Abstract

A third of US students are suspended over a K-12 school career. Suspended youth have worse adult outcomes than non-suspended students, but these outcomes could be due to selection bias: that is, suspended youth may have had worse outcomes even without suspension. This study compares the educational and criminal justice outcomes of 480 youth suspended for the first time with those of 1193 matched non-suspended youth from a nationally representative sample. Prior to suspension, the suspended and non-suspended youth did not differ on 60 pre-suspension variables including students’ self-reported delinquency and risk behaviors, parents’ reports of socioeconomic status, and administrators’ reports of school disciplinary policies. Twelve years after suspension (ages 25–32), suspended youth were less likely than matched non-suspended youth to have earned bachelors degrees or high school diplomas, and were more likely to have been arrested and on probation, suggesting that suspension rather than selection bias explains negative outcomes.

Keywords: delinquency, educational achievement, alienation, school dropout, emerging adulthood/adult transition, discrimination, racism, longitudinal design

School suspension is used widely, affects many students, and begins as early as preschool (Gilliam and Shahar, 2006). Over a K-12 school career, 35% of students are suspended at least once; among Black students, 67% of males and 45% of females are suspended (Shollenberger, 2015). School suspension increased in prevalence beginning with the 1994 federal Gun-Free Schools Act, which mandated that states adopt zero-tolerance policies that punish students who have weapons in school with at least 1-year suspension. Subsequent “zero tolerance” policies at state and local levels mandated suspension for possession of illegal drugs; possession of over-the-counter drugs, including ibuprofen and cough drops; and subjective offenses such as “insubordination” (Skiba & Knesting, 2001). Most suspensions are less than 2 weeks because longer suspensions are subject to stricter legal protections (Arum, 2003).

Substantial evidence about chronic absences and subsequent lower educational attainment and criminal justice involvement (Rumberger, 1995; Rouse, 2007) may suggest that school suspension would lead to lower educational attainment and higher criminal justice involvement, but school suspension has not been studied extensively.

School suspensions aim to obtain better behavior from the punished student and maintain school norms by removing students. Some studies find that suspension accomplishes these aims. Suspension removes disruptive students from schools temporarily (Cook, Gottfredson, & Na, 2010; Kinsler, 2013) and may improve school climate and by reducing peer influences to engage in deviant behavior (Zimmerman, 2014). One study of North Carolina middle school students found that suspended students are more likely to comply with school rules in the school year that they were suspended (Kinsler, 2013).

Other studies have found that suspended students are more likely to engage in antisocial behavior, have involvement with the criminal justice system, and are less likely to complete school in both the short and long-term. Youth are more likely to be arrested both during the month of suspension (Monahan, VanDerhei, Bechtold, & Cauffman, 2014) and within a year of suspension (Hemphill, Toumbourou, Herrenkohl, McMorris, & Catalano, 2006). Within a year of suspension, suspended youth are also more likely to engage in antisocial behavior (Hemphill, Kotevski, Herrenkohl, Smith, Toumbourou, & Catalano, 2013; Hemphill et al., 2006) and use marijuana (Evans-Whipp, Plenty, Catalano, Herrenkohl, & Toumbourou, 2015) and tobacco (Hemphill, Heerde, Herrenkohl, Toumbourou, & Catalano, 2012). In a 13-year national longitudinal survey, youth suspended for at least 10 days were less likely to graduate high school and more likely to be arrested and incarcerated by the end of the study (ages 26–31) (Shollenberger, 2015). In a 7–8 year longitudinal study in Florida, youth suspended in 9th grade were less likely to graduate high school, graduate on time, and enroll in post-secondary education, and more suspensions predicted worse outcomes (Balfanz, Byrnes, & Fox, 2015).

School suspension is characterized by racial disparities, and suspension’s racial disparities may increase educational disparities. The White-Black disparity has declined for achievement but increased for suspensions, especially among secondary students: from 1972 to 2012, the proportion of all students suspended for at least one day increased from 3% to 5% for White students (6% to 7% for secondary students) and from 6% to 16% for Black students (12% to 23% for secondary students) (Losen, Hodson, Morrison, & Belway, 2015; Wald & Losen, 2003). Racial disparities in suspension are problematic in themselves but also predict racial disparities in school completion. One nationally representative study found that much of the widening of the Black-White high school drop-out gap between 1979 and 1997 can be explained by school suspension (Suh, Malchow, & Suh, 2014). Racial disparities in suspension may result from discrimination by teachers and administrators rather than differences in students’ behavior, and students perceive racial disparities in suspension (Ruck & Wortley, 2002). Psychological experiments using vignettes that manipulate a hypothetical student’s race find that teachers punish Black students more harshly than White students for the same infraction (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). Some research attributes racial disparities in school suspension to stricter school suspension policy in a cross-sectional study (Kinsler, 2011) and teacher reports of misbehavior 5–8 years prior to suspension in a nationally representative longitudinal study (Wright, Morgan, Coyne, Beaver, & Barnes, 2014). Teacher reports of misbehavior in early grades may indicate implicit bias that results in subsequent school suspension, which has been found against Black children in preschool (Gilliam, Maupin, Reyes, Accavitti, & Shic, 2016).

The American Psychological Association, American Association of Pediatrics, and American Bar Association have criticized zero tolerance school suspension policies for potentially reducing educational attainment, harming employment prospects, increasing risk behavior, and increasing criminal justice involvement (American Association of Pediatrics Committee on School Health, 2003; Lamont et al., 2013; Reynolds et al., 2008) and for creating injustice through mandatory minimum sentences that do not permit judicial discretion (American Bar Association, 2001). Legal scholars claim that zero tolerance school suspension deprives students of their right to equal access to education (Bitner, 2015). In place of out-of school-suspension, the American Association of Pediatrics recommends Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (Lamont et al., 2013) because initial studies suggest that schools can replace suspension with positive reinforcement and a larger range of consequences for misbehavior (Cook et al., 2010). Cities and states have made isolated attempts to reduce school suspension (Barnhart, Franklin, & Alleman, 2008; DeLorenzo & Rider, 2015). Evidence of the negative impacts of school suspension (Fabelo, Thompson, Plotkin, Carmichael, & Booth, 2011) prompted the federal Supportive School Discipline Initiative in 2011, which promotes alternatives to suspension. Despite these critiques, school suspension continues to be common nationwide (Losen et al., 2015).

Hypotheses

Suspended students may comply with rules in the short term, but suspension may create long-term secondary deviance due to the social ramifications of suspension, such as labeling, stigma, limiting options, or creating separation. These social ramifications result in further deviance that magnifies the impact of the initial deviance. The secondary deviance hypothesis is supported by qualitative evidence that suspended students and their parents/caregivers report feeling more disengaged from school after suspension, and students report that they did not improve their behavior after suspension (Gibson & Haight, 2013; Michail, 2012). Secondary deviance may be more enduring deviance that may not have occurred otherwise, even if the initial deviance were minor, not premeditated, or a one-time experiment (Becker, 1963; Lemert, 1967; Paternoster & Iovanni, 1989). Recent research finds that youth who are arrested or stopped by police are more likely to engage in secondary deviance as a result of labeling (Liberman, Kirk, & Kim, 2014; Wiley, Slocum, & Esbensen, 2013). School suspension may create a similar process, which is supported by studies that describe a “school-to-prison pipeline” beginning with suspension (Nicholson-Crotty, Birchmeier, & Valentine, 2009).

The alternative hypothesis is selection bias: the negative effects observed among suspended youth may be attributable to selection into suspension, rather than the suspension itself. Suspended youth are more likely than non-suspended youth to have poor outcomes even if they were not suspended, due to greater pre-suspension risk-taking and low socioeconomic status. This hypothesis is supported by a longitudinal Australian study that did not find differences in educational attainment two years after suspension and attributed the association between suspension and lower educational attainment in other studies to selection bias (Cobb-Clark, Kassenboehmer, Le, McVicar, & Zhang, 2015) because residual selection bias may remain after statistical adjustment methods such as regression analysis (Berk, 2010; Rubin, 1997.)

This study discriminates between the secondary deviance and selection bias hypotheses using matched sampling on 60 variables and sensitivity analysis. This study compares outcomes 5 and 12 years after a first suspension in 1995–96 with outcomes of comparable youth not suspended in that time interval or before. To clarify temporal ordering of events and avoid bias from unobserved suspension history (Kinsler, 2011), this study is distinctive in focusing on students who had never been suspended at baseline. Including students with previous suspensions would prevent matching on pre-suspension factors because pre-suspension characteristics of these students would be unknown, so such analysis could not exclude the possibility that deviant behavior of previously-suspended students was due to the previous suspension.

Methods

Data

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent and Adult Health (Add Health)1 comprises a nationally representative sample of adolescents attending public and private high schools and their feeder middle schools in 1994–95. Adolescents with disabilities, Blacks with college-educated parents, among other groups, were oversampled at baseline (Tourangeau & Shin, 1999).

