Abstract

Introduction

Preclinical testing in animal models is a critical component of the drug discovery and development process. While hundreds of interventions have demonstrated preclinical efficacy for ameliorating cognitive impairments in animal models, none have confirmed efficacy in Alzheimer's disease (AD) clinical trials. Critically this lack of translation to the clinic points in part to issues with the animal models, the preclinical assays used, and lack of scientific rigor and reproducibility during execution. In an effort to improve this translation, the Preclinical Testing Core (PTC) of the Model Organism Development and Evaluation for Late‐onset AD (MODEL‐AD) consortium has established a rigorous screening strategy with go/no‐go decision points that permits unbiased assessments of therapeutic agents.

Methods

An initial screen evaluates drug stability, formulation, and pharmacokinetics (PK) to confirm appreciable brain exposure in the disease model at the pathologically relevant ages, followed by pharmacodynamics (PD) and predictive PK/PD modeling to inform the dose regimen for long‐term studies. The secondary screen evaluates target engagement and disease modifying activity using non‐invasive positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging (PET/MRI). Provided the compound meets its “go” criteria for these endpoints, evaluation for efficacy on behavioral endpoints are conducted.

Results

Validation of this pipeline using tool compounds revealed the importance of critical quality control (QC) steps that researchers need to be aware of when executing preclinical studies. These include confirmation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient and at the precise concentration expected; and an experimental design that is well powered and in line with the Animal Research Reporting of In vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Discussion

Taken together our experience executing a rigorous screening strategy with QC checkpoints provides insight to the challenges of conducting translational studies in animal models. The PTC pipeline is a National Institute on Aging (NIA)‐supported resource accessible to the research community for investigators to nominate compounds for testing (https://stopadportal.synapse.org/), and these resources will ultimately enable better translational studies to be conducted.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, drug screening, mouse models, preclinical testing, translational approaches

1. INTRODUCTION

Throughout the last several decades there have been considerable efforts to develop disease‐ameliorating treatments which stop, prevent, or delay Alzheimer's disease (AD). 1 , 2 Unfortunately, while hundreds of interventions from a range of drug classes have shown preclinical efficacy in ameliorating cognitive impairment and disease burden in animal models, none to date have proven efficacious for improving cognition in human clinical trials. 2 , 3 , 4

Preclinical testing in animal models is a critical component of the drug discovery and development process, to predict both a compound's efficacy and safety profile in the clinic. Historically, preclinical screening of test compounds for AD have used behavioral endpoints in rodent models as the primary screen. 4 A review of the literature and the Alzheimer's disease preclinical efficacy database AlzPED (see https://alzped.nia.nih.gov), provides insight into these preclinical behavioral studies which have often been misinterpreted, including ignoring confounds of hyperactivity and visual impairments on cognitive behaviors in aging animals, along with failure to determine pharmacokinetics (PK) in the model system. 5 These experiments have frequently failed to transparently report critical details of the experimental design, including rigor in methods for blinding, randomization, counterbalancing, inclusion of appropriate controls, and statistically powered sample size selection, which are fundamental aspects of Animal Research Reporting of In vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Further, testing has often been conducted in young animals, and often limited to only one sex. Moreover, preclinical AD studies have rarely used molecular biomarkers, or other clinically translational endpoints as PD readouts (ie, positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging [PET/MRI]). While there is value in functional, symptom‐modifying outcome measures, these should be considered once biomarker changes have been shown to result in a dose‐, or concentration‐, dependent manner consistent with target engagement in the tissue of interest. Indeed, while the mouse remains an important animal model system for evaluating potential therapeutic efficacy for AD, it is imperative that researchers promote responsible use of these models for preclinical drug testing.

