Compared to the standard two-tiered testing (STTT) algorithm for Lyme disease serology using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by Western blotting, data from the United States suggest that a modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) algorithm employing two EIAs has improved sensitivity to detect early localized Borrelia burgdorferi infections without compromising specificity. From 2011 to 2014, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where Lyme disease is hyperendemic, sera submitted for Lyme disease testing were subjected to a whole-cell EIA, followed by C6 EIA and subsequently IgM and/or IgG immunoblots on sera with EIA-positive or equivocal results.

KEYWORDS: Lyme disease, serology, modified two-tiered test (MTTT), specificity

ABSTRACT

Compared to the standard two-tiered testing (STTT) algorithm for Lyme disease serology using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by Western blotting, data from the United States suggest that a modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) algorithm employing two EIAs has improved sensitivity to detect early localized Borrelia burgdorferi infections without compromising specificity. From 2011 to 2014, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where Lyme disease is hyperendemic, sera submitted for Lyme disease testing were subjected to a whole-cell EIA, followed by C6 EIA and subsequently IgM and/or IgG immunoblots on sera with EIA-positive or equivocal results. Here, we evaluate the effectiveness of the MTTT algorithm compared to the STTT approach in a Nova Scotian population. Retrospective chart reviews were performed on patients testing positive with the whole-cell and C6 EIAs (i.e., the MTTT algorithm). Patients were classified as having Lyme disease if they had a positive STTT result, a negative STTT result but symptoms consistent with Lyme disease, or evidence of seroconversion on paired specimens. Of the 10,253 specimens tested for Lyme disease serology, 9,806 (95.6%) were negative. Of 447 patients who tested positive, 271 charts were available for review, and 227 were classified as patients with Lyme disease. The MTTT algorithm detected 25% more early infections with a specificity of 99.56% (99.41 to 99.68%) compared to the STTT. These are the first Canadian data to show that serology using a whole-cell sonicate EIA followed by a C6 EIA (MTTT) had improved sensitivity for detecting early B. burgdorferi infection with specificity similar to that of two-tiered testing using Western blots.

INTRODUCTION

Lyme disease (LD) is an emerging vector-borne infection in North America caused by a spirochete belonging to the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex that is transmitted by the bite of an infected blacklegged tick (BLT). Since LD became nationally notifiable in 2009, the number of reported cases of LD in Canada has increased from 144 to 2,025 in 2017 (1). The majority (approximately 90%) of these cases have been in areas where infected BLT populations are known to occur in the provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia (2). However, the true number of LD cases in Canada is likely underestimated (3, 4), and as the geographic range of BLTs continues to expand, more Canadians will be at risk of acquiring LD (5, 6). In Nova Scotia, the first case of LD was identified in 2002, and case numbers have steadily risen from 17 in 2009 to 586 in 2017. The province has emerged as a place where the disease is hyperendemic, and overall, it has the highest incidence of LD in Canada (2, 4, 7, 8).

The clinical presentation of LD depends on the stage of infection. Early localized infection commonly presents with an expanding erythematous rash called erythema migrans (EM), but the rash may be absent in approximately 20% of cases (9). If the rash is absent or missed and untreated, the bacteria causing LD can disseminate throughout the body and present as early disseminated infection, with manifestations such as multifocal EM rash, nonspecific influenza-like illness, arthralgia, meningitis, neuropathy, or carditis. Finally, if left untreated, the infection can progress to late disseminated disease, with oligoarthritis in larger joints, and less commonly as neurologic disease (10).

The current reference method for laboratory diagnosis of LD is serology, which detects antibodies to B. burgdorferi using standard two-tiered testing (STTT), which uses an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by IgM and/or IgG immunoblots (IBs). The performance characteristics of the STTT algorithm depend on the stage of infection. A recent systematic review has shown that the sensitivity of serology for LD is poor in early localized infection (<50%), but the algorithm performs well in late stages of the infection, where the sensitivity approaches 100% (11). As such, diagnosis and treatment of early localized LD is based on clinical symptoms alone in patients who have been exposed to BLTs in an area of endemicity (12). However, the diagnosis of early LD can be challenging, since some patients with early localized B. burgdorferi infection do not present with the EM rash and may have symptoms that overlap those of other diseases (9). Given these challenges, patient samples for LD serology are still submitted to clinical laboratories, and improving test sensitivity for early localized infection would be of value.