The Add Health surveys were given to adolescent respondents in 1995 (wave 1, response rate 79.0%), 1996 (wave 2, 88.6%), 2001 (wave 3, 77.4%), and 2008 (wave 4, 80.3%); their parents (93% female parents) in 1995 (response rate 82.5%); and school administrators in 1995 (response rate 97.7%.) (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 2015)

Respondents were a 9593 person subsample who participated in the first two surveys, at least one of the subsequent surveys (wave 3 and/or 4), and reported at baseline having never received an out-of-school suspension or been expelled from school (“Have you ever received an out-of-school suspension from school?” and “Have you ever been expelled from school?”) Limiting the analyses to never-suspended students avoids bias from unobserved suspension history (Kinsler, 2011), allows the study to observe incident suspensions, and preserves temporal ordering between control variables and suspension.

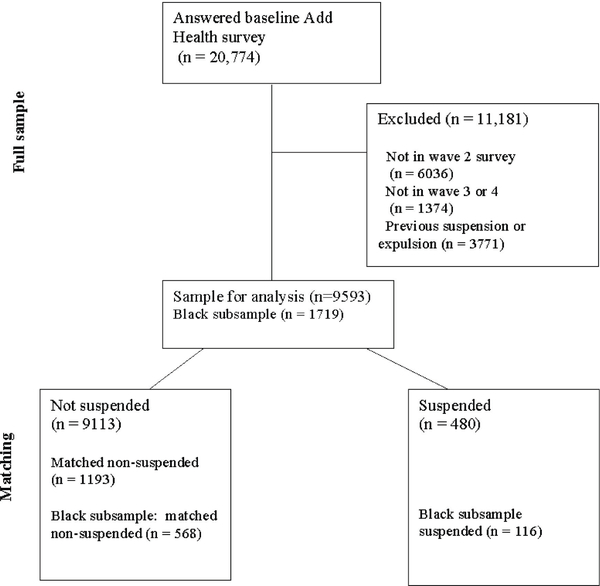

Teachers and administrators may have different criteria in deciding whether to suspend Black youth (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015), so the analysis was repeated in a subsample of 1719 Black youth who were never expelled or suspended from school at baseline. The full sample includes the Black subsample, as well. The sample selection and sample sizes are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Construction of matched sample.

This matched sampling analysis is a limited subsample of the full Add Health data, so the analysis could not use survey weights or yield nationally representative estimates of the incidence of suspension. The Add Health survey weights were developed for the entire sample, based on both probability of selection and probability of response. Using survey weights with a subsample would cause the variance to change in unpredictable ways, so Add Health advises researchers not to use survey weights with sub-samples (Chantala & Tabor, 2010).

Predictor

The predictor of interest is self-reported suspension between 1995 and 1996, based on the wave 2 question, “During this school year (during the 1995–96 school year) did you receive an out-of-school suspension from school?”

Control variables

The control variables were 60 potential confounders of the relationship between suspension and educational/criminal justice outcomes, which were derived from 182 survey items from adolescent self-report, measured height, interviewer’s assessment of the adolescent, parent’s self-report, and administrator’s report about school policy. The confounders include measures of demographics, socioeconomic status, educational achievement, parents’ risk behavior, substance use, personality, delinquency and adverse experiences, appearance, relationship with parent, physical and mental health, and environmental context (complete list in Appendix 1.)

Potential confounders were identified from past research about suspension (Losen et al., 2015; Shollenberger, 2015) and educational attainment (Bowen et al., 2011), arrest (Ou et al., 2007), and the self-control theory of crime (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Wolfe & Hoffmann, 2016.) Add Health data lacks a set of items with clear face validity intended to measure self-control, but past literature includes at least three approaches to measuring self-control using the Add Health data (Beaver, 2011; Perrone, Sullivan, Pratt, & Margaryan, 2004; Wolfe & Hoffmann, 2016.) The analysis in this paper measured self-control using six constructs: personal control (1 item), decision making style (1 item), school attachment (9 items), conscientiousness (5 items), agreeableness (3 items), and parent’s assessment of child (4 items).

The control variables were all measured at baseline, except for father ever in prison, which was not measured until 2001. The 2001 father in prison measurement was used as a control variable because it was not likely to be a consequence of a child’s suspension from school. Single or aggregate variables using a Likert-type scale were normalized to 0–100, except the Add Health CES-D, which had an established cut-off.

Outcomes

Educational attainment and criminal justice outcomes were derived from the statement of the American Association of Pediatrics on school suspension (Lamont et al., 2013). Educational attainment included attainment of a high school diploma (excluding equivalency degree) in 2001 and 2008; bachelor’s degree (BA) in 2001 and 2008; having ever been expelled in 2001; attainment of associates’ degree in 2008 and graduate (post-BA) degree in 2008.

Criminal justice involvement measured in 2001 included having ever been arrested, having been arrested or convicted as a minor, having been arrested or convicted as an adult. Criminal justice involvement measured in 2008 included having been arrested once, having been arrested 2 or more times, having ever been in prison, and having ever been on probation.

Impulsivity was the sum of 9 Likert-scale items on a scale from 0 to 1 (alpha=0.94) measured in 2001 and was used as a negative control: we expect no difference in impulsivity among suspended versus matched non-suspended individuals.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data using the R 3.4.1 and Stata 11.2 statistical packages.

Factor analysis

We used standard factor analysis procedures to derive all multi-item measures, requiring that factor loadings be at least 0.4. To improve the quality of matching, factor analysis decisions avoided the overuse of data reduction.

Bivariate analysis

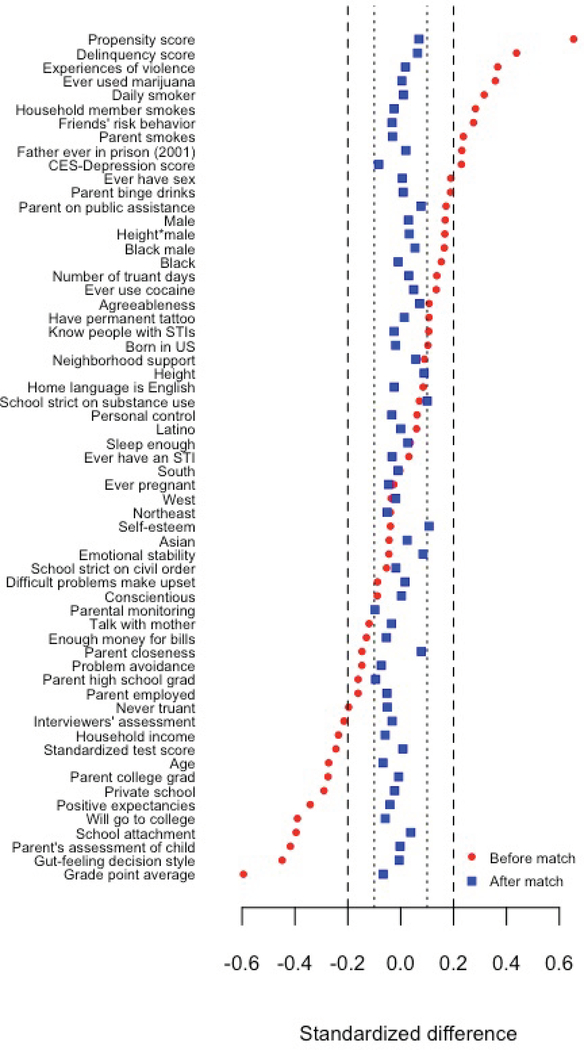

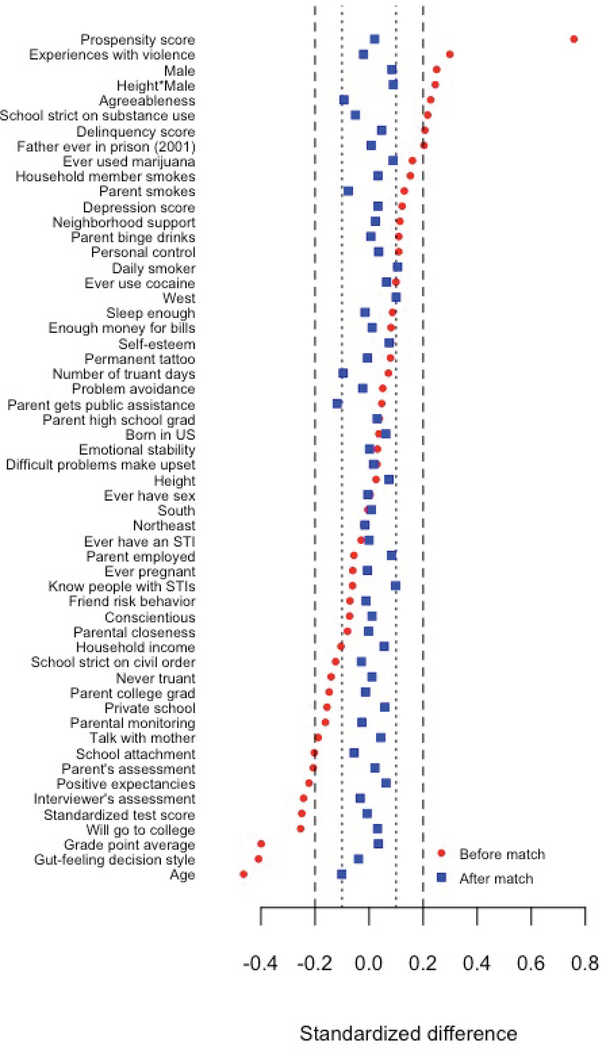

We identified factors where suspended and non-suspended youth differed most using standardized differences, a measure of effect size. Standardized differences are considered insignificant for 0–0.2, small for 0.2–0.5, medium for 0.5–0.8, and large if greater than 0.8. Standardized differences before and after matching were plotted using a Love plot (Love, 2002).