In an effort to improve preclinical to clinical translation, the Preclinical Testing Core (PTC) of the Model Organism Development for Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease (MODEL‐AD) consortium is responsive to the 2012 and 2015 National Institute on Aging (NIA) AD Research Summit recommendations on increasing the predictive power of preclinical testing in animal models. 8 , 9 This includes establishment of rigorous and standardized protocols, which implement best practices for preclinical screening of therapeutic compounds, and importantly prioritizes PK and pharmacodynamics (PD) measures over cognitive measures as the primary screen in mouse models. 8 , 9 Critically, all raw and analyzed data, including negative and positive findings, are reported to the public data repository (https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/).

2. METHODS

The PTC has established a rigorous screening strategy with a priori go/no‐go decision points that allow unbiased assessments of potential therapeutic agents and critical quality control (QC) checkpoints as part of best practices (Figure 1). As part of establishing this screening strategy, to optimize protocols and validate the pipeline, the PTC evaluated a well‐characterized clinical tool compound, the beta‐secretase one inhibitor MK‐8931 (verubecestat). In line with the PTC's precision medicine approach, the mechanism of action of verubecestat was matched to a well‐characterized model system with a relevant AD biomarker (eg, robust amyloid deposition) that enabled in vivo target engagement; 5XFAD mice (B6.Cg‐Tg [APPSwFlLon,PSEN1*M146L*L286V]6799Vas/Mmjax; JAX#34848). Prior to initiating long term chronic dosing studies, qualification and confirmation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) by liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) was performed, along with drug formulation and stability assessments. Once confirmed, PK studies were conducted in 5XFAD mice (n = 3–4 per sex/dose) at pathophysiological relevant ages (eg, 6 months) to confirm brain exposure. Predictive PK/PD modeling was conducted to inform the study design, including optimal dosing regimens (ie, dose, route, frequency) for long‐term PD studies. After the primary screen, non‐invasive PET/MRI were conducted to evaluate target engagement after chronic treatment (n = 10‐15 per sex/dose). For the present studies, the clinical radio‐tracer 18F‐AV45 PET was used to evaluate alterations of amyloid as the PD endpoint. Mice were injected with 5 to 7MBq of 18F‐AV45 via tail vein, allowed 30 minutes uptake in their home cages, and then scanned for 15 minutes on IndyPET3. Corrected images (ie, decay, scatter, dead‐time, etc) were reconstructed via filtered back‐projection, registered to the Paxinos‐Franklin atlas, 27 brain regions extracted, and standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR; ie, relative to cerebellum) values computed. Provided the compound meets its criteria for these endpoints, evaluation of behavioral endpoints are conducted. All experiments are conducted in line with the ARRIVE guidelines and carried out in line with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). 7 All detailed methods and data including animal husbandry and breeding conditions as well as assay standard operating procedures (SOPs) are available via https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org and www.model-ad.org. 9

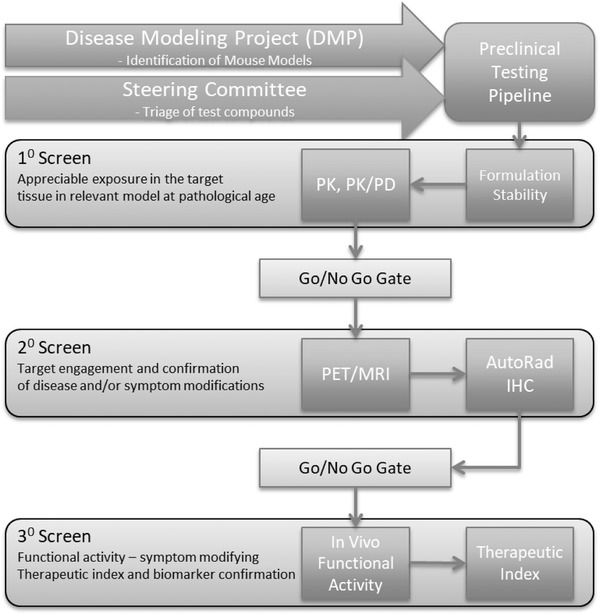

FIGURE 1.