Many different EIAs are available for the first step in the STTT algorithm, including those manufactured using the whole-cell sonicate (WCS) of B. burgdorferi and more recent assays using conserved synthetic peptides, such as the surface lipoprotein VlsE (variable major protein-like sequence, expressed) or C6 (invariable region 6 of VlsE) or C10 (the conserved amino-terminal portion of outer surface protein C) peptide (13, 14). Although the specificity of the second-generation EIAs is better than that of the WCS, the use of IBs as supplemental tests is required for optimal specificity (14, 15). However, IBs are more laborious to perform than EIAs; the scoring of IBs can be subjective, which may lead to inter- and intralaboratory variability (14); and IB testing is currently performed only at provincial laboratories in British Columbia and Ontario, as well as at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML). Simplification of the current testing strategy would shorten turnaround time and improve patient management.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved a modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) algorithm for LD serology in which a second EIA is used instead of the IBs for samples that test positive or equivocal on the first EIA (16). This MTTT has now been endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an acceptable alternative to STTT (17). Compared to the traditional STTT, The MTTT algorithms improve sensitivity to detect early infections and have equivalent sensitivity for detecting late-stage infections and comparable specificity (18–21). To date, no data from outside the United States have been published using an MTTT algorithm. In this study, the clinical experience of LD testing in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia was reviewed to compare MTTT to the traditional STTT algorithm. The aim was to evaluate whether MTTT consisting of a WCS EIA followed by a C6 EIA would improve sensitivity to detect early B. burgdorferi infection without compromising specificity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serologic testing.

Initial serologic screening for antibodies to B. burgdorferi was done using a commercially available WCS EIA of the B31 strain of B. burgdorferi, B. burgdorferi ELISA II (Wampole Laboratories, Princeton, NJ). Specimens that were equivocal or reactive were sent to the NML (Winnipeg, MB) for supplemental testing using the C6 EIA (Immunetics, Marlborough, MA). Specimens that were equivocal or positive on the C6 EIA were subjected to IgM and/or IgG IB testing (Euroimmun, Luebeck, Germany) and scored using the CDC criteria (22). Because the sensitivity of the STTT is <50% for early localized infection, patients with reactive EIAs and negative IBs could represent false-positive EIAs or false-negative IBs in early infection. All testing was done prospectively and submitted by clinicians as part of clinical management.

Chart review.

To determine whether patients with negative IBs had clinical presentations consistent with LD, a retrospective chart review was undertaken on Nova Scotians who underwent serologic testing for LD from 2011 to 2014 and were found to have both positive WCS and C6 EIAs, irrespective of the IB result. Once permission was obtained from the physician of record, medical records were reviewed, and data were recorded using a standardized data collection tool. The data obtained included demographics, clinical findings that prompted the serologic test, consultations, and treatment. All the data were deidentified, and two investigators independently reviewed the data to classify patients as “true LD” if they had (i) a positive IgG IB, (ii) a negative IgG and positive or negative IgM IB but with any of the signs and symptoms consistent with early LD (e.g., EM rash), or (iii) evidence of seroconversion between consecutive specimens. Although IgM-positive IB within 30 days is consistent with early infection, IgM IB can be falsely positive, so all patients with positive IgM IBs with negative IgG IBs required compatible clinical syndromes to be categorized as true cases. The symptoms and clinical features used to define various LD stages are summarized in Table 1. Patients who did not meet these criteria were considered false-positive cases. In addition, patients were further categorized into stages of LD (Table 1). In the event of a discrepancy in the diagnosis or clinical stage, a third independent investigator reviewed the data and made the final determination. The study was approved by the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Ethics Board.

TABLE 1.

Clinical categorization of LD cases

| LD stage | Clinical featuresa |

|---|---|

| Early localized infection | Presented with rash suggestive of EM or ILI with evidence of seroconversion on subsequent sample (duration of symptoms, <30 days) |

| Early disseminated infection | Presented with disseminated EM or ILI, heart block, neurologic manifestations (meningitis, cranial nerve palsy, or radiculopathy) (duration of symptoms, 30 days to 3 mo) |

| Late disseminated infection | Presented with arthritis or neurologic complaints (duration of symptoms, >3 mo) |

| Posttreatment LD syndrome | Persistent symptoms after treatment without objective findings of ongoing infection |

| Serologic evidence of past infection | No symptoms to suggest current infection with positive IgG IB |

ILI, influenza-like illness.