Matched sampling

Matched sampling refers to various statistical methods that create a comparison group of non-suspended youth similar to suspended youth on variables prior to suspension. The specific matched sampling method is selected through trial and error by its ability to construct a similar comparison group, rather than derived according to criteria known in advance (Morgan & Winship, 2015).

Sixty potential confounders of the relationship between school suspension and each outcome were identified using literature review and expert feedback. The matched sampling method that achieved balance was 3:1 exact and nearest-neighbor Mahalanobis matching with replacement, within propensity score calipers of 0.25 standard deviations, using the R MatchIt library (Ho, Imai, King, & Stuart, 2008). Matched sampling achieved balance on 60 variables plus the estimated propensity score in the general sample and 55 variables plus the propensity score in the Black subsample. Propensity score estimates are the fitted values from a logistic regression predicting suspension from pre-suspension factors; the formulation of each propensity score model will be explained below.

In the full sample, 3 non-suspended youth were matched to each suspended youth using the following procedure. For each suspended youth, exact matching reduced the set of eligible non-suspended youth by requiring that only non-suspended youth with the same daily smoking status and ever-marijuana status could be considered. Propensity calipers reduced the set of eligible non-suspended youth further to those within 0.25 standard deviations of the estimated propensity score. Finally, Mahalanobis matching identified the 3 closest youth according to a correlation-adjusted distance measure of age, grade point average, and delinquency scores. Propensity scores were estimated from a logistic regression predicting a first suspension from demographic factors (male gender, age, born in US, Latino, Asian, and Black race/ethnicity, home language is English), socioeconomic factors (mother high school graduate, mother college graduate, parent is currently employed, parent-reported household income, parent-reported enough money to pay bills, father ever in prison [2001]), health and risk behavior factors (experiences with violence, respondent smokes daily, household member smokes, mother smokes, mother binge drinks, respondent smokes daily, depression score, positive expectancies, respondent sleeps “enough”), educational factors (standardized test score, school attachment, expect to attend college, attend private vs. public school, school is strict on civil order), and personality factors (parent’s assessment of their child, agreeableness, emotional stability, parental closeness, systematic vs. gut-feeling decision making).

The literature suggests that Black youth are suspended disproportionately, particularly for subjective offenses such as insubordination, so the assignment mechanism for Black youth is likely to be different. This analysis includes a separate matched sampling model for the subsample of Black youth. This subsample will have reduced power due to lower sample size, so any significant relationships are particularly noteworthy.

In the Black subsample, 8 non-suspended youth were matched to each suspended youth on age and grade point average. The propensity scores were estimated from a logistic regression predicting a first suspension from demographic factors (male gender, born in US), socioeconomic factors (parent-reported enough money to pay bills, father ever in prison [2001]), health and risk behavior factors (household member smokes, positive expectancies, overweight status, delinquency score, ever used marijuana), and educational factors (school administrator’s reported disciplinary policies are strict on substance use and strict on civil order, never truant from school, standardized test score, expect to attend college, attend private vs. public school).

Analysis within matched sample

After matching, the analysis estimated the relative risks of each outcome with a multivariate Poisson working model with robust standard errors within the matched sample, using the weights obtained from the matched sampling procedure. A Poisson model allows coefficients to be interpreted as relative risks, which are more easily interpreted than odds ratios from a logistic regression model and less subject to bias away from the null (Austin & Laupacis, 2011; McNutt, Wu, Xue, & Hafner, 2003; Zou, 2004).

Sensitivity analysis

Matched sampling balanced the groups on 60 variables, plus propensity score, but results could be confounded by an unobserved variable that is orthogonal to the 60 observed variables. We estimated the maximum sensitivity parameter gamma that makes the difference between treated and matched control individuals significant at the 0.05 level using the sensitivitymw package for R (Rosenbaum, 2014; Rosenbaum, 2015).

Results

Among 9593 youth without prior expulsion or suspension, 480 were suspended and 54 were expelled for the first time between 1995 and 1996. The one-year incidence of first suspension was 4.5% among non-Hispanic whites, 5.8% among non-black Hispanics, and 6.7% among Blacks, a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared p=0.0005, Pearson chi-squared p=0.004.) For first expulsion, the one-year incidence was 0.3% among non-Hispanic whites, 0.6% among non-Black Hispanics, and 1.3% among Blacks, a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis and Pearson chi-squared p < 0.0001.) The model matched 1193 never-suspended youth to the suspended youth, 30 of whom (2.5%) had weights over 2. The matching model balanced on 60 variables plus the estimated propensity score (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Comparison of standardized differences of baseline factors before and after matching, comparing students suspended for the first time in 1995–96 with students who had never been suspended as of 1996.

Among 1719 Black youth never suspended or expelled at baseline, 116 were suspended and 23 were expelled between 1995 and 1996. The model matched 568 never-suspended Black youth to the suspended Black youth, 33 of whom (5.3%) had weights over 2. The matching model balanced on 56 variables including the propensity score (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Comparison of standardized differences of baseline factors before and after matching, comparing Black students who were suspended for the first time in 1995–96 with students who had never been expelled or suspended as of 1996.

Factors predicting suspension

The factors most strongly associated with suspension included lower grade-point averages, a gut-feeling decision style, parent’s low assessment of their child, lower school attachment, lower expectations of college attendance, lower positive expectancies, more daily smoking, more likely to have ever smoked marijuana, more experiences with violence, and higher delinquency scores (Figure 2). After matching, suspended and never-suspended youth had similar values of all 60 factors plus the propensity score (Figure 2).

Among Black youth, the factors most strongly associated with suspension were younger age, gut-feeling decision style, lower grade-point averages, and more experiences with violence (Figure 3). Factors that predict suspension among Blacks but not the general population include higher agreeableness, strict school substance use policy, and being a tall male. Among suspended Blacks, 40% attended schools with strict substance use policies versus 29% of those who were not suspended (standardized difference=0.22). After matching, suspended and never-suspended youth were similar on all 55 factors plus the propensity score (Figure 3.)

Outcomes five years after first suspension

Comparing outcomes five years after suspension, in 2001, youth suspended for the first time between 1995 and 1996 were 8% less likely to earn a high school diploma than similar youth who had never been suspended by 1996 (non-suspended youth) and 2.7 times as likely to have been expelled (Table 1). Among Black youth, suspended youth were 94% less likely to have earned a BA than similar youth who had never been suspended by 1996, and 2.8 times as likely to have been expelled.

Table 1:

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for outcomes in 2001 and 2008 associated with a first suspension between 1995 and 1996, adjusted for control variables.

| All students (n=1673) | Black students (n=684) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | RR | 95% CI | P | Gamma | % | RR (95% CI) | P | Gamma | ||

| Outcome in 2001 (dichotomous) | ||||||||||

| Ever expelled | 5.1 | 2.69 | [1.70, 4.26] | <0.001 | 1.8 | 6.4 | 2.77 | [1.44, 5.32] | 0.002 | 2.1 |

| High school diploma | 68.2 | 0.92 | [0.86, 0.99] | 0.03 | 1.05 | 71.7 | 0.93 | [0.81, 1.07] | ||

| BA | 3.6 | 0.78 | [0.40, 1.55] | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.06 | [0.005, 0.80] | 0.03 | 1.15 | |

| Ever arrested | 10.3 | 1.40 | [1.05, 1.89] | 0.02 | 1.1 | 7.1 | 1.38 | [0.62, 3.08] | ||

| Arrested as a minor | 4.1 | 1.94 | [1.15, 3.19] | 0.01 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 2.90 | [1.04, 8.07] | 0.04 | |

| Convicted as a minor | 1.6 | 3.75 | [1.60, 8.79] | 0.002 | 1.75 | 0.8 | 2.81 | [0.60, 13.3] | ||

| Arrested as adult | 7.9 | 1.31 | [0.79, 1.61] | 5.1 | 0.47 | [0.16, 1.38] | ||||

| Convicted as adult | 3.9 | 1.22 | [0.73, 2.05] | 2.5 | 1.45 | [0.32, 6.64] | ||||

| Outcome in 2008 (dichotomous) | ||||||||||

| Arrested 1+ times | 28.2 | 1.38 | [1.18, 1.60] | <0.001 | 1.35 | 23.4 | 1.39 | [1.02, 1.87] | 0.03 | 1.4 |

| Arrested once | 15.5 | 1.30 | [1.01, 1.66] | 0.04 | 1.05 | 13.3 | 1.58 | [0.97, 2.59] | 0.07 | 1.3 |

| Arrested 2+ times | 13.7 | 1.51 | [1.17, 1.95] | 0.002 | 1.3 | 11.8 | 1.15 | [0.66, 1.98] | ||

| Ever in prison | 16.3 | 1.23 | [0.97, 1.56] | 0.09 | 1.1 | 15.8 | 1.75 | [1.11, 2.75] | 0.02 | 1.1 |

| Ever on probation | 14.0 | 1.49 | [1.15, 1.92] | 0.003 | 1.35 | 12.9 | 2.06 | [1.25, 3.41] | 0.005 | 1.25 |

| High school diploma | 74.8 | 0.94 | [0.88, 1.00] | 0.05 | 1.0 | 76.9 | 0.91 | [0.83, 1.00] | 0.05 | |

| AA | 11.2 | 1.04 | [0.75, 1.44] | 8.9 | 0.87 | [0.42, 1.82] | ||||

| BA | 16.3 | 0.76 | [0.59, 0.97] | 0.03 | 1.1 | 19.7 | 0.93 | [0.63, 1.39] | ||

| Graduate degree | 3.5 | 0.88 | [0.48, 1.61] | 4.5 | 1.04 | [0.46, 2.37] | ||||

Each entry is derived from a regression coefficient within the respective matched samples, of all students and Black students, controlling for demographics, socioeconomic status, educational achievement, parents’ risk behaviors, substance use, personality, delinquency and adverse experiences, appearance, relationship with parent, physical and mental health, and neighborhood context. Dichotomous outcomes are from a Poisson working model and continuous outcomes are from a linear regression. P-values are listed if P ≤ 0.1.