The Model Organism Development for Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease (MODEL‐AD) Preclinical Testing Core (PTC) Drug Screening pipeline. The PTC strategy includes a primary screen to determine: drug conformation of active pharmaceutical ingredient; formulation and drug stability; in vivo pharmacokinetics (PK), and target tissue concentrations in models at disease‐relevant ages. A secondary screen evaluates target disease modifying activity using non‐invasive positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging as a pharmacodynamics (PD) readout matched to known disease pathology in the model. Mouse models are best matched to mechanism of action of compound being evaluated relative to model disease trajectory and pathophysiology. Compounds demonstrating positive PD effects in the secondary screen are further interrogated via a tertiary screen of functional assays that assess the compound's ability to normalize a disease‐related phenotype in cognition and neurophysiological tests, as well as a therapeutic index relative to any adverse effects. The final component of the PTC screen includes confirmatory pharmacokinetics, genotyping quality control, and post treatment transcriptomics. The PTC pipeline is a National Institute on Aging‐funded resource accessible to the research community via the Screening the Optimal Pharmaceutical for Alzheimer's Disease (STOP‐AD) program (https://stopadportal.synapse.org)

3. RESULTS

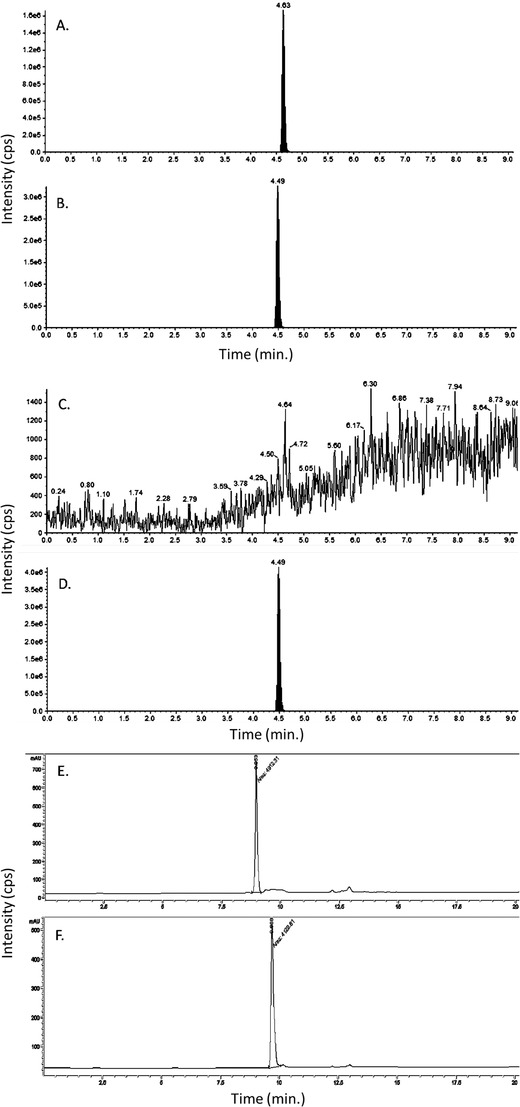

The LC/MS/MS assay was developed in the Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Core using verubecestat triflouroacetate purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Cat #S8173; standard). Figure 2(A‐D) shows the resulting LC/MS/MS chromatograms of the verubecestat standard (2A) and corresponding internal standard MK‐2206 (2B), and the custom batch API (2C) and corresponding MK‐2206 (2D). Analysis of the custom bulk synthesis batch of verubecestat from the same vendor was not detectable using this assay. To evaluate this discrepancy, the method was transferred to a liquid chromatography/ultraviolet (LC/UV) system (λ = 280 nm). Injecting both the standard and the custom batch revealed that the standard eluted at 8.953 minutes (2E) while the custom batch API eluted at 9.666 minutes (2F). Further analyses concluded that the custom batch API did not contain verubecestat. The vendor subsequently replaced the custom batch API, which was confirmed as verubecestat. Acute oral administration to 6 months aged 5XFAD mice for PK analysis revealed a short half‐life for verubecestat (ie, T1/2 = 2.7 hours), which would require multiple daily administrations via oral dosing over a 3‐month period to maintain targeted exposure levels in the brain. To avoid significant stress and attrition related to daily oral gavage, the API was sent to a commercial vendor and milled into chow. Two batches of pellets underwent QC prior to