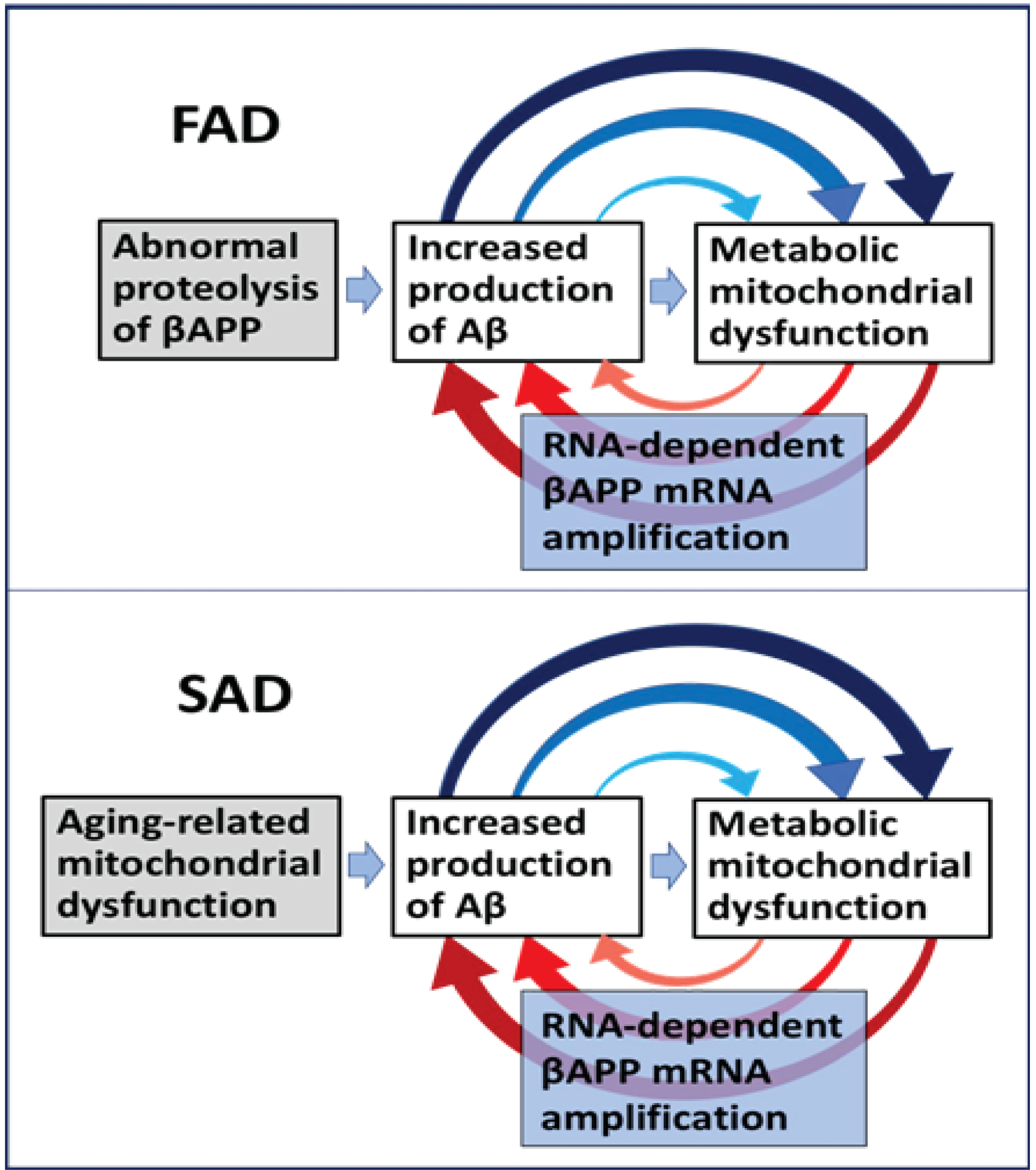

Figure 4: The engine that drives AD: Self-propagating mutual feedback cycles of mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated overproduction of beta-amyloid and vice versa in Alzheimer’s disease.

FAD: Familial Alzheimer’s disease; SAD: Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease; Highlighted in grey: Initial stimuli of the increased production of Aβ (different in FAD and SAD); Highlighted in blue: asymmetric RNA-dependent βAPP mRNA amplification, a molecular basis of beta-amyloid overproduction in Alzheimer’s disease (note a requirement for βAPP TSS utilization discussed in main text above); Horizontal arrows: the initial Aβ overproduction cycle; Arched arrows: Mutual feedback cycles; Blue arrows: Aβ-mediated induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and, possibly, ER stress; Red arrows: Mitochondrial dysfunction (and, possibly, ER stress)-mediated asymmetric RNA-dependent amplification of βAPP mRNA resulting in overproduction of Aβ. Note that in FAD, mitochondrial dysfunction is an intrinsic component of the amyloid cascade whereas in SAD, the initial mitochondrial pathology hierarchically supersedes and triggers Aβ pathology, where self-perpetuating mutual Aβ overproduction/mitochondrial dysfunction feedback cycles are, as in FAD, a central component of the amyloid cascade. In FAD, the initial increased production of Aβ results from mutations-driven abnormal proteolysis of βAPP and occurs relatively early in life, whereas in SAD, it is compelled by an aging-dependent component; hence drastic temporal difference in the age of onset yet profound pathological and symptomatic similarity in the progression of familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting mechanistically identical nature of feedback cycles in both forms of AD.