Suspended youth were 40% more likely to have been arrested, 94% more likely to have been arrested as a minor, and 3.8 times as likely to have been convicted as a minor than similar non-suspended youth.

Suspended youth did not differ in impulsivity in 2001 (negative control) from matched non-suspended youth in both unadjusted or adjusted models: on average, suspended youth were 0.009 points more impulsive than matched non-suspended youths in multivariate linear regression (p=0.54).

Outcomes 12 years after first suspension

Comparing outcomes 12 years after suspension, in 2008, youth suspended for the first time between 1995 and 1996 were 6% less likely to have earned a high school diploma and 24% less likely to have earned a BA than similar non-suspended youth.

Suspended youth were 30% more likely to have been arrested once, 51% more likely to have been arrested two or more times, 23% more likely to have been in prison, and 49% more likely to have been on probation than similar non-suspended youth. Among Black youth, suspended youth were 58% more likely to have been arrested once than similar non-suspended Black youth.

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis of outcomes 5 years after suspension suggests that expulsion is insensitive to an unobserved factor that causes an 80% increase in suspension, and conviction as minor is insensitive to a factor that causes a 75% increase in suspension (Table 1.)

The sensitivity analysis of outcomes 12 years after suspension suggests that 1+ arrests and probation are insensitive to an unobserved factor that causes a 35% increase in suspension, and 2+ arrests is insensitive to a factor that causes a 30% increase in suspension.

Outcomes 5 and 12 years after any suspension

We conducted matched sampling among all participants in Add Health including those with prior suspensions (n=12797). Previous suspension predicts subsequent suspension: 61% of suspended youth had a previous suspension versus 21% of non-suspended youth. Matched sampling balanced participants on the above 60 variables, prior suspension, and the estimated propensity score (Appendix 3.) Analysis of this matched sample (n=3680) did not alter the conclusions substantially. Suspended youth were less likely to have a high school diploma or BA, and more likely to be expelled, arrested, convicted, and to have been imprisoned or on probation (Appendix 3).

Discussion

Suspended youth had lower educational attainment and worse criminal justice outcomes than non-suspended youth who were matched on 60 pre-suspension characteristics. The greater likelihood of assigning suspension to Blacks, and the different factors that predict assignment into suspension, such as greater chances of suspension for tall Black males, concurs with findings of racial discrimination in psychology experiments (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). Suspension removes youth from school to impose a short-term, minor sanction on youth and to create a more orderly school temporarily, but this temporary removal seems to create long-term consequences for suspended youth that cannot be explained by selection into suspension.

These results are consistent with the secondary deviance hypothesis that suspension for initial deviance results in additional deviance. After suspension, students may be labeled as “deviant” or “troublemakers” by school faculty, staff, peers, and themselves. These labels may reduce students’ inhibitions to engage in further deviance because they may feel that others expect them to be deviant. Students who have positive influences at school are separated from those positive influences by suspension (Michie, 2001). During suspension, suspended youth may meet and socialize with more deviant peers, and begin to engage in further deviant behavior as a result of these peers. School suspension may function similarly to stops and arrest in labeling youth as deviant so that the youth are likely to engage in further deviance (Liberman et al., 2014; Wiley et al., 2013).

Greater delinquency and lower grades predict greater chances of suspension in both the full sample (which is 17.9% Black) and the Black subsample. However, Black youth have unique risk factors for school suspension, suggesting racial discrimination in students’ assignment to suspension (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015). Tall male youth are more likely to be suspended, which could be due to racial discrimination. Strict school substance use policies predicted greater risk of suspension in the Black sub-sample but not the general population. The uniformity of strict suspension policies is thought to reduce subjectivity, but strict policies appear to magnify racial disparities in practice.

Black youth also seem to have worse outcomes from school suspension, which could be explained by a greater secondary deviance effect. Suspended Black youth may correctly perceive that their suspensions are related to racial bias rather than their behavior, so they may be more likely to engage in secondary deviance because they perceive that the educational system is racially biased (Ruck & Wortley, 2002; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015).

Suspended youth are substantially more likely to become involved with the criminal justice system, consistent with claims that suspension facilitates the school-to-prison pipeline (Nicholson-Crotty et al., 2009). Suspension is an important concern for policy makers concerned about the growth of mass incarceration, especially of minorities. Current discussions focus on police-youth interactions, but these suspension findings suggest that police-youth interactions may be shaped by earlier school-youth interactions and could be improved with positive school discipline policies.

These effects are consistent with the two studies of long-term effects of suspension, but the magnitudes are smaller, perhaps due to matching reducing residual confounding. Balfanz and colleagues found that the likelihood of drop-out increased with the number of suspensions in 9th grade, ranging from 32% for one suspension to 53% for 4 or more suspensions; each suspension reduced the odds of high school graduation by 20% and reduced the odds of post-secondary enrollment by 12% in logistic regressions controlling for attendance, demographics, and grades in administrative data in Florida (n=181,897) (Balfanz et al., 2015). Shollenberger found that suspended White boys are 23 percentage points less likely to have a high school diploma, 31 percentage points less likely to have attended any college, 29 percentage points less likely to have a BA, and 38 percentage points more likely to have ever been arrested, with similar gaps for Black and Hispanic boys, in her analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1997 (Shollenberger, 2015).

Strengths and Limitations

Matched sampling minimizes potential confounding on the matched pre-suspension factors and factors correlated with them. Matched non-suspended youth are similar to the suspended youth on 60 variables derived from 182 survey items about students’ delinquency and health risk behaviors, parents’ reports about socioeconomic status, interviewers’ reports about respondents’ appearance, and administrators’ reports of school disciplinary policies. Both matching and regression yield associative rather than causal inference, but matching yields more valid results for 3 reasons. First, regression models rely on dubious parametric assumptions about linear or log-linear relationships between variables. Regression models cannot adjust for large differences between affected groups, even on average. Suspended youth differ from non-suspended youth in grades, delinquency, and school attachment, so matched sampling is particularly appropriate for studying school suspension. Second, in contrast with traditional regression methods, this matched sampling model computed outcome differences only after verification that the matched suspended group is similar to the non-suspended group. This separation ensures that the model is selected independently of the study’s results; with regression, it is impossible to verify model correctness without seeing the results. Third, matching allows adjustment for more variables than does regression: in this case, matching balanced on 60 factors, including composite variables, based on 182 survey items.

This study included a sensitivity analysis because matching adjusts for unobserved characteristics only to the extent that they are associated with the observed characteristics (Rosenbaum, 2002.) Residual confounding may remain after matching because factors not correlated with the 60 factors that were balanced on could partially explain outcome differences between suspended and non-suspended youth. However, it is difficult to identify a specific unobserved characteristic unrelated to the 60 matched factors that explains the observed associations. For example, skin color is unmeasured, and youth with darker skin of any race or ethnicity may be more likely both to be suspended and to have lower educational attainment and higher arrest likelihoods in adult life due to colorism (Landor et al., 2013; Sweet, McDade, Kiefe, & Liu, 2007). However, the pervasive effects of colorism implies that skin color is likely related to variables that were balanced on, such as interviewer perception and grade averages.

Any study with multiple outcomes risks false significance due to multiple comparisons. This study reported all investigated educational attainment and criminal justice involvement outcomes. Further, regressions were only performed a single time after matching to ensure that the matching model was selected independently of the study’s results, as in a randomized experiment (Rubin, 1997.)

These data came from a nationally representative survey, but results are not nationally representative because they exclude youth with prior suspensions or expulsions: for example, the incidence of first suspension in this subsample is lower than suspension incidence in national data. Limiting the sample improves internal validity by preserving the temporal ordering between the pre-suspension control variables and the first suspension, but it reduces external validity.