dosing, which revealed erroneous mislabeling by the vendor. After correcting these anomalies, inter‐ and intra‐pellet analyses were conducted to confirm drug concentration in pelleted chow. Inter‐pellet analysis revealed an average 54 ± 17% and 59 ± 16% of expected drug concentrations, in batch 1 and batch 2, respectively. Intra‐pellet analysis revealed unequal distribution with coefficient of variation ranging from 8% to 36%. These data coupled with the pilot PK data provided additional information for PK/PD modeling to better calculate the range of drug concentrations required to be formulated into chow to achieve adequate exposure levels in the brain. The designated dose levels of 60, 100, and 600 parts per million were therefore formulated to achieve estimated daily dosages of 10, 30, and 100 mg/kg/day, fed ad libitum in chow, and were in line with our PK data and published EC50 for verubecestat. 10 Subsequently, analysis of chronic verubecestat exposure on amyloid levels resulted in expected dose dependent reductions in amyloid in both sexes as measured by 18F‐AV45 PET SUVR, in line with clinical findings. 10

FIGURE 2.

Validation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient of verubecestat. Chromatogram of standard verubecestat (A), catalog S8564, and MK‐2206 (B) the internal standard injected to liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) system. The filled peak is the analyte of interest. Chromatogram of custom batch active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) verubecestat (C), catalog S8564, and MK‐2206 (D) the internal standard injected to LC/MS/MS system. The filled peak is the analyte of interest. Chromatogram of standard verubecestat (E) at retention time 8.953 minutes, and custom batch API verubecestat (F) at retention time 9.666 minutes determined not to be the correct API for verubecestat, injected to liquid chromatography/ultraviolet (LC/UV) system

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (eg, PubMed) and new sources (eg, AlzPED), as well as face to face discussions with scientists on approaches to preclinical testing in animal models. It was clear that a majority of studies have not been executed with the level of rigor used in clinical trials, including gaps in methods for blinding, a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria, predetermined sample sizes, randomization, and data quality control measures. Further, testing is often conducted opportunistically in the animal model most readily available to the laboratory, rather than matching the mechanism of action to the most appropriate model for in vivo target engagement and relevant biomarkers.

Interpretation: Our findings highlight a need for improved methodologies and resources for the research community.

Future directions: We propose a framework for improved rigor in preclinical testing that will ultimately enable better translation from animal models to clinical studies.