Statistics.

The proportions of patients with different serologic presentations suggestive of Lyme disease were compared between those whose charts were available for review and those whose charts were not subjected to analysis, using Fisher’s exact test (primary) or a chi-square test (secondary, if the sample size warranted it) at an α of 0.05.

Modeling of MTTT specificity.

The specificity of MTTT was estimated using data from a 2-by-2 contingency table, with the clinical diagnosis used as a comparator. Since the charts of patients with negative WCS and C6 EIAs were not reviewed, a true sensitivity could not be calculated. Specificity was modeled based on estimates of false negatives deduced from true positives observed and sensitivities reported in the literature (15). The confidence intervals (CI) for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were “exact” Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals using the statistical tool on the website Medcalc (https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php).

RESULTS

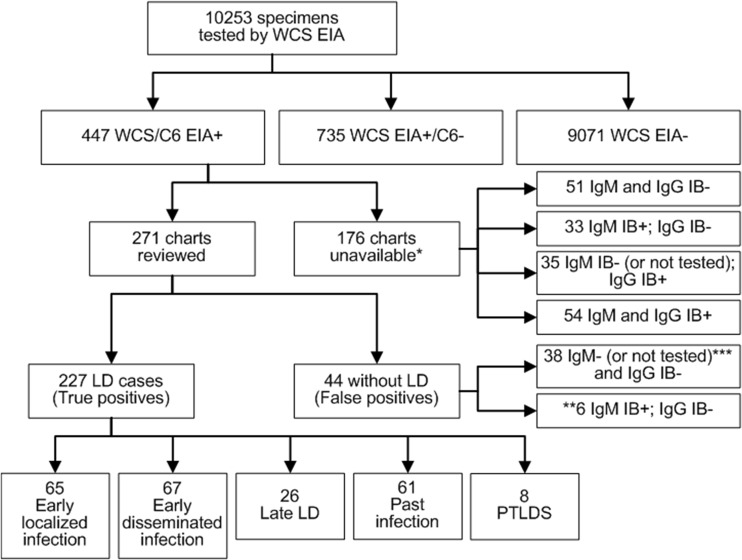

Between 2011 and 2014, LD serology was performed on 10,253 patients, 447 (4.4%) of whom had positive WCS and C6 EIA results (Fig. 1). Of these, 271 (60.6%) had charts available for review (Fig. 1). Most of the patients in the study were from the southern-shore region of Nova Scotia, which has the highest incidence of LD in Canada (4, 7, 8). The ages of the patients reviewed ranged from 1 to 82 years (median age, 49 years), including 38 (14%) who were <16 years old. Of the 271 patients who had charts reviewed, 227 were classified as having LD. The remaining 44 patients were determined to have false-positive WCS/C6 EIA results (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Breakdown of LD serological testing and chart review results. PTLDS, posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome. *, three charts had no IB results. **, of the six individuals who had a positive IgM immunoblot but a negative IgG immunoblot, for two symptoms were ongoing for >30 days and one was diagnosed with optic neuritis and ultimately multiple sclerosis, all consistent with false-positive IgM results; of the remaining three, one patient had 3 days of chest pain and no other symptoms (not a typical presentation for LD), one patient had no clinical data associated with the sample, and one patient had 1 week of subjective fever without documentation of temperature but with no other symptoms. ***, two patients with negative IgG IBs did not have IgM tested, as symptoms were ongoing for >30 days.

MTTT identified additional cases in early localized and early disseminated infections.