This study may underestimate the negative impacts of school suspension for three reasons. First, suspension and expulsion are self-reported. Students may misclassify long suspensions as expulsions, resulting in under-estimates of the effects of suspensions by excluding the longest suspensions, which would likely have the largest effects on students’ outcomes. Second, Add Health over-sampled Black youth with college-educated parents. College-educated parents have more authoritative parenting styles and more resources to help youth (Dornbusch, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987). Suspended youth in this sample may have better outcomes after suspension than suspended youth in the general Black population, so this study may underestimate the effects of suspension for Black youth. Third, suspensions in this study occurred in 8th-12th grades, but youth suspended during earlier grades may have larger effects from suspension and begin the process of school disengagement earlier.

Conclusions

Consistent with the secondary deviance hypothesis, adults suspended as youth have lower educational attainment and greater criminal justice involvement than a matched non-suspended group. Administrators may not perceive short-term negative impacts from suspension, but suspension may initiate social processes with long-term implications for individuals and society. Evidence-based positive discipline approaches may avoid this negative cycle.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Constantine Frangakis, Fran Goldscheider, Sandra Hofferth, Clea McNeely, Stephen Raudenbush, James Rosenbaum, and anonymous reviewers for helpful conversations. This research was funded by the Spencer Foundation (grant #201000138), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041 (Maryland Population Research Center), and the SUNY Downstate School of Public Health. The funding sources did not have any role in any aspect of the study design, implementation, writing, or manuscript submission.

Abbreviations:

- GED

general equivalency degree

- BA

bachelor of arts or other 4-year college degree

- AA

associate of arts or other 2-year college degree

Appendix 1: Description of control variables

The control variables were 60 potential confounders of the relationship between suspension and educational/criminal justice outcomes that may be associated with both suspension and the educational and criminal justice outcomes, which were derived from 182 survey items. The 60 control variables have been organized into the following categories for ease of reading, but these categories do not have statistical implications: demographics, socioeconomic status, educational achievement, parents’ risk behavior, substance use, personality, delinquency and adverse experiences, appearance, relationship with parent, physical and mental health, and environmental context.

Demographics comprises 11 variables from 7 items: gender, male-black interaction term, age, Latino ethnicity, Asian and Black race, nativity, whether the respondent’s primary home language is English, and region of country.

Socioeconomic status (SES) predicts likelihood of suspension, educational attainment, and criminal justice outcomes; it includes 6 variables from 5 items: parent is high school grad, college grad, parent-reported household income (log scale), parent-reported enough money to pay bills, parent receives public assistance, and parent is currently employed.

Educational achievement is associated with school engagement and predicts educational attainment and could predict school suspension; it includes 9 variables from 36 items: standardized test score (Add Health Peabody Vocabulary Test), expectations to attend college, whether the respondent attends a private school, grade point average (average of 4 self-reported grades, alpha=0.72), school is strict on substance use (top quartile of administrator-reported school discipline policy for alcohol, drugs, and smoking, 8 items, alpha=0.97), school is strict on civil order (top quartile of administrative-reported school discipline policy for offenses such as stealing school property and verbally abusing a teacher, 7 items, alpha=0.73), positive expectations for the future (aggregate variable of 5 items such as will not be killed by age 21, will live to age 35, alpha=0.61), and school attachment (aggregate variable of 9 items including feeling safe at school, problems with teachers, problems completing homework, alpha=0.78).

Substance use could lead to both suspension and lower educational attainment and greater chances of arrest, and includes 4 variables from 6 items: lifetime marijuana use, lifetime cocaine use, regular smoking status, and friends’ substance use (number of friends who drink alcohol monthly, use marijuana monthly, smoke daily, 3 items, alpha=0.72).

Youth with parents who engage in risk behavior may have lower educational attainment and greater likelihood of risk behavior that could lead to suspension. The parents’ risk behavior category includes 4 variables from 4 items: parent-reported parent smoking, household member smokes, binge drinking, and one item from 2001: whether the respondent’s father was ever in prison.

Personality predicts both deviance and others’ response to an individual’s deviant behavior. Personality includes 8 variables from 28 items: self-esteem (aggregate of 11 factors modified from Rosenberg’s scale, alpha=0.88), conscientiousness (aggregate of 5 items describing systematic approach to solving problems, alpha=0.78), systematic versus gut-feeling decision-making was measured by the Likert item, “When making decisions, you usually go with your ‘gut feeling’ without thinking too much about the consequences of each alternative.” where higher means more systematic decision-making style, emotional stability (aggregate of 6 items including have a lot of good qualities, a lot to be proud of, alpha=0.87) (Young & Beaujean, 2011), agreeableness (sum of 3 items: never argue with anyone, never get sad, never criticize other people, alpha=0.63), personal control was measured by the Likert-scale item “When you get what you want, its usually because you worked hard for it.”, problem avoidance was measured by the Likert-scale items “You usually go out of your way to avoid having to deal with problems in your life.”, and “Difficult problems make you very upset.”.

Delinquency and experiences with violence predict both likelihood of suspension and the outcomes. The delinquency and experiences with violence category includes 4 variables from 24 items: delinquency was the sum of 15 binary items including running away, hurting someone so badly that they needed medical care, participating in a group fight, lying to parents, and stealing <$50 and ≥$50 (alpha=0.80); experiences with violence was the sum of 8 binary variables, such as saw shooting, was shot, shot another (alpha=0.75.); number of truant days in past year; and never truant in the past year.

Students’ appearance may influence how authority figures respond to them and thus affect both likelihood of suspension and criminal justice outcomes. Appearance includes 4 variables from 6 items: having a permanent tattoo, height, height-male interaction term, and the interviewer’s assessment of student’s appearance (attractive, personality attractive, well-groomed, 3 items, alpha=0.74).

Relationship with parent includes 4 variables from 29 items: parent’s assessment of relationship with child (how is child’s life going, get along with child, trust child, child doesn’t have a bad temper, 4 items, alpha=0.67), parental closeness (aggregate of 14 items such as perceived love and warmth, satisfaction with relationship, alpha=0.81), talk with mother (talk with mother about social, personal, school issues, 4 items, alpha=0.62), parental monitoring (parents let respondent make own decisions about weekday bedtime, weekend curfew, how much TV, 7 items, alpha=0.70).

The physical and mental health category includes 6 factors from 33 items: modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression screen score (19 items, alpha=0.86), ever have any of 10 sexually transmitted infections (STI), having ever been pregnant, having ever had sexual intercourse, sufficient sleep, and number of people they know who have had an STI.

Environmental context included 1 factor from 4 items: neighborhood support (e.g., know most of the people in the neighborhood, average of 4 binary items, alpha=0.72).

Appendix 2: Comparison of baseline factors before and after matching.

Table 2a:

Comparison of standardized differences of baseline factors before and after matching, comparing students who were suspended for the first time between 1995 and 1996 with students who had never been suspended as of 1996.

| Pre-matching | Post-matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susp. | Not susp. | Std. diff | Susp. | Not susp. | Std. diff | |

| N | 480 | 9113 | 480 | 1193 | ||

| Grade point average | 2.6 | 3.0 | −0.59 | 2.6 | 2.6 | −0.07 |

| Systematic (vs. gut-feeling) decision style | 41.3 | 53.5 | −0.45 | 41.3 | 41.5 | −0.01 |

| Parent’s assessment of child | 74.3 | 80.7 | −0.42 | 74.3 | 74.3 | 0.00 |

| School attachment | 67.2 | 73.4 | −0.40 | 67.2 | 66.6 | 0.04 |

| Will go to college | 71.7 | 83.4 | −0.39 | 71.7 | 73.5 | −0.06 |

| Positive expectancies | 81.2 | 86.2 | −0.34 | 81.2 | 81.8 | −0.04 |

| Private school | 3.3 | 8.5 | −0.29 | 3.3 | 3.8 | −0.02 |

| Parent college grad | 15.0 | 24.8 | −0.28 | 15.0 | 15.3 | −0.01 |

| Age (years) | 14.8 | 15.2 | −0.27 | 14.8 | 14.9 | −0.07 |

| Standardized test score | 75.5 | 78.0 | −0.25 | 75.5 | 75.5 | 0.01 |

| Household income ($1k) | 31.7 | 37.8 | −0.24 | 31.7 | 33.2 | −0.06 |

| Never truant | 71.5 | 80.4 | −0.20 | 71.5 | 73.8 | −0.05 |

| Parent employed | 59.0 | 66.9 | −0.16 | 59.0 | 61.5 | −0.05 |

| Parent high school grad | 67.9 | 75.4 | −0.16 | 67.9 | 72.4 | −0.10 |

| Problem avoidance | 42.8 | 46.5 | −0.15 | 42.8 | 44.6 | −0.07 |

| Parent closeness | 77.7 | 79.7 | −0.15 | 77.7 | 76.6 | 0.08 |

| Enough money for bills | 66.2 | 72.4 | −0.13 | 66.2 | 68.8 | −0.05 |

| Talk with mother | 45.9 | 49.6 | −0.12 | 45.9 | 47.0 | −0.03 |

| Parental monitoring | 68.7 | 71.1 | −0.10 | 68.7 | 71.1 | −0.10 |

| Conscientiousness | 68.8 | 70.2 | −0.09 | 68.8 | 68.7 | 0.00 |

| Difficult problems make upset | 34.9 | 37.0 | −0.09 | 34.9 | 34.5 | 0.02 |

| School strict on civil order | 22.9 | 25.2 | −0.05 | 22.9 | 23.7 | −0.02 |

| Emotional stability | 77.6 | 78.3 | −0.04 | 77.6 | 76.4 | 0.08 |

| Asian | 7.1 | 8.2 | −0.04 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 0.02 |

