Abstract

Endogenous retrovirus (ERV) are remnants of ancient retroviruses that have been incorporated into the genome and evidence suggests that they may play a role in the etiology of T1D. We previously identified a murine leukemia retrovirus-like ERV whose Env and Gag antigens are involved in autoimmune responses in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. In this study, we show that the Gag antigen is present in the islet stromal cells. Although Gag gene transcripts were present, Gag protein was not detected in diabetes-resistant mice. Cloning and sequencing analysis of individual Gag genes revealed that NOD islets express Gag gene variants with complete open-reading frames (ORFs), in contrast to the diabetes-resistant mice, whose islet Gag gene transcripts are mostly non-ORFs. Importantly, the ORFs obtained from the NOD islets are extremely heterogenous, coding for various mutants that are absence in the genome. We further show that Gag antigens are stimulatory for autoreactive T cells and identified one islet-expressing Gag variant that contains an altered peptide ligand capable of inducing IFN-gamma release by the T cells. The data highlight a unique retrovirus-like factor in the islets of the NOD mouse strain, which may participate in key events triggering autoimmunity and T1D.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Endogenous retrovirus, Gag, Microvesicles, Non-obese diabetic mouse, Type 1 diabetes, T cells

1. Introduction

Among the immune cells infiltrating the islets in Type 1 diabetes (T1D), T cells are the key players controlling the progress of the disease (1), as supported by a characteristics of antigen-driven clonal activation (2,3). However, most of the islet-infiltrating T cells show low affinity for the candidate islet antigens such as insulin and glutamic acid decarboxylase -65 (GAD65) (4–7). The mechanism to activate these self-reactive T cells to execute effector function and islet destruction remains unclear. It is hypothesized that there may be an early triggering event that selectively alters islet antigens and/or their enzymatic digestion or peptide presentation, which may eventually lead to induction of effector rather than regulatory T cells (8,9). Since almost all NOD mice develop insulitis at young age (2-3 weeks), the process of islet development was suggested to be the trigger (10,11). If so, the NOD mouse strain must have produced some pro-inflammatory antigens that can activate innate immune cells and signals (12,13). Interestingly, type 1 interferons (IFNs) and IFN-inducible genes are among the earliest innate signatures during the islet inflammatory response (12,14), suggesting a possible involvement of virus or viral antigens.

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) can activate innate and adaptive immune responses (15,16). It is estimated that 5-8% of mouse and human genomes are remnant sequences of ancient retrovirus (17). Many of these ERVs have genetic organization similar to that of exogenous retroviruses, with two long terminal repeats (LTRs), and four basic retroviral genes; gag, pro, pol, and env. Activated ERVs may produce viral RNA, antigens or non-replicating viral particles to cause autoimmunity (18). Indeed, human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) are associated with several autoimmune diseases. For example, HERV-W was initially called “Multiple Sclerosis retrovirus” due to its isolation from the brains of multiple sclerosis patients (19). Systemic lupus erythematosus has been linked to the loss of HERV-K(C4)(HML-10) genomes (20), and patients develop autoantibodies specific for HERV-K peptides (21). With respect to a viral etiology in the development of T1D, a HERV called K18-like HERV was isolated from the islets of patients with TID although there remains controversy on whether this ERV is detectable in patient sera (22,23). Another HERV-K family virus HERV-K(C4) has also been implicated in TID, but intriguingly, this ERV appears inhibitory to T1D (24). Recent studies suggested that a different endogenous virus, HERV-W that is highly homologous to a multiple sclerosis-associated retrovirus (19), may also involve in T1D (25,26). In NOD mice, a murine leukemia retrovirus (MuLV)-like ERV was identified. Gaskins et al. observed that NOD islets contain defective type C retroviral particles (27), and the retroviral antigens were expressed in the islets (28). Also, antibodies specific for a MuLV Env could be isolated from young NOD mice (29), and indeed, an ecotropic MuLV-like ERV, emv30, can replicate and cause primary cancer in immune-deficient NOD mice (30).

Apart from detection of these viruses or their components in T1D patients or animal models of TID, there are no mechanistic studies that directly link the ERVs or their antigens to the development of TID. We originally found that the Gag antigen was enriched in microvesicles released from an insulinoma cell line Min6 and could induce autoreactive T cells (31). We also discovered that primary islet mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can release similar highly immune-stimulatory microvesicles and importantly, that the Gag antigen is expressed in the MSCs (32). In the present study, we studied Gag expression in the islets and analyzed the DNA sequences and we surprisingly found many different Gag gene variants in the islets. We further evaluated these variants and peptides in stimulating T cells to release IFN-γ. Our data indicate an unexplored endogenous retroviral event involving in generation of Gag variants, which may be the key to induce autoreactive T cells.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Mice and Peptides

NOD/ShiLtJ (NOD), C57BL/6 (B6), NOD.B10sn.H2b/J (NOD.H2b), B6NOD-(D17Mit21-D17Mit10)/LtJ (B6.I-Ag7), NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid (NOD.scid) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). A transgenic mouse, NOD.BDC-2.5 (BDC-2.5), that expresses a diabetes-causative TcR was obtained from Dr. Linda Sherman in Scripps Research (La Jolla, CA). To retain T1D susceptibility, new NOD breeders were purchased after the colony was maintained for two generations in the animal facilities of Scripps Research (La Jolla, CA) and Biomedical Research Institute of Southern California (BRISC, Oceanside, CA). Experimental protocols using the various mouse models were conducted with approvals from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Scripps Research and BRISC. Peptides were synthesized by Synthetic Biomolecules (San Diego, CA) or GenScripts (Piscataway, NJ) with above 90% purity and with no amide groups. Peptides were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 20 mg/ml and stocks prepared by dilution in water to 2 mg/ml. The stock peptides were further diluted in complete culture media for culturing with splenocytes.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Mouse pancreatic tissues were snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc.) and 7μm sections cut for immunostaining. Tissue sections were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, blocked with 10% FCS/PBS at room temperature (RT) for 2 hours prior to the staining. For sections that were stained by the avidin/biotin system, an additional blocking step with excess Avidin and Biotin (SP-2001, Vector Lab) was used. Primary antibodies (2-5 μg/ml) were diluted in 1% BSA/PBS and incubated with the tissue sections overnight at 4°C. The excess unbound antibodies were washed off with 0.025% Triton X100 in PBS and the sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity. The tissues were then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:200) labeled with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP) diluted in 1% mouse serum at RT for 1 hr. After washing, the sections were incubated with ImmPACT AEC (SK-4200, Vector Lab) and/or BCIP/NBT (SK-5400, Vector Lab) substrates. Counter staining with Hematoxylin (5 minutes at RT) was performed as required. The slides were then mounted and sealed for observation. The primary antibodies used in this study were rat anti-Gag mAb R187 (33), Biotin-labelled anti-CD105 (clone MJ7/18, BioLegend) and Biotin-labelled anti-Sca-1 (clone D7, BioLegend). The secondary antibodies used were anti-rat Ig-HRP (Cat#A10549, Invitrogen), AP-labelled secondary reagent for detecting rat IgG (AK5004, Vector Lab), and Avidin-HRP (Cat#RPN1231V, GE Healthcare).

