang et al., 2015; Sharkey et al., 2016). Following the first report of the optrA gene in 2015 from an E. faecalis isolate obtained from a blood sample of a Chinese patient (Wang et al., 2015), optrA has been found worldwide not only in E. faecalis and E. faecium (Cai et al., 2015; Mendes et al., 2016; Cavaco et al., 2017; Gawryszewska et al., 2017; Càmara et al., 2019; Said and Abdelmegeed, 2019; Sassi et al., 2019; Tsilipounidaki et al., 2019) but also in other Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus sciuri (Fan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016) and Streptococcus suis (Huang et al., 2017). In addition, optrA has been detected not only in various human clinical samples but also in diverse livestock samples such as cow milk, and feces or meat from pigs, chicken and ducks (Elghaieb et al., 2019; Na et al., 2019) as well as environmental samples such as soils (Zhao et al., 2016) and urban wastewater (Freitas et al., 2017). Search of the PubMed database using optrA as the keyword in the abstract identified 2, 10, 15, 23, and 35 papers from 2015 to 2019, respectively, with the geographic origin of these reports expanded from only one country (China) in 2015 to 19 countries (from five continentals) in 2019. Such rapid, widespread dissemination of this resistance gene suggests a highly efficient dissemination capacity among animals, humans, and the environment.

Indeed, there have been reports of easy transfer of optrA-carrying plasmids at high transfer frequencies of 10–2–10–6 in vitro between E. faecalis and E. faecium (Wang et al., 2015) and between human- and pig-derived E. faecalis (Shang et al., 2019). Our previous transcriptomics (Hua et al., 2018) and proteomics (Yan et al., 2018) analyses of a linezolid-resistant E. faecalis strain P10748 consistently revealed a significant co-upregulation of optrA gene with several genes involved in mating and pheromone response, implying a localization of this gene in a sex pheromone plasmid allowing highly efficient resistance transfer. However, the location of the optrA gene and the sequences of the plasmid and chromosome of this strain have not yet been determined.

The goals of this study were to assess the distribution and transferability of the optrA gene in a case series of E. faecalis clinical isolates, determine the whole plasmid genome sequence in the linezolid-resistant E. faecalis strain P10748, and identify mechanisms behind optrA transfer. Our results suggest, for the first time, that optrA-mediated linezolid resistance can be widely disseminated through sex pheromone plasmid transfer.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

A panel of 44 linezolid-resistant E. faecalis isolates was obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China (Hua et al., 2019). All isolates showed minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) > 4 mg/L of linezolid as determined by the broth microdilution method following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2018) recommendations. The drug resistance phenotypes and multi-locus sequence types (MLST) of all these isolates have been determined in our previous study (Hua et al., 2019; Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). The E. faecalis ATCC 29212 isolate obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, United States) served as a quality control strain. E. faecalis JH2-2 isolate was kindly provided by Dr. Tieli Zhou (The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, China) and used as the recipient strain in conjugation experiments.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of linezolid-resistance plasmids in 26 E. faecalis isolates carrying optrA.

| Isolate ID | Plasmid size (kb) | Rep-familya | Prototypea | Transferred resistance genea | MICs of linezolid (mg/L)b | MLSTc |

| P10748 | ∼54 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST480 |

| EF-3015 | ∼150 | 6, 9 | pS86, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB fexA | 8 | ST828 |

| EF-7013 | ∼60 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST16 |

| EF-8194 | ∼80 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL ermB, lnuB fexA | 8 | ST16 |

| EF-9289 | ∼80 | 1, 7, 9 | pIP501, pUSA02, pAD1 | optrA, tetL, ermB, fexA | 8 | ST826 |

| EF-3139 | ∼100 | 1, 9 | pIP501, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB fexA | 16 | ST386 |

| EF-5136 | ∼80 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB fexA | 8 | ST16 |

| EF-2084 | ∼80 | 1, 9 | pIP501, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST480 |

| EF-0132 | ∼80 | 1, 9 | pIP501, pCF10 | optrA, tetL ermB, lnuB, fexA | 16 | ST585 |

| EF-4003 | ∼55, ∼350d | 7 | pUSA02 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, fexA | 16 | ST16 |

| EF-8042 | ∼30, ∼200d | 1, 9 | pIP501, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, fexA | 8 | ST69 |

| EF-0074 | ∼65 | 7, 9 | pUSA02,pAD1 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST826 |

| EF-6165 | ∼80 | 1 | pIP501 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST823 |

| EF-7094 | ∼40, ∼350d | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST632 |

| EF-1127 | ∼55 | 1, 9 | pIP501, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST824 |

| EF-8137 | ∼80 | 1, 7, 9 | pIP501, pUSA02, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST116 |

| EF-8282 | ∼80 | 6,9 | pS86, pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB | 16 | ST330 |

| EF-4245 | ∼80 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST823 |

| EF-1080 | ∼40 | 9 | pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST69 |

| EF-2216 | ∼80 | 1,9 | pIP501,pCF10 | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST376 |

| EF-6166 | ∼80 | NA | NA | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 16 | ST16 |

| EF-5015 | ∼80 | NA | NA | optrA, tetL, tetM, ermB, lnuB, fexA | 8 | ST480 |

| EF-2021 | ∼90 | NA | NA | optrA, tetL, ermB, lnuB fexA | 16 | ST714 |

| EF-8014 | ∼55 | NT | NT | NT | 8 | ST632 |

| EF-3186 | ∼30 | NT | NT | NT | 8 | ST69 |

| EF-1090 | ∼55 | NT | NT | NT | 8 | ST585 |

aThese results are consistent between transconjugants and original clinical isolates. bAll clinical isolates considered low-level resistance to linezolid (Hua et al., 2019). MIC values for other drugs are listed in Supplementary Table S1. cMulti-locus sequence types determined for original isolates in our previous study (Hua et al., 2019). dTwo plasmids with different sizes. NA, not available in plasmid typing with 19 known rep families. NT, not tested due to negative results in conjugation experiment.

