Abstract

Cryptosporidium is a ubiquitous protozoan in human and animals. To investigate the genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. in alpaca (Vicugna pacos) in China, 484 fecal samples from alpacas were collected at nine sites, and Cryptosporidium spp. were screened with PCR amplification of the small subunit ribosome RNA (SSU rRNA) locus. Cryptosporidium spp. infected 2.9% (14/484) of the alpacas. Of the nine collection sites, two were positive for Cryptosporidium, Wensu (3.0%, 3/100) and Qinghe (31.4%, 11/35). Three Cryptosporidium species were identified: C. parvum (n = 2), C. ubiquitum (n = 1), and C. occultus (n = 11). Cryptosporidium parvum and C. ubiquitum were further subtyped with the 60-kDa glycoprotein locus (gp60). The two C. parvum isolates were subtype IIdA15G1, but the one C. ubiquitum isolate was not subtyped successfully. A phylogenetic analysis indicated that the Cryptosporidium isolates clustered with previously identified species. To our knowledge, this is the first report of Cryptosporidium infections in alpacas in China and provides baseline data for the study of Cryptosporidium in alpacas in China.

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, Molecular identification, Alpaca, China

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First report of Cryptosporidium spp. infections (with 2.9%) in alpacas in China.

-

•

Three zoonotic Cryptosporidium species were identified in alpacas.

-

•

It provides the molecular characteristic data for the study of Cryptosporidium in alpacas.

1. Introduction

Cryptosporidium is a ubiquitous apicomplexan parasite that mainly infects the gastrointestinal epithelium of a wide range of human and animal hosts (Checkley et al., 2015; Ryan et al., 2018). Cryptosporidium infections are recognized as one of the major causes of moderate to severe diarrhea in developing countries (Ryan et al., 2014). The pathogenicity of Cryptosporidium infection varies with the species of parasite involved and the type, age, and immune status of the host (Thomson et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2018). At least 38 Cryptosporidium species have been identified, and zoonotic Cryptosporidium infections play an important role in both developed and developing countries (Xiao, 2010; Feng et al., 2018). Since the first report of Cryptosporidium spp. infections in young alpacas in 1998 (Bidewell and Cattell, 1998), cryptosporidiosis has been recognized as a common cause of diarrhea in young (preweaned) alpacas (Starkey et al., 2007; Waitt et al., 2008).

Several studies have demonstrated natural infections of Cryptosporidium spp. in South American camelids, including alpacas (Vicugna pacos), llamas (Lama glama), and guanacos (L. guanicoe) in the past decades (Rulofson et al., 2001; Whitehead and Anderson, 2006; Waitt et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012; Koehler et al., 2018). One cryptosporidiosis outbreak among alpacas caused by C. parvum involved six alpaca crias from a single farm, and importantly, three people involved in caring for the crias on that farm were subsequently diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis (Starkey et al., 2007). Another study demonstrated that not only can older weaned alpacas succumb to severe clinical cryptosporidiosis attributable to C. parvum, but that these animals can act as potential sources of zoonotic infection (Wessels et al., 2013).

Alpacas were originated on the American continent and were imported onto the Chinese mainland from Australia in 2002 (Zhang et al., 2019). As of today, alpacas are raised on farms in Shanxi Province, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Shandong Province, Beijing City and some other areas for both meat and wool, and in some zoological gardens for the tourist industry in China. It was reported that there are estimated to be between 5000 and 10,000 alpacas in China in 2018. Cryptosporidium infections have been recoded in alpacas in UK, US, Peru, Australia, etc. (Twomey et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2012; Koehler et al., 2018; Gomez-Puerta et al., 2020). However, there has been no study of Cryptosporidium infections in alpacas in China. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and molecular characteristics of Cryptosporidium spp. in alpacas in China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics approval

Appropriate permission was obtained from the herd owners or managers before the alpaca fecal samples were collected, and no specific permit was required for field studies. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tarim University (Xinjiang, China).