2.3. Cloning and Sequencing Islet-Expressing Gag Genes

Islets were collected from 8-week-old NOD female mice (34). For other mouse strains, pancreases were minced and digested in 1 mg/ml of collagenase for islet isolation. Total RNA was purified from 200-300 islets using an RNA kit (Qiagen), followed by DNase treatment; cDNA synthesis was performed using the random primers provided in the kit (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific). To amplify Gag genes, a pair of DNA primers that bind to conserved regions of different ERV Gag genes were designed as follows: Forward F225: 5’-ACACCCGGATCAGGTCCCATA-3’; Forward F371: 5’-CCCGATCTGCCCTTTACCC-3’; Reverse R1060: 5’-CTTTTACCTTGGCCAAATTGG-3’. The primers allowed the amplification of partial sequences of Gag genes to yield PCR fragments of 836bp or 690bp, respectively. Amplified PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel. To identify Gag gene variants expressed in the islets, the PCR products were purified (Qiagen) and cloned into pCR2.1 plasmid using a TA-cloning kit (Invitrogen), followed by DNA sequencing (Eton Bioscience). Sequence alignment was performed using Vector NTI software or NCBI BLAST tools. For cloning the full-length Gag genes, the islet cDNA was amplified using following primers that bind to the N’- and C’-termini of the Gag gene: Forward: 5’-ATGGGACAGACCGTAACTACC; Reverse: 5’-CTAGTCACCTAAGGTTAGGAGGG.

2.4. Purification of Microvesicles

All cell culture for harvesting microvesicles was performed in microvesicle-free medium that was prepared by pre-centrifuging fetal calf serum at 100,000 g for 90 mins to remove serum derived microvescicles. Microvesicles were harvested from spent medium of Min6 insulinoma cells, NOD and B6 islet derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The primary islet MSCs were derived from freshly isolated mouse islets and cultured in complete high-glucose DMEM media (32). The spent medium was collected and stored at 4°C (< 4 weeks) for harvesting the microvesicles. The islets derived primary cultures were used for no more than 10 generations for harvesting microvescicles. Microvesicles were isolated by a 3-step ultracentrifugation process: 1) The spent medium was first spun at 300 g for 20 mins to remove large cellular debris, 2) The supernatant was then spun at 10,000 g for 20 mins at 4°C to remove large microparticles, and 3) The supernatant was spun at 100,000 g for 60 mins at 4°C (Optima XPN-100, Beckman Coulter) to harvest the microvesicles. The pellets from the last ultracentrifugation step was washed by re-suspending in PBS and re-centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60mins. The microvesicle pellet was resuspended in PBS in a volume that was 1:300 of the original volume of the culture supernatants. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.5. Recombinant Gag protein (rGag)

The Gag genes were cloned from the Min6 insulinoma cells or from the islets of prediabetic NOD mice. Sequencing analysis confirmed that the Gag gene expressed in the Min6 cells is identical to a published sequence of an ecotropic MuLV (DQ366147). All the Gag genes (26 total) cloned from NOD mice are highly homologous (>90%) to an ERV found on chromosome 4 at position from 108152234 to 108153844 (CS4.108x). These Gag genes were then subcloned into a pLV lentiviral expression plasmid containing two 6xHis tags and a signal peptide that allowed secretion of the Gag protein (Biosettia, San Diego). The pLV plasmids were then transfected into a packaging cell line to produce viruses, which were used to infect 293T cells to produce rGag. The secreted Gag recombinant protein was purified using Ni-NTA resin and eluted off the column using 500 mM of imidazole, followed by extensive dialysis in PBS. The protein was purified to above 90% purity and confirmed by Coomassie blue staining. Protein concentration was determined at an absorbance of 280nm.

2.6. Virus-like Particles (VLPs)

The Gag gene from the Min6 cells was cloned into a plasmid pMV-2024 (Altravax, Inc) at the PstI/XbaI sites. The ERV Env gene was synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) using the endogenous MuLV sequence DQ366147 as reference and cloned at EcoRI/XhoI sites of the pCAGGS plasmid. To produce VLPs, 293T cells were transfected with the Gag and/or Env expression plasmids using polyethylenimine (PEI) (35). The transfected cells were incubated with 25 ml of 1% FCS exosome-free DMEM medium for 24 – 48 hours. VLPs were isolated from supernatants using the same 3-step ultracentrifugation process described above for purifying the microvesicles. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

2.7. Cytokine Analysis

Splenocytes from NOD mice (106 cells/200μl/well) were cultured with or without microvesicles for 48 hours. Culture supernatants were harvesting and stored at −20°C until ready for testing. Cytometric bead arrays (CBA) (BD Biosciences, San Jose) were used to analyze inflammatory cytokines or chemokines (IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-12p70), or T cell cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α). Concentrations of the various cytokines/chemokines were extrapolated from standard curves by using respective recombinant proteins that were supplied with the kit.

2.8. Flow Cytometry (FACS)

Cultured MSCs were detached by incubating with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution at 37°C for 5 minutes. Single cells suspension was obtained by pass the detached MSCs through a 0.45μm cell strainer. For FACS analysis of islet cells, fresh isolated islets were treated with 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA for 5 min at 37°C, followed by pipetting to separate single cells. The cells are then incubated with purified anti-FcγR (clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences) before staining with fluorescent antibodies, including CD45 (clone 30-F11, BD Biosciences), CD31 (clone MEC13.3, BioLegend), and CD105 (clone MJ7/18, BioLegend) and Sca-1 (clone D7, BioLegend). Samples were analyzed on a BD LSR II or a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences), and cell sorting was performed on a FACS Aria II flow cytometer.

2.9. Western Blotting

Cell lysates were prepared and resolved by SDS-PAGE as previously described (36). Purified microvesicles suspended in PBS were tested directly by the SDS-PAGE analysis. All samples were mixed in concentrated SDS loading sample buffer and denatured at 95°C for 10 minutes. After transferring the resolved proteins onto a nitrocellulose membrane, immuno-blotting was performed using 1 μg/ml of purified mAbs or 1:1000 dilution of polyclonal antibodies, followed by the respective secondary HRP-labeled anti-IgG (Amersham, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The protein bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham). Antibodies used in this study include a goat-anti-MuLV Gag p15 antiserum (CRL-1889, ATCC), anti-Gag mAb R187 (Courtesy of Dr. Leonard Evans) and anti-HSC70 (SPA-815, Stressgen, Enzo Life Sciences).

2.10. Diabetes Incidence and Statistical Analysis

Paraffin-embedded mouse pancreatic tissues were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for morphological examination and for assessing lymphocyte infiltration (Pacific Pathology, San Diego, CA and Histology Core Laboratory at Scripps Research). For diabetes incidence, blood glucose was measured weekly. Mice with two consecutive measurements higher than 250 mg/dL were considered diabetic. Survival analysis was performed using Log-rank test.