Determination of the optrA Location

To determine the location of optrA, S1 nuclease-pulsed field electrophoresis (S1-PFGE) and Southern blot were performed following the methods described previously (Barton et al., 1995; Rosvoll et al., 2010). Briefly, bacterial cells harvested from fresh culture were embedded in agarose gels and then digested by S1 nuclease (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Salmonella Braenderup H9812 chromosomal DNA was digested with XbaI (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and used as the DNA size marker. CHEF electrophoresis was performed using the same conditions described elsewhere (Rosvoll et al., 2010). Following transfer to Hybond N + membranes (Amersham Biosciences, United States) by capillary blotting for more than 20 h, blots were hybridized with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled optrA-specific probe using the DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Conjugation Experiments and Detection of Resistance Genes

To examine the transferability of plasmids containing optrA, filter mating was conducted on nitrocellulose filters (0.45 μm pore size, Millipore, United States) as described previously (Werner et al., 2003). Rifampicin-resistant E. faecalis JH2-2 was used as a recipient strain and optrA-positive E. faecalis was used as a donor strain. The donor and recipient strains were cultured to the exponential growth phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.6) and then mixed at a ratio of 1:3. The mixture was shaken for 30 min and centrifuged. The pellet was placed on a filter for overnight incubation at 37°C. Transconjugants were selected on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with 25 mg/L of rifampin and 10 mg/L of florfenicol. Subsequently, the selected transconjugants were subjected to confirmation of the presence or absence of the optrA gene and the resistance to rifampicin and florfenicol. The use of florfenicol instead of linezolid for selecting transconjugants was based on the observation of a larger difference for florfenicol than for linezolid in MIC values (4 vs. 64 mg/L) between the donor and recipient bacteria. Approximately 20–150 colonies were obtained from each transconjugation reaction, with 2–5 of them selected for PCR analysis.

To detect the transmission of resistance in transconjugants, antimicrobial susceptibility of the transconjugants were determined as described above. The presence of known potential antibiotic resistance genes including tetM, tetL, ermB, lnuB and fexA, were screened by PCR amplification using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. Positive PCR products were sequenced commercially by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Resulting sequences were analyzed using MegAlign (version 7.1.0, DNASTAR, United States) and compared with reference sequences in the NCBI nucleotide database.

Plasmid Replicon Typing

On the basis of plasmid classification schemes by Jensen et al. (2010), we designed PCR primers to detect 19 different types of rep-family plasmids (rep1–11, rep13–19 and repunique) in E. faecalis transconjugants. Rep12 family was not included owing to lacking a reference strain. All samples were first screened by multiplex PCR, followed by single-locus PCR for samples that were not clearly differentiated in multiplex PCR. All positive PCR products were sequenced commercially and analyzed against sequences of known rep-families in the NCBI nucleotide database. In addition to transconjugants, the rep-types in all original isolates were also assessed by the same PCR method.

Sequencing and Analysis of the Whole Plasmid Genome in P10748 Harboring optrA

The whole plasmid genome in the E. faecalis strain P10748 was sequenced as a part of the E. faecalis genome sequencing project [U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, United States) BioProject accession no. PRJNA629062]. Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight culture using the Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Five micrograms of DNA were used to construct one Illumina library and sequenced using 250 base paired-end reads on the Illumina HiSeq platform commercially (Novogene Corporation, Hong Kong). A total of 20 million reads were obtained. After removal of low-quality reads and reads for E. faecalis nuclear genome sequences (GenBank accession no. CP008816), the remaining 285,862 reads were assembled using SeqMan NGen (version 14.1.0.118, DNASTAR, Madison, WI, United States), resulting in a circular assembly of the complete plasmid genome. This assembly was validated by PCR and Sanger sequencing of multiple overlapping fragments, and by restriction mapping using NheI.

Gene prediction was conducted through a combination of multiple computational programs including GeneMarkS (Besemer et al., 2001), RAST (Aziz et al., 2008), ORF Finder1 and BLAST2.

Distribution of Key Sex-Pheromone-Response Genes in optrA-Carrying E. faecalis Isolates and Their Transconjugants

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures using the HiPure Bacterial DNA Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The presence of three key sex-pheromone-response genes (prgA, prgB, and prgC) in the donor and transconjugant strains was determined by PCR using primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. All positive PCR products were sequenced and the resulting sequences were blasted against the NCBI nucleotide database.

Determination of Sex Pheromone Responses by Clumping Induction Assay (CIA)

Clumping induction assay (CIA) was performed as described previously (Donelli et al., 2004). Pheromone-containing filtrates were prepared from E. faecalis JH2-2 strain grown overnight in BHI broth (referred to as the recipient strain). The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. The filtrates were autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min, and stored at 4°C before use. E. faecalis culture (from clinical isolates or their transconjugants, referred to as the donor strain) was added to pheromone-containing filtrate, followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h with shaking. To test the type of sex pheromones involved in mating, synthetic sex pheromone cAD1 or cCF10 (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used at the final concentration of 100 ng/ml instead of JH2-2-derived filtrates described above (Lim et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2009). Degrees of cell clumping were semi-quantitated as titers for visible cell aggregates.

Quantification of Transfer Frequencies for Plasmid pEF10748 by Short Mating Assay

Short mating induced by the pheromone was performed as described previously (Lim et al., 2006). After 45-min pheromone induction, 0.1 ml of the donor strain (P10748) was mixed with 0.9 ml of the recipient strain E. faecalis JH2-2, followed by incubation for 15 min at 37°C. The mixture was then plated on selective plates containing 25 mg/L of rifampin and 10 mg/L of florfenicol.

