Abstract

Aim

Pneumonia is a major cause of death in patients with schizophrenia. Preventive strategies based on identifying the risk factors are needed to reduce pneumonia‐related mortality. This study aimed to clarify the risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical files of consecutive patients with schizophrenia admitted to Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital during a four‐year period from January 2014 to December 2017. We analyzed the clinical differences between patients with and without pneumonia.

Results

Of the 2209 patients enrolled, 101 (4.6%) received the diagnosis of pneumonia at the time of hospital admission while 2108 (95.4%) did not have pneumonia. Multivariable analysis to determine the risk factors related to pneumonia showed that the use of atypical antipsychotics had the highest odds ratio among the predictive factors (2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0‐17.7; P = 0.046), followed by a total chlorpromazine equivalent dose ≥600 mg (2.6; 95% CI 1.7‐4.0; P < 0.001), body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 (2.3; 95% CI 1.6‐3.6; P < 0.001), smoking history (2.0; 95% CI 1.3‐3.1; P < 0.001), and age ≥50 years (1.7; 95% CI 1.2‐2.6; P = 0.002).

Conclusions

We found that advanced age, underweight, smoking habit, use of atypical antipsychotics, and large doses of antipsychotics were risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. Among these factors, it was unclear whether the use of antipsychotics was a direct cause of pneumonia due to is uncertain because our retrospective study design. However, our result might be a good basis of further study focused on reducing pneumonia‐related fatalities in schizophrenic patients with pneumonia.

Keywords: antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, pneumonia, schizophrenia, typical antipsychotics

We found that the advanced age, underweight, smoking habit, and the dose and category of antipsychotics were related to the development of pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. Preventive strategies for reducing pneumonia should be elaborated with careful consideration of these risk factors.

1. INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is the most common, chronic, and disabling of the major mental illnesses.1 Patients with schizophrenia have a higher mortality rate than the general population.2 Suicide occurs at a higher frequency in this group. At the same time, they also have a higher risk of physical illness and poorer treatment outcomes.3 Previous studies have reported that the high risk of physical illness and poor treatment outcomes in patients with schizophrenia were associated with specific behaviors and perceptions such as (a) lack of proper health care, (b) less access to physical healthcare resources, and (c) increased risk of complications.4, 5

One of the major causes of death in patients with schizophrenia is pneumonia.6 Pneumonia accounts for about half of all deaths in psychiatric hospitals7, 8 and has a higher incidence among patients with schizophrenia than the general population. Patients with schizophrenia had a higher incidence of pneumonia (odds ratio = 1.77) in Taiwan.9 The risk of pneumococcal disease in patients with schizophrenia was also high in England (odds ratio = 2.3).10 Preventive strategies based on modifiable risk factors are important to reduce pneumonia‐related mortality.

The risk factors for pneumonia in the general population have been well‐studied. Koviula et al. reported that advanced age, alcoholism, and comorbidities were independent risk factors for pneumonia.11 Farr et al12 added the importance of cigarette smoking. Almirall et al13 found that underweight and previous pneumonia history were significant risk factors. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the risk factors for pneumonia among patients with schizophrenia.

Although our hospital is a psychiatric hospital, we have a Medical Comorbidity Ward and have treated patients with both schizophrenia and pneumonia.14 We therefore performed a retrospective cohort study to elucidate the risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

The clinical files of consecutive patients with schizophrenia who were admitted to Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital during a four‐year period from January 2014 to December 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. If patients were admitted more than once during the study period, the data from their first hospitalization were used. Patients whose period of hospitalization was no more than a couple of days were excluded because their diagnosis of schizophrenia was deemed to be less reliable, and the clinical information regarding the patient was also deemed to be inadequate. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was made by psychiatric physicians in accordance with the ICD‐10 criteria.15 This study was approved by the institutional review board of Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital, and written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design. Patient anonymity was preserved.