2.11. Data and Resource Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The sequencing data of the full-length Gag genes are included in the online supplementary files and their FASTA formats are available from the corresponding author. Additional sequencing data analyzed in Fig. 1D are also available upon request. Mouse ERV Gag sequences and ORFs were obtained by blatting the genome (GRCm38/mm10) with a MuLV Gag gene (GenBank: DQ366147.1) using the server <http://genome.ucsc.edu>. The anti-Gag mAb R187 was provided by Dr. Leonard Evans and restriction may apply to the availability of this reagent. Expressing vectors for the Gag genes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FIG. 1.

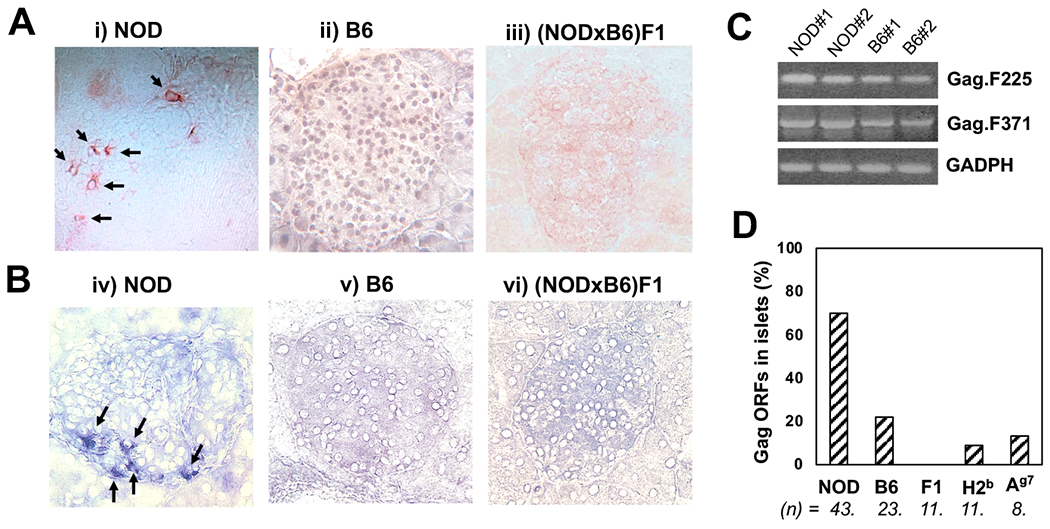

Detection of Gag antigen in pancreatic islets. A and B: Frozen sections of pancreas from female NOD (i&iv), B6(ii&v) and (NODxB6)F1 (iii&vi) mice (8-12 week-old) were stained with R187 anti-Gag mAb, followed by HRP-labeled (A) or AP-labeled (B) anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies and color development using AEC (A) or BCIP/NBT (B) substrate, respectively. C: RT-PCR was performed using total RNA (genomic DNA-free) from isolated islets from female NOD or B6 mice (8-12 weeks) to detect Gag gene messages. D: Cloning and sequencing of Gag gene PCR products in (C). The DNA sequences were aligned to a Gag gene cloned from Min6 insulinoma to identify ORFs. The numbers (n) of total sequenced clones for each of the mouse strains, NOD, B6, (NODxB6)F1 (F1), NOD.H2b (H2b) and B6.I-Ag7(Ag7) are shown, and the frequency of ORFs is calculated.

3. Results

3.1. NOD but Not Diabetes-resistant Mouse Islets Express a MuLV-like ERV Gag Antigen.

To examine the expression of ERV antigens in pancreatic islets, we used a monoclonal antibody (mAb) R187, which reacts with an epitope on Gag protein that is shared by 9 out of 10 different viruses including both exogenous and endogenous MuLV strains (33). The mAb recognizes a conserved structure of p30 subunit of Gag protein. Cryosections of pancreas from diabetes-susceptible or resistant mice were examined by IHC staining. Fig. 1 shows individual islets of NOD (i&iv), B6 (ii&v), and (NODxB6)F1 (iii&vi) mouse pancreas. Either HRP-labeled (Fig. 1A) or AP-labeled (Fig. 1B) secondary antibodies were used to visualize the primary antibody R187 staining using a red or a blue substrate, respectively. In both cases, we observed a strong positive staining of NOD islets as indicated by the arrows, but the staining was absent in islets of other mouse strains. The staining pattern shows that: 1) the Gag protein is expressed in cytoplasm and cell membrane but was absent from the nucleus, 2) not all islets were positive for Gag, 3) in the islets that were positive for Gag, very few positive cells were observed, and apparently, the number of positive cells was not correlated with the level of insulitis, 4) positively-stained cells were also observed at perivascular/periductal area outside of islets. To confirm that NOD islets express Gag genes, we designed DNA primers binding to conserved regions that are shared among different ERV Gag genes in the genome. Using RT-PCR method, we analyzed fresh islet RNA and cDNA samples. Surprisingly, the PCR data showed that all the islet samples including those from resistant mice were positive for Gag gene transcripts (Fig. 1C). Therefore, both diabetes-susceptible and resistant mice express Gag gene transcripts in their pancreatic islets, but only NOD expresses Gag protein in the islets. To investigate whether a unique Gag gene(s) was expressed in the NOD, we cloned the PCR fragments and performed Sanger sequencing analysis of the individual clones. Out of 43 clones sequenced from the NOD islet sample, we noted that 30 sequences (70%) were in the correct open-reading frame (ORFs) (Fig. 1D). In contrast, only 22% of the sequences cloned from the B6 islets were ORFs. The frequencies of ORFs identified for the other diabetes-resistant strains were also low: F1 mice had 0% (n=11), NOD.H2b mice had 9% (n=11), and B6.Ag7 had 13% (n=8), indicating that untranslatable Gag gene transcripts or non-ORFs are commonly present in the islets regardless of insulitis and diabetes. Therefore, increased number of ORFs of Gag genes correlates with the expression of Gag protein in NOD islets.

