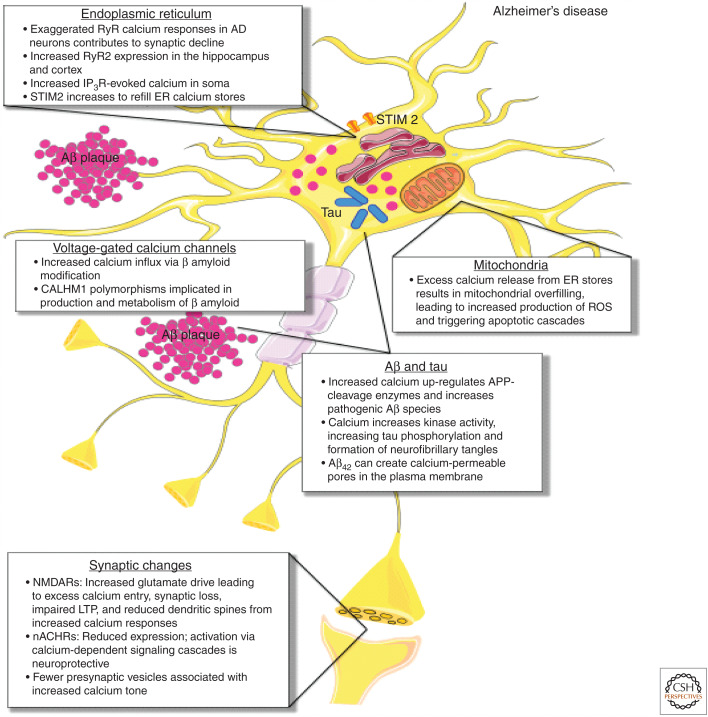

Figure 1.

Calcium-handling defects in Alzheimer's disease (AD). In AD, exaggerated ryanodine receptor (RyR) calcium responses in AD neurons contribute to synaptic decline, with increased RyR2 expression seen in the hippocampus and cortex. Increased inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-evoked calcium is seen in the soma, and stromal interaction molecule 2 (STIM2) expression and activation increases to refill ER calcium stores. As a result of excess calcium release from ER stores, mitochondrial calcium overload occurs, leading to metabolic dysfunction, increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and apoptotic engagement. Increased calcium also up-regulates APP-cleavage enzymes and increases pathogenic β-amyloid species. Aβ42 in particular can create calcium-permeable pores in the plasma membrane, contributing to calcium dysregulation. β-amyloid modification also increases calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). Increased cytosolic calcium enhances the activity of kinases that phosphorylate tau, leading to increased tau phosphorylation and ultimately the formation of neurofibrillary tangles. At the synapse, expression of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nACHRs) is reduced through neuronal loss, while activation of nACHRs via calcium-dependent signaling cascades that are neuroprotective. Increased glutamate drive on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) leads to excess calcium entry, synaptic loss, and impaired long-term potentiation (LTP), and reduced dendritic spines from increased calcium responses. Fewer presynaptic vesicles result in increased calcium tone at terminals.