Results

Localization of optrA Gene in the Linezolid-Resistant E. faecalis

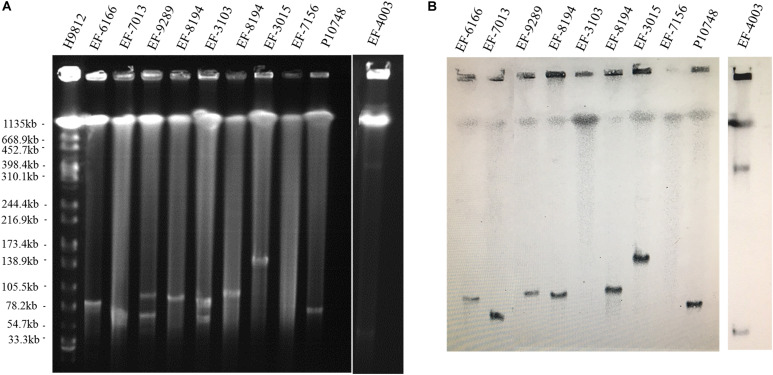

Among 44 linezolid-resistant E. faecalis isolates analyzed by S1-PFGE, optrA was localized on the plasmid in 26 (59%) isolates and on the chromosome in 18 (41%) isolates. The size of plasmids varied from 30 to 300 kb (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). Of the 26 isolates with optrA-carrying plasmids, 23 had a single plasmid and the remaining 3 had a co-existence of two plasmids with different sizes (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Determination of the location of optrA in linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis isolates. (A) Representative results of S1 nuclease-pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis. The first lane contained XbaI-digested chromosome of Salmonella Braenderup H9812 as a DNA size marker. (B) Representative results of Southern hybridization showing the location of optrA in plasmids or chromosomes. IDs of individual isolates analyzed are indicated at the top.

Horizontal Transmission of optrA Gene

In conjugation experiments with E. faecalis JH2-2 as a recipient, positive transfer of the optrA gene was achieved in 23/26 (88.5%) E. faecalis clinical isolates with optrA-carrying plasmids. The transfer frequencies varied from 10–3 to 10–6 per donor cell. The other three isolates showed no transfer despite multiple attempts. None of the 18 isolates containing optrA in the chromosome showed positive transfer. In drug susceptibility testing of the 23 transconjugants, the MIC value of linezolid was 8–16 mg/L whereas the recipient strain was 2 mg/L. In addition, these 23 transconjugants exhibited resistance to chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline compared with the recipient strain E. faecalis JH2-2 (data not shown). By PCR, in each of the 23 transconjugants we detected multiple resistance genes, including optrA (23/23, 100%), tetL (23/23, 100%), tetM (11/23, 47.8%), ermB (22/23, 95.6%), lnuB (20/23, 87.0%), and fexA (22/23, 95.6%) (Table 1). The resistance gene profiles of transconjugants were consistent with those of the donor isolates.

Detection of rep-Families in E. faecalis Transconjugants and Their Original Clinical Isolates

Four types of plasmids were identified by PCR in 20 isolates carrying optrA while other three isolates did not show any of the 19 plasmid types targeted in our study (Table 1). The dominant plasmid type was rep9 family (prototype pCF10), which was detected in 78% (18/23) of isolates. Rep1 (prototype pIP501) accounted for the second major rep-family being identified in 39% (9/23) isolates. rep7 (pIP501 prototype) and rep6 (pIP501 prototype) were detected with lower frequencies (17.4% or 4/23 and 8.7% or 2/23, respectively). Other plasmids including rep2–5 rep8, rep10–11, rep13–16, rep18–19, and the repUnique were not detected in any isolates.

The results of rep types were consistent between transconjugants and their corresponding original isolates. Of the 20 successfully typed isolates, 9 contained a single plasmid type, 9 contained a mixture of two plasmid types and the remaining 2 contained a mixture of three plasmid types (Table 1).

Distribution of Key Sex-Pheromone-Response Genes in optrA-Carrying E. faecalis Isolates and Their Transconjugants

Among the 23 original isolates and their respective transconjugants carrying optrA, 15 were PCR-positive for the prgA gene with both the original isolates and their transconjugants, 5 were positive with the original isolate only, and the remaining 3 were negative (Table 2). In PCR testing for the prgB gene, 21 were positive with both the original isolates and transconjugants, and the remaining 2 were positive with the original isolate only. In PCR testing for the prgC gene, 10 were positive with both the original isolates and transconjugants, 5 were positive with the original isolate only, and the remaining 8 were negative with both the original isolates and transconjugants. Overall, all 23 isolates were positive for at least one of the three key pheromone-response genes with either the original isolates or transconjugants; only seven isolates were positive for all three genes with both the original isolates and transconjugants. prgB was the most common gene, which was detected in all 23 original isolates.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of key sex-pheromone-response genes and results of clumping assay in 23 E. faecalis isolates showing successful transfer of optrA-carrying plasmids.

| Pheromone-response | |||||||

|

genesa |

Clumping assayb |

||||||

| rep9 | prgA | prgB | prgC | cCF10 | cAD1 | JH2-2 filtrate | |

| P10748 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| EF-3015 | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | −/− | 2 | 16 | 2 |

| EF-7013 | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | +/+ | 32 | 32 | 8 |

| EF-8194 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | 64 | 32 | 4 |

| EF-9289 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| EF-3139 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | − | 2 | 2 |

| EF-5136 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | − | − | 2 |

| EF-2084 | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | −/− | − | − | 2 |

| EF-0132 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | 2 | − | 4 |

| EF-4003 | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | − | − | − |

| EF-8042 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | − | − | 2 |

| EF-0074 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | 32 | 64 | 4 |

| EF-6165 | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | − | − | − |

| EF-7094 | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | +/+ | − | − | 2 |

| EF-1127 | +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/− | − | − | 2 |

| EF-8137 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| EF-8282 | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | −/+ | 2 | − | 2 |

| EF-4245 | +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/+ | − | − | 2 |

| EF-1080 | +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/− | 2 | − | 2 |

| EF-2216 | +/+ | −/+ | −/+ | −/+ | − | − | − |

| EF-6166 | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | − | − | − |

| EF-5015 | −/− | +/+ | −/+ | +/+ | − | − | − |

| EF-2021 | −/− | +/+ | +/+ | −/− | − | − | − |

aThe presence (+) or absence (−) in transconjugants/original clinical isolates by PCR. bTiters for visible cell aggregates with original isolates only. The values represent dilution factors from stock concentration, eg., 8 represents 1:8.