2.2. Sample collection

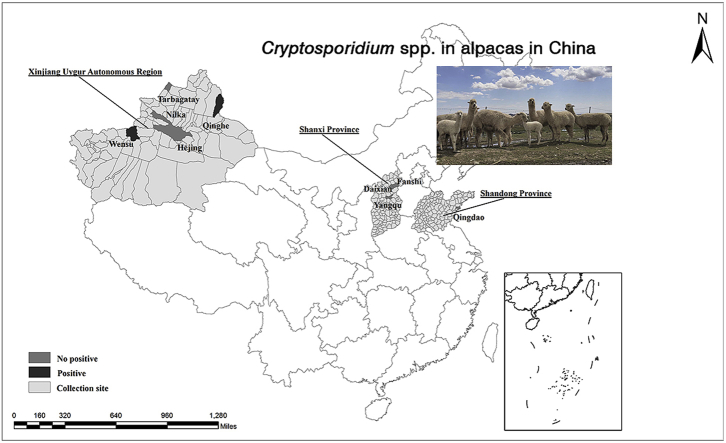

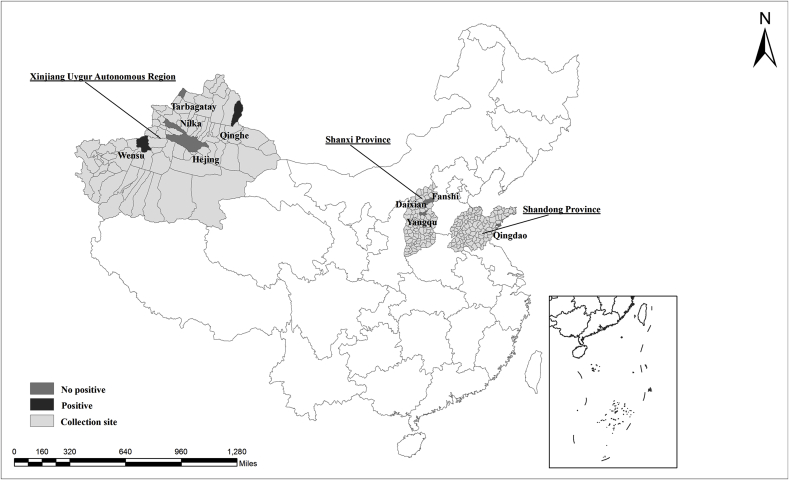

Between August 2016 and March 2017 and between May and August 2019, a total of 484 fresh fecal samples were collected from individual alpacas at nine sites in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Tacheng, Wensu, Hejing, Qinghe, and Nilka), Shanxi Province (Fanshi, Daixian, and Yangqu), and Shandong Province (Qingdao) (Fig. 1). All the alpacas grazed freely on hay in a fenced pasture during the daytime, and had shelter at night. The alpacas were original imported Australia or Netherlands, and followed by breeding by artificial insemination. The collected samples represented approximately 10%–50% of each alpaca herd. The age group of alpacas involving in present study were available roughly, only for adult or younger, and exact of the days/years were not obtained. The adults alpacas involved in present study all were female, and the sex of younger alpacas were not obtained (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Locations of alpaca fecal sampling in China.

Table 1.

Prevalence and species/subtypes of Cryptosporidium in alpacas in China.

| Collection sites | Import from (Year) | Collection time | Number of population | Age group | Number of sampled | Number of positive | Cryptosporidium species/subtypes (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarbagatay | Netherlands (2014) | Aug 2016 | 46 | Adult | 18 | 0 | |

| Wensu | Australia (2014–2015) | Aug 2016 | 390* | Subtotal | 100 | 3 (3.0%) | C. parvum (2)/IIdA15G1 (2); C. ubiquitum (1) |

| Younger | 17 | 0 | |||||

| Adult | 83 | 3 (3.6%) | C. parvum (2)/IIdA15G1 (2); C. ubiquitum (1) | ||||

| Hejing | Australia (2013) | Mar 2017 | 40 | Adult | 20 | 0 | |

| Qinghe | Australia (2004) | Mar 2017 | 95 | Adult | 35 | 11 (31.4%) | C. occultus (11) |