We examined each patient's physical characteristics and clinical parameters on admission. The database developed here included the type and dose of the prescribed antipsychotics. For the latter, we used the chlorpromazine equivalent dose table developed by Toru, which is the most commonly used conversion chart in Japan.16 In addition, the physical characteristics and clinical parameters were compared between the two patient groups with and without pneumonia on admission in order to detect the risk factors for pneumonia. At Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital, all patients are asked to undergo a chest X‐ray on admission. Internal medicine physicians diagnosed pneumonia based on clinical symptoms suggestive of pneumonia (cough, fever, productive sputum, dyspnea, chest pain, or abnormal breath sounds), and pneumonic infiltration detected by chest X‐ray. A multivariate analysis determined which risk factors were related to pneumonia.

2.2. Statistical analyses

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between patients with and without pneumonia were analyzed using the chi‐squared test for categorical variables and Student's t test for quantitative variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the role of several variables as risk factors related to pneumonia. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. The following variables with P < 0.05 in univariate logistic regression were included in multivariate analysis as dependent variables: use of typical and atypical antipsychotics, large dose of antipsychotics, underweight, smoking history, and advanced age. A statistical software package (JMP, version 10.0.2; SAS Institute; Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

3. RESULTS

A clinical chart of 4253 admissions and 2974 patients with schizophrenia during the study period was reviewed. Of the 2974 patients, 2209 patients were included in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design

The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The characteristics of the patients with pneumonia differed distinctly from those of patients without pneumonia. The pneumonia group tended to be older (52.3 ± 12.0 vs 47.2 ± 12.1 years, P = 0.002) and have a smoking history (66.3 vs 49.2%, P < 0.001) and lower body mass index (BMI) (19.9 ± 4.1 vs 21.7 ± 4.3 kg/m2, P < 0.001) than the patients without pneumonia.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 2209 patients with schizophrenia complicated by pneumoniaa

| With pneumonia (n = 101) | Without pneumonia (n = 2108) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 52.3 ± 12.0 | 47.2 ± 12.1 | 0.002 |

| Males/females, n | 55/46 | 1188/920 | 0.70 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | |||

| Current/former smoker | 67 (66.3%) | 1037 (49.2%) | <0.001 |

| Never smoker | 34 (33.7%) | 1071 (50.8%) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Neoplastic disease | 1 (1.0%) | 40 (1.9%) | 0.50 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (3.0%) | 38 (1.8%) | 0.40 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (5.0%) | 46 (2.2%) | 0.07 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 3 (3.0%) | 37 (1.8%) | 0.37 |

| Chronic renal disease | 5 (5.0%) | 77 (3.7%) | 0.50 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (4.0%) | 98 (4.6%) | 0.75 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (8.9%) | 198 (9.4%) | 0.87 |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Height, cm | 165.5 ± 7.6 | 165.1 ± 7.6 | 0.61 |

| Body weight, kg | 54.2 ± 10.4 | 58.8 ± 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 19.9 ± 4.1 | 21.7 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Typical antipsychotics, n (%) | 10 (9.9%) | 507 (24.1%) | 0.001 |

| Chlorpromazine | 1 (1.0%) | 58 (2.8%) | 0.28 |

| Levomepromazine | 5 (5.0%) | 228 (10.8%) | 0.06 |

| Haloperidol | 5 (5.0%) | 223 (10.6%) | 0.07 |

| Others | 1 (1.0%) | 53 (2.5%) | 0.33 |

| Atypical antipsychotics, n (%) | 97 (96.0%) | 1890 (89.7%) | 0.04 |

| Risperidone | 38 (37.6%) | 661 (31.4%) | 0.19 |

| Olanzapine | 23 (22.8%) | 580 (27.5%) | 0.30 |

| Quetiapine | 18 (17.8%) | 425 (20.2%) | 0.57 |

| Clozapine | 1 (1.0%) | 33 (1.6%) | 0.65 |

| Aripiprazole | 15 (14.9%) | 213 (10.1%) | 0.13 |

| Others | 28 (27.7%) | 716 (34.0%) | 0.19 |

| Total chlorpromazine equivalent dose, mg | 692.0 ± 336.0 | 517.5 ± 269.2 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