4. DISCUSSION

Like most preclinical efficacy studies for AD, our pipeline includes chronic dosing of test compound in aged mice. However, we also include several crucial steps prior to the chronic dosing, namely: (1) QC and stability testing of the API; and (2) initial PK and PD modeling to inform the dose regimen. These initial data confirm that the API is the intended compound, and that the dose regimen selected achieves the expected concentrations in the target tissue. Failure of either scenario could result in false negative results, and months of wasted time, efforts, resources, and precious animals. In the present studies, the initial QC steps allowed us to correct issues with drug formulations prior to advancing with the chronic study, which would have ultimately resulted in unexplained failure. Moreover, QC of the drug concentration in the intended formulation, including in food, are critical aspects for success. Ideally in vivo PK should be determined prior to initiating long term studies to understand the kinetic properties and drug uptake at the active site. For most AD therapies, this will include understanding of blood‐brain barrier permeability and tissue exposure. At a minimum, the API should be assessed in plasma and brain as part of the terminal procedures to confirm target exposure. Importantly, these aforementioned fail‐safes permitted advancement of this study, and resulted in the expected dose‐dependent reduction in beta amyloid as measured by 18F‐AV45 PET SUVR.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Evaluation of potential therapeutic efficacy of test compounds in animal models is not trivial. Emphasis on QC steps is an essential part of rigor in experimental design, and unfamiliarity of these steps is an unfortunate common point of failure. Our collective prior experience provided us knowledge of potential areas for errors in our pipeline including those in the synthesis and formulation of drug as presented in the present studies. Using best practices, and multiple levels of QC, are critical for confirming appreciable exposure at the target tissue, correlating concentration with in vivo target engagement, and identifying reasons why drug may have failed to demonstrate the expected response. Practicing these processes may ultimately enable better preclinical to clinical translation and development of effective treatments for Alzheimer's disease. Importantly, the preclinical screening pipeline is an NIA‐funded resource available to the research community through the Screening the Optimal Pharmaceutical for Alzheimer's Disease (STOP‐AD) program (https://.stopadportal.synapse.org). 11

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors are supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging U54 AG05434503, 1R13AG060708‐01. Bruce T. Lamb has served as a consultant for AvroBio and Eli‐Lilly, and is supported by additional funding: NIA R01 AG022304, RF1 AG051495, U54 AG065181, U54 AG054345. Mass spectrometry and UV work was provided by the Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Core at Indiana University School of Medicine; a core facility supported by the IU Simon Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA082709.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the exceptional technical support of MODEL‐AD colleagues: K. Keezer, L. Haynes, G. Little, S.‐P. Williams, Z. Cope, C. Biesdorf, D. R. Jones, J. A. Meyer, J. Peters, S. C. Persohn, B. R. McCarthy, A. A. Riley, L. L. Figueiredo, K. Eldridge, R. Speedy; and to Dr. Rebecca Edelmayer for critical review and valuable feedback of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging U54 AG05434503, 1R13AG060708‐01. Mass spectrometry and UV work was provided by the Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Core at Indiana University School of Medicine; a core facility supported by the IU Simon Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA082709.

Sukoff Rizzo SJ, Masters A, Onos KD, et al. Improving preclinical to clinical translation in Alzheimer's disease research. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;6:e12038 10.1002/trc2.12038

REFERENCES

- 1. Khachaturian AS, Paul SM, Khachaturian ZS. NAPA 2.0: the next giant leap. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:379‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cummings JL, Morstorf T, Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug‐development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shineman DW, Basi GS, Bizon JL, et al. Accelerating drug discovery for Alzheimer's disease: best practices for preclinical animal studies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bales KR. The value and limitations of transgenic mouse models used in drug discovery for Alzheimer's disease: an update. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012;7:281‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. AlzPED—Alzheimer's Preclinical Efficacy Database . 2017. AlzPED study inclusion methods. https://alzped.nia.nih.gov/alzped-study-inclusion-methods (accessed March 15, 2020).

- 6. Snyder HM, Shineman DW, Friedman LG, et al. Guidelines to improve animal study design and reproducibility for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: for funders and researchers. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(11):1177‐1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: the ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLOS Biology. 2012;8(6):e1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alzheimer's Research Summit, 2012. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/alzheimers-disease-research-summit-offers-research-recommendations (accessed March, 15, 2020)

- 9. MODEL‐AD: Model Organism Development for Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease. 2017. https://model-ad.org. (accessed March 15, 2020).

- 10. Kennedy ME, Stamford AW, Chen X, et al. The BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat (MK‐8931) reduces CNS β‐amyloid in animal models and in Alzheimer's disease patients. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(363):363ra150. PMID: 27807285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Screening The Optimal Pharmaceutical for Alzheimer's Disease (STOP‐AD). 2020. https://stopadportal.synapse.org. (accessed March 20, 2020).