Of the 18 original isolates containing a rep9 type of plasmids, all were positive for prgB, 15 were positive for prgA and 13 were positive for prgC. On the other hand, of the 5 original isolates that did not carry a rep9 type of plasmids, all were positive for prgA and prgB while only 2 were positive for prgC.

Determination of Sex Pheromone Responses by CIA

In CIA assay with synthetic pheromones cAD1 and cCF10 as inducers, 11 of 23 optrA-carrying isolates showed different degrees of clumping with at least one inducer, including three showing titers higher than 1:16 and 9 showing titers from 1:2 to 1:16 (Table 2). None of the 5 isolates without a rep9-type plasmid showed apparent clumping. In CIA assay with JH2-2 filtrates, 17 of 23 optrA-carrying isolates (all containing rep9-type plasmids) displayed aggregation with titers from 1:2 to 1:8 while the remaining 6 isolates showed no aggregation.

Quantification of Transfer Frequencies of the Plasmid pEF10748 by Short Mating

Transfer frequencies were determined by short mating assay using induced or uninduced donor E. faecalis containing plasmid pEF10748 and plasmid-free recipient E. faecalis JH2-2 (Table 3). With induced donor cells, the transfer frequency was about 10–4 per donor cell while with uninduced donor cells, the transfer frequency was about 10–8 per donor cell, supporting that the plasmid pEF10748 conferred a pheromone response. Compared to uninduced cells, pEF10748 responded to both cCF10 and cAD1 with higher transfer frequencies (∼10–6), which suggests that pEF10748 functions similarly to the pheromone-responsive plasmids pCF10 and pAD1 (Dunny et al., 1982; Clewell, 2007).

TABLE 3.

Plasmid transfer frequency in E. faecalis isolate P10748 carrying sex pheromone plasmid pEF10748 based on short mating assay.

| Donor | Recipient | Exposure to pheromone | Transfer frequencya |

| P10748 | JH2-2 | - | 2 × 10–8 |

| JH2-2 filtrate | 4 × 10–4 | ||

| cCF10 | 3 × 10–6 | ||

| cAD1 | 1.2 × 10–6 |

aNo. of transconjugants per donor cell.

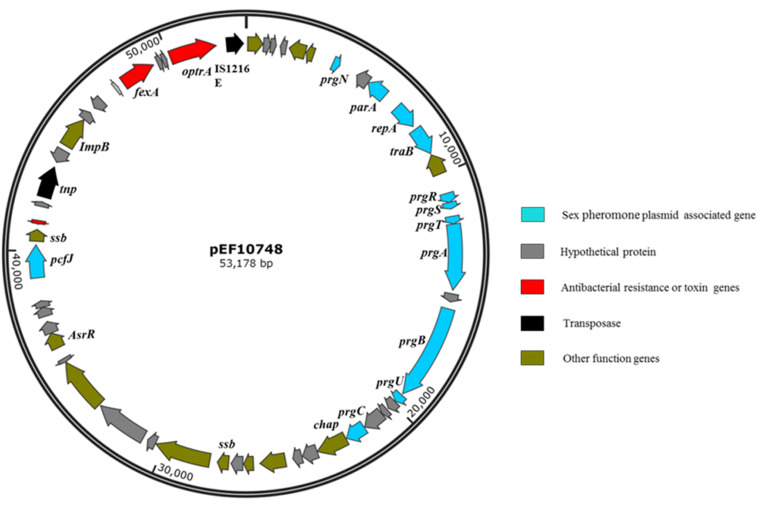

Characteristics of the optrA-Carrying Plasmid in E. faecalis Strain P10748

De novo assembly of Illumina HiSeq data from E. faecalis P10748 resulted in a complete genome of plasmid pEF10748 containing 53,178 bp (GenBank accession no. MK993385.1). This size is consistent with the results of Southern blot (Figure 1), supporting the correct assembly of the plasmid genome. This genome has a GC content of 35%, similar to that of the E. faecalis genome. A total of 58 coding sequences (CDSs) were identified, with the majority of them encoded in the same orientation, similar to known pheromone plasmids in E. faecalis, such as pCF10 (Hirt et al., 2005) and pAD1 (Clewell, 2007). The predicted genes of all CDSs are listed in Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Gene organization in plasmid pEF10748 from the E. faecalis clinical isolate P10748. Arrows indicate the CDSs and their transcription directions. The putative functions of CDSs are color-coded as indicated at the right.

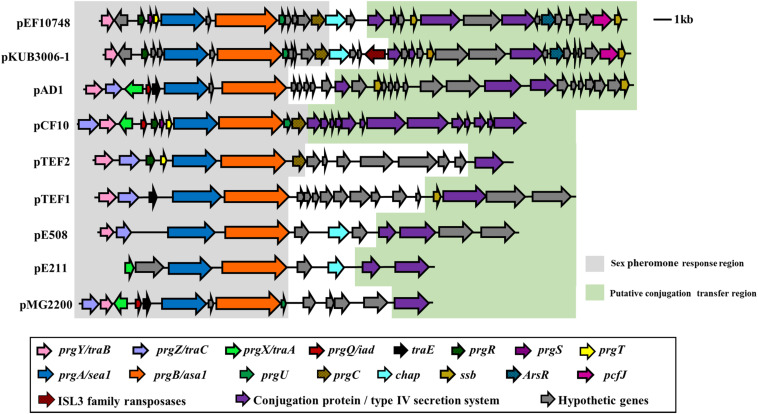

The full-length sequence of plasmid pEF10748 was not identical to any plasmid sequences currently available in GenBank while being most closely related to plasmid pKUB3006-1 in an E. faecalis isolate reported from Japan (Kuroda et al., 2018), with 78% coverage and 99% sequence identity for a ∼42 kb region (Supplementary Table S4). Other plasmids with significant overlap to this region included pTEF1, pAD1, pMG2200, pCF10 and pTEF2 (Figure 3). All these plasmids were identified in E. faecalis from human and swine samples and contain multiple sex pheromone response genes, including traB, prgA (sea1), prgB (asa1), prgC, prgU, prgR, prgS, and prgT.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the sex pheromone gene cluster among known sex pheromone plasmids. Different genes are color-coded as shown in the box on the bottom. Of note, for the region shown, the gene organization in plasmid pEF10748 identified in this study is most similar to that of pKUB3006-1 reported by Kuroda et al. (2018). The bacterial origin and GenBank accession numbers of all plasmids shown are available from Supplementary Table S4.