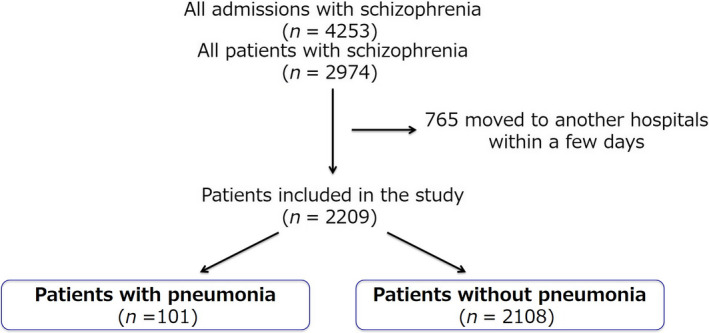

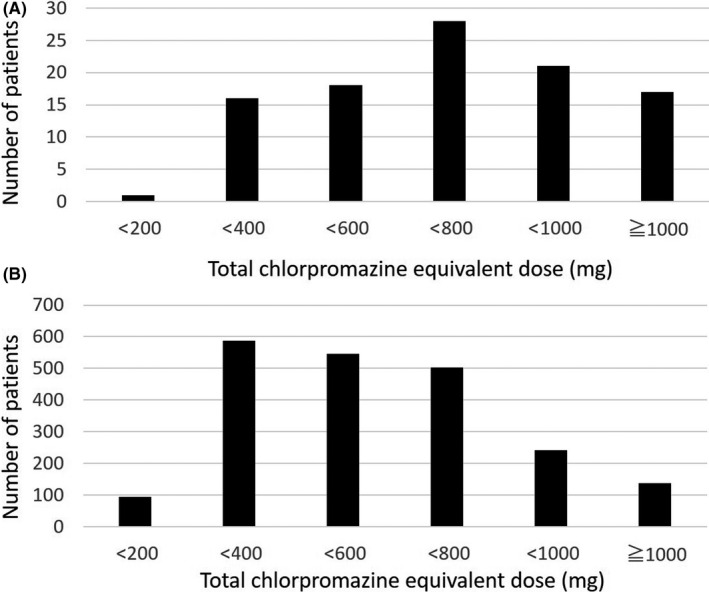

The prescribed antipsychotics differed significantly between the patients with and without pneumonia (Table 1). Typical antipsychotics were prescribed less frequently and atypical antipsychotics were prescribed more frequently to patients with pneumonia than to those without pneumonia. The total chlorpromazine equivalent dose was significantly higher for the patients with pneumonia than for those without pneumonia (692.0 ± 336.0 vs 517.5 ± 269.2 mg, P < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the distribution of the patients according to the total chlorpromazine equivalent dose. The proportion of patients with pneumonia is shown in Figure 3. The increased risk of pneumonia was dose‐dependently observed.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patients with schizophrenia according to total chlorpromazine equivalent dose. The patients were divided into groups with (A) or without (B) pneumonia

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients with pneumonia according to total chlorpromazine equivalent dose. The risk of pneumonia increased dose‐dependently. The proportion of patients with pneumonia was calculated by dividing the number of patients with pneumonia by the total number of patients

To identify the risk factors related to pneumonia, we performed multivariate analysis (Table 2). Use of atypical antipsychotics had the highest odds ratio among the predictive factors (2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0‐17.7; P = 0.046), followed by large dose of antipsychotics (2.6; 95% CI 1.7‐4.0; P < 0.001), underweight (2.3; 95% CI 1.6‐3.6; P < 0.001), smoking history (2.0; 95% CI 1.3‐3.1; P < 0.001), and advanced age (1.7; 95% CI 1.2‐2.6; P = 0.01).

Table 2.

Risk factors for pneumonia identified by multivariate analysis

| Risk factors | Regression coefficient | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 | 4.165 | 2.3 | 1.6‐3.6 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥50 years | 2.645 | 1.7 | 1.2‐2.6 | 0.01 |

| Smoking history | 3.314 | 2.0 | 1.3‐3.1 | 0.001 |

| Use of atypical antipsychotics | 1.996 | 2.7 | 1.0‐17.7 | 0.046 |

| Use of typical antipsychotics | −3.140 | 0.35 | 0.18‐0.67 | 0.002 |

| Total chlorpromazine equivalent dose ≥600 mg | 4.518 | 2.6 | 1.7‐4.0 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

4. DISCUSSION

We identified significant risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia, which were advanced age, underweight, smoking habit, and administration of a higher chlorpromazine equivalent dose or atypical antipsychotics. While this study corroborates the findings of previous studies on the risk factors for pneumonia in the general population, it also provides more established evidence of factors associated with the occurrence of pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. This knowledge will provide the means of identifying groups that are at risk for pneumonia and require preventive intervention.