3.2. Islet Stromal Cells but Not Hematopoietic Cells Express the ERV Gag Antigen.

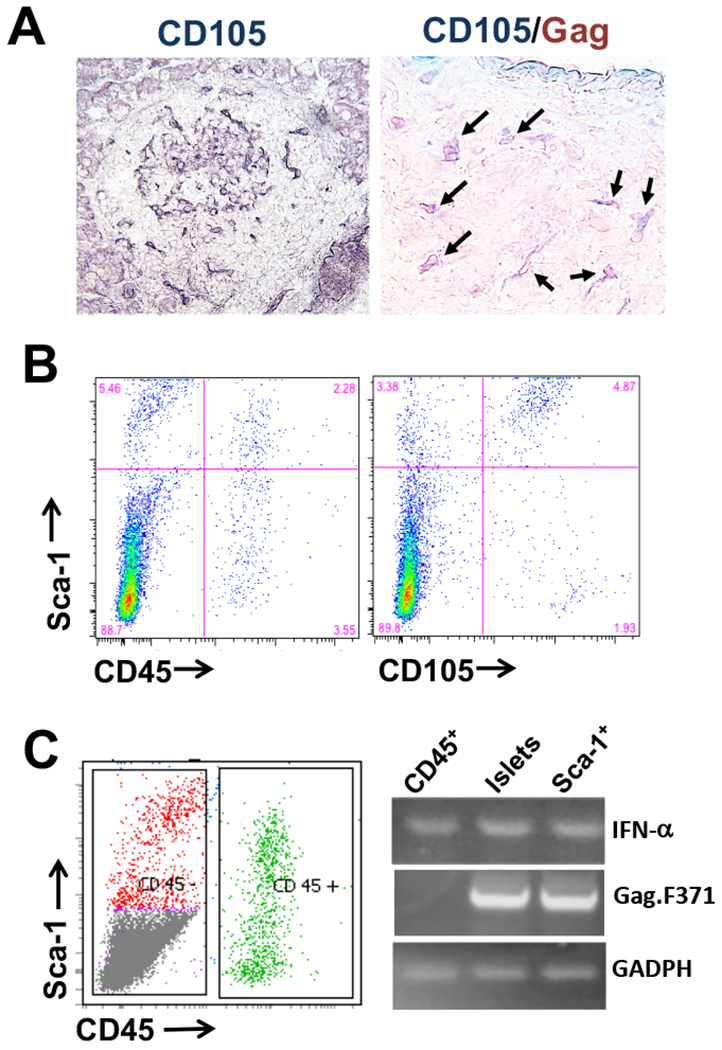

To characterize the islet Gag-expressing cells, we stained the cryosections with antibodies to stromal cell surface markers. In prediabetic NOD islets, CD105+ stromal cells were found within the islets, often co-localized with the cells expressing Gag, whereas, the surrounding lymphocyte-infiltrated areas were negative for Gag and were rarely positive for CD105 (Fig. 2A left). In contrast, in the absence of lymphocyte infiltration, CD105+ stromal cells were often present at the periphery of an intact islet (32). By co-staining for both CD105 and Gag, we observed that majority of the CD105+ stromal cells were not expressing Gag. However, in certain islets, double positive cells, expressing both CD105 (Blue) and Gag (red), were common (Fig. 2A right). Therefore, there was heterogeneity not only within the stromal cell population but also between different islets. With flow cytometry method, we observed that both CD45-positive hematopoietic cells and CD45-negative stromal cells contain stem cells that express Sca-1 and that majority (>70%) of the CD105+ stromal cells are also Sca-1-positive (Fig. 2B), indicating a relationship of the Gag-expressing cells with the origin of stem cells. This origin was further supported using sorted islet cell subsets to perform RT-PCR. Fig. 2C demonstrated that Gag genes are expressed in the CD45−/Sca-1+ subset, but not the CD45+ subset. Taken together, our data suggest that the islet stromal/stem cells, but not the infiltrating hematopoietic cells, express the retroviral antigen.

FIG. 2.

Identification of islet cell subset(s) expressing Gag antigen. A: Frozen sections of pancreas from female NOD mice were stained with biotin-labeled anti-CD105 antibody, followed by AP-Avidin as secondary and BCIP/NBT were used as substrate (left); or the section were stained with both biotin-labeled anti-CD105 and anti-Gag R187 antibodies, followed by with AP-Avidin and HRP-anti-rat IgG and then followed with BCIP/NBT and AEC substrates (right). B: Islet cell suspensions from female NOD mice (8-12 weeks) were stained with fluorescent-labeled antibodies shown. C: Cell sorting was performed using the stained cells in (B) to isolate CD45+ or CD45−/Sca-1+ islet cell subsets (left). RT-PCR was performed using total RNA (genomic DNA-free) from the sorted cells or total NOD islets to detect Gag gene expression.

3.3. In vitro Cultured NOD but Not B6-derived Islet MSCs Can Release Gag-containing Microvesicles.

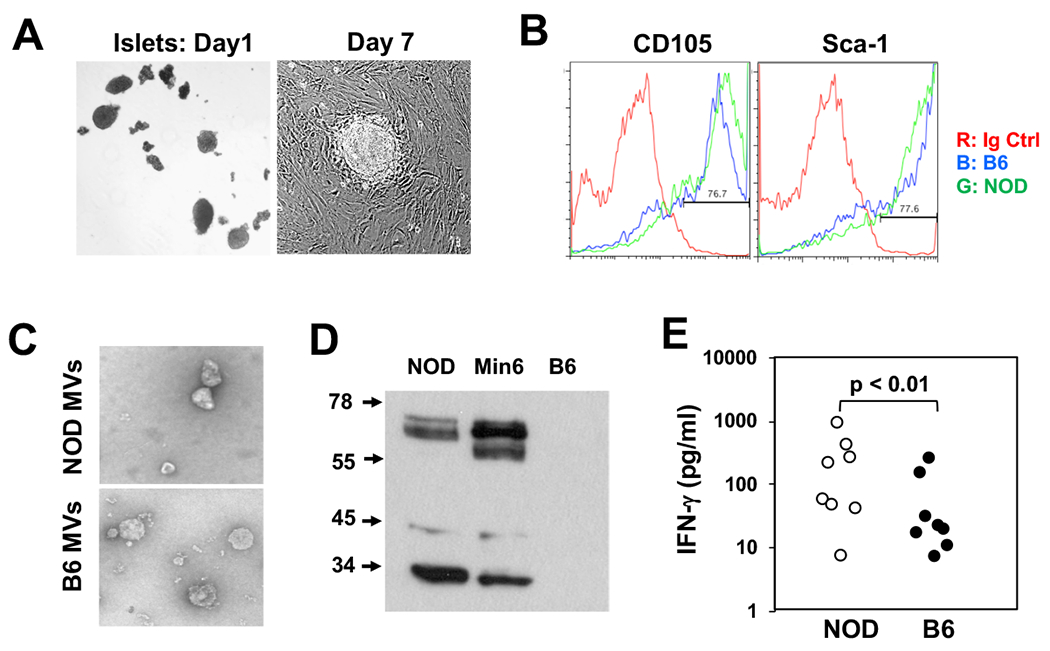

To study immune responses to the ERV antigens, we harvested microvesicles or exosomes from cultured NOD islet-derived MSCs using an established protocol (32). Briefly, hand-picked single islets were cultured in high-glucose DMEM media to allow the growth and expansion of islet MSCs (Fig. 3A). Islets from B6 mice were cultured similarly as controls. Both NOD and B6 islet primary cells expressed the MSC markers, CD105 and Sca-1 (Fig. 3B). The microvesicles from both strains of mice appeared to be similar by shape and size when examined by electron microscopy (Fig. 3C). However, NOD MSCs, but not B6 MSCs, expressed the retroviral antigens. As shown in Fig. 3D, full-length Gag protein and partially degraded Gag fractions or subunits were detected in the NOD, but not B6, microvesicles. A mouse insulinoma cell line Min6, known to release microvesicles containing ERV Env and Gag antigens (31), was used as a positive control. The microvesicles from the cultured NOD or B6 islet MSCs were subsequently tested in vitro for their ability to activate autoreactive cells from NOD mice. We found that the NOD-derived microvesicles were more effective than the B6-derived microvesicles in inducing IFN-γ release when cultured with total NOD splenocytes (Fig. 3E); however, IFN-γ was not detected when B6 splenocytes were used as responders to either NOD- or B6-derived microvesicles. Since both microvesicles cannot directly stimulate purified T cells from NOD spleens, the data suggest that the NOD-derived microvesicles may contain unique antigens that can specifically stimulate the autoreactive T cells present in NOD but not B6 spleens to release IFN-γ after processing and presentation by APCs.