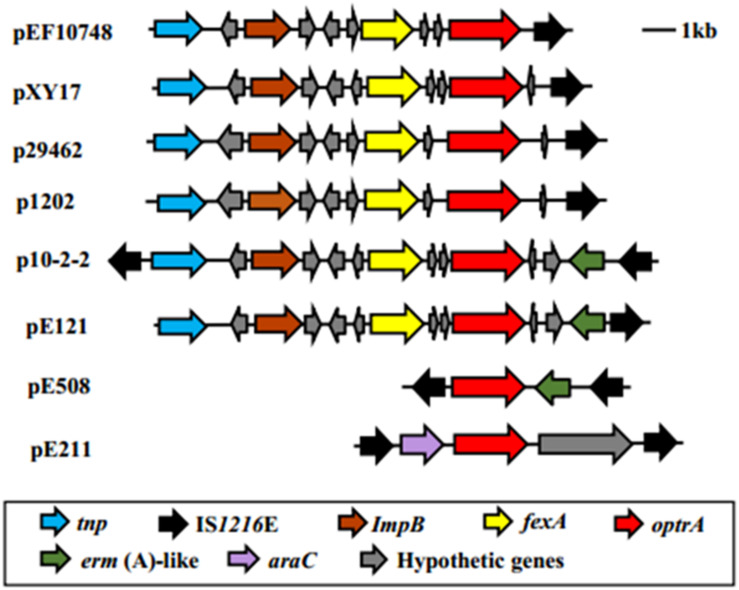

The optrA gene in plasmid pEF10748 was surrounded by chloramphenicol/florfenicol resistance gene fexA, ISL3 transposase, Imp and IS1216E element, all of which were located in a ∼11 kb region (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 2). This region showed highest homology (>99.9% sequence identity) to the following plasmids: pXY17, p10-2-2, p29462, p1202, and pE121 (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 4). All these plasmids were identified from E. faecalis in China.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the genetic environment of the linezolid resistance optrA among different plasmids. Different genes are color-coded as shown in the box on the bottom. Of note, for the region shown, the gene organization in plasmid pEF10748 identified in this study is most similar to that of pXY17 reported by He et al. (2016). The bacterial origin and GenBank accession numbers of all plasmids shown are available from Supplementary Table S4.

Discussion

In this study, we performed comprehensive molecular and phenotypic profiling of 44 E. faecalis clinical isolates with linezolid resistance through combination of PFGE, DNA hybridization, PCR-based genotyping, whole plasmid genome sequencing, antibiotic susceptibility testing, bacterial conjugation and clumping induction assay. Our results strongly suggest that optrA-mediated linezolid resistance can be widely disseminated through sex pheromone plasmid transfer.

Our conclusion on the sex pheromone plasmid transfer mechanism is supported by the following findings.

First, we detected a high prevalence of plasmid-borne optrA gene in E. faecalis clinical isolates. The proportion of isolates carrying optrA in the plasmid was slightly higher than isolates carrying optrA in the chromosome (59 vs. 41%), which is consistent with previous reports in China (Cai et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015) and other countries (Bender et al., 2018; Deshpande et al., 2018; Sassi et al., 2019). It is well-known that plasmids can mediate fast and efficient gene transfer within and between different bacterial host species.

Second, we detected a high transferability (23/26, 88%) of optrA-carrying plasmids based on studying a case series of 26 E. faecalis clinical isolates with linezolid resistance and carrying optrA in plasmids (Table 1). This transferability was confirmed by MIC testing and PCR amplification of multiple genes (drug-resistance genes, rep genes and sex-pheromone-response genes) in all transconjugants. In addition, quantitative study of the isolate E. faecalis P10748 carrying an optrA-containing plasmid revealed a high plasmid transfer frequency (10–4). To our knowledge, this study is the largest to date to assess the transferability of optrA-carrying plasmids in clinical isolates of E. faecalis. Based on the results of drug resistance profiles (Table 1), plasmid replicon typing and distribution of key sex-pheromone-response genes (Table 2), more than a half (13 or 57%) of the 23 transconjugants showed identical patterns as the original isolates, suggesting the likelihood of transferring the same plasmid, while the remaining transconjugants (10 or 43%) showed differences in some properties (e.g., the distribution of 3 key sex-pheromone-response genes) (Table 2), suggesting the likelihood of transferring different genetic materials. Thorough confirmation of the exact transferred materials will require additional experiments such as whole chromosome and plasmid sequencing, and high-resolution PFGE coupled with probe hybridization.

Third, sequencing of the full plasmid genome in one E. faecalis clinical strain (P10748) confirmed the co-localization of optrA with almost all known sex-pheromone response genes, including the typical prgA-prgB-prgC cassette, in the same plasmid (Figure 2). Plasmids with such gene organization have not been reported previously from any optrA-carrying E. faecalis isolates. While there has been one report of two pheromone-responsive plasmids carrying optrA in E. faecalis (Shang et al., 2019), both plasmids were identified in E. faecalis isolates from pigs, with only one of them (pE508) containing a single sex pheromone gene (prgB) based on full plasmid genome sequencing.