Advanced age seems to be related to the development of pneumonia. This may be the result of a general weakening of the immune system, efficacy of vaccines, mucosal barrier function, and cough reflex.17, 18 Our study revealed that advanced age was an independent risk factor for pneumonia. Aged patients with schizophrenia in particular should be carefully observed for the development of pneumonia.

Nutrition has a close relationship with susceptibility to infection. Malnutrition by itself increases the host's susceptibility to infectious diseases, and these infections, in turn, have negative repercussions on the metabolism of the host, worsening the host's nutritional state.19 BMI is widely used as an index of an individual's nutritional status.20 Several studies have revealed that underweight is associated with the risk of pneumonia.13, 21 Underweight is prevalent in Japanese patients with schizophrenia. Sugai et al22 reported that Japanese patients with schizophrenia showed a higher prevalence of underweight than the general Japanese population (13.8% vs 7.9%). In the present study, the prevalence of underweight in patients with schizophrenia was consistent with the findings of previous studies (patients with pneumonia: 41.6%; patients without pneumonia: 23%). Because underweight is a potentially treatable condition, nutritional intervention for underweight patients with schizophrenia deserves serious consideration.

An increase in the risk of pneumonia was found to be associated with smoking status in the present study. Smoking is a well‐known and important risk factor for pneumonia among the general population. There is consistent evidence to show that smoking itself increases respiratory infections in smokers. Invasive pneumococcal disease was associated with cigarette smoking (OR = 4.1) in a case‐control study.23 Smoking is highly prevalent among patients with schizophrenia, but these patients are less likely to be treated than patients without schizophrenia.24 Despite the concern that smoking cessation may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, the current evidence does not support this assumption.25 Smoking cessation should be taken into account as a means of preventing pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia.

The use of antipsychotics has been suggested as a possible risk factor for pneumonia. Several observational studies were conducted to explore the association between the use of antipsychotics and pneumonia in a cohort of elderly patients with dementia.26 Blocking dopamine receptors may result in an extrapyramidal effect (dyskinesia, rigidity, and spasm of the oral and pharyngeal muscles), which can result in dysphagia and ultimately in aspiration pneumonia.27 In the present study, the chlorpromazine equivalent dose for antipsychotics was associated with an increase in the risk of pneumonia.

Interestingly, the use of typical antipsychotics was not associated with the development of pneumonia whereas the use of atypical antipsychotics was. Several studies reported similar findings. Knol et al26 reported a higher risk of pneumonia associated with the administration of atypical antipsychotics than of typical antipsychotics in patients with dementia (OR = 3.1 vs 1.5). The risk of extrapyramidal adverse events associated with antipsychotic use was generally lower for atypical than typical antipsychotics.28 Thus, mechanisms other than extrapyramidal adverse events may play a role. The anticholinergic action and blockade of histamine‐1 (H1) receptor by atypical antipsychotics have been proposed as an alternative explanation for the development of pneumonia.26 The anticholinergic effect of antipsychotics could be related to contracting pneumonia by inducing dry mouth and impaired oropharyngeal bolus transport. The blockade of H1 receptors may lead to excessive sedation, which can result in a decreased swallowing reflex and thereby conduce to pneumonia.29 For patients with a high risk of pneumonia, physicians should make an effort to reduce the dose of antipsychotics, especially atypical antipsychotics, if the patient's psychotic symptoms can be controlled.

The present study has several limitations. First, we were unable to evaluate the severity of psychiatric conditions on admission due to the retrospective study design. The severity of schizophrenia itself might affect the patient's ability to swallow, which can in turn affect the development of pneumonia.30 In addition, overdose of benzodiazepines, catatonic stupor, and bedridden status is reportedly risk factors for pneumonia.31 Further study is needed to determine whether the severity of schizophrenia itself and the use of psychoactive drugs other than antipsychotics are also risk factors for pneumonia. Second, our study demonstrated an association between the use of atypical antipsychotics and pneumonia. However, we were unable to determine how and why atypical antipsychotics were used before the patients were admitted to Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital. Thus, whether the use of atypical antipsychotics was a direct cause of pneumonia is uncertain. Third, in our study, 765 patients who moved to another hospital after a few days were not included, possibly influencing our findings. Finally, because this was a retrospective cohort study, a prospective study is needed to validate our results.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that advanced age, underweight, smoking habit, use of atypical antipsychotics, and large doses of antipsychotics were risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. Further study based on our results is needed to establish preventive strategies to reduce pneumonia‐related death among schizophrenic patients with pneumonia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