Of the 227 patients classified as having LD, 65 (28.6%) had early localized infections, 67 (29.5%) had early disseminated infections, 26 (11.5%) had late LD, 61 (26.9%) had evidence of old infections, and 8 (3.5%) had posttreatment LD syndrome (Fig. 1). Due to lack of complete serologic data, two cases of early localized infection and 6 cases of early disseminated infection were excluded (Table 2). Of the remaining 63 patients with early localized disease, 16 (25.4%) were positive by MTTT but negative by STTT (Table 2). The MTTT identified an additional four (6.6%) cases of early disseminated infection and one case (3.8%) in late LD. The latter was likely an infection due to a European species of Borrelia that required supplemental testing using different IBs. This patient’s exposure was in southern Sweden, and serological testing determined it to be Borrelia afzelii.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of cases by serological result and stage of disease

| Stage | Clinical presentation | No. with laboratory results showing: |

Totala | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCS/C6 EIA+ only | WCS/C6 EIA+, IgM IB+, IgG IB− | WCS/C6 EIA+, IgM IB+, IgG IB+ | WCS/C6 EIA+, IgM IB−, IgG IB+ | |||

| Early localized LD | 16 | 29 | 14 | 4 | 63 | |

| Early disseminated LDc | Multiple EM | 0 | 15 | 19 | 6 | 40 |

| ILI | 0 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 10 | |

| Bell’s palsy | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 9 | |

| Heart block | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| Neuropathy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Meningitis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Late LD | Arthritis | 0 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 24 |

| Complex pain syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Neuropathy | 1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

Excludes 8 cases not tested or without IgM/IgG results (2 early localized LD; 6 early disseminated LD).

European genospecies. LD outside the United States and Canada is often caused by different genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato.

n = 61; 8 patients had more than one clinical presentation at the time of diagnosis.

Concordant positive results between MTTT and immunoblots.

According to our testing algorithm, all specimens with positive IgM or IgG IBs were also positive in the WCS and C6 EIAs (Table 2). There were 49 patients with positive WCS and C6 EIAs with a positive IgM IB but a negative IgG IB. Of these, 29 had early localized and 20 had early disseminated infections (Table 2). The proportion of patients with positive IgG IBs increased with the stage of infection: 29% (18/63) with early localized infections, 74% (45/61) with early disseminated infections, and 96% (25/26) with late LD. If the one case of late disseminated neuropathy caused by a European strain of B. burgdorferi is excluded, all cases of late LD had a positive IgG IB.

Comparison of serologic profiles in patients with and without chart reviews.

Of the 176 patients with charts that could not be reviewed, 51 (29%) had positive WCS and C6 EIAs with negative IgM and IgG IBs, 33 (19%) were positive in both EIAs and IgM IB (but negative in the IgG IB), and 89 (51%) had positive IgG IBs. This distribution was not significantly different from that of patients whose charts were reviewed (21 [9%] had a negative IgM/IgG IB [P = 0.18]; 49 [22%] had a positive IgM IB and a negative IgG IB [P = 0.51]; 156 [69%] had a positive IgG IB [P = 0.96]).

Modeling the specificity of the MTTT algorithm.

The sensitivity of the MTTT algorithm could not be accurately assessed, given that chart reviews were not performed on patients with negative WCS and C6 EIA results (Fig. 1). Therefore, the data obtained in this study were modeled using sensitivity calculations for various MTTT approaches reported in the literature (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

With the number of true positives available from the chart review, using an estimated sensitivity based on published studies, the number of false negatives could be calculated, which in turn was subtracted from the total number of negatives (see Table S1). Compared to patients whose charts were reviewed, the specificity of the MTTT algorithm was 99.5% or 99.6% (CI = 99.4% to 99.7%), regardless of which sensitivity value was used (see Table S1). As a worst case and unlikely scenario, if all of the whole-cell and C6 EIA-positive results in patients with negative IgG IBs were considered false-positive results, the specificity of the MTTT algorithm would remain high at 98.7% (CI = 98.5% to 98.9%) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that a WCS EIA followed by a C6 EIA detected 25% more early B. burgdorferi infections but maintained high specificity that was equivalent to that of the traditional STTT algorithm. The performance characteristics of LD serology depend on the tests used. First-generation EIAs that used WCS of laboratory-adapted B. burgdorferi strains had poor specificity. This, combined with early problems of intralaboratory variability and precision, led to the recommendation of using IB supplemental testing to ensure accuracy (11, 14, 15, 19, 22, 23). Subsequently, second-generation EIAs have been developed using synthetic peptides mimicking conserved epitopes of different B. burgdorferi strains, such as the C6 peptide, VlsE, and the C10 peptide (13, 14). While they improve specificity compared to the WCS, none achieve the specificity of STTT when used alone. Thus, their use as a stand-alone assay for LD diagnosis is not recommended, and the requirement for supplemental testing using IB remains (12, 24). Despite high sensitivity in late disease, the sensitivity of STTT remains poor in early infection (11); turnaround times can be long; and cross-reactivity has been reported in patients with other infections, such as mononucleosis and syphilis (14, 15, 19, 23, 25, 26). A modified algorithm using two EIAs sequentially (i.e., MTTT) has been suggested as an alternative to improve sensitivity for detection of early infections and to shorten turnaround times for results.