FIG. 3.

Gag-containing microvesicles can be released by cultured islet MSCs. A: Pancreatic islets were cultured without disturbing the flasks to allow the cells to attach and proliferate. Colonies of islet MSCs become visible after one week in culture. When confluent, the MSCs were passaged after releasing the cells with trypsin/EDTA. One third of the cells was re-inoculated for further culture. B: Cultured islet MSCs derived from NOD (Green) or B6 (Blue) islets were stained using antibodies shown. C: Microvesicles (MVs) in the culture supernatants were collected by ultracentrifugation and visualized for electron microscopy. D: Western blot analysis of the MVs (10 μg of total protein per lane) from NOD or B6-derived MSCs or from Min6 insulinoma cells was performed using R187 anti-Gag mAb. E: NOD splenocytes (8-10 week-old females) were stimulated with the MVs (5 μg/ml) from the NOD or B6-derived MSCs. After 72 hours, IFN-γ concentrations in the culture supernatants were measured using a CBA assay kit. Each dot represents one mouse and the data include two separate experiments with similar trend.

3.4. Identification of ERV Gag Gene Variants Expressed in NOD Islets

To identify the Gag genes expressed in the NOD islets, we designed primers for cloning and sequencing the full-length genes. Islets from prediabetic female NOD mice (8-10 wk-old) were used for the cloning. A total 26 full-length Gag genes were cloned and sequenced. Surprisingly, none of 26 clones were identical to each other although they all share above 95% homology (Supplementary Table S1). By searching the genome, one ERV located in chromosome 4 at position from 108152234 to 108153844 (CS4.108x) was identified as a reference gene that has the highest homology to these 26 clones. The complete protein sequence of this reference Gag gene is shown in Fig. 4A. It should be noted that the CS4.108x sequence is not the only ERV sequence that matched the 26 NOD Gag clones. As many as 46 ERVs in the genome, with full-length Gag ORFs, showed above 80% identity to these clones (Supplementary Fig. S1). Therefore, whether the different Gag genes isolated from NOD islets are derived from a single ancestral gene such as CS4.108x, or from a group of similar ERVs is unknown. Among the 26 clones from the NOD islets, 18 clones encoded ORFs of a full-length Gag protein, and 8 clones were non-ORFs due to presence of early stop codons in the genes. We therefore translated the 18 ORFs into proteins and performed homologous analysis, which yielded total 16 distinct Gag proteins as aligned in Fig. 4B (only residues that are different from the reference protein CS4.108x are shown). This alignment analysis allows identification of the hotspots with the Gag genes that are highly variable, which appeared more often for the amino acid residues R, K, S, E, Q, G, V and L.

FIG. 4.

Sequence identity and analysis of ERV Gag genes expressed in the islets of NOD mice. (A) The full protein sequence of a reference Gag gene located at position 108152234 to 108153844 in chromosome 4 (CS4.108x). B: Total RNA was purified from the islets of female 8-week-old NOD mice (n=4) (genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment) and used for cloning full-length Gag genes. Individual clones were sequenced, and the DNA sequences were analyzed. Out of 26 Gag genes cloned from the islets, 16 distinct full-length Gag genes with complete ORFs were identified and their protein sequences were aligned. Only the amino acid residues that show difference from the reference gene (CS4) are shown.

3.5. Activation of Autoreactive T Cells by Gag Proteins

To examine whether Gag could stimulate autoreactive T cells, we compared NOD and B6 splenocytes for their IFN-γ release after culture with a recombinant Gag protein (rGag), which was produced using the Gag gene cloned from Min6 insulinoma. The rGag markedly increased IFN-γ production when cultured with NOD but not with B6 splenocytes (Fig. 5A). In addition, we also produced VLPs that express the Gag protein in a membrane-enclosed form to facilitate antigen processing/presentation. The VLPs were more efficient (> 4-fold) than the rGag in inducing IFN-γ response by the NOD splenocytes (Fig. 5B). Although B6 splenocytes were also activated by the VLPs, the ratio of IFN-γ/IL-10 induced by the VLPs was significantly lower than NOD splenocytes (Fig. 5C). To examine whether the different Gag clones vary in stimulating autoreactive T cells, we compared two different Gag variants, the Gag gene cloned from Min6 insulinoma (Min6.Gag) and an islet-expressing Gag variant, clone NOD.194. The Min6.Gag gene is not expressed in the islets and has a low homology (81.4%) to the reference CS4.108x gene, in contrast to 99.8% for the NOD.194. We observed that the NOD.194 rGag was consistently exhibited stronger activity than the Min6.Gag protein in inducing IFN-γ response by NOD splenocytes (Fig. 5D). In contrast, both rGag proteins were unable to activate B6 splenocytes, suggesting an antigen-specific IFN-γ response by the autoreactive T cells. The enhanced response to the NOD. 194 Gag was also observed when the protein was expressed in VLPs, as demonstrated by the increased ratio of IFN-γ/IL-10 (Fig. 5E).

FIG 5.

Gag proteins can stimulate autoreactive T cells to release IFN-γ. A: Splenocytes of 8-wk-old NOD females (n = 4) or matched B6 mice (n = 3) mice were cultured with recombinant Gag protein (rGag) (5 μg/ml) in vitro. After 48hr, IFN-γ in the culture supernatants was measured in a CBA cytokine assay. Data represent one of two repeated experiments with similar observation. B: NOD or B6 splenocytes (3 mice per group) were cultured with 5 μg/ml of rGag or VLPs for 48hr, cytokines in the supernatants were measured by CBA, and IFN-γ is shown. C: The ratios of IFN-γ/IL-10 in (B) are shown. D: NOD (open circle) or B6 (closed circle) splenocytes were stimulated with two different rGag proteins, Min6.Gag and NOD. 194 (5 μg/ml) or medium control for IFN-γ response. Each dot represents a single mouse and the data were pooled from 3 experiments. E: NOD splenocytes were cultured with VLPs (2 μg/ml) expressing the Min6.Gag and NOD. 194 Gag. Both IFN-γ and IL-10 in the 48hr-supematants were measured and the ratio of IFN-γ/IL-10 was calculated. Paired T-test was used to calculate p values (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; n.s.: not significant).