| Self-esteem | 76.1 | 76.6 | −0.04 | 76.1 | 74.7 | 0.11 |

| Northeast | 12.9 | 14.2 | −0.04 | 12.9 | 14.7 | −0.05 |

| West | 21.2 | 22.7 | −0.04 | 21.2 | 22.0 | −0.02 |

| Ever pregnant | 1.9 | 2.2 | −0.03 | 1.9 | 2.5 | −0.05 |

| South | 35.6 | 35.8 | 0.00 | 35.6 | 36.1 | −0.01 |

| Ever have sexually transmitted infection | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 1.7 | 2.1 | −0.03 |

| Sleep enough | 74.6 | 73.0 | 0.04 | 74.6 | 73.4 | 0.03 |

| Latino | 17.9 | 15.6 | 0.06 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 0.00 |

| Personal control | 28.4 | 27.0 | 0.06 | 28.4 | 29.1 | −0.03 |

| School strict on substance use | 24.4 | 21.3 | 0.07 | 24.4 | 20.1 | 0.10 |

| Home language is English | 91.2 | 88.9 | 0.08 | 91.2 | 91.9 | −0.02 |

| Height (inches) | 66.0 | 65.6 | 0.09 | 66.0 | 65.6 | 0.09 |

| Neighborhood support | 79.6 | 77.3 | 0.09 | 79.6 | 78.1 | 0.06 |

| Born in US | 74.4 | 69.9 | 0.10 | 74.4 | 75.2 | −0.02 |

| Know people with STIs | 26.5 | 21.8 | 0.11 | 26.5 | 27.6 | −0.03 |

| Have permanent tattoo | 4.4 | 2.2 | 0.11 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 0.01 |

| Agreeableness | 38.3 | 36.2 | 0.11 | 38.3 | 36.9 | 0.07 |

| Ever use cocaine | 5.4 | 2.4 | 0.13 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 0.05 |

| Num. truant days | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.14 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.03 |

| Black | 24.2 | 17.6 | 0.15 | 24.2 | 24.6 | −0.01 |

| Black male | 10.6 | 5.5 | 0.16 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 0.05 |

| Height*male | 30.4 | 24.8 | 0.17 | 30.4 | 29.3 | 0.03 |

| Male | 44.8 | 36.4 | 0.17 | 44.8 | 43.3 | 0.03 |

| Parent on public assistance | 12.1 | 6.5 | 0.17 | 12.1 | 9.6 | 0.08 |

| Parent binge drinks | 16.9 | 9.8 | 0.19 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 0.01 |

| Ever have sex | 34.2 | 25.2 | 0.19 | 34.2 | 33.9 | 0.01 |

| Depression score | 12.7 | 11.1 | 0.23 | 12.7 | 13.2 | −0.08 |

| Father ever in prison (2001) | 19.2 | 10.2 | 0.23 | 19.2 | 18.4 | 0.02 |

| Parent smokes | 32.7 | 21.6 | 0.24 | 32.7 | 34.2 | −0.03 |

| Friends’ risk behavior | 46.9 | 36.0 | 0.28 | 46.9 | 48.2 | −0.02 |

| Household member smokes | 49.4 | 35.2 | 0.28 | 49.4 | 50.6 | −0.02 |

| Daily smoker | 33.1 | 18.2 | 0.32 | 33.1 | 32.6 | 0.01 |

| Ever use marijuana | 36.2 | 19.0 | 0.36 | 36.2 | 36.0 | 0.00 |

| Experiences of violence | 7.7 | 3.9 | 0.37 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 0.06 |

| Delinquency score | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.44 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.07 |

| Propensity score | 10.6 | 4.7 | 0.61 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 0.07 |

Table 2b:

Comparison of standardized differences of baseline factors before and after matching, comparing Black students who were suspended for the first time between 1995 and 1996 with students who had never been suspended as of 1996.

| Pre-matching | Post-matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susp. | Not susp. | Std. diff | Susp. | Not susp. | Std. diff | |

| N | 116 | 1603 | 116 | 568 | ||

| Age | 14.5 | 15.1 | −0.46 | 14.5 | 14.6 | −0.10 |

| Systematic (vs. gut-feeling) decision style | 42.2 | 53.5 | −0.41 | 42.2 | 43.3 | −0.04 |

| Grade point average | 2.6 | 2.8 | −0.40 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0.03 |

| Will go to college | 77.9 | 85.5 | −0.25 | 77.9 | 77.0 | 0.03 |

| Standardized test score | 71.8 | 74.3 | −0.25 | 71.8 | 71.9 | −0.01 |

| Interviewer’s assessment | 42.0 | 51.7 | −0.24 | 42.0 | 43.3 | −0.03 |

| Positive expectancies | 82.5 | 86.0 | −0.22 | 82.5 | 81.5 | 0.06 |

| Parent’s assessment | 78.3 | 81.2 | −0.21 | 78.3 | 78.0 | 0.02 |

| School attachment | 69.7 | 72.9 | −0.20 | 69.7 | 70.6 | −0.06 |

| Talk with mother | 45.3 | 51.0 | −0.19 | 45.3 | 43.9 | 0.04 |

| Parental monitoring | 65.5 | 70.0 | −0.16 | 65.5 | 66.3 | −0.03 |

| Private school | 4.3 | 7.5 | −0.16 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 0.06 |

| Parent college grad | 20.7 | 26.7 | −0.15 | 20.7 | 21.2 | −0.01 |

| Never truant | 79.3 | 85.0 | −0.14 | 79.3 | 78.9 | 0.01 |

| School strict on civil order | 28.4 | 34.1 | −0.12 | 28.4 | 29.7 | −0.03 |

| Household income ($1k) | 28.0 | 30.3 | −0.10 | 28.0 | 26.8 | 0.06 |

| Parental closeness | 78.4 | 79.4 | −0.08 | 78.4 | 78.4 | 0.00 |

| Conscientiousness | 72.1 | 73.2 | −0.07 | 72.1 | 71.9 | 0.01 |

| Friends’ risk behaviors | 27.6 | 29.8 | −0.07 | 27.6 | 27.9 | −0.01 |

| Know people with STIs | 30.2 | 33.0 | −0.06 | 30.2 | 25.6 | 0.10 |

| Ever pregnant | 3.4 | 4.6 | −0.06 | 3.4 | 3.6 | −0.01 |

| Parent employed | 63.8 | 66.5 | −0.06 | 63.8 | 59.8 | 0.08 |

| Ever have sexually transmitted infection | 2.6 | 3.1 | −0.03 | 2.6 | 3.3 | −0.05 |

| Northeast | 8.6 | 9.2 | −0.02 | 8.6 | 9.1 | −0.02 |

| South | 56.0 | 56.3 | 0.00 | 56.0 | 55.6 | 0.01 |

| Ever have sex | 37.9 | 37.7 | 0.00 | 37.9 | 38.1 | 0.00 |

| Height (inches) | 65.8 | 65.7 | 0.03 | 65.8 | 65.5 | 0.07 |

| Difficult problems make upset | 35.5 | 34.8 | 0.03 | 35.5 | 35.1 | 0.01 |

| Emotional stability | 81.8 | 81.4 | 0.03 | 81.8 | 81.8 | 0.00 |

| Born in US | 75.0 | 73.4 | 0.04 | 75.0 | 72.3 | 0.06 |

| Parent high school grad | 75.0 | 73.4 | 0.04 | 75.0 | 73.7 | 0.03 |

| Parent gets public assistance | 12.9 | 11.4 | 0.05 | 12.9 | 16.9 | −0.12 |

| Problem avoidance | 42.2 | 40.9 | 0.05 | 42.2 | 42.8 | −0.02 |

| Num. truant days | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.8 | 1.0 | −0.10 |

| Enough money for bills | 64.7 | 60.8 | 0.08 | 64.7 | 64.1 | 0.01 |

| Sleep enough | 75.0 | 71.2 | 0.09 | 75.0 | 75.6 | −0.01 |

| West | 18.1 | 14.3 | 0.10 | 18.1 | 14.2 | 0.10 |

| Ever use cocaine | 3.4 | 1.6 | 0.10 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 0.06 |

| Daily smoker | 11.2 | 7.9 | 0.10 | 11.2 | 7.9 | 0.11 |

| Personal control | 28.5 | 26.1 | 0.11 | 28.5 | 27.7 | 0.04 |

| Parent binge drinks | 12.9 | 9.2 | 0.11 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 0.01 |

| Neighborhood support | 81.7 | 78.9 | 0.11 | 81.7 | 81.1 | 0.02 |

| Depression score | 12.4 | 11.6 | 0.12 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 0.03 |

| Parent smokes | 25.0 | 19.3 | 0.13 | 25.0 | 28.3 | −0.08 |

| Household member smokes | 38.8 | 31.3 | 0.15 | 38.8 | 37.2 | 0.03 |

| Ever use marijuana | 23.3 | 16.5 | 0.16 | 23.3 | 19.5 | 0.09 |

| Father ever in prison (2001) | 21.6 | 13.2 | 0.20 | 21.6 | 21.2 | 0.01 |

| Delinquency score | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.21 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.05 |

| School strict on substance use | 39.7 | 29.0 | 0.22 | 39.7 | 42.1 | −0.05 |

| Agreeableness | 40.2 | 35.4 | 0.23 | 40.2 | 42.2 | −0.09 |

| Height*male | 29.7 | 21.4 | 0.24 | 29.7 | 26.7 | 0.09 |

| Male | 44.0 | 31.5 | 0.25 | 44.0 | 39.8 | 0.08 |

| Experiences with violence | 8.1 | 5.1 | 0.30 | 8.1 | 8.3 | −0.02 |

| Propensity score | 14.6 | 6.2 | 0.76 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 0.02 |

Appendix 3: Examining outcomes among youth who were ever suspended

The main analysis used the framework of a cohort study by examining outcomes after an incident suspension at wave 2 among those who had never been suspended at baseline. This analysis keeps participants with prior suspension in the sample.