This study is the first in Canada evaluating an MTTT algorithm. Recent studies have revealed significant biodiversity among strains of B. burgdorferi identified from vector ticks in many regions in Canada, including Nova Scotia (27). Given that strain diversity can affect the performance of diagnostic tests (28), it is important that the present study was performed in Atlantic Canada to determine the performance of the MTTT in a region where potentially unique strains of B. burgdorferi circulate. Our results are similar to those of studies conducted in the United States (18, 19, 29, 30). The first MTTT algorithm evaluated used WCS EIA followed by C6 EIA and compared its performance to that of STTT using well-characterized sera from patients with LD. Overall, MTTT identified more cases of early LD (61% versus 48%), was more specific than the C6 EIA alone (99.5% versus 98.4%), and had specificity (99.5%) equal to that of STTT (18). Using the same MTTT algorithm compared to STTT, similar specificity and improved sensitivity were observed using samples from the CDC Lyme Serum Repository (29, 30). There are also data to suggest this MTTT algorithm is an acceptable option in pediatric patients (31, 32). However, in one study, the specificity of the WCS/C6 MTTT was found to be lower than that of STTT (96.5% versus 98.8%) in a “symptomatic control group,” which the authors suggest may reflect false-negative STTT in children with early infection (31).

A study comparing the performances of three different MTTTs in 50 patients presenting with physician-diagnosed EM found that MTTT consisting of VlsE EIA followed by C6 EIA was more sensitive than WCS/VlsE or WCS/C6 MTTT in patients with acute EM (19). This difference was not apparent when the same three MTTTs were tested using serum samples from the CDC Lyme Serum Repository, where the sensitivities for the acute phase were 50%, 55%, and 58% and those of convalescent-phase samples were 75%, 79%, and 76%, respectively. The authors hypothesized that the difference might be attributed to the different commercial WCS EIAs used (23). Despite these slight differences in sensitivity, the three MTTT algorithms in both studies were more sensitive and had specificity equivalent to that of STTT (19, 23). Recently, the FDA approved the first MTTT algorithm for the serologic diagnosis of LD. Using a panel of well-characterized serum samples from the CDC, an MTTT algorithm consisting of VlsE/C10 EIA followed by two versions of WCS identified 23% to 27% more acute B. burgdorferi infections than the STTT (16, 21). Our data are consistent with these findings (Table 2).

Although an improvement over STTT, limitations of MTTT remain. MTTT does not distinguish between active and past infections, and as antibody responses can persist for months to years, the difficulty in diagnosing new LD infections in previously infected individuals remains (33). Although better than STTT for detecting early cases of LD, the sensitivity of MTTT is still less than 70%, which means that patients who present with EM should still be treated for early infection rather than relying on serologic testing. The primary advantage of MTTT is the ability for a shorter turnaround time, as both EIAs can be performed in any clinical laboratory with the capability to do serology (rather than at a referral laboratory), and MTTT is more cost-effective than STTT (20). In addition, MTTT may have the benefit of improved sensitivity in identifying positive cases in patients infected with related strains of Borrelia. Although there was only a single case of infection with a European genospecies of Borrelia in our cohort, it was detected by MTTT, whereas it would have been missed by STTT. The reduced sensitivity of STTT in the United States to detect Lyme disease infections acquired in Europe has been described previously (34). However, testing more patients infected with European strains of Borrelia is required to confirm this observation.