3.6. Activation of Autoreactive T Cells by Gag Peptides

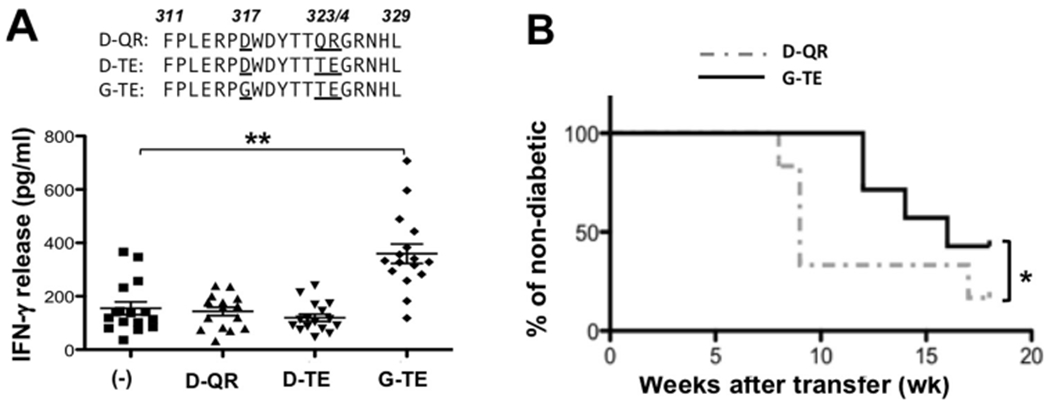

After screening over 50 different Gag peptides, we found one peptide region p311-329 that frequently showed activity in stimulating NOD splenocytes to release IFN-γ, however the response was weak (<300 pg/ml), as compared to the response to rGag (3442 pg/ml). Interestingly, the Gag variants expressed in the islets of NOD mice contain different amino acid sequences at this peptide region. Based on the differences among the islet-expressing variants and the Min6.Gag protein, we selected 3 altered peptide ligands, FPLERPDWDYTTQRGRNHL (D-QR), FPLERPDWDYTTTEGRNHL (D-TE) and FPLERPGWDYTTTEGRNHL (G-TE), to test their ability to stimulate autoreactive T cells. Upon testing on total NOD splenocytes, the third peptide G-TE was identified as the most effective variant to induce IFN-γ release, although the range was high, from 100 to 800 pg/ml, between individual animals (Fig. 6A). We then compared two variant peptides, D-QR and G-TE, for their efficacies inducing tolerance in neonates. Female neonates were injected 4 times over a period of 10 days after birth. At the age of 8 weeks, splenocytes from the treated mice were transferred into NOD.scid recipients to assess the presence of autoreactive T cells. We observed a significant difference between the G-TE vs. D-QR-treated groups, in that the neonatal-treatment with the G-TE peptide was more effective in inducing tolerance than the D-QR peptide, as demonstrated with a delay in diabetes development in the recipients (Fig. 6B). In addition, none of the Gag peptides and the variant peptides, including two hybrid insulin peptides (37) that we created by linking an insulin C-peptide fragment (LQTLAL) with part of the Gag p314-326 peptide (WDYTTTE), were able to stimulate a diabetogenic T-cell clone BDC-2.5 to release IFN-γ (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Identification of a dominant T-cell epitope within Gag protein. A: NOD splenocytes were cultured with 10 μg/ml of 3 altered peptides of p311-329: D-QR, D-TE and G-TE. IFN-γ in the supernatants (48hr) was measured with the CBA assay. Each dot represents a single mouse. Data were combined from 4 separate experiments (T-test was performed, **: p < 0.01). B: NOD neonates were injected with the D-QR (dash line) or G-TE (solid line) peptides for 4 times (5 μg, 5 μg, 10 μg and 10 μg per mouse) over a period of 10 days after birth. At the age of 8 weeks, splenocytes from the treated females were collected and transferred into female NOD.scid (TE recipients: n = 7, QR recipients: n = 6). T1D in the recipients was monitored (Survival analysis was performed using Log-rank test, *: p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The strongest genetic contribution to T1D is that of the class II MHC gene, and it is believed that one or a small group of unique antigens that are preferentially presented by the MHC may be responsible for the activation of autoreactive T cells (38,39), which are the key players driving the development of diabetes. It is puzzling that among a long list of identified candidate autoantigens associated with T1D, none of them can be classified as a primary target of the T cells either because they are not indispensable for the disease development or because they were ineffective in preventing the disease using tolerance protocols. One possibility is that there might be novel antigens remaining to be discovered. In an attempt to identify new antigens, we previously examined microvesicles harvested from insulinoma cells or from cultured islet MSCs and surprisingly, we found that those microvesicles were enriched with ERV antigens (36). Subsequently, we observed that one of the retroviral antigens, Gag, was essential for inducing the T cells to release IFN-γ (31). The current study intended to further study the expression and sequence variations of the Gag in the islets and antigen specificity of the T-cell response.

The expression and distribution of the Gag protein in the pancreas was generally observed in a relatively small proportion of cells within the islets of NOD mice, but absent in the islets of B6 and other diabetes resistant mice. The staining was generally stronger at the periphery of the islets, especially those that were close to blood vessels. The Gag positive cells could be further characterized as non-hematopoietic by their lack of positivity for CD45. Some, but not all, CD 105 positive cells were Gag positive possibly indicating that they were not necessarily endothelial cells by lineage. However, the Sca-1 positivity of the Gag positive cells indicates that they were of a stem cell-like lineage. Since the positive staining is restricted to few cells within the islets, it is unlikely that there is an active retroviral infection. Importantly, NOD mice contain multiple Gag gene variants with complete ORFs. Considering that none of the 26 Gag DNA sequences are 100% identical, the number of Gag variants in NOD islets could be much higher than that in the genome, it is very possible that these variants may have derived from one or a group of similar ancestor Gag genes through hyper variable mutations at mutational hotspots, which might be a result of retrovirus transcriptase activity or caused by other retroviral or host-dense mechanisms. Alternatively, a different endogenous retrovirus may be activated in the NOD mice, which may facilitate the mobilization of other similar endogenous retroviral transcripts such as the NOD Gag genes through pseudotyping (40). The pseudotyped transcripts, even if they are defective, could be transferred and integrated into new cells and be inappropriately expressed.