Before matching, there were 1220 respondents who were suspended at wave 2, and 11,577 respondents who had never been suspended. We used 3:1 exact and nearest-neighbor matching within propensity score calipers with replacement. The exact matching variables were prior suspension, daily smoking status, and lifetime marijuana use; the Mahalanobis matching were age, grade average, and delinquency score; and the propensity score included 32 variables.

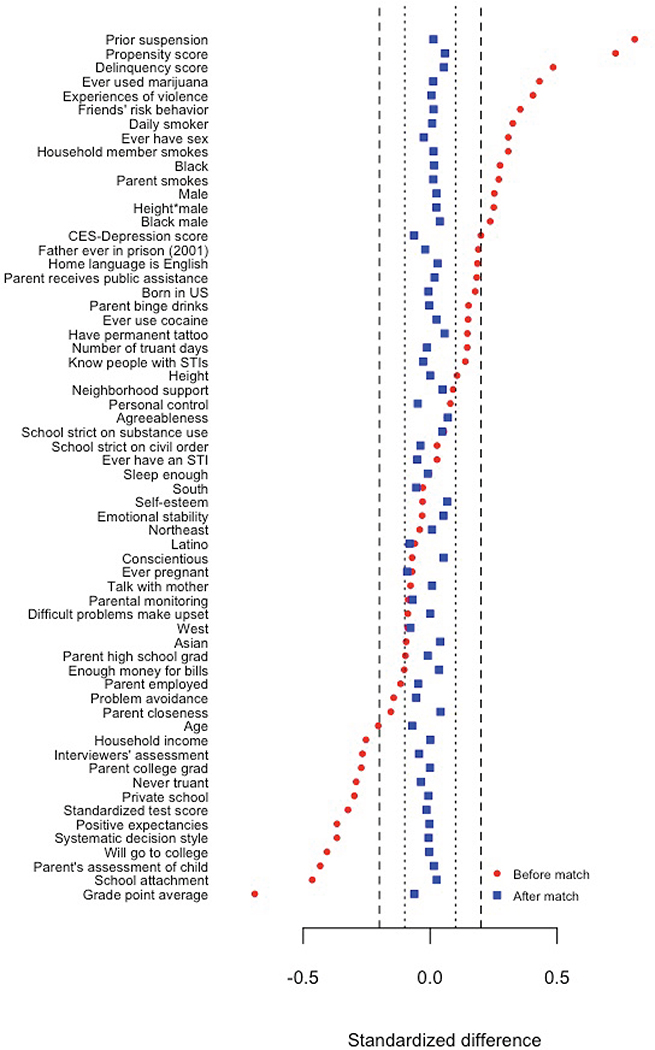

Matching preserved all 1220 suspended respondents and identified a comparison group of 2460 non-suspended respondents. Prior suspension was much more common among suspended than non-suspended respondents: before matching, 61% of suspended respondents had a prior suspension versus 21% of non-suspended respondents. After matching, 60% of non-suspended respondents had a prior suspension. Balance on the remaining variables is shown in Figure A3.

Figure A3:

Comparison of standardized differences of baseline factors before and after matching, comparing students who were suspended in 1995–96 (n=1220 before and after matching) with students who were not suspended in 1995–96 (n=11577 before matching and 2460 after matching), including students with prior suspensions.

Table:

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for outcomes in 2001 and 2008 associated with suspension in 1995–96 in the matched sample (n=3680), adjusted for control variables.

| All students (n=3680) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | RR | 95% CI | P | |

| Outcome in 2001 (dichotomous) | ||||

| Ever expelled | 10.3 | 1.66 | [1.36, 2.03] | <0.001 |

| High school diploma | 61.7 | 0.92 | [0.87, 0.98] | 0.006 |

| BA | 3.3 | 0.69 | [0.43, 1.11] | 0.12 |

| Ever arrested | 13.8 | 1.27 | [1.08, 1.50] | 0.005 |

| Arrested as a minor | 6.4 | 1.23 | [0.95, 1.59] | 0.11 |

| Convicted as a minor | 3.1 | 1.20 | [0.82, 1.75] | 0.36 |

| Arrested as adult | 10.3 | 1.28 | [1.05, 1.57] | 0.02 |

| Convicted as adult | 6.3 | 1.42 | [1.09, 1.86] | 0.009 |

| Outcome in 2008 (dichotomous) | ||||

| Arrested once | 16.6 | 1.26 | [1.08, 1.48] | 0.004 |

| Arrested 2+ times | 20.6 | 1.21 | [1.07, 1.37] | 0.003 |

| Ever in prison | 22.6 | 1.20 | [1.06, 1.35] | 0.003 |

| Ever on probation | 19.2 | 1.28 | [1.13, 1.47] | <0.001 |

| High school diploma | 65.7 | 0.90 | [0.85, 0.95] | <0.001 |

| AA | 9.0 | 0.88 | [0.70, 1.13] | 0.34 |

| BA | 12.7 | 0.70 | [0.57, 0.86] | 0.001 |

| Graduate degree | 3.04 | 0.64 | [0.40, 1.03] | 0.06 |

Footnotes

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

References

- ABA (2001). Zero tolerance policy report. American Bar Association Juvenile Justice Committee. Retrieved from http://www.americanbar.org/groups/child_law/tools_to_use/attorneys/school_disciplinezerotolerancepolicies.html

- Arum R (2003). Judging school discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC & Laupacis A (2011). A tutorial on methods to estimating clinically and policy-meaningful measures of treatment effects in prospective observational studies: A review. International Journal of Biostatistics, 7(1), Article 6. DOI: 10.2202/1557-4679.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfanz R, Byrnes V, & Fox J (2015). “Sent home and put off track: The antecedents, disproportionalities, and consequences of being suspended in 9th grade” In: Losen DJ (Ed.) Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 17–30.) New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart MK, Franklin NJ, & Alleman JR (2008). Lessons learned and strategies used in reducing the frequency of out-of-school suspensions. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 21(2), 75–83. Retrieved from http://www.casecec.org/documents/jsel/jsel_21.2_sep2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM (2011). The Effects of Genetics, the Environment, and Low Self-Control on Perceived Maternal and Paternal Socialization: Results from a Longitudinal Sample of Twins. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 27(1), 85–105. DOI: 10.1007/s10940-010-9100-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker H (1963). Outsiders: Studies of the Sociology of Deviance. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berk R (2010). What You Can and Can’t Properly Do with Regression. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26(4), 481–487. DOI: 10.1007/s10940-010-9116-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner RK (2015). Exiled from Education: Plyler V. Doe’s Impact on the Constitutionality of Long-Term Suspensions and Expulsions. Virginia Law Review, 101(3), 763–805. Retrieved from: http://www.virginialawreview.org/sites/virginialawreview.org/files/Bitner_Book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WG, Chingos MM, & McPherson MS (2011). Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chantala K & Tabor J (2010). Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC; Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/documentation/guides/weight1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cobb-Clark DA, Kassenboehmer SC, Le T, McVicar D, & Zhang R (2015). Is there an educational penalty for being suspended from school? Education Economics, 23(4), 376–395. DOI: 10.1080/09645292.2014.980398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ, Gottfredson DC, & Na C (2010). School Crime Control and Prevention. Crime and Justice, 39(1), 313–440. DOI: 10.1086/652387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo JP & Rider R (2015). Field advisory: Suspension and expulsion of preschool children Office of Special Education and Office of Student Support Services, Albany, NY; Retrieved from http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/publications/2015-memos/preschool-suspensions-expulsions-memo-july-2015.html [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, Roberts DF, & Fraleigh MJ (1987). The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance. Child Development, 58(5), 1244–57. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8624.ep8591146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Whipp TJ, Plenty SM, Catalano RF, Herrenkohl TI, & Toumbourou JW (2015). Longitudinal effects of school drug policies on student marijuana use in Washington State and Victoria, Australia. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 994–1000. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabelo T, Thompson MD, Plotkin M, Carmichael D III, M. P. M., & Booth EA (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide study on how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. Center for State Governments Justice Policy Center. Retrieved from https://csgjusticecenter.org/youth/breaking-schools-rules-report/ [Google Scholar]