| Nilka | Australia (2005) | Jul 2017 | 38 | Adult | 12 | 0 | |

| Qingdao | Netherlands (2014–2015) | May 2019 | 102 | Adult | 20 | 0 | |

| Fanshi | Australia (2015–2017) | Aug 2019 | 210 | Subtotal | 42 | 0 | |

| Younger | 7 | 0 | |||||

| Adult | 35 | 0 | |||||

| Daixian | Australia (2015–2017) | Aug 2019 | 89 | Subtotal | 38 | 0 | |

| Younger | 11 | 0 | |||||

| Adult | 27 | 0 | |||||

| Yangqu | Australia (2014–2017) | Aug 2019 | 1200* | Subtotal | 199 | 0 | |

| Younger | 5 | 0 | |||||

| Adult | 164 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 2210* | 484 | 14 (2.9%) |

C. occultus (11); C. parvum (2)/IIdA15G1 (2); C. ubiquitum (1) |

*approximate.

Fresh alpaca fecal samples (10–20 g) were collected with sterile gloves and placed in labeled clean plastic bags immediately after defecation. All the collected samples were transported to the testing laboratory in a cooler with ice packs. The samples were stored at 4 °C before DNA extraction, and the DNA was extracted within 1 week of collection. No obvious diarrhea symptoms were observed during sampling.

2.3. DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 200 mg of each fecal sample with the E.Z.N.A.® Stool DNA Kit (Omega Biotek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then 200 μL of elution buffer was added to each DNA sample, and the sample was stored at −20 °C until PCR amplification.

Cryptosporidium spp. were screened with nested PCR amplification of the small subunit ribosome RNA (SSU rRNA) locus, as previously described (Cai et al., 2017). Cryptosporidium parvum and C. ubiquitum were then subgenotyped with an analysis of the 60-kDa glycoprotein locus (gp60) sequence (Alves et al., 2003; Li et al., 2014). The 2×EasyTaq® PCR SuperMix (TransGene Biotech Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) reaction system was used for each PCR. To validate the PCR amplification, positive (chicken -derived C. baileyi DNA) and negative (distilled water without DNA) controls were included in each PCR batch. The secondary PCR products were examined with electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels stained with GelRed™ (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA, USA).

The intensity of Cryptosporidium spp. oocyst shedding was assessed using a SYBR Green-based qPCR of the 18S-LC2 targeting the SSU rRNA locus (Li et al., 2015). The 20 μl qPCR mix consisted of 10 μl of 2×SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (TransGene Biotech Co. Ltd, Beijing, China), 0.5 μl of 20 μM primers (each), 1 μl of DNA and 8 μl of PCR grade water. The qPCR was conducted on a Mastercycler® ep realplex (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) as previously described (Chen et al., 2019). The number of oocysts per gram of feces (OPG) in Cryptosporidium-positive samples was calculated based on the Ct values, using a standard curve generated from spiked with known numbers of oocysts of the C. parvum isolate.

2.4. Sequencing analysis

The positive PCR amplicons of the target loci were sequenced bidirectionally by a commercial sequencing company (GENEWIZ, Suzhou, China). The nucleotide sequences were compared with reference sequences downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using ClustalX 2.1 (http://www.clustal.org/) to identify the Cryptosporidium species and subgenotypes.

2.5. Statistical analysis and nucleotide sequence accession numbers

A χ2 test was used to compare the prevalence of the Cryptosporidium spp. in the alpacas. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The representative nucleotide sequences reported in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession numbers MN876846–MN876848 for the SSU rRNA locus and MN879351 for the gp60 locus.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and distributions of Cryptosporidium spp. in alpacas

A total of 484 alpaca fecal samples were screened for Cryptosporidium spp. with PCR based on the SSU rRNA locus. Cryptosporidium spp. were detected in 2.9% (14/484) of the samples. Of the nine collection sites, two were positive for Cryptosporidium, Qinghe (31.4%, 11/35) and Wensu (3.0%, 3/100), and all the Cryptosporidium-positive samples were identified in adult female alpacas (Table 1).