In contrast to NOD, a significantly smaller proportion of the Gag clones in the diabetes-resistant mice were ORF genes, suggesting that there may be a mechanism suppressing the production of ORFs in these mice. In fact, after being placed in culture for more than 10 passages, the B6-derived MSCs that were originally negative for Gag started to show positivity for Gag protein and produced MV expressing Gag (Fig. S2), indicating that perhaps an epigenetically silent Gag in the B6 cells becomes activated perhaps in long term culture. Whether a dominant suppression of Gag gene expression in the F1 progenies of NOD and B6 mice is similarly controlled by the few non-MHC genes that were suggested previously to control insulitis/diabetes resistance (41) remains to be determined. Another interesting observation was that male NOD mice also express Gag genes with ORFs in the islets, however, most of these Gag genes matched ERV sequences located in the Y chromosome, which have much lesser homology than the CS4.108x reference gene to the Gag variants expressed in female NOD islets, suggesting a possible regulatory/inhibitory role of these male-specific Gag antigens. Regardless of what roles individual Gag gene variants may play during the course of islet autoimmunity, the fact that NOD mouse islets expressed a high number of variant genes in correct ORFs is indeed a dangerous signal to the immune system, particularly to T cells. Assuming that these Gag variants are all expressed, it would be tempting to speculate that the overall burden of the expression may eventually trigger T-cell-mediated immune response against the variable regions within the molecule, regardless of whether the system is exposed previously to the molecule during development.

The task of discovering dominant epitopes within the Gag protein through the use of a limited number of synthetic peptides revealed one peptide region p311-329 caused weak but distinct activation of IFN-γ secretion by the autoreactive T cells. It cannot be excluded that this weak peptide response to the peptide could be due to antigen presentation that is different after processing whole protein since the rGag proteins indeed strongly induced IFN-γ response. Nevertheless, one altered peptide ligand was found more effective than the other two altered peptides of the same region, indicating that mutations within the Gag variants could affect the T-cell response to Gag. This argument is supported by the evidence that all the Gag variants expressed in the islets of NOD female mice contain the TE motif at positions 323/324, which is the correct motif required for the IFN-γ response. In contrast, the Gag variants and their peptides that contain a QR motif at the same positions was not effective and interestingly, such variants were also not found in the islets of the female mice. Whether this lack of reactivity to the QR motif is due to a weaker binding to the I-Ag7 class II MHC molecule (42) remains to be tested. Coincidentally, the p311-329 region was previously shown to be a key determinant for distinguishing between N-tropic (QR) vs. B-tropic (TE) MuLV viruses (43), which determines whether the virus could infect NIH Swiss (H-2q) or BALB/c (H-2d) mice, respectively (44). It would be interesting to examine whether this strain-specific tropism is attributed to the T-cell response to this peptide region.

In summary, we observed a surprising retroviral event in the NOD islets in which a large number of ERV Gag variants with complete ORFs are expressed; whereas, in diabetes-resistant mice, non-ORFs of Gag variants are present in islets, incapable of producing Gag protein. The study also provided new evidence to confirm that autoreactive T cells can react to the Gag protein. Likely, it is the altered peptide ligands within the Gag variants expressed in the islets of NOD female mice that could preferentially induce effector T cells to release IFN-γ.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Endogenous retrovirus (ERV) is associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D).

ERV antigen Gag is expressed in islet mesenchymal stem cells.

The islet Gag antigen is encoded by many mutated Gag genes.

The mutated Gag antigen contains altered peptide ligands to stimulate autoreactive T cells.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yang D. Dai is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We thank Dr. Ta-Hsiang Chao at Estel Biosciences (San Diego) for the purification of recombinant Gag protein.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to Y.D.D. from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)(R01DK091663 and R21AI139564) and, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID, Rocky Mountain Laboratories in the United States.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

