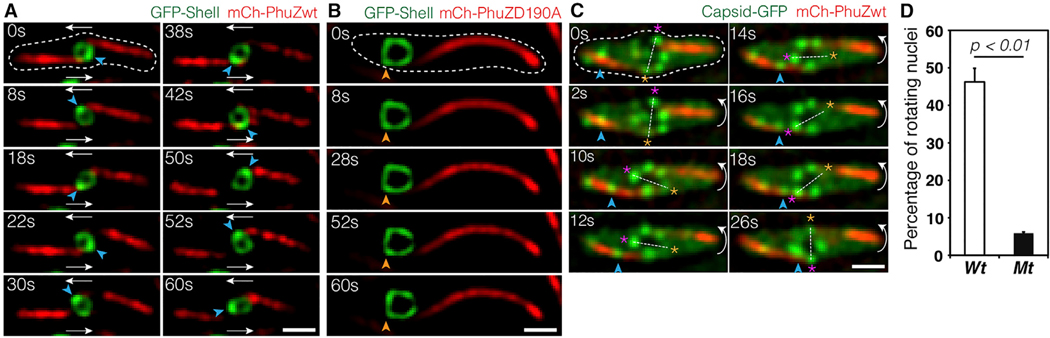

Figure 4. Rotation of the Phage Nucleus Exerted by PhuZ Spindle Distribute Phage Capsids around the Nucleus.

(A and B) Rapid time-lapse imaging of phage 201Φ2–1-infected P. chlororaphis expressing GFP-tagged shell (gp105) with either mCherry-tagged wild-type PhuZ (gp059) (A) or mCherry-tagged mutant PhuZD190A (gp059) (B) during 60 s intervals. In the presence of wild-type filaments, the shell (green) rotates counter-clockwise when the PhuZ filaments push the shell transversely; the shell successfully rotates twice within 42 s. The mutant PhuZD190A is unable to catalyze GTP hydrolysis and appears static, resulting in a mispositioned and motionless shell within the infected cell. See also Data S1 (see Movies 7 and 8).

(C) Rapid time-lapse microscopy of phage 201Φ2–1-infected P. chlororaphis expressing GFP-tagged capsid (gp200) and mCherry-tagged wild-type PhuZ (gp059) in a 26 s interval. A capsid (arrow) travels along the filament from cell pole toward the phage nucleus, which rotates counterclockwise. The capsid docks on the surface of the nucleus at 26 s. Dashed lines indicate cell borders. Scale bars, 1 micron. See also Data S1 (see Movie 9).

(D) Graph showing the percentage of rotating nuclei in P. chlororaphis infected cells in the presence of either wild-type PhuZ (wt) or mutant PhuZD190A (mt). The graph shows that the number of rotating nuclei in the presence of wild-type PhuZ (46.2%) is significantly higher (p < 0.01) than that in the presence of mutant PhuZD190A (5.9%). Data were collected from infected cells at 50 mpi from at least three different fields and are represented as mean ± SE (n; wt = 611 and mt = 286).

See also Figure S4.