Abstract

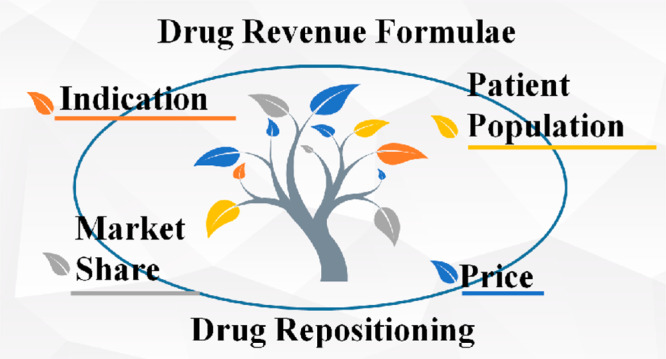

As a business model, drug repositioning is facing increasing challenges from both academia and industry. To examine the feasibility of drug repositioning as a systematical business model, a drug revenue formula is introduced. By breaking down key factors into indication, price, patient population, and market share, the potentiality of the drug repositioing business model is confirmed. In addition, some unworkable repositioning stratgies are also summarized.

Keywords: Drug repositioning, external innovation, drug repurposing, drug rescue

It is usually reasonable to repurpose drugs or failed drug candidates for new uses.1 However, most drug repositioning cases occur more by chance than design. Although some big pharmas already have their own drug repositioning units (such as Pfizer’s Indications Discovery Unit established in 2007), it is still very hard for enterprises only focusing on drug repositioning efforts to meet sustainable success. In this article some real-world practices have been carefully examined.

Case 1: Axovant Gene Therapies is a U.S. pharma founded in 2014. Its initial strategy focused on “repurposing drugs developed by other companies”.2 However, following a series of clinical trial fails and the departure of its CEO, Axovant experienced ∼90% slump of market capitalization and gradually transfers its focus from repurposing to R&D cooperation (such as the license-in of OXB-102).

Some scholars and industry veterans do not believe drug repositioning can work as a profitable business model. Among them, John LaMattina, former R&D president at Pfizer, expressed his idea most clearly by stating “Can some repositioning projects work? Sure. Can it work systematically as a profitable business model? That, I don’t believe...It’s a bit naive to think that companies overlook all these opportunities to do business”.3

Nevertheless, LaMattina did not further deliver a detailed analysis by breaking down related factors. Therefore, it is necessary to re-evaluate the feasibility of drug repositioning as a separate, systematical, sustainable business model.

Formulas to Evaluate the Function of a Drug Repositioning Business Model

To evaluate the function of a drug repositioing business model, we can consider some key factors determining the revenue of a drug:4,5

i = indication

In real-world practices, looking at business model innovation, we can examine four drug repositioning strategies, aimed at changing indication, price, patient population, and market share, respectively.

Drug Repositioning Strategy to Change Indication

Most successful drug repositioning cases are aimed to repurposing drugs for a new indication.6,7 Dimebon, a drug for Alzheimer’s disease, is a typical example.8 Another notable case is Thalomid of Celgene. Most pharmas cannot complete these processes by themselves: a pharma may only cover some specific indications or sectors, so it is more reasonable for pharmas to utilize external alliance for achieving clinical research and sales. In these cases, separate and systematical drug repositioning partners can definitely provide help.

Case 2: PharmaKure is a British pharma founded in 2013, with a particular strategy of discovering new uses for known compounds or drugs through its phenotypic screening methods.

Drug Repositioning Strategy to Change Price

Some drug repositioning projects can lead to the change of price. When the formulation is changed, the dose for a new indication can be reduced while the price per unit weight can be increased.

Drug Repositioning Strategy to Change Patient Population

This strategy can also be referred to as drug racializing, which reidentifies a drug’s patients by phenotype.9 Drug racializing owes its success to human genomics technology, developed 20 years ago but not used in drug R&D until recently.10 In these cases, a partner in a foreign country can provide help on localized R&D dynamics.

Case 3: Denovo Biopharma is a U.S./China pharma founded in 2011, focusing on acquiring failed drug candidates in the U.S. or EU and then exploring their potentialities on an Asian population (Table 1).

