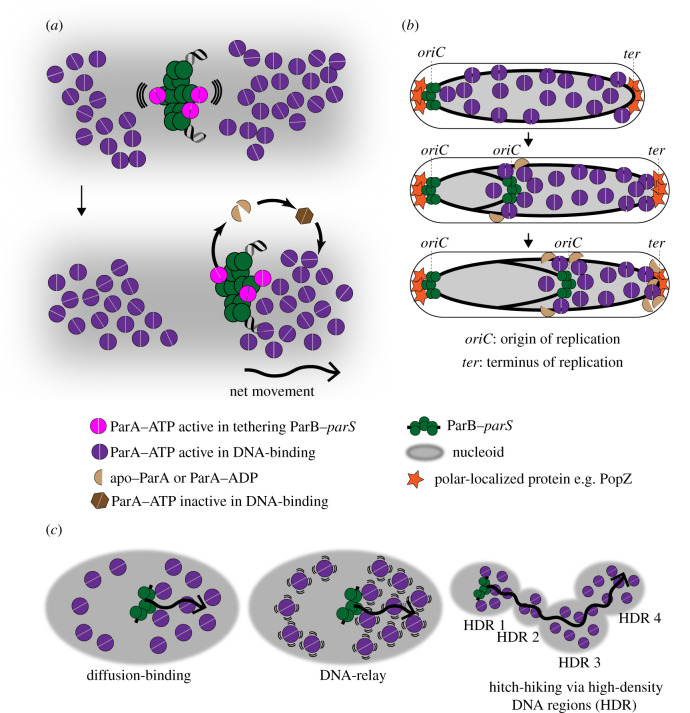

Figure 2.

ParA drives the movement of ParB-bound DNA to segregate plasmids and chromosomes. (a) A diffusion-ratchet model for ParA-mediated transport of ParB-bound DNA. A ParB–DNA complex (green) interacts with ParA–ATP (violet) to tether to the nucleoid (grey), and to stimulate the ATPase activity of ParA. ParA–ATP dimers (violet) bind the nucleoid non-specifically. After ATP hydrolysis, monomers of apo–ParA/ParA–ADP (light brown) no longer bind DNA, thus creating a zone of depletion of ParA–ATP surrounding the ParB–DNA complex. By thermal fluctuation (wavy lines), the ParB–DNA complex moves to the edge of the zone of depletion to rebind ParA–ATP. The initial movement of the ParB–DNA complex in one chosen direction enforces the continued movement in the same direction, resulting in a long-range directional movement of the DNA (see b). The released apo–ParA/ParA–ADP (light brown) rebinds ATP but cannot immediately bind DNA (the dark brown hexagon) until a transition occurs in the ParA–ATP structure. (b) The segregation of the origin-proximal region of the chromosome by the ParABS system. For example, in C. crescentus, one ParB–DNA complex remains at the pole after chromosome replication, while the other moves along the gradient of ParA–ATP, via the diffusion-ratchet mechanism, to the opposite cell pole. The polarly localized proteins (e.g. PopZ, orange) contribute to maintaining the ParA–ATP gradient by sequestering apo–ParA/ParA–ADP away from the nucleoid and to regenerate them at the pole. (c) Other variations of the diffusion-ratchet model have been proposed to include an element of DNA elasticity (i.e. the DNA-relay model) or high-density DNA regions (HDR) (i.e. the hitch-hiking model). A wavy arrow indicates the directional movement of the partition complex.