Sequences analysis identified three Cryptosporidium species: C. parvum (n = 2), C. ubiquitum (n = 1), and C. occultus (n = 11). Cryptosporidium occultus was the predominant species within the positive alpacas (78.6%, 11/14). The number of OPG of one C. ubiquitum-positive samples was 13,121, and the average number of OPG of two C. parvum-positive samples was 16,011 ± 5803, 11 C. occultus -positive samples was 472 ± 526, respectively.

3.2. Sequences analysis and phylogenetic analysis of SSU rRNA

Two SSU C. parvum sequences were identical to isolates from a human (MK990043), dairy cattle (MF074692), sika deer (KX259139), and donkey (KU200953) in China. One C. ubiquitum sequence shared 99.9% homology with that of an isolate from a bactrian camel (MH442993) in China, with one substitution at nucleotide position 83 (T→C). The remaining 11 C. occultus sequences were identical to isolates from a human (HQ822146) in the UK, bamboo rat (MK731963) in China, and rats (MG699176, MG699177, MG699178, and MG699179) in the Czech Republic.

3.3. Subtypes of C. parvum

The C. parvum and C. ubiquitum isolates were subtyped based on a gp60 locus sequence analysis. The two C. parvum isolates were identified as IIdA15G1, and the one C. ubiquitum was not subtyped successfully. The two C. parvum isolates shared 100% nucleotide sequence identity at the gp60 locus with the corresponding regions of C. parvum isolates from humans (JF268648) in India and various animals in China, including dairy cattle (KT964798), macaque (KJ917586), sheep (MH794167), bamboo rat (MK731965), horse (MK770629), and rodents (GQ121027).

4. Discussion

Cryptosporidium spp. are important pathogens causing diarrhea in preweaned alpacas (Cebra et al., 2003; Rojas et al., 2016). The observed Cryptosporidium spp. infection rate in alpacas in China was 2.9% (14/484) in the present study. Slightly higher prevalence rates have been reported in alpacas in Australia (3.7%, 3/81) (Koehler et al., 2018), Peru (4.4%, 12/274) (Gómez-Couso et al., 2012), and America (7.7%, 17/220) (Burton et al., 2012). However, much higher prevalence rates were documented in newborn alpacas in a report from Peru, in which 12.4% of neonatal alpacas were infected (159/1312) (Gomez-Puerta et al., 2020). The different prevalence rates reported in these studies may be attributable to differences in the feeding sites, age distributions, sample sizes, host health status, management systems, and population densities of the animals tested, as well as some other identified factors. However, the Cryptosporidium-positive were not observed in younger alpacas in present study, a further study is required to investigate the relationships between Cryptosporidium infections and the age of alpacas in China.

Three zoonotic Cryptosporidium species (C. parvum, C. cuniculus, and C. ubiquitum) have been reported in alpacas in previous studies (Koehler et al., 2018; Gomez-Puerta et al., 2020). In the present study, three Cryptosporidium species, C. parvum, C. ubiquitum, and C. occultus, were identified in alpacas (Table 1). To our knowledge, this is the first report of C. occultus infection in alpacas. Cryptosporidium parvum, C. ubiquitum, and C. occultus have extensive host ranges, which include humans, ruminants, and rodents, in various countries (Kváč et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Cryptosporidium parvum has been predominantly reported in alpacas, and was the only species detected in 153 Cryptosporidium-infected newborn alpaca as in a study in Peru (Gomez-Puerta et al., 2020). Cryptosporidium ubiquitum appears to be the most common Cryptosporidium species infecting humans and ruminants in China, especially sheep (Mi et al., 2018). Cryptosporidium occultus, previously known as the C. suis-like genotype, has been identified in humans, cattle, yaks, and rats, which suggests that it has a wide host range (Kváč et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018).

