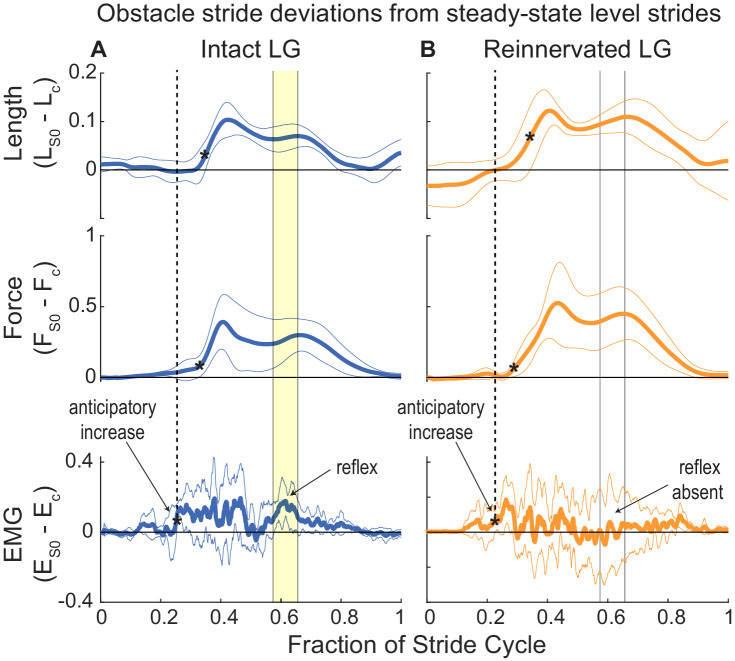

Figure 7. Deviations from steady state in the stride cycle trajectories of muscle length, force and activation, between obstacle strides (S 0) and level strides (grand mean ±95% ci across individuals).

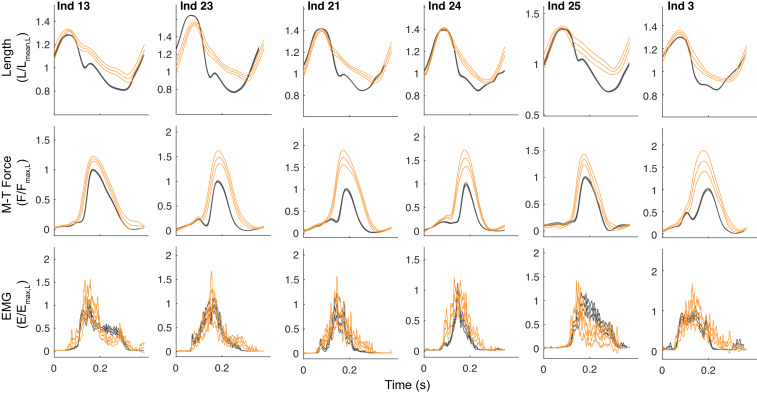

The horizontal zero line indicates no difference from steady state in S 0. The stride cycle is from mid-swing to mid-swing, as in Figure 2. A black asterisk (*) indicates the first timepoint in each trajectory that differs significantly from the level mean. The dashed vertical line and arrow indicating ‘anticipatory increase’ highlights a significant increase in EMG that starts before deviations length and force in S 0. In (A) (iLG), solid vertical lines and yellow fill indicates a 2nd period of significantly increased EMG in late stance that correlates with increased fascicle length and force, suggesting a reflex response. In (B) (rLG), the anticipatory increase in EMG is present; however, wide confidence intervals for EMG in late stance indicates inconsistent patterns of activity across individuals, despite similar increases in length and force as iLG. This suggests disrupted autogenic feedback and idiosyncratic heterogenic feedback patterns across individuals (Figure 7—figure supplement 1).