Abstract

The ecosystem carbon (C) balance in permafrost regions, which has a global significance in understanding the terrestrial C-climate feedback, is significantly regulated by nitrogen (N) dynamics. However, our knowledge on temporal changes in vegetation N limitation (i.e., the supply of N relative to plant N demand) in permafrost ecosystems is still limited. Based on the combination of isotopic observations derived from a re-sampling campaign along a ~3000 km transect and simulations obtained from a process-based biogeochemical model, here we detect changes in ecosystem N cycle across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region over the past decade. We find that vegetation N limitation becomes stronger despite the increased available N production. The enhanced N limitation on vegetation growth is driven by the joint effects of elevated plant N demand and gaseous N loss. These findings suggest that N would constrain the future trajectory of ecosystem C cycle in this alpine permafrost region.

Subject terms: Element cycles, Element cycles

Massive stores of carbon and nutrients in permafrost could be released by global warming. Here the authors show that though warming across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region accelerates nitrogen liberation, contrary to expectations the elevated nutrients do not alleviate plant nitrogen limitation.

Introduction

Permafrost regions store more than 1300 Pg (1 Pg = 1015 g) carbon (C, ca. 43% of the global soil organic C storage) in ~15% of the global land area1,2. During the past decades, permafrost regions have experienced two times faster climate warming compared with the rest of Earth’s areas3,4, which has triggered extensive permafrost thaw1,4. Consequently, large amounts of C stored in permafrost regions may be emitted into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) because of the accelerated microbial decomposition5–7, potentially aggravating global warming through the positive C-climate feedback4. However, permafrost regions may still appear as a C sink due to the enhanced vegetation productivity under both the current and near-future climate scenarios8,9. These uncertainties in ecosystem C balance across permafrost regions could be partly ascribed to ecosystem nitrogen (N) dynamics, especially changes in the status of N limitation on vegetation under changing environment8–10. Vegetation N limitation is characterized as the lower supply of N to plants relative to their N demand and jointly determined by the provision of available N and plant N requirement11–13. In general, the greater the vegetation N limitation is, the less C vegetation would sequester and the more likely permafrost ecosystems function as a C source; on the contrary, permafrost ecosystems would tend to act as a C sink8,14. Consistent with this conceptual understanding, ecosystem C stock simulated with a C–N model configuration could be ~35 Pg lower than that simulated with a C-only configuration across the circumpolar permafrost region in 23008. Therefore, deeper exploration of ecosystem N dynamics in permafrost regions is imperative to better predict permafrost C cycle and its feedback to climate warming.

During the last decade, the global change research community has paid great attention to the site-level dynamics of available N supply to plants in permafrost ecosystems15–20. Based on these efforts, an enhanced supply of plant-available N derived from the accelerated N mineralization or the release of originally frozen available N is observed with climate warming or permafrost thaw15–20. In addition, there are also studies that reveal increased plant productivity17,21 or enhanced plant N pool17 in permafrost ecosystems, reflecting an elevated plant N demand under environmental changes. These studies have advanced our understanding on both the dynamics of available N supply and plant N demand in permafrost regions. However, little is known about the dynamics of N supply relative to plant N demand across permafrost regions, especially over the broad geographic scale. This knowledge gap constrains our understanding on the status of vegetation N limitation and prevents an accurate prediction of the direction and magnitude of permafrost C-climate feedback.

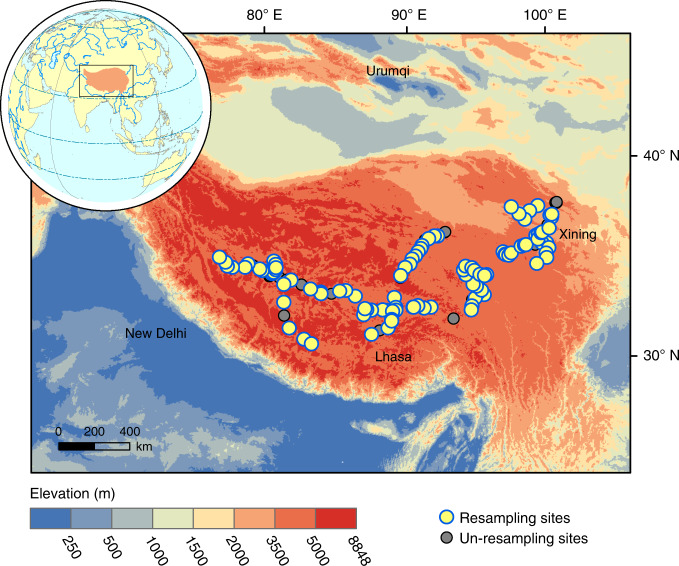

To fill the knowledge gap mentioned above, we conducted a large-scale repeated sampling during the 2000s and the 2010s along a ~3000 km transect on the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), the largest alpine permafrost region around the world22, which has experienced fast warming, elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration (Supplementary Fig. 2) and extensive permafrost thaw as other permafrost regions4,23. The initial field campaign that investigated 135 sites across the study area was carried out during the period 2001~2004, while the revisited field campaign that covered 107 of the original 135 sites was performed during the period of 2013~2014 (Fig. 1). For each paired sampling sites, the investigation methods are identical (see details in “Methods” section). Based on the collected samples during the two sampling campaigns, plant δ15N and bulk soil δ15N (i.e., δ15N of total inorganic and organic N pools in the soil) were measured to characterize changes in ecosystem N cycle in this alpine permafrost region. To further explore ecosystem N dynamics, N cycling processes were simulated for each resampling site with a process-based biogeochemical model—DeNitrification-DeComposition (DNDC)24,25. With all the obtained measurements and simulations, this study aims to examine the temporal changes in ecosystem N cycle, especially vegetation N limitation across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region over the last decade. We find that plant growth becomes more N-limited in this alpine permafrost region despite the enhanced provision of plant-available N.