The patient population being tested must also be considered when making changes to serologic testing. There are no published data on how many LD serologic tests are performed annually in Canada. A survey of seven large commercial laboratories estimated approximately 3.4 million tests were done on 2.5 million specimens in the United States in 2008 (35). Given that it is estimated that there are approximately 300,000 cases of LD each year in the United States (36), it is likely that a substantial number of these tests are being done on individuals with a low pretest probability for LD, and a similar pattern is likely occurring in Canada. Although the specificities of MTTT are high, even small changes in specificity can substantially reduce the positive predictive value in settings with a low prevalence of LD, where false positives are more likely (18, 37). The current study was done in a region of Canada with some of the highest rates of LD. Whether the predictive value of MTTT would be sufficient in areas of lower prevalence or whether the increased specificity provided by IBs is necessary for optimal results requires further study. Given that most EIAs are polyvalent and measure both IgM and IgG antibodies, there is a theoretical concern about false positives based on the IgM component of the assay (38, 39). As such, there may be instances where identifying a specific IgG response will be helpful if there is ongoing diagnostic uncertainty, such as cases of arthritis. Finally, despite some data to suggest that the order of any of the assays used in the MTTT algorithm could be reversed while maintaining equivalent sensitivity and specificity (19), others have suggested that more data are required to better understand the optimal sequence of the tests used in the MTTT algorithm (23).

This study has limitations. Like all chart reviews, the written description of the patient’s signs and symptoms may not have been entirely accurate, and documentation of all symptoms was not present. In addition, only charts of patients with positive WCS and C6 assays were reviewed. While MTTT was able to detect 25% more cases of early infection than STTT, the charts of patients with negative first-step WCS or those with positive WCS but negative C6 assays were not reviewed, preventing assessment of MTTT sensitivity. Although the sensitivity of the C6 assay for early infection is comparable to that of WCS, the C6 peptide elicits primarily an IgG response (13), which could reduce the ability to detect early infection when it is used as the second EIA in the MTTT algorithm. The STTT algorithm used by our laboratory employed two EIAs as the first step in the algorithm, which may have increased the pretest likelihood that positive specimens would be true positives compared to samples that were positive by the WCS assay alone. While this could have increased the specificity of the STTT further, it is unlikely to have impacted the sensitivity, based on previous studies (29, 30). However, using sensitivities reported in the literature, this study shows that the specificity of MTTT in patients for whom chart reviews were performed remained consistent at 99.5%. However, even among patients with positive EIAs, not all charts were available for review, and the number of false positives from these data could not be assessed. Of patients with charts that could not be reviewed, 51% had positive IgG IBs, suggesting they were true LD cases. In the worst-case scenario, if all the patients without chart review who had positive WCS/C6 EIA results but negative IgG IBs were considered false positives, the specificity of MTTT would remain high at 98.7%. Finally, it is possible that some of the false-positive cases could be due to other medical conditions or infections, such as syphilis, or caused by Epstein-Barr virus, which are known to cause false-positive reactions in Lyme disease EIAs (15, 26); however, there are no clinical data from the chart review to verify this hypothesis, and the serum samples were not available for further testing.

Conclusion.

Consistent with data from the United States, MTTT in this Canadian study detected 25% more acute cases of B. burgdorferi infection than STTT. This is the first study in Canada to demonstrate that MTTT has improved sensitivity over STTT while retaining excellent specificity. The use of MTTT would shorten turnaround times, potentially resulting in more prompt treatment, and may result in overall cost savings, making this an attractive option to implement in the Nova Scotia population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the technologists in the Division of Microbiology who completed the original diagnostic testing and the data entry staff, as well as staff from the NML who conducted the IB testing, including Leanne Scharikow, Courtney Loomer, Alexandre Gilbert, and Brynn Mistafa, and finally, all of the family physicians who collaborated with the study team.

We report no conflicts of interest, with the following exceptions: J. J. LeBlanc has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Merck for projects unrelated to Lyme disease; S. A. McNeil has received a grant and fees from GSK unrelated to Lyme disease; T. F. Hatchette has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer for projects unrelated to Lyme disease and is involved in Lyme disease-related work in his capacities as President of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada, as provincial cochair for the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network Lyme disease diagnostic working group, and as a member of the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network; and L. R. Lindsay is federal cochair of the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network Lyme disease diagnostic working group.

T. F. Hatchette received grant funding from the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Fund to conduct this study.

The study was conceived by T.F.H. and L.R.L. We were all involved in collecting and analyzing the data. Laboratory data and analysis were provided by T.F.H., J.J.L., L.R.L., K.B., and A.D. Chart reviews, and analysis of the clinical data were conducted by I.R.C.D., S.A.M., W.A., and T.F.H. D.M.-C. coordinated the statistical analysis and data management. I.R.C.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. We all reviewed and revised the manuscript and agreed to its publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. 14 August 2018. Surveillance of Lyme disease. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme-disease/surveillance-lyme-disease.html. 18 September 2019, access date.

- 2.Gasmi S, Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Burns S, Fleming S, Badcock J, Hanan S, Gaulin C, Leblanc MA, Russell C, Nelder M, Hobbs L, Graham-Derham S, Lachance L, Scott AN, Galanis E, Koffi JK. 2017. Surveillance for Lyme disease in Canada: 2009–2015. Can Commun Dis Rep 43:194–199. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v43i10a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry B, Roth D, Reilly R, MacDougall L, Mak S, Li M, Muhamad M. 2011. How big is the Lyme problem? Using novel methods to estimate the true number of Lyme disease cases in British Columbia residents from 1997 to 2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 11:863–868. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden NH, Bouchard C, Badcock J, Drebot MA, Elias SP, Hatchette TF, Koffi JK, Leighton PA, Lindsay LR, Lubelczyk CB, Peregrine AS, Smith RP, Webster D. 2019. What is the real number of Lyme disease cases in Canada? BMC Public Health 19:849. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leighton PA, Koffi KJ, Pelcat Y, Lindsay LR, Ogden NH. 2012. Predicting the speed of tick invasion: an empirical model of range expansion for the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada. J Appl Ecol 49:457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02112.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon JA, Marrotte RR, Desrosiers N, Fiset J, Gaitan J, Gonzalez A, Koffi JK, Lapointe FJ, Leighton PA, Lindsay LR, Logan T, Milord F, Ogden NH, Rogic A, Roy-Dufresne E, Suter D, Tessier N, Millien V. 2014. Climate change and habitat fragmentation drive the occurrence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease, at the northeastern limit of its distribution. Evol Appl 7:750–764. doi: 10.1111/eva.12165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatchette TF, Johnston BL, Schleihauf E, Mask A, Haldane D, Drebot M, Baikie M, Cole T, Fleming S, Gould R, Lindsay R. 2015. Epidemiology of Lyme disease, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2002–2003. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1751–1758. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. 17 January 2020. Population health assessment and surveillance. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/populationhealth/. 7 August 2019. access date.

- 9.Shapiro ED. 2014. Clinical practice. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 370:1724–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1314325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatchette TF, Davis I, Johnston BL. 2014. Lyme disease: clinical diagnosis and treatment. Can Commun Dis Rep 40:194–208. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v40i11a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waddell LA, Greig J, Mascarenhas M, Harding S, Lindsay R, Ogden N. 2016. The accuracy of diagnostic tests for Lyme disease in humans, a systematic review and meta-analysis of North American research. PLoS One 11:e0168613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, Krause PJ, Bakken JS, Strle F, Stanek G, Bockenstedt L, Fish D, Dumler JS, Nadelman RB. 2006. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 43:1089–1134. doi: 10.1086/508667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theel ES. 2016. The past, present, and (possible) future of serologic testing for Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol 54:1191–1196. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03394-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branda JA, Body BA, Boyle J, Branson BM, Dattwyler RJ, Fikrig E, Gerald NJ, Gomes-Solecki M, Kintrup M, Ledizet M, Levin AE, Lewinski M, Liotta LA, Marques A, Mead PS, Mongodin EF, Pillai S, Rao P, Robinson WH, Roth KM, Schriefer ME, Slezak T, Snyder J, Steere AC, Witkowski J, Wong SJ, Schutzer SE. 2018. Advances in serodiagnostic testing for Lyme disease are at hand. Clin Infect Dis 66:1133–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore A, Nelson C, Molins C, Mead P, Schriefer M. 2016. Current guidelines, common clinical pitfalls, and future directions for laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1169–1177. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.151694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. 29 July 2019. FDA clears new indications for existing Lyme disease tests that may help streamline diagnoses. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-clears-new-indications-existing-lyme-disease-tests-may-help-streamline-diagnoses. 21 August 2019, access date.

- 17.Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. 2019. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:703. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branda JA, Linskey K, Kim YA, Steere AC, Ferraro MJ. 2011. Two-tiered antibody testing for Lyme disease with use of 2 enzyme immunoassays, a whole-cell sonicate enzyme immunoassay followed by a VlsE C6 peptide enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis 53:541–547. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branda JA, Strle K, Nigrovic LE, Lantos PM, Lepore TJ, Damle NS, Ferraro MJ, Steere AC. 2017. Evaluation of modified 2-tiered serodiagnostic testing algorithms for early Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 64:1074–1080. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wormser GP, Levin A, Soman S, Adenikinju O, Longo MV, Branda JA. 2013. Comparative cost-effectiveness of two-tiered testing strategies for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease with noncutaneous manifestations. J Clin Microbiol 51:4045–4049. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01853-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeus Scientific. Clinical data. 21 August 2019, access date. https://www.zeusscientific.com/clinical-data.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1995. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 44:590–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pegalajar-Jurado A, Schriefer ME, Welch RJ, Couturier MR, MacKenzie T, Clark RJ, Ashton LV, Delorey MJ, Molins CR. 2018. Evaluation of modified two-tiered testing algorithms for Lyme disease laboratory diagnosis using well-characterized serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01943-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01943-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 11 April 2018. Lyme disease. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng95. [PubMed]

- 25.Lindsay LR, Bernat K, Dibernardo A. 2014. Laboratory diagnostics for Lyme disease. Can Commun Dis Rep 40:209–217. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v40i11a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patriquin G, LeBlanc J, Heinstein C, Roberts C, Lindsay R, Hatchette TF. 2016. Cross-reactivity between Lyme and syphilis screening assays: Lyme disease does not cause false-positive syphilis screens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 84:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mechai S, Margos G, Feil EJ, Lindsay LR, Ogden NH. 2015. Complex population structure of Borrelia burgdorferi in southeastern and south central Canada as revealed by phylogeographic analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:1309–1318. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03730-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wormser GP, Liveris D, Hanincová K, Brisson D, Ludin S, Stracuzzi VJ, Embers ME, Philipp MT, Levin A, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Schwartz I. 2008. Effect of Borrelia burgdorferi genotype on the sensitivity of C6 and 2-tier testing in North American patients with culture-confirmed Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 47:910–914. doi: 10.1086/591529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molins CR, Sexton C, Young JW, Ashton LV, Pappert R, Beard CB, Schriefer ME. 2014. Collection and characterization of samples for establishment of a serum repository for Lyme disease diagnostic test development and evaluation. J Clin Microbiol 52:3755–3762. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01409-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molins CR, Delorey MJ, Sexton C, Schriefer ME. 2016. Lyme borreliosis serology: performance of several commonly used laboratory diagnostic tests and a large resource panel of well-characterized patient samples. J Clin Microbiol 54:2726–2734. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00874-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipsett SC, Branda JA, McAdam AJ, Vernacchio L, Gordon CD, Gordon CR, Nigrovic LE. 2016. Evaluation of the C6 Lyme enzyme immunoassay for the diagnosis of Lyme disease in children and adolescents. Clin Infect Dis 63:922–928. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipsett SC, Branda JA, Nigrovic LE. 2019. Evaluation of the modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) method for the diagnosis of Lyme disease in children. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00547-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00547-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalish RA, McHugh G, Granquist J, Shea B, Ruthazer R, Steere AC. 2001. Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10–20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 33:780–785. doi: 10.1086/322669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branda JA, Strle F, Strle K, Sikand N, Ferraro MJ, Steere AC. 2013. Performance of United States serologic assays in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis acquired in Europe. Clin Infect Dis 57:333–340. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinckley AF, Connally NP, Meek JI, Johnson BJ, Kemperman MM, Feldman KA, White JL, Mead PS. 2014. Lyme disease testing by large commercial laboratories in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 59:676–681. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuehn BM. 2013. CDC estimates 300000 US cases of Lyme disease annually. JAMA 310:1110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lantos PM, Branda JA, Boggan JC, Chudgar SM, Wilson EA, Ruffin F, Fowler V, Auwaerter PG, Nigrovic LE. 2015. Poor positive predictive value of Lyme disease serologic testing in an area of low disease incidence. Clin Infect Dis 61:1374–1380. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber BJ, Burganowski RP, Colton L, Escobar JD, Pathak SR, Gambino-Shirley KJ. 2019. Lyme disease overdiagnosis in a large healthcare system: a population-based, retrospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seriburi V, Ndukwe N, Chang Z, Cox ME, Wormser GP. 2012. High frequency of false positive IgM immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.