Fourth, our plasmid typing studies demonstrated, for the first time, the abundant presence of rep9-type plasmids (prototype pCF10) in optrA-carrying E. faecalis clinical isolates (17/26, 65%, Table 1), implying a high prevalence of sex pheromone plasmids in clinical isolates. Consistent with this observation, our PCR-based genotyping revealed the presence of three key sex pheromone response genes (prgA, prgB, and prgC) in almost all optrA-carrying E. faecalis clinical isolates (Table 2). It is noteworthy that multiple rep types were detected in 10 E. faecalis isolates which showed a single plasmid in PFGE; this could be explained either by the failure in separating multiple plasmids with similar sizes due to low resolution of the PFGE gel, or by the presence of a hybrid plasmid containing multiple rep types as has been reported previously (Pavlova et al., 2002). It is also noteworthy that a single rep type was detected in two E. faecalis isolates which showed two plasmids with different sizes; this could be explained either by a potential partial degradation of the plasmid in the process of PFGE, or by the presence of two plasmids which contained the same rep gene family and may differ in other coding and/or non-coding regions. Clarification of these possibilities requires further investigation by other approaches particularly the long-read next-generation sequencing.

Fifth, our functional studies with CIA (induced by JH2-2 filtrate) detected different degrees of cell clumping in most of the 23 E. faecalis clinical isolates (17/23, 73.9%) carrying optrA in plasmids, indicating that pheromone-inducible conjugation is operational in these isolates. The absence of clumping in some of these isolates may be caused by the presence of other pheromone receptors different from those for cAD1 and cCF10 or JH2-2 infiltrate used in the CIA assay.

Finally, the hypothesis of sex pheromone-mediated transfer of optrA is further supported by our previous transcriptomics (Hua et al., 2018) and proteomics (Yan et al., 2018) studies of the E. faecalis P10748, which consistently showed that OptrA and several sex pheromone response molecules (PrgA, PrgB, and PrgY) were among the most significantly up-regulated molecules.

The plasmid pEF10748 identified in this study represents a novel plasmid for E. faecalis. In addition to the presence of optrA and multiple sex pheromone response genes described above, this plasmid contains other drug resistance and virulence determinants. The fexA gene, which confers resistance to chloramphenicol and florfenicol, is located closely to the optrA gene in pEF10748. The region containing these two drug resistance genes is flanked by two transposase genes including the IS1216 and ISL3 family transposases (Figure 2). The same gene organization has been reported in only one partially sequenced plasmid (pXY17) from an E. faecalis clinical isolate (He et al., 2016). It is likely that this organization will facilitate the movement of the resistance genes to different locations (plasmids or chromosomes) or different bacteria. This possibility awaits further investigation. In addition to drug resistance genes, CDS45 in plasmid pEF10748 encodes a putative holin-like toxin (Supplementary Table S3), which is known to function through disruption of the host cell membrane (Saier and Reddy, 2015). Whether it performs a similar function in E. faecalis awaits future investigation. Of note, a homolog to the pheromone receptor prgZ/traC was not identified in the plasmid PEF10748 despite rigorous search with different approaches. This absence has also been reported for pheromone-responsive plasmid pE211 in E. faecalis E211 (Shang et al., 2019). It is unknown how this absence affects the transfer of the plasmid pEF10748. We suspect that this absence may reduce the efficiency of plasmid conjugation, given that the transfer frequencies we observed with this plasmid appeared to much lower compared to pheromone-responsive plasmids containing prgZ/traC (Dunny et al., 1982; Lim et al., 2006) and mutant strains lacking PrgZ can still respond to the pheromone (Leonard et al., 1996).

Our finding of the integration of the optrA resistance gene into a pheromone-responsive plasmid may explain, at least partially, the increasing, wide dissemination of linezolid resistance all over the world. According to surveillance of antibiotic resistance in 2019 from, China 63 hospitals in Chongqing (unpublished data), up to 2.1% (60/2871) of E. faecalis clinical isolates have developed resistance to linezolid while no vancomycin resistance (0/2948) was detected. Although there have been reports of successful in vitro transfer of optrA-carrying plasmids from E. faecalis into vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (Wang et al., 2015), there is no report to date of clinical isolates of Enterococcus sp. showing resistance to both linezolid and vancomycin in China. Vancomycin resistance gene has also been found on pheromone-responsive plasmids (Magi et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2009) though the mechanism of how the resistance is regulated by the plasmid remains unclear.

This study clearly has some limitations. The distribution of key sex pheromone response genes in clinical isolates was determined by PCR alone using total genomic DNA, which is unable to distinguish whether these genes are located in plasmids. Clarification of this question requires further studies by DNA hybridization or full plasmid genome sequencing. Despite the availability of a relative large collection of optrA-carrying plasmids, we sequenced only one of them (strain P10748), which was chosen due to our previous studies by transcriptome (Hua et al., 2018) and proteome (Yan et al., 2018) analysis. It is unknown if the remaining plasmids also carry sex pheromone response genes as well as other mobile genetic elements, why some isolates showed a single plasmid but multiple rep types, and why some isolates showed multiple plasmids but a single rep type. We anticipate that continuing decrease in next-generation sequencing cost should allow us to sequence all these plasmids as well as related chromosomes, and provide answers to these questions in the future.

Conclusion

This report represents the largest study of the prevalence and transferability of optrA-carrying plasmids in E. faecalis clinical isolates, and the first identification of a plasmid carrying optrA along with multiple sex pheromone response genes in clinical isolates. Our integrative molecular and phenotypic analysis strongly suggests that optrA-mediated linezolid resistance can be widely disseminated through sex pheromone plasmid transfer. Further studies are needed to determine how this transfer is regulated and what the best strategy to monitor and control the transmission is.

Author’s Note

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at BioRxiv (Zou et al., 2019).

Data Availabilty Statement

The dataset for this study can be found in the GenBank: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MK993385).

Author Contributions

YX designed the study. JZou and ZT collected the data and performed experiments. JY, HL, YC, and JZhao assisted in experiments. DZ, JZhang, and YT analyzed the data. All authors contributed to data drafting, revising, and approved the final submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Xiuli He and Yuhang Liu for their assistance in collection of clinical samples. We also wish to thank Dr. Liang Ma at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland for critical reviewing of the manuscript.