Table 1. Real-World Practices of Drug Repositioning Business Model.

| Corporation | Founded | Headquarter | Status | Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axovant Gene | 2014 | New York | IPO | 3 Ph1/2 |

| PharmaKure | 2013 | Manchester | Seed Round Financing | 1 Preclinical |

| Denovo Biopharma | 2011 | San Diego | Series B Financing | 1 Ph3; 2 Ph2; 2 Ph1 |

Corporate status and pipeline data were updated on April 1, 2020.

Drug Repositioning Strategy to Change Market Share

As mentioned above, most pharmas do not have R&D experience and sales teams across all indications. As a result, most repositioning partners will have additional sales teams for a better market share. A one-stop service will make the drug repositioning business model stronger.

Taking Precautions against Repositioning Projects Outside the Formulas

On the contrary, any repositioning projects outside the framework should be carefully reviewed. Start-ups may in-license reposition projects to expand their pipelines for higher corporate valuations. These repositioning projects do not provide any positive changes to the formulas of drug revenue and will usually be terminated after the achievement of corporate financing.

Case 4: Adlai Nortye, a China pharma founded in 2016, in-licensed Buparlisib from Novertis. With limited revenue (<$70 million; estimated by Adlai Nortye) after narrowing patient population, the drug candidate is usually regarded as a temporary asset in the pipeline to support higher corporation valuation.

There are also other cases of negative repositioning projects. For example, the dosage regimen may be changed and hence the projects will lose policy advantages on a Phase I trial waiver. These endeavors do not provide core improvements on drug value/revenue but only depend on policy supports and R&D cost advantages. In other words, these endeavors outside the formulas can be easily replaced by pharmaceutical companies and hence cannot lead to a separate, systematical, sustainable business model.

Conclusion

The essence of a separate drug repositioning partner is to provide external innovation dynamic and R&D outsourcing. As external innovation is becoming increasingly significant in the pharmaceutical value chain,11−13 we can assume drug repositioning will work as a systematical business model in the near future. Whereas the future of drug repositioning is positive, we should take care of unworkable drug repositioning: these kinds of drug repositioning do not contribute to any factor in drug revenue formulas and hence do not add additional value.

Views expressed in this editorial are those of the author and not necessarily the views of the ACS.

The author declares no competing financial interest.

References

- Naylor S.; Schonfeld J. M.. Therapeutic Drug Repurposing, Repositioning and Rescue Part II: Business Review. Drug Discov. World; Spring ed.: 2015; pp 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P.Axovant bets on gene therapy with $842.5m Oxford BioMedica deal: big departure from repurposing. PMLive, Jun 2018. www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/axovant_bets_on_gene_therapy_with_$842.5m_oxford_biomedica_deal_1238746 [accessed on 2020-03–-19].

- Nosengo N. Can You Teach Old Drugs New Tricks?. Nature 2016, 534 (7607), 314–316. 10.1038/534314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villiger R.; Bogdan B.. Valuation in Life Sciences: A Practical Guide; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Austin M.Business Development for the Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Industry; Ashgate Publishing Group, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pantziarka P.; Pirmohamed M.; Mirza N. New Uses for Old Drugs. BMJ 2018, 361, k2701. 10.1136/bmj.k2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs R. E.; Ginsburg P. B.; Goldman D. P. Encouraging New Uses for Old Drugs. JAMA 2017, 318 (24), 2421–2422. 10.1001/jama.2017.17535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A.; Jacoby R. Dimebon in Alzheimer’s Disease: Old Drug for New Indication. Lancet 2008, 372 (9634), 179–180. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zissimopoulos J. M.; Barthold D.; Brinton R. D.; Joyce G. Sex and Race Differences in the Association between Statin Use and the Incidence of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 2017, 74 (2), 225–232. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. S. Racializing Drug Design: Implications of Pharmacogenomics for Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95 (12), 2133–2138. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan C. Industry Continues Dabbling with Open Innovation models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 1063–1065. 10.1038/nbt1211-1063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Plump A.; Ringel M. Racing to Define Pharmaceutical R&D External Innovation Models. Drug Discovery Today 2015, 20 (3), 361–370. 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufféry; Pierre Accessing External Innovation in Drug Discovery and Development. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2015, 10 (6), 579–589. 10.1517/17460441.2015.1040759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]