- Garson J (2010). Overview of fourteen Southern states’ school suspension laws. Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University. Retrieved from https://childandfamilypolicy.duke.edu/pdfs/familyimpact/2010/Other_States_Suspension_Policies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gibson PA & Haight W (2013). Caregivers’ Moral Narratives of Their African American Children’s Out-of-School Suspensions: Implications for Effective Family-School Collaborations. Social Work, 58(3), 263–272. DOI: 10.1093/sw/swt017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS & Shahar G (2006). Preschool and child care expulsion and suspension: Rates and predictors in one state. Infants and Young Children, 19(3), 228–245. Retrieved from https://medicine.yale.edu/childstudy/zigler/publications/Gilliam%20and%20Shahar%20-%202006%20Preschool%20and%20Child%20Care%20Expulsion%20and%20Suspension-%20Rates%20and%20Predictors%20in%20One%20State_251491_5379.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti M, & Shic F (2016). Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions? Yale University Child Study Center. September 28, 2016 Retrieved from: http://ziglercenter.yale.edu/publications/Preschool%20Implicit%20Bias%20Policy%20Brief_final_9_26_276766_5379.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR & Hirschi T (1990). A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Heerde JA, Herrenkohl TI, Toumbourou JW, & Catalano RF (2012). The Impact of School Suspension on Student Tobacco Use: A Longitudinal Study in Victoria, Australia, and Washington State, United States. Health Education & Behavior, 39(1), 45–56. DOI: 10.1177/1090198111406724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Herrenkohl TI, Smith R, Toumbourou JW, & Catalano RF (2013). Does school suspension affect subsequent youth non-violent antisocial behaviour? A longitudinal study of students in Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(4), 236–249. DOI: 10.1111/ajpy.12026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Toumbourou JW, Herrenkohl TI, McMorris BJ, & Catalano RF (2006). The effect of school suspensions and arrests on subsequent adolescent antisocial behavior in Australia and the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 736–744. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D, Imai K, King G, & Stuart E (2008). Matchit: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference, software version 2.4–21. Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences; Cambridge, MA: Retrieved from https://gking.harvard.edu/MatchIt [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler J (2011). Understanding the black–white school discipline gap. Economics of Education Review, 30(6):1370–1383. DOI: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler J (2013). School Discipline: A Source or Salve for the Racial Achievement Gap? International Economic Review, 54(1):355–383. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2354.2012.00736.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont JH, Devore CD, Allison M, Ancona R, Barnett SE, Gunther R, Holmes B, Lamont JH, Minier M, Okamoto JK, Wheeler LSM, & Young T (2013). Out-of-School Suspension and Expulsion. Pediatrics, 131(3):e1000–e1007. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-3932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landor AM, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Bryant CM, Gibbons FX, Granberg EM, & Melby JN (2013). Exploring the impact of skin tone on family dynamics and race-related outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(5), 817–826. DOI: 10.1037/a0033883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemert E (1967). Human Deviance, Social Problems and Social Control. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman AM, Kirk DS, & Kim K (2014). Labeling Effects of First Juvenile Arrests: Secondary Deviance and Secondary Sanctioning. Criminology, 52(3), 345–370. DOI: 10.1111/1745-9125.12039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Losen D, Hodson C II, M. A. K., Morrison K, & Belway S (2015). Are we closing the school discipline gap? Center for Civil Rights Remedies, UCLA Civil Rights Project. Retrieved from https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/federal-reports/are-we-closing-the-school-discipline-gap

- Love TE (2002). Displaying Covariate Balance after Adjustment for Selection Bias. Paper presented in the Section on Health Policy Statistics, Joint Statistical Meetings, August 11, 2002, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez S (2009). A System Gone Berserk: How Are Zero-Tolerance Policies Really Affecting Schools? Preventing School Failure, 53(3), 153–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00674.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt L, Wu C, Xue X, & Hafner JP (2003). Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(10), 940–943. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michail S (2012). “...becouse Suspension Dosent Teatch You Anything” [sic]: What Students with Challenging Behaviours Say about School Suspension. Report 1324–9320, Australian Association for Research in Education. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542295.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Michie Gregory. (2001), “Ground Zero” In: William Ayers, Bernadine Dohen, and Rick Ayers (Eds.) Zero Tolerance: Resisting the Drive for Punishment in our Schools, New York: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan K, VanDerhei S, Bechtold J, & Cauffman E (2014). From the School Yard to the Squad Car: School Discipline, Truancy, and Arrest. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 43(7), 1110–1122. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-014-0103-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SL & Winship C (2015). Counterfactuals and causal inference: Methods and principles for social research. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson-Crotty S, Birchmeier Z, & Valentine D (2009). Exploring the Impact of School Discipline on Racial Disproportion in the Juvenile Justice System. Social Science Quarterly, 90(4):1003–1018. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00674.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (2015). FAQ: Questions about field work. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/aboutfieldwork

- American Association of Pediatrics Committee on School Health (2003). Policy statement: Out-of-school suspension and expulsion. Pediatrics, 112:1206–1209.Retrieved from: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/112/5/1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua JA & Eberhardt JL (2015). Two Strikes Race and the Disciplining of Young Students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624.DOI: 10.1177/0956797615570365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou S, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ, & Kohler KM (2007). Alterable Predictors of Educational Attainment, Income, and Crime: Findings from an Inner-City Cohort. Social Service Review, 81(1), 85–128.DOI: 10.1086/510783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R & Iovanni L (1989). The labeling perspective and delinquency: An elaboration of the theory and an assessment of the evidence. Justice Quarterly, 6(3), 359–394. DOI: 10.1080/07418828900090261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone D, Sullivan CJ, Pratt TC, & Margaryan S (2004). Parental efficacy, self-control, and delinquency: A test of a general theory of crime on a nationally representative sample of youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48(3), 298–312. DOI: 10.1177/0306624X03262513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C, Skiba R, Graham S, Sheras P, Conoley J, & Garcia-Vazquez E (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.9.852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW & DelVecchio WF (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126(1), 3–25. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR (2002). Observational Studies. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2nd edition. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR (2014). Weighted M-statistics with superior design Sensitivity in Matched Observational Studies With Multiple Controls, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 109:507, 1145–1158, DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2013.879261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR (2015). sensitivitymw: Sensitivity analysis using weighted M-statistics, software version 1.1. Retrieved from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sensitivitymw [Google Scholar]

- Rouse C (2007). “Consequences for the labor market” In Belfield CR & Levin HM (Eds.), The price we pay: Economic and social consequences of inadequate education (pp. 99–124). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D (1997). Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127(8 Pt 2), 757–763. DOI: 0.7326/0003-4819-127-8_Part_2-199710151-00064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD & Wortley S (2002). Racial and Ethnic Minority High School Students’ Perceptions of School Disciplinary Practices: A Look at Some Canadian Findings. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 31(3), 185–195. DOI: 10.1023/A:1015081102189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger R (1995). “Dropping out of Middle School: A Multilevel Analysis of Students and Schools.” American Educational Research Journal, 32(3): 583–625. DOI: 10.2307/1163325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shollenberger TL (2015). Racial Disparities in school suspension and subsequent outcomes: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, In: Losen DJ [Ed.] Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 31–43). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, Peterson R, & Williams T (1997). Office referrals and suspension: Disciplinary intervention in middle schools. Education and Treatment of Children, 20(3), 295–315. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42900491 [Google Scholar]

- Suh S, Malchow A, & Suh J (2014). Why did the black-white dropout gap widen in the 2000s? Educational Research Quarterly, 37(4), 19–40. Retrieved from http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/99990267/why-did-black-white-dropout-gap-widen-2000s [Google Scholar]

- Sweet E, McDade TW, Kiefe CI, & Liu K (2007). Relationships between skin color, income, and blood pressure among African Americans in the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health, 97(12), 2253–2259. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R & Shin H (1999). National longitudinal study of adolescent health: grand sample weight. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC; Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/documentation/guides/weights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wald J & Losen DJ (2003). Defining and redirecting a school-to-prison pipeline. New Directions for Youth Development, 99, 9–15. DOI: 10.1002/yd.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SA, Slocum LA, & Esbensen FA (2013). The Unintended Consequences of Being Stopped or Arrested: An Exploration of the Labeling Mechanisms Through Which Police Contact Leads to Subsequent Delinquency. Criminology, 51(4), 927–966. DOI: 10.1111/1745-9125.12024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe SE & Hoffmann JP (2016). On the measurement of low self-control in Add Health and NLSY79. Psychology, Crime, and Law. 22(7), 619–650. DOI: 10.1080/1068316X.2016.1168428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JP, Morgan MA, Coyne MA, Beaver KM, & Barnes J (2014). Prior problem behavior accounts for the racial gap in school suspensions. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42:257–266. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young JK & Beaujean AA (2011). Measuring Personality in Wave I of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Frontiers in Psychology, 2 DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman SD (2014). The Returns to College Admission for Academically Marginal Students. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(4), 711–754. DOI: 10.1086/676661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G (2004). A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(7), 702–706. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]