Funding. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81572055).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01185/full#supplementary-material

References

- Antonelli A., D’Andrea M. M., Brenciani A., Galeotti C. L., Morroni G., Pollini S., et al. (2018). Characterization of poxtA, a novel phenicol-oxazolidinone-tetracycline resistance gene from an MRSA of clinical origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 1763–1769. 10.1093/jac/dky088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias C. A., Murray B. E. (2012). The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10 266–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz R. K., Bartels D., Best A. A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R. A., et al. (2008). The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B. M., Harding G. P., Zuccarelli A. J. (1995). A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 226 235–240. 10.1006/abio.1995.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beganovic M., Luther M. K., Rice L. B., Arias C. A., Rybak M. J., LaPlante K. L. (2018). A review of combination antimicrobial therapy for Enterococcus faecalis bloodstream infections and infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67 303–309. 10.1093/cid/ciy064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J. K., Fleige C., Lange D., Klare I., Werner G. (2018). Rapid emergence of highly variable and transferable oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance gene optrA in German Enterococcus spp. clinical isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 52 819–827. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer J., Lomsadze A., Borodovsky M. (2001). GeneMarkS: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 2607–2618. 10.1093/nar/29.12.2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi R., Qin T., Fan W., Ma P., Gu B. (2018). The emerging problem of linezolid-resistant enterococci. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 13 11–19. 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Wang Y., Schwarz S., Lv H., Li Y., Liao K., et al. (2015). Enterococcal isolates carrying the novel oxazolidinone resistance gene optrA from hospitals in Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Henan, China, 2010-2014. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 21 1095.e1091–1095.e1094 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Càmara J., Camoez M., Tubau F., Pujol M., Ayats J., Ardanuy C., et al. (2019). Detection of the novel optrA gene among linezolid-resistant Enterococci in Barcelona. Spain. Microb Drug Resist. 25 87–93. 10.1089/mdr.2018.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco L. M., Bernal J. F., Zankari E., Léon M., Hendriksen R. S., Perez-Gutierrez E., et al. (2017). Detection of linezolid resistance due to the optrA gene in Enterococcus faecalis from poultry meat from the American continent (Colombia). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 678–683. 10.1093/jac/dkw490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell D. B. (2007). Properties of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1, a member of a widely disseminated family of pheromone-responding, conjugative, virulence elements encoding cytolysin. Plasmid 58 205–227. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI K. (2018). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: CLSI Supplement M100, 28th Edn Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande L. M., Castanheira M., Flamm R. K., Mendes R. E. (2018). Evolving oxazolidinone resistance mechanisms in a worldwide collection of enterococcal clinical isolates: results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 2314–2322. 10.1093/jac/dky188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelli G., Paoletti C., Baldassarri L., Guaglianone E., Di Rosa R., Magi G., et al. (2004). Sex pheromone response, clumping, and slime production in enterococcal strains isolated from occluded biliary stents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42 3419–3427. 10.1128/jcm.42.8.3419-3427.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunny G., Yuhasz M., Ehrenfeld E. (1982). Genetic and physiological analysis of conjugation in Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 151 855–859. 10.1128/jb.151.2.855-859.1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghaieb H., Freitas A. R., Abbassi M. S., Novais C., Zouari M., Hassen A., et al. (2019). Dispersal of linezolid-resistant enterococci carrying poxtA or optrA in retail meat and food-producing animals from Tunisia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74 2865–2869. 10.1093/jac/dkz263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan R., Li D., Wang Y., He T., Feßler A. T., Schwarz S., et al. (2016). Presence of the optrA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus sciuri of porcine origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 7200–7205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell D. J., Mendes R. E., Ross J. E., Sader H. S., Jones R. N. (2011). LEADER Program results for 2009: an activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using 6,414 clinical isolates from 56 medical centers in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 3684–3690. 10.1128/AAC.01729-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A. R., Elghaieb H., León-Sampedro R., Abbassi M. S., Novais C., Coque T. M., et al. (2017). Detection of optrA in the African continent (Tunisia) within a mosaic Enterococcus faecalis plasmid from urban wastewaters. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3245–3251. 10.1093/jac/dkx321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawryszewska I., Żabicka D., Hryniewicz W., Sadowy E. (2017). Linezolid-resistant enterococci in Polish hospitals: species, clonality and determinants of linezolid resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36 1279–1286. 10.1007/s10096-017-2934-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Shen Y., Schwarz S., Cai J., Lv Y., Li J., et al. (2016). Genetic environment of the transferable oxazolidinone/phenicol resistance gene optrA in Enterococcus faecalis isolates of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1466–1473. 10.1093/jac/dkw016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt H., Manias D. A., Bryan E. M., Klein J. R., Marklund J. K., Staddon J. H., et al. (2005). Characterization of the pheromone response of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pCF10: complete sequence and comparative analysis of the transcriptional and phenotypic responses of pCF10-containing cells to pheromone induction. J. Bacteriol. 187 1044–1054. 10.1128/jb.187.3.1044-1054.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua R., Xia Y., Wu W., Yan J., Yang M. (2018). Whole transcriptome analysis reveals potential novel mechanisms of low-level linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. Gene 647 143–149. 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua R., Xia Y., Wu W., Yang M., Yan J. (2019). Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of 43 low-level linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis strains in Chongqing. China. Ann. Lab. Med. 39 36–42. 10.3343/alm.2019.39.1.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Chen L., Wu Z., Wang L. (2017). Retrospective analysis of genome sequences revealed the wide dissemination of optrA in Gram-positive bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 614–616. 