REFERENCE

- 1.Eisenbarth GS (2010) Banting Lecture 2009: An unfinished journey: molecular pathogenesis to prevention of type 1A diabetes. Diabetes 59, 759–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarukhan A, Gombert JM, Olivi M, Bach JF, Carnaud C, and Garchon HJ (1994) Anchored polymerase chain reaction based analysis of the V beta repertoire in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Eur J Immunol 24, 1750–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker FJ, Lee M, Chien YH, and Davis MM (2002) Restricted islet-cell reactive T cell repertoire of early pancreatic islet infiltrates in NOD mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 9374–9379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasinski JM, Yu L, Nakayama M, Li MM, Lipes MA, Eisenbarth GS, and Liu E (2006) Transgenic insulin (B:9-23) T-cell receptor mice develop autoimmune diabetes dependent upon RAG genotype, H-2g7 homozygosity, and insulin 2 gene knockout. Diabetes 55, 1978–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kent SC, Chen Y, Bregoli L, Clemmings SM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, and Hafler DA (2005) Expanded T cells from pancreatic lymph nodes of type 1 diabetic subjects recognize an insulin epitope. Nature 435, 224–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zekzer D, Wong FS, Wen L, Altieri M, Gurlo T, von Grafenstein H, and Sherwin RS (1997) Inhibition of diabetes by an insulin-reactive CD4 T-cell clone in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Diabetes 46, 1124–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton AR, Vincent E, Arnold PY, Lennon GP, Smeltzer M, Li CS, Haskins K, Hutton J, Tisch RM, Sercarz EE, Santamaria P, Workman CJ, and Vignali DA (2008) On the pathogenicity of autoantigen-specific T-cell receptors. Diabetes 57, 1321–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai YD, Jensen KP, Marrero I, Li N, Quinn A, and Sercarz EE (2008) N-terminal flanking residues of a diabetes-associated GAD65 determinant are necessary for activation of antigen-specific T cells in diabetes-resistant mice. Eur J Immunol 38, 968–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suri A, Vidavsky I, van der Drift K, Kanagawa O, Gross ML, and Unanue ER (2002) In APCs, the autologous peptides selected by the diabetogenic I-Ag7 molecule are unique and determined by the amino acid changes in the P9 pocket. J Immunol 168, 1235–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoglund P, Mintern J, Waltzinger C, Heath W, Benoist C, and Mathis D (1999) Initiation of autoimmune diabetes by developmentally regulated presentation of islet cell antigens in the pancreatic lymph nodes. J Exp Med 189, 331–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trudeau JD, Dutz JP, Arany E, Hill DJ, Fieldus WE, and Finegood DT (2000) Neonatal beta-cell apoptosis: a trigger for autoimmune diabetes? Diabetes 49, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diana J, Simoni Y, Furio L, Beaudoin L, Agerberth B, Barrat F, and Lehuen A (2013) Crosstalk between neutrophils, B-1a cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells initiates autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med 19, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA, Gordon JI, and Chervonsky AV (2008) Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature 455, 1109–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Xu B, Michie SA, Rubins KH, Schreriber RD, and McDevitt HO (2008) Interferon-alpha initiates type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 12439–12444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng M, Hu Z, Shi X, Li X, Zhan X, Li XD, Wang J, Choi JH, Wang KW, Purrington T, Tang M, Fina M, DeBerardinis RJ, Moresco EM, Pedersen G, McInerney GM, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Chen ZJ, and Beutler B (2014) MAVS, cGAS, and endogenous retroviruses in T-independent B cell responses. Science 346, 1486–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Treger RS, Pope SD, Kong Y, Tokuyama M, Taura M, and Iwasaki A (2019) The Lupus Susceptibility Locus Sgp3 Encodes the Suppressor of Endogenous Retrovirus Expression SNERV. Immunity 50, 334–347 e339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stocking C, and Kozak CA (2008) Murine endogenous retroviruses. Cell Mol Life Sci 65, 3383–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu P (2016) The potential role of retroviruses in autoimmunity. Immunol Rev 269, 85–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perron H, Garson JA, Bedin F, Beseme F, Paranhos-Baccala G, Komurian-Pradel F, Mallet F, Tuke PW, Voisset C, Blond JL, Lalande B, Seigneurin JM, and Mandrand B (1997) Molecular identification of a novel retrovirus repeatedly isolated from patients with multiple sclerosis. The Collaborative Research Group on Multiple Sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 7583–7588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanchong CA, Zhou B, Rupert KL, Chung EK, Jones KN, Sotos JF, Zipf WB, Rennebohm RM, and Yung Yu C (2000) Deficiencies of human complement component C4A and C4B and heterozygosity in length variants of RP-C4-CYP21-TNX (RCCX) modules in caucasians. The load of RCCX genetic diversity on major histocompatibility complex-associated disease. J Exp Med 191, 2183–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herve CA, Lugli EB, Brand A, Griffiths DJ, and Venables PJ (2002) Autoantibodies to human endogenous retrovirus-K are frequently detected in health and disease and react with multiple epitopes. Clin Exp Immunol 128, 75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad B, Weissmahr RN, Boni J, Arcari R, Schupbach J, and Mach B (1997) A human endogenous retroviral superantigen as candidate autoimmune gene in type I diabetes. Cell 90, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lower R, Tonjes RR, Boller K, Denner J, Kaiser B, Phelps RC, Lower J, Kurth R, Badenhoop K, Donner H, Usadel KH, Miethke T, Lapatschek M, and Wagner H (1998) Development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus does not depend on specific expression of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K. Cell 95, 11–14; discussion 16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason MJ, Speake C, Gersuk VH, Nguyen QA, O’Brien KK, Odegard JM, Buckner JH, Greenbaum CJ, Chaussabel D, and Nepom GT (2014) Low HERV-K(C4) copy number is associated with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 63, 1789–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levet S, Medina J, Joanou J, Demolder A, Queruel N, Reant K, Normand M, Seffals M, Dimier J, Germi R, Piofczyk T, Portoukalian J, Touraine JL, and Perron H (2017) An ancestral retroviral protein identified as a therapeutic target in type-1 diabetes. JCI insight 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niegowska M, Wajda-Cuszlag M, Stepien-Ptak G, Trojanek J, Michalkiewicz J, Szalecki M, and Sechi LA (2019) Anti-HERV-WEnv antibodies are correlated with seroreactivity against Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in children and youths at T1D risk. Scientific reports 9, 6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaskins HR, Prochazka M, Hamaguchi K, Serreze DV, and Leiter EH (1992) Beta cell expression of endogenous xenotropic retrovirus distinguishes diabetes-susceptible NOD/Lt from resistant NON/Lt mice. J Clin Invest 90, 2220–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsumura H, Miyazawa M, Ogawa S, Wang JZ, Ito Y, and Shimura K (1998) Detection of endogenous retrovirus antigens in NOD mouse pancreatic beta-cells. Laboratory animals 32, 86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levisetti MG, Suri A, Vidavsky I, Gross ML, Kanagawa O, and Unanue ER (2003) Autoantibodies and CD4 T cells target a beta cell retroviral envelope protein in non-obese diabetic mice. Int Immunol 15, 1473–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triviai I, Ziegler M, Bergholz U, Oler AJ, Stubig T, Prassolov V, Fehse B, Kozak CA, Kroger N, and Stocking C (2014) Endogenous retrovirus induces leukemia in a xenograft mouse model for primary myelofibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 8595–8600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bashratyan R, Regn D, Rahman MJ, Marquardt K, Fink E, Hu WY, Elder JH, Binley J, Sherman LA, and Dai YD (2017) Type 1 diabetes pathogenesis is modulated by spontaneous autoimmune responses to endogenous retrovirus antigens in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol 47, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman MJ, Regn D, Bashratyan R, and Dai YD (2014) Exosomes Released by Islet-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Trigger Autoimmune Responses in NOD Mice. Diabetes 63, 1008–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chesebro B, Britt W, Evans L, Wehrly K, Nishio J, and Cloyd M (1983) Characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive with murine leukemia viruses: use in analysis of strains of friend MCF and Friend ecotropic murine leukemia virus. Virology 127, 134–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiter EH (2001) The NOD mouse: a model for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. in Curr Protoc Immunol. pp Unit 15.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong T, Crooks ET, Osawa K, and Binley JM (2012) HIV-1 virus-like particles bearing pure env trimers expose neutralizing epitopes but occlude nonneutralizing epitopes. Journal of virology 86, 3574–3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheng H, Hassanali S, Nugent C, Wen L, Hamilton-Williams E, Dias P, and Dai YD (2011) Insulinoma-released exosomes or microparticles are immunostimulatory and can activate autoreactive T cells spontaneously developed in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol 187, 1591–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delong T, Wiles TA, Baker RL, Bradley B, Barbour G, Reisdorph R, Armstrong M, Powell RL, Reisdorph N, Kumar N, Elso CM, DeNicola M, Bottino R, Powers AC, Harlan DM, Kent SC, Mannering SI, and Haskins K (2016) Pathogenic CD4 T cells in type 1 diabetes recognize epitopes formed by peptide fusion. Science 351, 711–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDevitt H, Singer S, and Tisch R (1996) The role of MHC class II genes in susceptibility and resistance to type I diabetes mellitus in the NOD mouse. Horm Metab Res 28, 287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sercarz EE (2000) Driver clones and determinant spreading. J Autoimmun 14, 275–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans LH, Alamgir AS, Owens N, Weber N, Virtaneva K, Barbian K, Babar A, Malik F, and Rosenke K (2009) Mobilization of endogenous retroviruses in mice after infection with an exogenous retrovirus. Journal of virology 83, 2429–2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wicker LS, Miller BJ, Coker LZ, McNally SE, Scott S, Mullen Y, and Appel MC (1987) Genetic control of diabetes and insulitis in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse. J Exp Med 165, 1639–1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corper AL, Stratmann T, Apostolopoulos V, Scott CA, Garcia KC, Kang AS, Wilson IA, and Teyton L (2000) A structural framework for deciphering the link between I-Ag7 and autoimmune diabetes. Science 288, 505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ou CY, Boone LR, Koh CK, Tennant RW, and Yang WK (1983) Nucleotide sequences of gag-pol regions that determine the Fv-1 host range property of BALB/c N-tropic and B-tropic murine leukemia viruses. Journal of virology 48, 779–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartley JW, Rowe WP, and Huebner RJ (1970) Host-range restrictions of murine leukemia viruses in mouse embryo cell cultures. Journal of virology 5, 221–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.