to the editor: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak has become a public health emergency globally.1, 2 Until 26 May 2020, there were 7126 confirmed cases reported in Australia (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). However, specimens of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) independently isolated in Australia (in Sydney, the Gold Coast and Melbourne)3 exhibited very unusual mutations, which have not been identified in other countries (Box, A).

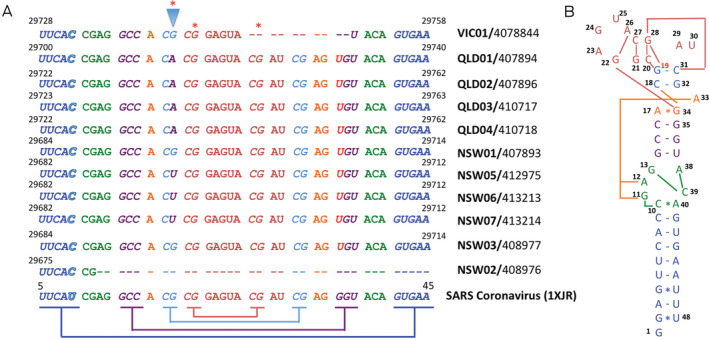

Box 1. Mutations, deletions and recombination breakpoints in the stem‐loop II motif (s2m) of Australian severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) isolates.

Panel A: Deletions and mutations in the primary, secondary and tertiary structures of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) s2m RNA genetic element based on the three‐dimensional crystal structure of the SARS virus. Conventional RNA helical base pairings are indicated in italics. Sequence complements are indicated using colour‐coded brackets. The G19 mutation (arrowhead) of the Australian SARS‐CoV‐2 is shown with purple colour. Asterisks label the RNA recombination breakpoints based on analysis of 1319 Australia SARS‐CoV‐2 sequences using Recco algorithm (https://recco.bioinf.mpi-inf.mpg.de/) (P < 0.002). Panel B: Schematic representation of the s2m RNA secondary structure of the SARS virus, with tertiary structural interactions indicated as long range contacts.4

Up to 29 April, 1319 sequences of the Australian SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates are available in the website of the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID).3 Except for the NSW03 and NSW01 isolates, viral mutations are located at the stem‐loop II motif (s2m), an extremely conserved RNA element in the 3’ untranslated region (3’‐UTR) (Box, A). The NSW02 and VIC01 isolates have deletion of 41 and ten nucleotides respectively. All Queensland cases have single G‐to‐A substitution (nucleotides 29714/QLD01, 29736/QLD02, 29736/QLD04, and 29737/QLD03). Moreover, patients with NSW05, NSW06, NSW07, NSW15, NSW18, NSW19, NSW21, NSW24, NSW26, NSW28, or NSW31 (nucleotide 29696) have single G‐to‐U substitution at the same nucleotide. This substitution is only present in Australian patients and has not been found in SARS‐CoV‐2 isolates from other countries.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that SARS and 30 other coronaviruses and astroviruses all possess the genetic element s2m, suggesting that this motif is conserved in both nucleotide sequence and secondary structure folding during evolution in an otherwise rapidly mutable RNA genome.3, 5 The three‐dimensional crystal structure of the s2m RNA element of the SARS virus shows that guanosine (19), which is mutated in Australian isolates, is critical for tertiary contacts to form an RNA base quartet involving two adjacent G–C pairs (G19, C20, G28, and C31)4 (Box, B). Because s2m plays an essential role for the viral RNA to substitute host protein synthesis, we hypothesise that the disruption of s2m could alter the viral viability or infectivity dramatically.

The s2m sequence of coronaviruses is highly conserved, and spontaneous mutations in this motif were not expected to have occurred during the apparent short period when SARS‐CoV‐2 has been present; therefore, it is highly likely that the changes are due to recombination.5 Because a high frequency of recombination events in coronaviruses occurs, RNA recombination could either enhance the adaptation process to its new host like humans or cause unpredictable changes in virulence during infection.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

The unedited version of this article was published as a preprint on mja.com.au on 15 May 2020.

References

- 1. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020; 395: 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. COVID‐19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team ; Department of Health. COVID‐19, Australia: epidemiology report 13: reporting week ending 23:59 AEST 26 April 2020. Commun Dis Intell 2020; 44; 10.33321/cdi.2020.44.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) . EpiCoV: pandemic coronavirus causing COVID‐19. https://gisaid.org (viewed Apr 2020).

- 4. Robertson MP, Igel H, Baertsch R, et al. The structure of a rigorously conserved RNA element within the SARS virus genome. PLoS Biol 2005; 3: e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tengs T, Jonassen C. Distribution and evolutionary history of the mobile genetic element s2m in coronaviruses. Diseases 2016; 4: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]