10.1093/jac/dkw488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. B., Garcia-Migura L., Valenzuela A. J. S., Løhr M., Hasman H., Aarestrup F. M. (2010). A classification system for plasmids from enterococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 80 25–43. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M., Sekizuka T., Matsui H., Suzuki K., Seki H., Saito M., et al. (2018). Complete genome sequence and characterization of linezolid-resistant clinical isolate KUB3006 carrying a cfr(B)-transposon on its chromosome and -plasmid. Front. Microbiol. 9:2576. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach K. L., Brickner S. J., Noe M. C., Miller P. F. (2011). Linezolid, the first oxazolidinone antibacterial agent. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1222 49–54. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05962.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard B. A., Podbielski A., Hedberg P. J., Dunny G. M. (1996). Enterococcus faecalis pheromone binding protein, PrgZ, recruits a chromosomal oligopeptide permease system to import sex pheromone cCF10 for induction of conjugation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 260–264. 10.1073/pnas.93.1.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Wang Y., Schwarz S., Cai J., Fan R., Li J., et al. (2016). Co-location of the oxazolidinone resistance genes optrA and cfr on a multiresistance plasmid from Staphylococcus sciuri. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1474–1478. 10.1093/jac/dkw040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. K., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Ike Y. (2006). Pheromone-responsive conjugative vancomycin resistance plasmids in Enterococcus faecalis isolates from humans and chicken feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 6544–6553. 10.1128/AEM.00749-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magi G., Capretti R., Paoletti C., Pietrella M., Ferrante L., Biavasco F., et al. (2003). Presence of a vanA-carrying pheromone response plasmid (pBRG1) in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 47 1571–1576. 10.1128/aac.47.5.1571-1576.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R. E., Hogan P. A., Jones R. N., Sader H. S., Flamm R. K. (2016). Surveillance for linezolid resistance via the Zyvox§Annual Appraisal of Potency and Spectrum (ZAAPS) programme (2014): evolving resistance mechanisms with stable susceptibility rates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 1860–1865. 10.1093/jac/dkw052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy L. M., Sahm D. F., Gilmore M. (2000). Relationships between enterococcal virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13 513–522. 10.1128/cmr.13.4.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na S. H., Moon D. C., Choi M. J., Oh S. J., Jung D. Y., Kang H. Y., et al. (2019). Detection of oxazolidinone and phenicol resistant enterococcal isolates from duck feces and carcasses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 293 53–59. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen I. T., Banerjei L., Myers G. S. A., Nelson K. E., Seshadri R., Read T. D., et al. (2003). Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299 2071–2074. 10.1126/science.1080613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova S. I., Kiliç A. O., Topisirovic L., Miladinov N., Hatzos C., Tao L. (2002). Characterization of a cryptic plasmid from Lactobacillus fermentum KC5b and its use for constructing a stable Lactobacillus cloning vector. Plasmid 47 182–192. 10.1016/s0147-619x(02)00005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosvoll T. C. S., Pedersen T., Sletvold H., Johnsen P. J., Sollid J. E., Simonsen G. S., et al. (2010). PCR-based plasmid typing in Enterococcus faecium strains reveals widely distributed pRE25-, pRUM-, pIP501- and pHTbeta-related replicons associated with glycopeptide resistance and stabilizing toxin-antitoxin systems. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58 254–268. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said H. S., Abdelmegeed E. S. (2019). Emergence of multidrug resistance and extensive drug resistance among enterococcal clinical isolates in Egypt. Infect. Drug Resist. 12 1113–1125. 10.2147/IDR.S189341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier M. H., Reddy B. L. (2015). Holins in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: multifunctional xenologues with potential biotechnological and biomedical applications. J. Bacteriol. 197 e2046–e2014. 10.1128/JB.02046-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi M., Guérin F., Zouari A., Beyrouthy R., Auzou M., Fines-Guyon M., et al. (2019). Emergence of optrA-mediated linezolid resistance in enterococci from France, 2006-16. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74 1469–1472. 10.1093/jac/dkz097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Werckenthin C., Kehrenberg C. (2000). Identification of a plasmid-borne chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance gene in Staphylococcus sciuri. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 2530–2533. 10.1128/aac.44.9.2530-2533.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Li D., Shan X., Schwarz S., Zhang S. M., Chen Y. X., et al. (2019). Analysis of two pheromone-responsive conjugative multiresistance plasmids carrying the novel mobile optrA locus from Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Drug Resist. 12 2355–2362. 10.2147/IDR.S206295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey L. K. R., Edwards T. A., O’Neill A. J. (2016). ABC-F proteins mediate antibiotic resistance through ribosomal protection. mBio 7:e01975. 10.1128/mBio.01975-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilipounidaki K., Gerontopoulos A., Papagiannitsis C., Petinaki E. (2019). First detection of an optrA-positive, linezolid-resistant ST16 from human in Greece. New Microbes New Infect. 29:100515. 10.1016/j.nmni.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lv Y., Cai J., Schwarz S., Cui L., Hu Z., et al. (2015). A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 2182–2190. 10.1093/jac/dkv116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner G., Willems R. J. L., Hildebrandt B., Klare I., Witte W. (2003). Influence of transferable genetic determinants on the outcome of typing methods commonly used for Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 1499–1506. 10.1128/jcm.41.4.1499-1506.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Xia Y., Yang M., Zou J., Chen Y., Zhang D., et al. (2018). Quantitative proteomics analysis of membrane proteins in with low-level linezolid-resistance. Front. Microbiol. 9:1698. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Wang Y., Wang S., Wang Z., Du X.-D., Jiang H., et al. (2016). Prevalence and abundance of florfenicol and linezolid resistance genes in soils adjacent to swine feedlots. Sci. Rep. 6:32192. 10.1038/srep32192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Tomita H., Inoue T., Ike Y. (2009). Isolation of VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis strains from nosocomial infections: first report of the isolation and identification of the pheromone-responsive plasmids pMG2200, encoding VanB-type vancomycin resistance and a Bac41-type bacteriocin, and pMG2201, encoding erythromycin resistance and cytolysin (Hly/Bac). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 735–747. 10.1128/aac.00754-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Tang Z., Yan J., Liu H., Chen Y., Zhang D., et al. (2019). Dissemination of linezolid-resistance through sex pheromone plasmid transfer in Enterococcs faecalis. bioRxiv. 10.1101/832691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.