In this study, we detected C. parvum subtype IIdA15G1, which is commonly found in humans and animals (yaks, buffalos, rodents, and calves) in China (Feng and Xiao, 2017). Subtype IIdA15G1 was responsible for an outbreak of lethal cryptosporidiosis in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of preweaned calves following severe diarrhea (Cui et al., 2014). However, an alpaca-derived C. parvum isolated in Canada was subtype IIa (n = 1) (O'Brien et al., 2008), and one isolated in Australia was subtype IIaA20G3R1 (n = 1) (Koehler et al., 2018). These results indicate that there are genetic differences in the subtypes of C. parvum infecting alpacas in different regions.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first report of Cryptosporidium spp. in alpaca in China. Three Cryptosporidium species (C. parvum, C. ubiquitum, and C. occultus) were identified, and this is also the first report of C. occultus infections in alpacas. It provides the basic data of molecular characteristic for the study of Cryptosporidium in animals in China.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31702227), the Program for Young and Middle-aged Leading Science, Technology, and Innovation of Xinjiang Production & Construction Group (2018CB034), and Key Technologies R & D Programme of Xinjiang Production & Construction Group (2020AB025). We thank Janine Miller, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Editing China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

References

- Alves M., Xiao L., Sulaiman I., Lal A.A., Matos O., Antunes F. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:2744–2747. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2744-2747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidewell C.A., Cattell J.H. Cryptosporidiosis in young alpacas. Vet. Rec. 1998;142(11):287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton A.J., Nydam D.V., Mitchell K.J., Bowman D.D. Fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium oocysts in healthy alpaca crias and their dams. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2012;241(4):496–498. doi: 10.2460/javma.241.4.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Guo Y., Pan B., Li N., Wang X., Tang C., Feng Y., Xiao L. Longitudinal monitoring of Cryptosporidium species in pre-weaned dairy calves on five farms in Shanghai, China. Vet. Parasitol. 2017;241:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebra C.K., Mattson D.E., Baker R.J., Sonn R.J., Dearing P.L. Potential pathogens in feces from unweaned llamas and alpacas with diarrhea. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003;223(12):1806–1808. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.223.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkley W., White A.C., Jr., Jaganath D., Arrowood M.J., Chalmers R.M., Chen X.M., Fayer R., Griffiths J.K., Guerrant R.L., Hedstrom L., Huston C.D., Kotloff K.L., Kang G., Mead J.R., Miller M., Petri W.A., Jr., Priest J.W., Roos D.S., Striepen B., Thompson R.C., Ward H.D., Van Voorhis W.A., Xiao L., Zhu G., Houpt E.R. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015;15(1):85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Hu S., Jiang W., Zhao J., Li N., Guo Y., Liao C., Han Q., Feng Y., Xiao L. Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes in crab-eating macaques. Parasites Vectors. 2019;12(1):350. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3604-7. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z., Wang R., Huang J., Wang H., Zhao J., Luo N., Li J., Zhang Z., Zhang L. Cryptosporidiosis caused by Cryptosporidium parvum subtype IIdA15G1 at a dairy farm in Northwestern China. Parasites Vectors. 2014;7:529. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0529-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in China. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1701. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Ryan U.M., Xiao L. Genetic diversity and population structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34(11):997–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Couso H., Ortega-Mora L.M., Aguado-Martínez A., Rosadio-Alcántara R., Maturrano-Hernández L., Luna-Espinoza L., Zanabria-Huisa V., Pedraza-Díaz S. Presence and molecular characterisation of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in alpacas (Vicugna pacos) from Peru. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;187(3-4):414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Puerta L.A., Gonzalez A.E., Vargas-Calla A., Lopez-Urbina M.T., Cama V., Xiao L. Cryptosporidium parvum as a risk factor of diarrhea occurrence in neonatal alpacas in Peru. Parasitol. Res. 2020;119(1):243–248. doi: 10.1007/s00436-019-06468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Zhang Z., Zhang Y., Yang Y., Zhao J., Wang R., Jian F., Ning C., Zhang W., Zhang L. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in deer in Henan and Jilin, China. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2813-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler A.V., Rashid M.H., Zhang Y., Vaughan J.L., Gasser R.B., Jabbar A. First cross-sectional, molecular epidemiological survey of Cryptosporidium, Giardia and Enterocytozoon in alpaca (Vicugna pacos) in Australia. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):498. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3055-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M., Vlnatá G., Ježková J., Horčičková M., Konečný R., Hlásková L., McEvoy J., Sak B. Cryptosporidium occultus sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in rats. Eur. J. Protistol. 2018;63:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Xiao L., Alderisio K., Elwin K., Cebelinski E., Chalmers R., Santin M., Fayer R., Kvac M., Ryan U., Sak B., Stanko M., Guo Y., Wang L., Zhang L., Cai J., Roellig D., Feng Y. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20(2):217–224. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.121797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Neumann N.F., Ruecker N., Alderisio K.A., Sturbaum G.D., Villegas E.N., Chalmers R., Monis P., Feng Y., Xiao L. Development and evaluation of three real-time PCR assays for genotyping and source tracking Cryptosporidium spp. in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81(17):5845–5854. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01699-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi R., Wang X., Huang Y., Mu G., Zhang Y., Jia H., Zhang X., Yang H., Wang X., Han X., Chen Z. Sheep as a potential source of zoonotic cryptosporidiosis in China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84(18) doi: 10.1128/AEM.00868-18. pii:e00868-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien E., McInnes L., Ryan U. Cryptosporidium GP60 genotypes from humans and domesticated animals in Australia, North America and Europe. Exp. Parasitol. 2008;118(1):118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M., Manchego A., Rocha C.B., Fornells L.A., Silva R.C., Mendes G.S., Dias H.G., Sandoval N., Pezo D., Santos N. Outbreak of diarrhea among preweaning alpacas (Vicugna pacos) in the southern Peruvian highland. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2016;10(3):269–274. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulofson F.C., Atwill E.R., Holmberg C.A. Fecal shedding of Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium parvum, Salmonella organisms, and Escherichia coli O157:H7 from llamas in California. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2001;62(4):637–642. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U., Fayer R., Xiao L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitology. 2014;141(13):1667–1685. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U., Hijjawi N., Xiao L. Foodborne cryptosporidiosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey S.R., Johnson A.L., Ziegler P.E., Mohammed H.O. An outbreak of cryptosporidiosis among alpaca crias and their human caregivers. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2007;231(10):1562–1567. doi: 10.2460/javma.231.10.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S., Hamilton C.A., Hope J.C., Katzer F., Mabbott N.A., Morrison L.J., Innes E.A. Bovine cryptosporidiosis: impact, host-parasite interaction and control strategies. Vet. Res. 2017;48(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0447-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey D.F., Barlow A.M., Bell S., Chalmers R.M., Elwin K., Giles M., Higgins R.J., Robinson G., Stringer R.M. Cryptosporidiosis in two alpaca (Lama pacos) holdings in the South-West of England. Vet. J. 2008;175(3):419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitt L.H., Cebra C.K., Firshman A.M., McKenzie E.C., Schlipf J.W., Jr. Cryptosporidiosis in 20 alpaca crias. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008;233(2):294–298. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels J., Wessels M., Featherstone C., Pike R. Cryptosporidiosis in eight-month-old weaned alpacas. Vet. Rec. 2013;173(17):426–427. doi: 10.1136/vr.f6395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead C.E., Anderson D.E. Neonatal diarrhea in llamas and alpacas. Small Rumin. Res. 2006;61:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;124(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Wang H., Zhao A., Zhao W., Wei Z., Li Z., Qi M. Molecular detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in alpacas (Vicugna pacos) in Xinjiang, China. Parasite. 2019;26:31. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2019031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Wang J., Ren G., Yang Z., Yang F., Zhang W., Xu Y., Liu A., Ling H. Molecular characterizations of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) from Heilongjiang Province, China. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):313. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]