TH conceived and designed the study, acquired the data and subjects, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. KI, MO, MI, KS conceived and designed the study, acquired the subjects, and prepared the manuscript. KT conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

DATA REPOSITORY

Supporting information Table S1.

APPROVAL OF THE RESEARCH PROTOCOL BY AN INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWER BOARD

All study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital.

INFORMED CONSENT

The approved protocol did not require informed consent from patients, as the protocol was not different from ordinary practice, and as the data remained anonymous and were analyzed in aggregate.

REGISTRY AND THE REGISTRATION NO. OF THE STUDY/TRIAL

n/a.

ANIMAL STUDIES

n/a.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James. R. Valera for his assistance in editing this manuscript.

Haga T, Ito K, Sakashita K, Iguchi M, Ono M, Tatsumi K. Risk factors for pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2018;38:204–209. 10.1002/npr2.12034

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn (DSM‐5) Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen YH, Lee HC, Lin HC. Mortality among psychiatric patients in Taiwan–results from a universal National Health Insurance programme. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Filik R, Sipos A, Kehoe PG, et al. The cardiovascular and respiratory health of people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lim LC, Sim LP, Chiam PC. Mortality among psychiatric inpatients in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1991;32:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hewer W, Rössler W, Fätkenheuer B, Löffler W. Mortality among patients in psychiatric hospitals in Germany. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Polednak AP. Respiratory disease mortality in an institutionalised mentally retarded population. J Ment Defic Res. 1975;19:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chou FH, Tsai KY, Chou YM. The incidence and all‐cause mortality of pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia: a nine‐year follow‐up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seminog OO, Goldacre MJ. Risk of pneumonia and pneumococcal disease in people with severe mental illness: English record linkage studies. Thorax. 2013;68:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koivula I, Sten M, Mäkelä PH. Risk factors for pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Med. 1994;96:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farr BM, Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT, et al. Risk factors for community‐acquired pneumonia diagnosed by general practitioners in the community. Respir Med. 2000;94:422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Balanzó X, González CA. Risk factors for community‐acquired pneumonia in adults: a population‐based case‐control study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haga T, Ito K, Ono M, et al. Underweight and hypoalbuminemia as risk indicators for mortality among psychiatric patients with medical comorbidities. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71:807–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . The International Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toru M. Antipsyhchotics. Rinsho Seishin Igaku. 1995;10(Suppl):60–64. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gavazzi G, Krause KH. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robertson RG, Montagnini M. Geriatric failure to thrive. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freeman MC, Garn JV, Sclar GD, et al. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220:928–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO Expert Committee . Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Serra‐Prat M, et al. New evidence of risk factors for community‐acquired pneumonia: a population‐based study. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1274–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sugai T, Suzuki Y, Yamazaki M, et al. High prevalence of underweight and undernutrition in Japanese inpatients with schizophrenia: a nationwide survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prochaska JJ. Smoking and mental illness–breaking the link. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:196–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cavazos‐Rehg PA, Breslau N, Hatsukami D, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with lower rates of mood/anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2523–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knol W, van Marum RJ, Jansen PA, Souverein PC, Schobben AF, Egberts AC. Antipsychotic drug use and risk of pneumonia in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sliwa JA, Lis S. Drug‐induced dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wada H, Nakajoh K, Satoh‐Nakagawa T, et al. Risk factors of aspiration pneumonia in Alzheimer's disease patients. Gerontology. 2001;47:271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schindler JS, Kelly JH. Swallowing disorders in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:589–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kulkarni DP, Kamath VD, Stewart JT. Swallowing disorders in schizophrenia. Dysphagia. 2017;32:467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Funayama M, Takata T, Koreki A, Ogino S, Mimura M. Catatonic stupor in schizophrenic disorders and subsequent medical complications and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials