Abstract

Photoremovable caging groups are useful for biological applications since the deprotection process can be initiated by illumination with light without the necessity of adding additional reagents such as acids or bases that can perturb biological activity. In solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), the most common photoremovable group used for thiol protection is the o-nitrobenzyl group and related analogues. In earlier work, we explored the use of the nitrodibenzofuran (NDBF) group for thiol protection and found it to exhibit a faster rate towards UV photolysis relative to simple nitroveratryl-based protecting groups and a useful two-photon cross-section. Here we describe the synthesis of a new NDBF-based protecting group bearing a methoxy substituent and use it to prepare a protected form of cysteine suitable for SPPS. This reagent was then used to assemble two biologically relevant peptides and characterize their photolysis kinetics in both UV- and two-photon-mediated reactions; a two-photon action cross-section of 0.71 – 1.4 GM for the new protecting group was particularly notable. Finally, uncaging of these protected peptides by either UV or two-photon activation was used to initiate their subsequent enzymatic processing by the enzyme farnesyltransferase. These experiments highlight the utility of this new protecting group for SPPS and biological experiments.

INTRODUCTION

Thiol groups play key roles in a diverse range of biological processes ranging from acting as active site nucleophiles in enzymatic reactions to participating in disulfide bonds to stabilize protein structure as well as serving as sites for post-translational modifications.1–3 The ability to mask a thiol group with a protecting group allows the resulting “caged” biomolecule to be maintained in an inactive state prior to “uncaging” it by deprotection. Photoremovable caging groups4 are useful for biological applications since the uncaging process can be initiated by illumination with light without the necessity of adding additional reagents such as acids or bases that can perturb biological activity.5,6 Light activated processes are particularly well suited for applications in live cells where it is generally not possible to use reagent-based deprotection conditions due to cellular toxicity.7 Photoremovable protecting groups are also advantageous due to the unique features associated with light activation since uncaging can be triggered with high spatiotemporal control; the specific location and time of deprotection can be controlled by the position and timing of illumination. The spatial precision of uncaging can be improved using two-photon (TP) activation provided the protecting group chromophore manifests a usable TP action cross section; the development of caged neurotransmitters has benefited substantially from this feature.8 TP activation also reduces potential phototoxicity since irradiation is performed at double the wavelength employed for UV excitation, which is in the visible or near IR region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

In solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), a vast number of protecting groups have been developed for cysteine.9 However, for light-mediated deprotection, the most common protecting group used for thiol protection is the o-nitrobenzyl group (NB)10 and related analogues including o-nitroveratryl (NV) (Figure 1).7,11–14 While robust and useful for many applications, such protecting groups do not exhibit useful TP action cross-sections, thus limiting their utility. To circumvent this limitation, several groups have investigated the use of other protecting groups based on coumarin, quinoline and dibenzofuran scaffolds.15–18 Thiol protecting groups based on a coumarin core have been studied and employed for a range of applications.18–21 Protecting groups employing a thioether bond such as Bhc are more stable than those featuring a thiocarbonate linkage (BCMACMOC). However, irradiation of the former is often accompanied by isomerization without photocleavage18,20 while the latter can undergo rearrangement when unprotected thiols or primary amine groups are present within the same peptide.20 In earlier work, we explored the use of the nitrodibenzofuran (NDBF) group for thiol protection and found it to exhibit a faster rate towards UV photolysis relative to simple NV-based protecting groups.18 Moreover, it manifested a useful TP cross-section that could be particularly applicable to biological experiments performed in live cells. Previous work with the NV group suggests that its photochemical properties can be modulated via substitution of the aryl ring.22 Here we describe the synthesis of a new NDBF-based protecting group bearing a methoxy substituent and use it to prepare Fmoc-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1), a building block suitable for SPPS. In the design of this moiety, we elected to preserve the ethyl group used in 2 as the point of thiol linkage (resulting in an additional stereogenic center) since photolysis of such compounds leads to the production of ketone products that have less putative cellular toxicity compared with the aldehyde products that are formed from simpler groups such as NV.23 This reagent was then used to assemble two biologically relevant peptides and characterize their photolysis kinetics in both UV- and TP-mediated reactions. Finally, uncaging of these protected peptides by either UV or TP activation was used to initiate their subsequent enzymatic processing by the enzyme farnesyltransferase. These experiments highlight the utility of this new protecting group for SPPS and biological experiments.

Figure 1.

Representative photoremovable protecting groups used for the protection of the thiol group of cysteine and building blocks suitable for SPPS used here.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthetic Chemistry.

In our earlier work, N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NDBF)-OH (2) was prepared starting from dibenzofuran. For the preparation of N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF-OH) (1), a new, and more general route (Scheme 1), was developed to facilitate the synthesis of substituted dibenzofurans. The precursor, 2-bromo-5-methoxyphenol, containing the desired methoxy group was treated with 4-fluoro-2-nitrobenzaldehyde to yield diarylether 3. Protection of the aldehyde as an acetal followed by palladium-catalyzed aryl coupling and deprotection afforded aldehyde 6 that was then converted to the racemic secondary alcohol, 7, using trimethylaluminum. That alcohol was then activated to the corresponding bromide that was then used to alkylate N-Fmoc-L-cysteine methyl ester under acidic conditions24 to produce the fully protected amino acid 9. Hydrolysis of that ester using trimethyltin hydroxide25 gave N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1), a protected form of cysteine suitable for solid phase peptide synthesis; mild conditions are essential for the hydrolysis of 9 to avoid potential racemization of the protected cysteine residue.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1).

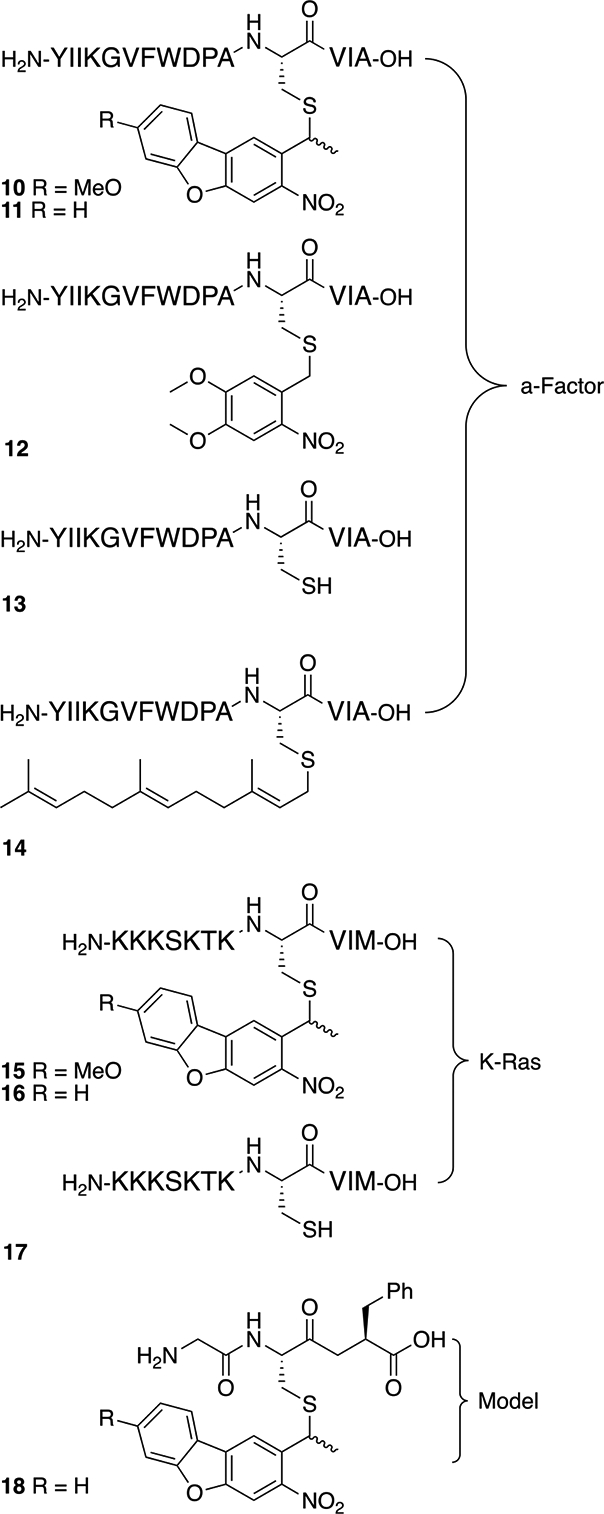

With the desired building block in hand, a series of peptides (10-18, Figure 2) based on two different sequences incorporating the caged cysteine residue were prepared. First, a 15-residue peptide based on the sequence of a-factor, a yeast pheromone, was prepared starting with Fmoc-Ala on Wang resin. Fmoc-deprotection and two cycles of standard SPPS using an automated synthesizer yielded a VIA tripeptide on resin. Next, N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1) was coupled offline with ninhydrin monitoring to insure complete reaction; to increase the coupling efficiency, the coupling time was extended to 4 hours for this modified cysteine residue. At that point, automated peptide synthesis was resumed to complete the synthesis. After final Fmoc-deprotection, the peptide was cleaved from the resin under acidic conditions, precipitated with ether, and the resulting crude material purified via reversed-phase HPLC to yield the desired peptide. The final peptide, 10, was analyzed via LC-MS/MS to confirm the sequence (Table S1). a-Factor-based peptides 11 and 12 containing NDBF- and NV-protected cysteine were also prepared and characterized in a similar manner (see Tables S2 and S3). A second peptide sequence based on the C-terminus of the human K-Ras protein was also synthesized. Forms of that peptide containing either Cys(MeO-NDBF) (15) or Cys(NDBF) (16) were prepared. Following purification of the complete peptides, their sequences were again confirmed via LC-MS/MS analysis (Tables S4 and S5).

Figure 2.

Synthetic peptides containing MeO-NDBF-, NBDF- and NV-protected cysteine residues prepared in this study.

In the initial preparation and purification of 10, the HPLC chromatogram of the crude peptide revealed the presence of two double peaks: a main double peak corresponding to ~70–80% of the total integrated area, and a minor double peak corresponding to ~20–30% of the total integrated area. The double peak pattern was clearer for the NDBF-protected peptides 11 and 16 (Figures S1 and S2). For each peptide, all four peaks exhibited identical m/z values and MS/MS fragmentation patterns. We attribute the two species present in each of the double peaks as resulting from a mixture of two epimers due to the stereogenic center adjacent to the dibenzofuran since bromide 8 was used as a racemic mixture. We attribute the major double peak to be from the desired L-cysteine-containing peptides and the minor double peak to be from D-cysteine-containing peptides that arise due to racemization of the protected cysteine either during the hydrolysis of ester 9 or in the subsequent activation of 1 during SPPS. This structural assignment is supported by the fact that peak doubling was not observed with peptide 12 (Figure S3) which does not have the additional stereogenic center present in 10 and 11 (since the NV group lacks the methyl group present in the NDBF and MeO-NDBF protecting groups); however, 12 did have one major and one minor peak of identical mass, presumably due to racemization of the cysteine as noted above. This hypothesis was further corroborated when photolysis of the combined double peaks (from 11) led to the generation of two product peaks (13) exhibiting the same m/z ratio, whereas photolysis of the purified major double peak lead to the generation of a single product peak (Figure S4). While it was possible to remove the minor components via HPLC separation and use the resulting material for subsequent experiments, this may not always be possible depending on the specific peptide sequence under study. Hence, the epimerization process was studied in more detail to obtain a more optimized synthetic procedure.

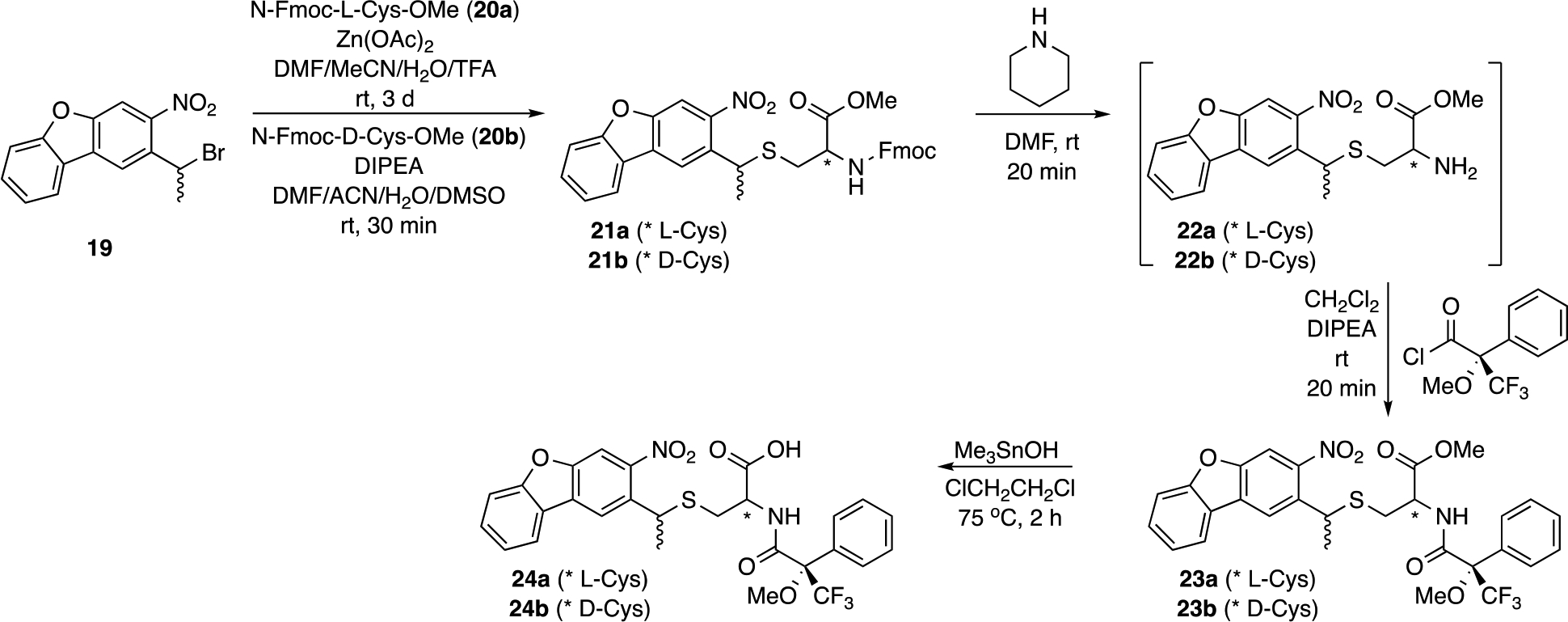

To better understand the origin of the epimerization observed here, we first elected to study the hydrolysis of a Mosher’s amide of NDBF-protected cysteine methyl ester (23a) to the corresponding acid (24a). Accordingly, that compound was prepared from 21a by removal of the Fmoc group followed by acylation with (S)-Mosher’s acid chloride [(S)-(+)-α-methoxy- α- (trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride] to yield the desired cysteine methyl ester derivative (23a). Inspection of the 19F NMR revealed the presence of two signals at −69.03 and −68.92 ppm, consistent with the presence of two diastereomers (with equal integration) due to the epimeric mixture, resulting from the stereogenic center present in the NDBF group. Hydrolysis of the ester to the corresponding acid (24a) under conditions necessary to obtain complete conversion (Me3SnOH, DCE, 75°, 12 h) and subsequent 19F NMR analysis showed only two signals (at −69.02 and −68.92 ppm, Figure 3A) suggesting that no epimerization had occurred in the hydrolysis reaction; even when ester 23a was subjected to more forcing conditions (Me3SnOH, DCE, 85°, overnight), no additional peaks in the 19F NMR were observed. To confirm the absence of epimerization, the authentic product (the diastereomeric ester containing D-cysteine) was independently prepared by reacting bromide 19 with N-Fmoc-D-cysteine methyl ester followed by Fmoc removal and acylation with (S)-Mosher’s acid chloride to yield 23b. Analysis of that material via 19F NMR showed two signals at −68.86 and −68.82 ppm that are different than those present in the material produced from L-cysteine demonstrating that the two cysteine derivatives (prepared from the enantiomers of cysteine) can be clearly distinguished via 19F NMR. Hydrolysis of the D-cysteine analogue (23b) yielded the corresponding acid (24b) whose 19F NMR manifested two signals at −68.80 and 68.78 ppm (Figure 3B); an 19F NMR of a mixture of 24a and 24b confirms these chemical shift differences are real (Figure 3C). This result validates the use of 19F NMR to monitor this epimerization process and suggests that no significant level of epimerization occurs in the hydrolysis of 9 to 1.

Figure 3.

Study of the hydrolysis of a Mosher amide of NDBF-protected L-cysteine via 19F NMR. A: 19F NMR of compound 24a, obtained after hydrolysis of 23a. B: 19F NMR of compound 24b, prepared from D-cysteine. This corresponds to the product that would form from cysteine racemization during coupling leading to an epimeric peptide product. 19F NMR of a mixture of compounds 24a and 24b, showing the difference in chemical shifts between the two epimers.

Next, we examined the potential for epimerization during SPPS. Karas et al. previously reported that variable amounts of racemization occur in the activation of N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NV)-OH depending on the precise coupling conditions used.14 We initially adjusted our synthetic conditions and employed the optimal conditions described by them, consisting of activation and coupling of 1 with 4 equivalents of N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) and 6-chloro-1-hydroxybenzotriazole (Cl-HOBt) for 1 hour, for the synthesis of 10. However, LC-MS/MS analysis of the resulting material after synthesis still showed significant epimerization (Figure S5). To confirm that the epimerization was occurring in the activation/coupling step of the protected cysteine residue, a model tripeptide GC(NDBF)F (18) was prepared and subjected to prolonged treatment (2 h) with 20% piperidine/DMF to duplicate the exposure to base that the embedded cysteine residue would experience (12 deprotection steps) necessary to complete the synthesis of a-Factor. Comparison of chromatograms obtained of the tripeptide before and after extensive piperidine treatment showed that no additional epimerization had occurred (Figure S6), suggesting that cysteine racemization must be occurring in the activation step. To minimize potential racemization, several different coupling conditions for the caged cysteine residue were investigated by synthesizing peptide 18 and subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis. Of the conditions surveyed, the use of benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP), 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt) and DIEA gave the best results with less than 2% racemization being observed. To confirm the utility of these revised conditions, peptide 15 was resynthesized using 4 equivalents PyBOP/HOAT/DIEA for 30 min at a concentration of 150 mM. After global deprotection and resin cleavage with Reagent K, LC-MS analysis (Figure 4) showed less than 2% of the epimerized product was present. Overall, these results indicate that NDBF-based protection of cysteine can be used to efficiently prepare caged peptides. However, careful reaction monitoring is important to minimize potential racemization during SPPS.

Figure 4.

LC-MS of crude peptide 15 synthesized using PyBOP, HOAT and DIEA shows minimal epimerized product. The desired peptide elutes as a double peak centered at 33.3 min. Note the near complete absence of epimerized product at 36.4 min. The coupling conditions for 1 to resin-bound VIM consisted of 4 equivalents of PyBOP, HOAT and DIEA at 150 mM in DMF for 30 min.

Photochemistry.

Previous work with o-nitrobenzyl-based protecting groups showed that the addition of methoxy substituents to the nitrobenzyl chromophore shifted the absorbance maximum to lower energy; that was accompanied by a decrease in the quantum yield for photolysis. Comparison of the UV spectra of the parent compound, N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NDBF)-OH (2), and N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1), shown in Figure 5, indicates an increase in the absorbance maximum from 320 to 355 nm, consistent with the aforementioned simple o-nitrobenzyl-based system; in fact the absorbance maximum for 1 is quite similar to that of the simpler nitroveratryl group present in N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NV)-OH. Inspection of the UV spectra also shows that the extinction coefficients of the compounds at their λmax vary less than 2-fold with the MeO-NDBF-protected residue exhibiting the highest value. At 350 nm, the wavelength used for the UV irradiation experiments described below, the extinction coefficient for the MeO-NDBF-protected residue is 1.9-fold higher than that for the NDBF-protected parent compound (Table 1).

Figure 5.

UV spectra of protected forms of cysteine suitable for SPPS used in this study.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of caged molecules employed in this study.

| Protected Cysteine | (λmax)a (nm) | ε (λmax)a (M−1cm−1) | ε (350 nm)a (M−1cm−1) | Φ (350)c (mol/ein) | δu (800 nm)d (GM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Fmoc-L-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1) | 355 | 8,780 | 8,750 | 0.53e | 0.71e 1.4f |

| N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NDBF)-OH (2) | 320b | 5,990 | 4,600 | 0.70g | 0.20g |

| N-Fmoc-L-Cys(NV)-OH | 350 | 6,290 | 6,290 | 0.023h | - |

Measured in H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v).

Fmoc-Cys(NDBF)-OH (2) exhibits a broad maximum.

Measured in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 containing 15 mM DTT.

Measured in H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA.

Measured using peptide 10.

Measured using peptide 15.

Measured using peptide 11.

Measured using peptide 12.

Photolysis of peptides 10 and 11 using a Rayonet reactor centered at 350 nm and subsequent LC-MS analysis showed that the two protecting groups uncage at comparable rates (Figure S7). Since the bulbs used in these experiments manifest a fairly broad spectral bandwidth (~ 50 nm at half height), it is not possible to determine the quantum yields of these two protecting groups from these experiments. However, it is clear from an operational perspective (using a Rayonet reactor common to many laboratories performing photolysis experiments) that these two protecting groups have similar UV photolysis properties. Those results are in stark contrast to those obtained with peptide 12 that incorporates an NV-protected cysteine where the rate of photolysis is 25-fold slower compared with peptide 10 (containing a MeO-NDBF-protected cysteine residue); using 14 bulbs in a Rayonet reactor, peptides 10 and 11 are essentially completed deprotected in less than 30 seconds; for comparison, at that point, ~90% of the NV-protected peptide remains unreacted (Figure S7). Those results are similar to what we previously reported18 in comparing the monomeric precursors Fmoc-Cys(NDBF)-OMe and Fmoc-Cys(NV)-OMe and highlight a key feature of NDBF-based thiol protection, namely that it is much more sensitive to UV photolysis compared with the simpler NV group.

To quantify the photophysical properties of peptides 10 and 11 in more detail, photolysis reactions were performed at low concentration to minimize any inner filter effect using an apparatus (Figure S8) equipped with 350 nm LEDs with a narrower spectral bandwidth (~ 10 nm at half height, Figure S9). After determining the intensity of the light source via ferrioxylate actinometry, the apparatus was used to determine the rate of photolysis for peptides 10, 11 and 12 (Figure 6A, Figure S10 and Table S6) and calculate their respective quantum yields. Values of 0.53, 0.70 and 0.023 were obtained for 10, 11 and 12, respectively (Table 1). It should be noted that the value obtained for peptide 11 that incorporates an NDBF-protected thiol is comparable to the value reported for NDBF-EGTA (0.7), a caged alcohol. These results quantitatively illustrate the greater efficiency of NDBF-based protecting groups as photoremovable moieties compared with NV-based compounds and serve to highlight their utility for uncaging applications.

Figure 6.

Photolysis of caged peptides via one and TP excitations. Above: Kinetic analysis of photolysis of MeO-NDBF-, NBDF- and NV-containing a-Factor-based peptides (10, 11 and 12, respectively) using a 350 nm LED reactor. Below: Kinetic analysis of photolysis of NBDF- and MeO-NDBF-containing a-Factor-based peptides (10 and 11, respectively) and MeO-NDBF-containing K-Ras-based peptide (15) using a 800 nm Ti:Saphire laser employing BhcOAc as a reference standard. For both the UV and TP photolysis reactions, each reaction was performed in triplicate and the resulting data averaged and used to create the above plots.

One of the most important features of the NDBF protecting group is that it manifests a significant TP action cross-section for uncaging, making it useful for biological experiments. Accordingly, we wanted to study the rates of photolysis of peptides 10 and 11 upon TP activation. Thus, solutions of the peptides were irradiated at 800 nm using a Ti:Saphire laser followed by LC-MS analysis. Interestingly, peptide 10 containing the MeO-NDBF-protected cysteine residue uncaged at a rate 3.6-fold greater than peptide 11 containing the parent NDBF-protected cysteine (Figure 6B). Furthermore, irradiation of the K-Ras-derived, MeO-NDBF-containing peptide 15 manifested an additional 2-fold rate increase compared to the MeO-NDBF-containing a-Factor-derived peptide 10. Using BhcOAc as a standard, we estimate the TP action cross-section for MeO-NDBF deprotection to be 0.7 GM for 10 and 1.4 GM for 15. Presumably, the observed variation in the TP action cross-section of different peptides incorporating the same chromophore reflects differences in the local structure/environment around the chromophore; such results have been observed in homologues of GFP where the fluorophore is constant throughout.26 Overall, these results constitute a significant improvement in TP photolysis efficiency and suggests that the MeO-NDBF protecting group could be particularly useful for TP activation of peptides containing caged cysteines in cells or even tissue.

Enzymatic reactions initiated by thiol uncaging.

Caged peptide substrates have potentially significant utility in cell-based biological experiments since they are unreactive prior to photolysis. Peptides can be incubated with cells and allowed to accumulate before activation with light. As a prelude to such cell-based experiments, we sought to investigate whether photolysis of peptides containing MeO-NDBF protected cysteine residues could be used to liberate peptides that could serve as substrates for enzymatic reactions. Protein farnesylation involves the transfer of the isoprenyl group from farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) to proteins bearing C-terminal CaaX-box sequences.27 Protein farnesyltransferase (PFTase) which catalyzes this reaction has been intensely studied as a possible therapeutic target for a number of diseases including cancer.28,29 Initially, peptide 10 was incubated in the presence of PFTase and the substrate FPP and irradiated for 30 sec in a Rayonet photoreactor using three 350 nm bulbs. Analysis of the resulting photolysis reaction via LC-MS before and after photolysis indicated that essentially all of the starting peptide 10 (Figure S11A, before photolysis) had been converted to the corresponding farnesylated product 14 (Figure S11C, after photolysis); in the absence of PFTase, the deprotected thiol, 13, was the major species (Figure S11B, no PFTase).

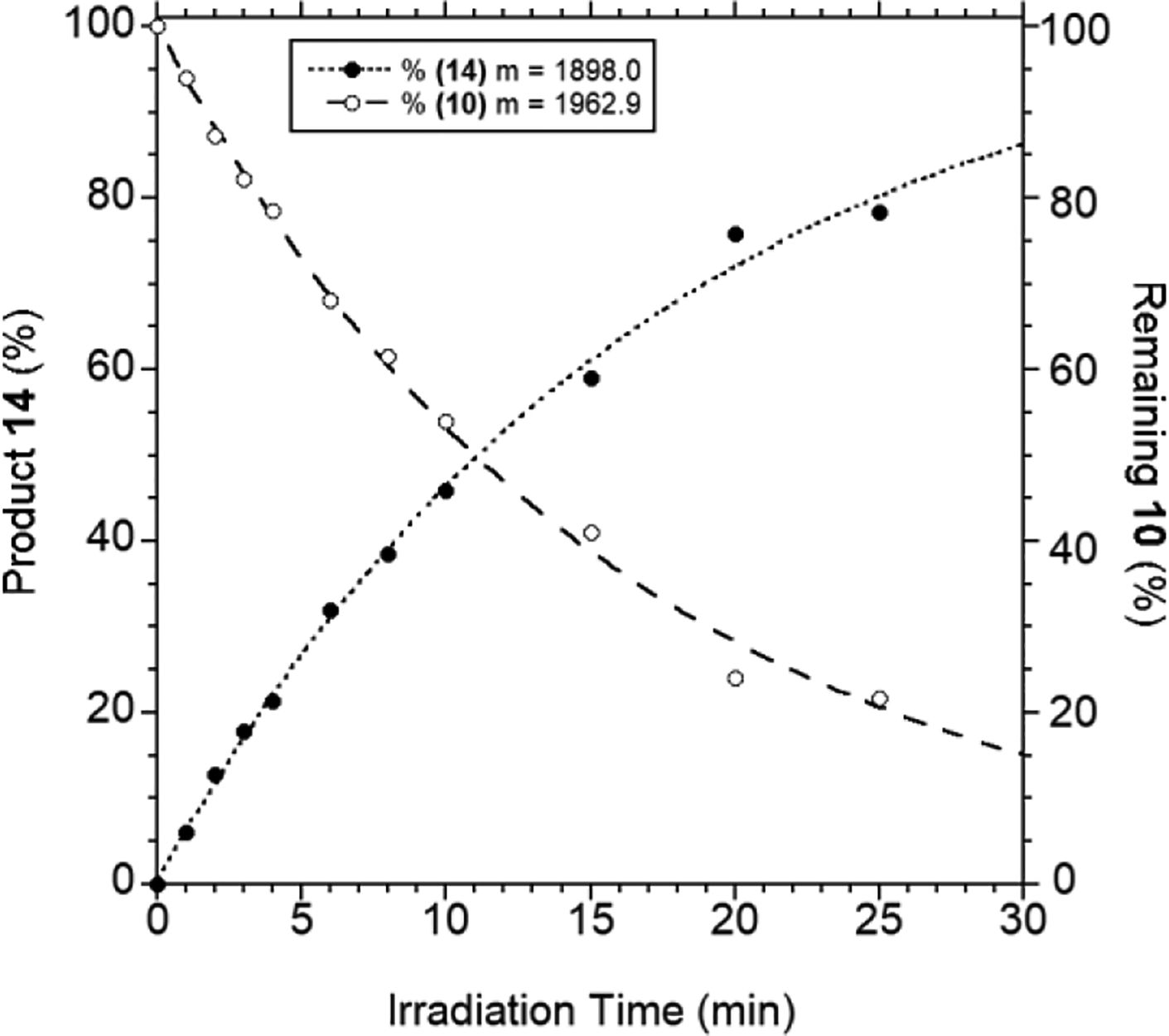

Next, we explored the TP-mediated process. Accordingly, peptide 10 was incubated in the presence of PFTase and FPP and irradiated at 800 nm for 10 minutes using the laser system described above. Analysis of the resulting photolysis reaction via LC-MS before and after photolysis indicated substantial conversion of the starting peptide 10 (Figure 7A, before photolysis) to the corresponding farnesylated product 14 (Figure 7C, after photolysis) with a small amount of the free thiol (13) remaining. In contrast, in the absence of PFTase, the major species present after irradiation was the free thiol (13) (Figure 7B, after photolysis without PFTase). To explore the dose dependence of this photochemical reaction, samples containing 10, PFTase and FPP were irradiated at 800 nm for different times and the amounts of starting peptide (10) and farnesylated product (14) were quantified from LC-MS analysis. A plot of that data (Figure 8) showed a clear relationship between light exposure and product formation. Importantly, under these conditions, significant quantities of the farnesylated product (~20%) were easily detected within the first five minutes of irradiation, highlighting the efficiency of this process.

Figure 7.

Analysis of PFTase-catalyzed farnesylation after TP-activated photolysis of 10. In each case, reactions were monitored by LC-MS with single ion monitoring (SIM) of the protected peptide (10), the uncaged free thiol (13) and the farnesylated product (14). Panel A: LC-MS analysis of a reaction containing 10 and PFTase before irradiation at 800 nm. Panel B: LC-MS analysis of a reaction containing 10 without PFTase after irradiation at 800 nm. Panel C: LC-MS analysis of a reaction containing 10 with PFTase after irradiation at 800 nm.

Figure 8.

Quantification of starting peptide 10 and enzymatically farnesylated product 14 from TP-activated photolysis of 10 at 800 nm conducted for different durations in the presence of PFTase and FPP.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, the efficiency of TP-mediated thiol deprotection in cysteine-containing peptides was improved using a new methoxy-substituted analogue of NDBF. An efficient synthesis was developed to prepare Fmoc-Cys(MeO-NDBF)-OH (1), a protected form of cysteine suitable for SPPS; installation of the methoxy substituent increased the absorption maximum from 320 nm (NDBF) to 355 nm (MeO-NDBF). The cysteine analogue was incorporated into two known bioactive peptides including a-Factor precursor (10, a pentadecapeptide) and a fragment from the C-terminus of K-Ras (15, an undecapeptide). UV irradiation of these MeO-NDBF-protected peptides resulted in deprotection at rates comparable to those of peptides masked with the parent NDBF group but 25-fold faster compared to an NV-protected peptide due to the larger quantum yield measured for the NDBF-based caging groups. However, TP activation at 800 nm showed significant differences between the two caging groups with the TP action cross-sections for 10 and 15 determined to be 0.71 and 1.4 GM, respectively using BhcOAc as a standard. These are 3.5- and 7-fold higher for 10 and 15, respectively, compared to the previously reported value for the parent NDBF group of 0.2 GM, also reproduced here using peptide 11. Finally, deprotection of peptide 10 using either UV or 800 nm light rapidly liberated the free thiol form (13) which was efficiently enzymatically transformed to its farnesylated congener (14) via the action of PFTase. These experiments set the stage for future cell-based experiments using this more efficiently removable protecting group. Finally, the results described here, demonstrating an increase in TP action cross-section upon introduction of a methoxy substituent, suggest additional exploration of the NDBF scaffold is warranted.

EXPERIMENTAL

General Details.

HPLC and LC-MS Grade H2O and CH3CN as well as HOATwere purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh PA). Fmoc-Cys-OH was purchased from Chem-Impex International (Wood Dale, IL). All other protected amino acids and resins were purchased from P3 BioSystems (Louisville, KY). HCTU was purchased from Oakwood Chemical (Estill, SC). PyAOP was purchased from EMD Millipore (Burlington, MA). Other solvents and reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were used without further purification. 1H NMR data of synthetic compounds were recorded at 500 MHz on a Bruker Avance III HD Instrument at 25 °C. Liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent 1200 series LCMSD SL single quadrupole system equipped with a C3 column (Agilent ZORBAX 300SB-C3, 5 μM, 4.6 × 250 mm) and a variable wavelength detector. An H2O/CH3CN solvent system containing 0.1% HCO2H was used, consisting of solvent A (H2O with 0.1% HCO2H) and solvent B (CH3CN with 0.1% HCO2H). High resolution mass spectrometry and MS/MS fragmentation of peptides was performed using a Thermo Scientific Elite Orbitrap instrument. High resolution mass spectra of organic compounds were acquired using either a Bruker BioTOF II ESI/TOF-MS, or an Applied Biosystems-Sciex 5800 MALDI-TOF instrument. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification was performed using an Agilent 1100 series instrument equipped with a diode-array detector and C18 columns (Agilent ZORBAX 300SB-C18 5 μM 9.4 × 250 mm, or Agilent Pursuit C18 5 μM 250 × 21.2mm, respectively), and using an H2O/CH3CN system containing trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) consisting of solvent A (H2O with 0.1% TFA) and solvent B (CH3CN with 0.1% TFA).

4-(2-bromo-5-methoxyphenoxy)-2-nitrobenzaldehyde (3).

4-fluoro-2-nitrobenzaldehyde (2.29 g, 13.6 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (100 mL). 2-bromo-5-methoxyphenol (2.62 g, 12.9 mmol) and K2CO3 (5.4 g, 39 mmol) were then sequentially added and the reaction was purged with Ar (g) and stirred at rt for 6 h and then 50 °C for 12 h in an oil bath. The reaction progress was followed by TLC. After the reaction was deemed complete, the mixture was cooled to rt and poured into aqueous NH4Cl (200 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The organic phase was washed with H2O (500 mL), brine (500 mL), dried with anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated to dryness. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Hexanes/EtOAc, 4:1, v/v) to yield 4.4 g (98%) of product 3 as a pale yellow solid. mp 62–64 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 2.1, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (dd, J = 2.8, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 2.8, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 186.8, 161.4, 160.6, 151.4, 151.1, 134.5, 131.7, 125.0, 120.8, 113.7, 111.9, 108.9, 106.1, 55.8. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C14H10BrNNaO5 [M+Na]+: 373.9635; found: 373.9610.

2-(4-(2-bromo-5-methoxyphenoxy)-2-nitrophenyl)-1,3-dioxolane (4).

Compound 3 (5 g, 14.2 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (300 mL). Ethylene glycol (5 mL) and p-toluene sulfonic acid monohydrate (500 mg, 2.91 mmol) were added. The reaction was purged with Ar (g) and stirred at 110 °C in an oil bath using a Dean-Stark trap. Reaction progress was monitored by TLC. After completion of this reaction, the mixture was cooled to rt and poured into aqueous NaHCO3 (200 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 150 mL). The organic phase was washed with H2O (100 mL), brine (100 mL), dried with anhydrous MgSO4, evaporated to dryness, and purified by column chromatography (Hexanes/EtOAc, 3:1, v/v) to yield 5.1 g (95%) of product 4 as a sticky oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.74 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (dd, J = 2.5, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (dd, J = 2.9, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (dd, J = 2.9, 1H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 4.04 (s, 4H), 3.78 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 160.5, 158.0, 152.3, 149.7, 134.4, 129.5, 127.4, 121.0, 113.0, 112.9, 108.4, 106.2, 99.5, 65.5, 55.9. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C16H14BrNNaO6 [M+Na]+, 417.9897; found: 417.9886.

2-(1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)-7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan (5).

Compound 4 (3 g, 8.1 mmol) was dissolved in dimethylacetamide (60 mL). NaOAc (1.0 g, 12.2 mmol) and Pd/C (0.228 mmol, 239 mg) were added into this mixture. The reaction was stirred at 115 °C in an oil bath and the progress followed by NMR at selected intervals. The reaction was deemed complete after 2 days. After filtration through a pad of Celite®, the filtrate was diluted with EtOAc (80 mL), and poured into NH4Cl aqueous solution (200 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 150 mL). The organic phase was washed with H2O (100 mL), brine (100 mL), and was then dried over anhydrous MgSO4, evaporated to dryness, and purified by column chromatography (Hexanes/EtOAc, 3:1, v/v) to yield 2.2 g (85%) of product 5, isolated as a yellow solid. mp 220–222 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 4.12 (s, 4H), 3.93 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 161.8, 160.2, 155.0, 146.2, 128.91, 128.89, 122.3, 118.6, 115.8, 112.9, 108.9, 100.09, 96.7, 65.5, 56.0. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C16H13NNaO6 [M+Na]+, 338.0635; found: 338.0619.

7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-carbaldehyde (6).

Compound 5 (3 g, 9.5 mmol) was dissolved in a THF/H2O solvent mixture (100 mL, 3:1, v/v), and then p-toluene sulfonic acid monohydrate (300 mg, 1.74 mmol) as added. The reaction was stirred at 60 °C in an oil bath and reaction progress was monitored by TLC. After 24 h THF in the resulting solutions was removed by vacumn and the desired product was precipitated, product 6 was isolated through filtration to yield 2.1 g (83%), as a red solid. mp 205–208 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 10.51 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 188.2, 162.5, 160.6, 157.2, 147.5, 129.9, 127.8, 122.7, 120.9, 115.3, 113.7, 108.7, 96.8, 56.1. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C14H9NNaO5 [M+Na]+, 294.0373; found: 294.0401.

1-(7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethan-1-ol (7).

Trimethylaluminum (0.55 mL, 1.1 mmol; 2 M solution in hexanes) was added dropwise over 10 min to a solution of 6 (150 mg, 0.55 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (3 mL) under Ar at 0 °C. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 1 h, after which it was quenched with ice-cold water (50 mL), followed by addition of 1 M NaOH (5 mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 min, after which time additional CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added and the resulting organic layer was washed with 1 M NaOH (50 mL), brine (50 mL), dried over MgSO4 and the volatiles were evaporated, affording crude 7. The crude product was passed through a thin pad of SiO2 eluted with EtOAc/Hexanes (150 mL, 1:3, v/v) to yield 123 mg (85%) of pure product 7, as a yellow solid. mp 140–142 °C. 1H NMR (THF-D8, 500 MHz) δ 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dd, J = 1.5, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 5.50–5.45 (m, 1H), 4.71 (d, J = 3.74 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 1.54 (d, J = 6.25 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (THF-D8, 125 MHz) δ 161.9, 160.0, 153.7, 145.1, 138.8, 129.0, 122.1, 118.2, 115.6, 112.4, 107.1, 96.5, 64.8, 55.2, 25.2. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C15H13NNaO5 [M+Na]+, 310.0686; found: 310.0671.

2-(1-bromoethyl)-7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan (8).

To compound 7 (126 mg, 0.44 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) in an ice bath, PPh3-polymer supported (1.1 mmol, ~ 3 mmol/g, 367 mg), and CBr4 (273 mg, 0.825 mmol) were introduced. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. After filtration through a pad of Celite®, the filtrate was collected, and the solvent evaporated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hex/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) to give 120 mg (78%) of the desired product, 8, as a yellow solid. mp 168 °C (decomposed). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.29 (s, 1H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 2.2, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.04 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 2.20 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ162.0, 160.3, 154.3, 144.9, 133.6, 129.6, 122.4, 120.5, 115.4, 112.9, 108.3, 96.7, 56.0, 43.1, 28.0. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C15H12BrNO4Na [M+Na]+, 371.9842; found: 371.9872.

Methyl N-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)-S-(1-(7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-L-cysteinate (9).

Product 8, Fmoc-L-Cysteine methyl ester (327 mg, 0.93 mmol) and Zn(OAc)2 (438 mg, 2.0 mmol) were dissolved in 30 mL of a mixture of DMF/ACN/0.1% TFA in H2O (4:1:1, v/v/v). The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/Et2O, 1:1, v/v) and stopped after 24 h of stirring at rt by pouring the reaction mixture into H2O (100 mL), and extraction with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) three times. The organic phase was washed with 100 mL of brine, and was then dried over anhydrous MgSO4, evaporated to dryness, and purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 3:1, v/v) to give 221 mg (38%) of the desired product 9, isolated as a yellow sticky oil, as a diastereomeric mixture. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 4H), 7.62–7.56 (m, 4H), 7.41–7.38 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 4H), 7.09–6.91 (m, 4H), 5.59–5.55 (m, 2H), 4.92–4.85 (m, 2H), 4.59–4.56 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.49 (m, 1H), 4.39–4.32 (m, 2H), 4.28–4.20 (m, 3H), 4.15–4.11 (m, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 2.98–2.85 (m, 4H), 1.71–1.69 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ171.1, 161.9, 161.8, 160.1, 155.8, 153.9, 146.6, 146.5, 144.0, 143.9, 141.41, 141.38, 141.37, 134.1, 134.0, 129.6, 129.5, 127.9, 127.3, 125.3, 122.4, 122.3, 120.09, 120.07, 119.98, 119.90, 115.5, 112.79, 112.71, 108.14, 108.09, 100.11, 96.66, 96.63, 67.49, 67.45, 55.99, 55.96, 53.77, 53.71, 52.96, 52.93, 47.19, 47.11, 40.0, 39.7, 34.22, 34.10, 23.86, 23.74. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C34H30N2O8SNa [M+Na]+, 649.1615; found: 649.1629.

N-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)-S-(1-(7-methoxy-3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-L-cysteine (1).

Ester 9 (300 mg, 0.48 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) and Me3SnOH (226 mg, 1.25 mmol) was added. The reaction was refluxed for 12 h in an oil bath and monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1, v/v), at which point the solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting oil dissolved in EtOAc (30 mL). The organic layer was washed with 5% HCl (3 × 10 mL) and brine (3 × 10 mL), dried over MgSO4, and evaporated to give 267 mg of the desired product (89%) as a yellow foam, present as a diastereomeric mixture. mp 64–66 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (m, 4H), 7.60–7.55 (m, 4H), 7.45–7.38 (m, 4H), 7.32–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.06–6.91 (m, 4H), 5.63–5.60 (m, 2H), 4.93–4.89 (m, 2H), 4.60–4.59 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.50 (m, 1H), 4.36–4.34 (m, 2H), 4.30–4.21 (m, 3H), 4.15–4.11 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.01–2.89 (m, 4H), 1.71–1.68 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 161.8, 160.1, 156.0, 153.9, 146.5, 146.4, 143.0, 141.41, 141.38, 141.36, 133.98, 134.0, 129.6, 129.5, 127.8, 127.2, 125.3, 122.4, 122.3, 120.09, 120.07, 119.93, 119.90, 115.47, 115.44, 112.75, 112.71, 108.19, 96.6, 67.59, 67.57, 55.98, 55.96, 53.42, 53.41, 47.16, 47.05, 39.77, 39.70,33.76, 33.73, 31.09, 23.77, 23.73. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C33H28N2O8NaS [M+Na]+, 635.1459; found: 635.1479.

Methyl N-(((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)-S-(1-(3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-D-cysteinate (21b).

N-Fmoc-D-Cysteine methyl ester 20b (179 mg, 0.5 mmol) and 19 (160 mg, 0.5 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL of a mixture of DMSO/DMF/ACN/H2O (3:3:1:1, v/v/v/v), and then, DIPEA (0.1 mL) was added into this solution. The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) and stopped after 30 min of stirring at rt by pouring the reaction mixture into H2O (100 mL), and extraction with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The organic phase was washed with 100 mL of brine, and was then dried over anhydrous MgSO4, evaporated to dryness, and purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1 to 3:1, v/v) to give 160 mg (53%) of the desired product 21b, isolated as a yellow sticky oil, as a diastereomeric mixture. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.07–8.00 (m, 4H), 7.65–7.55 (m, 10H), 7.79–7.77 (m, 4H), 7.65–7.56 (m, 8H), 7.47–7.33 (m, 10H), 5.59 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 4.90–4.84 (m, 2H), 4.62–4.58 (m, 1H), 4.56–4.52 (m, 1H), 4.43–4.36 (m, 2H), 4.32–4.24 (m, 3H), 4.19–4.12 (m, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.01–2.87 (m, 4H), 1.76–1.73 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 170.9, 158.3, 155.65, 155.56, 153.7, 147.74, 147.69, 143.9, 143.8, 141.29, 141.27, 141.23, 136.6, 133.6, 133.5, 129.47, 129.45, 129.42, 129.25, 129.01, 128.90, 127.78, 127.70, 127.1, 125.2, 123.80, 123.78, 123.76, 122.6, 122.4, 121.83, 121.81, 121.76, 121.0, 120.9, 120.04, 120.02, 119.95, 119.21, 112.25, 112.22, 112.19, 108.4, 108.2, 67.34, 67.29, 65.9, 53.6, 53.5, 52.82, 52.80, 47.1, 47.0, 29.8, 29.5, 34.1, 34.0, 27.1, 24.8, 23.7, 23.6. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C33H28N2NaO7S [M+Na]+, 619.1515; found: 619.1507.

Methyl S-(1-(3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-N-((S)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoyl)-L-cysteinate (23a).

Methyl ester 21a (100 mg, 0.168 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of a mixture of DMF/piperidine (4:1, v/v). The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) and stopped after 30 min of stirring at rt, the solvents were removed using a stream of air, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v, to EtOAc) to remove the byproduct and remaining starting materials. The purified product 22a and Mosher’s acid chloride [(S)-(+)-α-methoxy- α- (trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chloride] (51 mg, 0.2 mmol) were dissolved in 1 mL dry CH2Cl2, then DIEPA (0.1 mL) was added into this mixture. The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) and stopped after 20 min of stirring at rt, the solvents were removed under vacuum, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) to give 85 mg (86%) of the desired product 23a, isolated as a yellow sticky oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.43 (s, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.09–8.06 (m, 4H), 7.66–7.52 (m, 11H), 7.48–7.41 (m, 9H), 4.88–4.76 (m, 4H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.69 (s, 3H), 3.44 (s, 3H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 3.09–2.99 (m, 2H), 2.94–2.88 (m, 2H), 1.77 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.73 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 170.4, 170.3, 166.3, 166.2, 158.32, 158.28, 153.7, 147.8, 147.7, 133.4, 133.2, 129.6, 129.5, 129.1, 128.9, 128.6, 127.9, 123.7 (q, J = 289.9 Hz, CF3), 123.81, 123.79, 122.39, 122.37, 121.9, 121.8, 121.0, 120.8, 112.25, 112.19, 108.24, 108.19, 84.13 (q, J = 28.0 Hz, C-CF3), 83.92 (q, J = 28.0 Hz, C-CF3), 55.1, 52.84, 52.80, 51.89, 51.83, 43.5, 39.7, 39.3, 33.7, 33.3, 23.6, 23.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 470 MHz) δ −68.9, −69.0. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C28H25F3N2NaO7S [M+Na]+, 613.1227; found: 613.1234.

S-(1-(3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-N-((S)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoyl)-L-cysteine (24a).

Ester 23a (80 mg, 0.136 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of ClCH2CH2Cl, and Me3SnOH (49 mg, 0.271 mmol) was added. The reaction was heated at 75 °C in an oil bath for 2 h and then cooled down to rt. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting oil was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 100:5, v/v) to give 71 mg (91%) of the desired product 24a, isolated as a yellow sticky oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.08–8.03 (m, 4H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.55 (m, 10H), 7.47–7.36 (m, 9H), 4.89–4.74 (m, 4H), 3.42 (s, 3H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 3.12–2.88 (m, 4H), 1.75 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.71 (d, J = 6.4Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ166.6, 166.5, 158.29, 158.25, 153.6, 147.7, 147.5, 133.4, 133.2, 131.9, 131.8, 129.60, 129.53, 129.1,129.45, 129.43, 129.1, 128.9, 128.6, 127.9, 123.7 (q, J = 289.9 Hz, CF3), 123.8, 122.4, 121.9, 121.8, 121.0, 120.9, 112.16, 108.25, 108.18, 84.02 (q, J = 26.9 Hz, C-CF3), 83.92 (q, J = 27.0 Hz, C-CF3), 55.1, 52.0, 51.8, 39.5, 39.2, 33.4, 33.0, 29.7, 29.2, 23.5, 23.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 470 MHz) δ −68.9, −69.0. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C27H22F3N2O7S [M-H]+, 575.1105; found: 613.1085.

Methyl S-(1-(3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-N-((S)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoyl)-D-cysteinate (23b).

Methyl ester 21b (100 mg, 0.168 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of a mixture of DMF/piperidine (4:1, v/v). The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) and stopped after 30 min of stirring at rt, the solvents were removed using a stream of air, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v, to EtOAc) to remove the byproduct and remaining starting materials. The purified product 22b and Mosher’s acid chloride (51 mg, 0.2 mmol) were dissolved in 1 mL dry CH2Cl2, then DIEPA (0.1 mL) was added into this mixture. The reaction was monitored by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) and stopped after 30 min of stirring at rt, the solvents were under vacuum, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (Hexanes/EtOAc, 5:1, v/v) to give 80 mg (81%) of the desired product 23b, isolated as a yellow sticky oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.35 (s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.04–8.00 (m, 4H), 7.65–7.57 (m, 9H), 7.51 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.38 (m, 10H), 4.88–4.70 (m, 4H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.51 (s, 6H), 3.01–2.96 (m, 2H), 2.88–2.82 (m, 2H), 1.68 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.65 (d, J = 6.9Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 170.4, 170.3, 166.4, 166.3, 158.29, 158.26, 153.6, 147.67, 147.65, 133.24, 133.15, 132.42, 132.39, 129.6, 129.5, 129.0, 128.8, 128.49, 128.47, 127.8, 127.6, 123.62 (q, J = 290.0 Hz, CF3), 123.60 (q, J = 290.2 Hz, CF3),123.81, 123.79, 122.35, 122.34, 121.9, 121.7, 120.9, 120.8, 112.26, 112.20, 108.24, 108.19, 84.0 (q, J = 26.4 Hz, C-CF3), 83.9 (q, J = 26.4 Hz, C-CF3), 55.19, 55.18, 52.88, 52.86, 51.92, 51.39, 39.6, 39.2, 33.7, 33.3, 23.5, 23.4. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 470 MHz) δ −68.8, −68.9. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C28H25F3N2NaO7S [M+Na]+, 613.1227; found: 613.1250.

S-(1-(3-nitrodibenzo[b,d]furan-2-yl)ethyl)-N-((S)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoyl)-D-cysteine (24b).

Ester 23b (80 mg, 0.136 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of ClCH2CH2Cl, and Me3SnOH (49 mg, 0.271 mmol) was added. The reaction was heated at 75 °C in an oil bath for 2 h and then cooled down to rt. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting oil was purified by column chromatography on SiO2 (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 100:5, v/v) to give 69 mg (90%) of the desired product 24b, isolated as a yellow sticky oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.28 (s, 1H), 8.03–7.90 (m, 4H), 7.60–7.52 (m, 11H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 9H), 4.78–4.74 (m, 4H), 3.46 (s, 6H), 3.02–2.99 (m, 2H), 2.89–2.85 (m, 2H), 1.64 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 1.60 (d, J = 5.6Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR(CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 166.6, 158.23, 158.19, 153.6, 147.56, 147.49, 133.3, 133.2, 132.41, 130.9, 129.52, 129.46, 129.41, 129.39, 128.89, 128.81, 128.79, 128.45, 128.44, 127.81,127.69, 123.2 (q, J = 292.0 Hz, CF3), 123.7, 122.4, 121.9, 121.8, 120.9, 120.8, 112.1, 108.2, 84.0 (q, J = 25.9 Hz, C-CF3), 83.8 (q, J = 26.3 Hz, C-CF3), 55.18, 52.27, 51.66, 39.5, 39.2, 33.6, 33.1, 30.9, 23.4, 23.3. 19F NMR (CDCl3, 470 MHz) δ −68.79, −68.81. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C27H22F3N2O7S [M-H]+, 575.1105; found: 575.1118.

General Procedure for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS).

Peptides were synthesized using an automated solid-phase peptide synthesizer (PS3, Protein Technologies Inc., Memphis, TN) employing Fmoc/HCTU-based chemistry. Fmoc-Met-Wang or Fmoc-Ala-Wang resin (0.03 mmol) was placed in the reaction vessel and deprotected twice using 20% piperidine in dimethylformamide (DMF) for 5 min each time. Four equivalents of amino acids and HCTU were activated in 0.4 M N-methylmorpholine (NMM) for 1 min before adding to the resin. Standard incubation time for each coupling was 20 min. Manual coupling of caged Fmoc-Cys derivatives was performed in a polypropylene filter syringe equipped with a polypropylene stopcock. Four equivalents of the protected cysteine were activated with 4 equivalents of HCTU in 1 mL 0.4 M NMM for 10 min before adding to the resin. The reaction completion was tested every hour using a ninhydrin assay.30 All caged Fmoc-Cys derivatives required 4 h for completion. Once the ninhydrin assay confirmed the absence of any free amines, the resin was washed thoroughly with DMF before placing back on the synthesizer and resuming the synthesis as previously described. Once complete, approximately half of the resin was transferred to a syringe filter and washed three times with CH2Cl2. Global deprotection and resin cleavage was accomplished via treatment with 5 mL reagent K (82.5% TFA, 5% phenol, 5% water, 5% thioanisole, and 2.5 % ethanedithiol) for 2 h. Cleaved peptides were precipitated with Et2O and centrifuged before decanting the Et2O layer (repeated 3 times total). The resulting crude peptide was dried via a stream of dry N2, then dissolved in 8 mL of a mixture of H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA, aided by sonication. The solution was filtered using a 0.2 μm PTFE filter and then purified using preparative reverse-phase (RP)-HPLC. Once pure peptides were obtained, their concentrations were quantified in solution using the ε350 value measured for the caged Fmoc-Cys derivatives (1, 2 or Fmoc-Cys(NV)-OH). Stock solutions were generated by dilution in H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA to a final concentration of 300 μM and stored at −20 °C.

NH2-YIIKGVFWDPAC(MeO-NDBF)VIA-OH (10).

ESI-MS calcd for C98H136N18O23S [M+2H]2+ 982.9883, found 982.9879. 33.6 mg were obtained after cleavage of approximately half of the resin.

NH2-YIIKGVFWDPAC(NDBF)VIA-OH (11).

ESI-MS. calcd for C97H134N18O22S [M+2H]2+ 967.9854, found 967.9826. 19.0 mg were obtained after cleavage of approximately half of the resin.

NH2-YIIKGVFWDPAC(NV)VIA-OH (12).

ESI-MS. calcd for C92H134N18O23S [M+2H]2+ 945.9829, found 945.9790. 10.5 mg were obtained after cleavage of approximately half of the resin.

NH2-KKKSKTKC(MeO-NDBF)VIM-OH (15).

ESI-MS. calcd for C71H121N17O18S2 [M+2H]2+ 781.9253, found 781.9243. 17.7 mg were obtained after cleavage of approximately half of the resin.

NH2-KKKSKTKC(NDBF)VIM-OH (16).

ESI-MS. calcd for C70H119N167O17S2 [M+2H 2+ 766.9200, found 766.9193. 9.0 mg obtained after cleavage of approximately half of the resin.

Model Tripeptide NH2-GC(NDBF)F-OH (18).

Peptide 18 was synthesized manually on a 0.01 mmol scale using the conditions described in the General Procedure for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) section. Compound 2 (6 equiv) along with PyBOP, HOAT, and DIEA (6 equiv each) were dissolved in DMF at 50 mM concentration and coupled to Phe-Wang resin for 1 h. After synthesis, a small amount of the peptide was cleaved from resin using 95% TFA with 2.5% CH2Cl2 and 2.5% H2O for 20 min. The solvent was then removed using a gentle stream of dry N2, which took approximately 40 min. The resulting residue was brought to dryness using a rotary evaporator. DMF (200 μL) was used to dissolve the peptide and the solution was filtered using a GHP filter before acquiring a LC-MS chromatogram with single ion monitoring to observe the epimerized product. The gradient consisted of an isocratic hold at 1% buffer A for 10 min to fully remove the DMF, followed by a 1–100% gradient over 100 min (1% increase per min). The remaining resin was incubated in 6 mL of 20% piperidine in DMF for 2 h to simulate 12 coupling steps in the synthesis of a full dodecapeptide and another LC-MS chromatogram was obtained as before to probe for epimerization. ESI-MS. calcd for C12H29N4O7S [M+H]+ 565.2, found 565.2.

Coupling Optimization on Complete Peptides to Reduce Epimerization.

Peptide 10 was synthesized on a 0.01 mmol scale using procedure described in the General Procedure for Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) section. However, compound 1 (4 equiv) was coupled using 4 equiv of N,N’-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) and 6-Chloro-1-hydroxybenzotriazole (Cl-HOBT) in DMF at 150 mM concentration for 1 h. Peptide 15 was synthesized on the same scale, but using 4 equiv of Benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP), 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAT), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) for 30 min. LC-MS chromatograms with single ion monitoring were acquired using an isocratic hold at 1% buffer A for 5 min, followed by a 1–100% gradient over 100 min (1% increase per min).

General Procedure for UV Photolysis of Caged Peptides in Rayonet Reactor.

Peptides were diluted in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 containing 1 mM DTT to a final concentration of 100 μM. The solutions were transferred into the quartz tubes and irradiated in using 14 × 350 nm bulbs (14 W, RPR-3500 Å). Aliquots (50 μL) were withdrawn at various intervals ranging from 0 to 30 sec (up to 240 sec for peptide 12), and 40 μL were subjected to LC-MS analysis. It is important to note that photolysis in H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA or in PB buffer containing 1 mM DTT led to production of compounds with an m/z corresponding to the desired free thiols + 32 mass units, believed to be the corresponding sulfinic acid (Figure S4A–B). Photolysis in PB buffer containing 15 mM DTT showed only the desired free thiols (Figure S4C–D).

General Procedure for UV Photolysis of Caged Peptides in LED Reactor.

Photolysis was conducted in a home-built LED reactor equipped with 8 × 350 nm LEDs (FoxUV, 5.5mm) evenly spaced in a radial arrangement. A round quartz tube (10 × 50 mm) with 1 mm wall thickness was positioned in the middle of the reactor. 200 μL of solution was used for photolysis, resulting in an irradiated surface area of 1 cm2. Kinetic analyses were performed using caged peptides diluted in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4 containing 15 mM DTT to a final concentration of 10 μM. At this concentration, > 90% transmittance occurs, thereby minimizing any inter-filter effect. The samples were irradiated for varying amounts of time ranging from 0 to 90 sec (180 to 1080 for peptide 12), and then 100 μL aliquots were subjected to LC-MS analysis with UV monitoring at 350 nm and MS scanning over a 500–2000 m/z window. The gradient was isocratic at 1% buffer A for 5 min, followed by a 1–100% gradient over 10 min (10% increase per min). Peaks exhibiting the m/z of the caged peptide were integrated in the UV chromatogram, and the amount of remaining caged peptide was calculated using the formula: Remaining SM (%) = (Peak area after irradiation)/(Peak area of unirradiated sample)*100. The quantum yield of uncaging (Φ) in mols/ein was calculated using the relationship Φ = (Iσt90)−1, where I is the irradiation intensity in ein·cm−2.sec−1, σ is the decadic extinction coefficient in cm2·mol (1000·ε), and t90 is the irradiation time in seconds required to achieve 90% uncaging.31 The intensity (I) at 350 nm was measured to be 1.93E-09 ein·cm−2.sec−1 via actinometry using 6 mM potassium ferrioxalate as a standard.32

Laser apparatus for Two-Photon (TP) irradiation:

For the two-photon kinetic experiments, a home-built regeneratively amplified Ti:Sapphire laser operating at 1 kHz with the pulse power maintained between 68 – 76 mW centered around 800 nm was used. Each pulse had a Gaussian profile with a full width at half maximum of 80 fs. This system is described in detail elsewhere.33 The beam was sent through a 35 cm focusing lens and then through the sample. Samples (30 μL) were irradiated in a quartz microcuvette (Starna 16.10-Q-10/Z15, 1 mm × 1 mm sample window, 10 mm path length) 15 cm after the focal plane of the lens.

General Procedure for Two-Photon Photolysis of Caged Peptides at 800 nm.

Samples were irradiated in a 30 μL quartz cuvette (Starna Cells Corp.). The TP action cross-sections for 10, 11, and 15 were measured by comparing the photolysis rates of the peptides with that of BhcOAc as a reference (δu = 0.45 at 800 nm). Aliquots (30 μL) containing peptides (100 μM in H2O/CH3CN (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA) were irradiated with the 800 nm laser system for varying amounts of time, ranging from 2.5 to 30 min. Each sample was analyzed by LC-MS using the previously described method. BhcOAc photolysis experiments were conducted in the same manner using a 100 μM solution in 50 mM PB, pH 7.4. Reaction progress data were analyzed as described above, and the first-order decay constants for the two compounds were calculated from by fitting to a first order exponential decay process.18

UV and TP-Triggered Enzymatic Reactions.

A 7.5 μM solution of peptide 10 was prepared in prenylation buffer (50 mM PB, pH 7.4, 15 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ZnCl2, 20 mM KCl, and 22 μM FPP) and divided into three 50 μL aliquots. Yeast PFTase was added to the first aliquot to give a final concentration of 50 nM, but the resulting sample was not subjected to photolysis. The second aliquot was irradiated in the absence of yeast PFTase, while the third sample was supplemented with yeast PFTase (50 nM) and then photolyzed with UV light using the Rayonet reactor. UV photolysis was conducted for 30 sec at 350 nm as described above using three light bulbs. Each sample was incubated for 90 min at rt to allow the enzymatic reaction to proceed and then the entire sample was analyzed by LC-MS using the gradient described above, and detected with single ion monitoring (SIM) for the [M+H]+1, [M+2H]+2, and [M+3H]+3 charged states for the caged peptide (1967.9, 982.9, 655.6), the free thiol peptide (1694.9, 847.4, 565.3), and the farnesylated peptide (1900.1, 950.5, 634.0), respectively. The TP experiments were performed in an analogous manner using peptide 10 at identical concentrations as the UV experiment, but using 30 μL aliquots (due to the 30 uL cuvette size). Samples used initially to generate either the free thiol (13) or farnesylated product (14) were irradiated for 10 min. Samples used to generate the farnesylated product as a function of time were irradiated for varying amounts ranging between 0 and 25 min. The percent remaining starting material was determined by integrating the SIM peaks for the starting peptide (10) and farnesylated product (14) and inputting into the following formula: Remaining SM (%) = (SIM of 10)/[(SIM of 10) + (SIM of 14)]*100.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Mosher’s amides of NDBF-protected cysteine for subsequent stereochemical analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Matt Hammers and Andrew Healy for valuable consultations. We acknowledge the Mass Spectrometry Core Facility of the Masonic Cancer Center, a comprehensive cancer center designated by the National Cancer Institute, supported by P30 CA77598, where the LC-MS/MS analysis was performed. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, including R01 GM084152, R21 CA185783 and NSF/CHE 1905204 to M.D.D.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Figures; Tables of ions observed via LC-MS/MS for protected peptides; 1H NMR, 13C NMR and 19F NMR, for all new compounds; ESI-MS and analytical HPLC chromatograms for reported peptides. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Haugaard N Reflections on the Role of the Thiol Group in Biology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2000, 899, 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Couvertier SM; Zhou Y; Weerapana E Chemical-proteomic strategies to investigate cysteine posttranslational modifications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Prot. Proteom 2014, 1844, 2315–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Poole LB The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2015, 80, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Klán P; Šolomek T; Bochet CG; Blanc A; Givens R; Rubina M; Popik V; Kostikov A; Wirz J Photoremovable Protecting Groups in Chemistry and Biology: Reaction Mechanisms and Efficacy. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 119–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shao Q; Xing B Photoactive molecules for applications in molecular imaging and cell biology. Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 2835–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Silva JM; Silva E; Reis RL Light-triggered release of photocaged therapeutics - Where are we now? Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 298, 154–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Uprety R; Luo J; Liu J; Naro Y; Samanta S; Deiters A Genetic encoding of caged cysteine and caged homocysteine in bacterial and mammalian cells. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1793–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ellis-Davies GCR Two-Photon Uncaging of Glutamate. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 2019, 10, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Isidro-Llobet A; Álvarez M; Albericio F Amino Acid-Protecting Groups. Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 2455–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kaplan JH; Forbush B; Hoffman JF Rapid photolytic release of adenosine 5’-triphosphate from a protected analog: utilization by the sodium:potassium pump of human red blood cell ghosts. Biochemistry 1978, 17, 1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chang C -y.; Niblack, B.; Walker, B.; Bayley, H. A photogenerated pore-forming protein. Chem. Biol 1995, 2, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).DeGraw AJ; Hast MA; Xu J; Mullen D; Beese LS; Barany G; Distefano MD Caged Protein Prenyltransferase Substrates: Tools for Understanding Protein Prenylation. Chem. Biol. Drug Des 2008, 72, 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nguyen DP; Mahesh M; Elsässer SJ; Hancock SM; Uttamapinant C; Chin JW Genetic Encoding of Photocaged Cysteine Allows Photoactivation of TEV Protease in Live Mammalian Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 2240–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Karas JA; Scanlon DB; Forbes BE; Vetter I; Lewis RJ; Gardiner J; Separovic F; Wade JD; Hossain MA 2-nitroveratryl as a photocleavable thiol-protecting group for directed disulfide bond formation in the chemical synthesis of insulin. Chemistry 2014, 20, 9549–9552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Furuta T; Wang SSH; Dantzker JL; Dore TM; Bybee WJ; Callaway EM; Denk W; Tsien RY Brominated 7-hydroxycoumarin-4-ylmethyls: photolabile protecting groups with biologically useful cross-sections for two photon photolysis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1193–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Momotake A; Lindegger N; Niggli E; Barsotti RJ; Ellis-Davies GC The nitrodibenzofuran chromophore: a new caging group for ultra-efficient photolysis in living cells. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhu Y; Pavlos CM; Toscano JP; Dore TM 8-Bromo-7-hydroxyquinoline as a Photoremovable Protecting Group for Physiological Use: Mechanism and Scope. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 4267–4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Mahmoodi MM; Abate-Pella D; Pundsack TJ; Palsuledesai CC; Goff PC; Blank DA; Distefano MD Nitrodibenzofuran: a One- and Two-Photon Sensitive Protecting Group that is Superior to Brominated Hydroxycoumarin for Thiol Caging in Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5848–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wosnick JH; Shoichet MS Three-dimensional Chemical Patterning of Transparent Hydrogels. Chem. Mater 2007, 20, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kotzur N; Briand B; Beyermann M; Hagen V Wavelength-Selective Photoactivatable Protecting Groups for Thiols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 16927–16931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Abate-Pella D; Zeliadt NA; Ochocki JD; Warmka JK; Dore TM; Blank DA; Wattenberg EV; Distefano MD Photochemical Modulation of Ras-Mediated Signal Transduction using Caged Farnesyltransferase Inhibitors: Activation via One- and Two-Photon Excitation. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Aujard I; Benbrahim C; Gouget M; Ruel O; Baudin J-B; Neveu P; Jullien L o-Nitrobenzyl Photolabile Protecting Groups with Red-Shifted Absorption: Syntheses and Uncaging Cross-Sections for One- and Two-Photon Excitation. Chemistry – A European Journal 2006, 12, 6865–6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).LoPachin RM; Gavin T Molecular mechanisms of aldehyde toxicity: a chemical perspective. Chem. Res. Tox 2014, 27, 1081–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Xue C-B; Becker JM; Naider F Efficient Regioselective Isoprenylation of Peptides in Acidic Aqueous Solution using Zinc Acetate as Catalyst. Tetrahedron. Lett 1992, 33, 1435–1438. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nicolaou KC; Estrada AA; Zak M; Lee SH; Safina BS A Mild and Selective Method for the Hydrolysis of Esters with Trimethyltin Hydroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Molina RS; Tran TM; Campbell RE; Lambert GG; Salih A; Shaner NC; Hughes TE; Drobizhev M Blue-Shifted Green Fluorescent Protein Homologues Are Brighter than Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein under Two-Photon Excitation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 2548–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Palsuledesai CC; Distefano MD Protein prenylation: enzymes, therapeutics and biotechnology applications. ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kohl NE; Omer CA; Conner MW; Anthony NJ; Davide JP; deSolms SJ; Giuliani EA; Gomez RP; Graham SL; Hamilton K Inhibition of farnesyltransferase induces regression of mammary and salivary carcinomas in ras transgenic mice. Nat. Med 1995, 1, 792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Berndt N; Hamilton AD; Sebti SØM Targeting protein prenylation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 775–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kaiser E; Colescott RL; Bossinger CD; Cook PI Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal. Biochem 1970, 34, 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tsien RY; Zucker RS Control of cytoplasmic calcium with photolabile tetracarboxylate 2-nitrobenzhydrol chelators. Biophys, J 1986, 50, 843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hatchard CG; Parker CA; Bowen EJ A new sensitive chemical actinometer - II. Potassium ferrioxalate as a standard chemical actinometer. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1956, 235, 518–536. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Underwood DF; Blank DA Ultrafast Solvation Dynamics: A View from the Solvent’s Perspective Using a Novel Resonant-Pump, Nonresonant-Probe Technique. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 956–961. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.