Fig. 1. Distribution of sampling sites on the Tibetan Plateau.

Yellow and grey circles jointly represent the original 135 sampling sites surveyed during the period of 2001 ~ 2004. Among them, the yellow circles denote the 107 resampling sites investigated during 2013~2014 and the grey circles indicate the unresampling sites due to practical limits such as road rebuilding. The background map represents the elevation across the study area.

Results and discussion

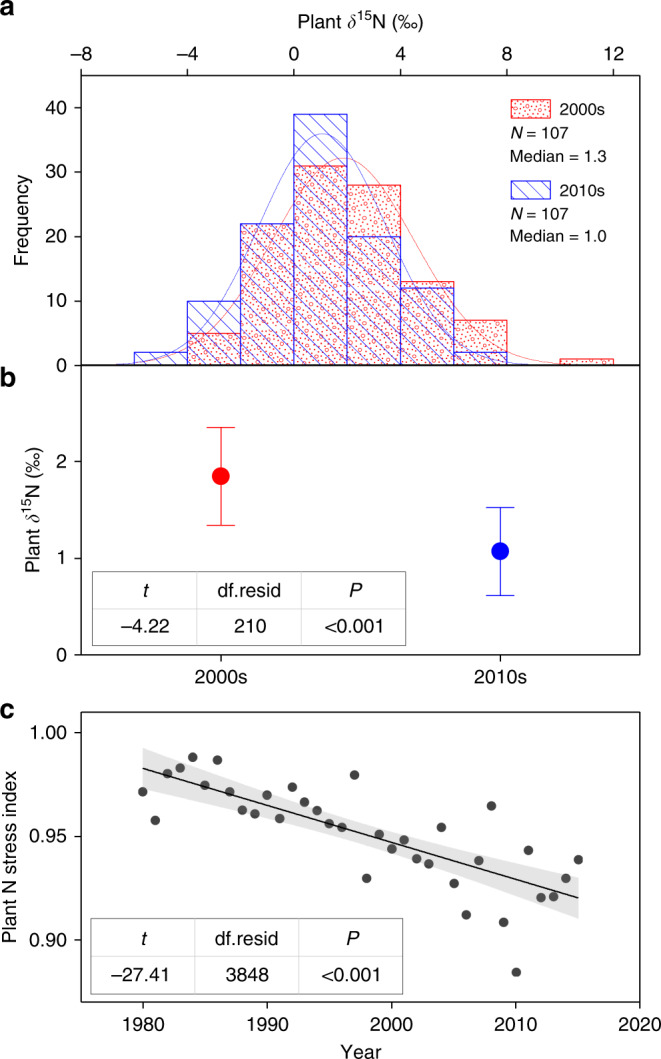

Decreased plant δ15N over time

Over the past decade, neither mean annual precipitation (MAP; Supplementary Fig. 2) nor atmospheric N deposition (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) experienced significant changes, whereas both mean annual air temperature (MAAT) and atmospheric CO2 concentration significantly increased (P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 2) across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Under these environmental changes, plant δ15N across this alpine permafrost region significantly decreased during the period from the 2000s to the 2010s (median in the 2000s: 1.3‰, median in the 2010s: 1.0‰, P < 0.001; Fig. 2a, b). On average, the absolute changing rate in plant δ15N was −0.02‰ per year (within the range of −0.043 ~ −0.016‰ per year globally13) and the relative changing rate was −1.7% per year. Further analyses revealed that plant δ15N tended to decrease among 73 of the total 107 resampling sites and the decline in plant δ15N remained significant until >74 resampling sites were removed from the initial analysis with 107 resampling sites (Supplementary Fig. 4), demonstrating the robustness of isotopic dynamics observed in this study.

Fig. 2. Changes in plant δ15N and N stress index over time.

a–c Frequency distributions of plant δ15N during the two sampling periods, changes in plant δ15N derived from the large-scale resampling investigations and changes in plant N stress index derived from the DeNitrification-DeComposition (DNDC) model, respectively. Plant N stress index refers to the supply of N relative to plant demand, with a lower value meaning a greater limitation of N on plant growth38–40. Temporal dynamics of both indicators were examined with linear mixed-effects models, in which the fixed effect was year and the random effect was sampling site. Points in b denote mean values and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The shade accompanying with the solid fitted line in c represents 95% confidential interval. N, the number of sites used for analyzing plant δ15N; median, median value of plant δ15N; df.resid, residual degrees of freedom.

Changes in plant δ15N could be associated with multiple reasons, such as shifts in vegetation community, atmospheric N deposition, biological N fixation and plant N uptake through root or mycorrhizae26–29. However, both vegetation community (Supplementary Figs. 5–7 and Supplementary Note 1) and atmospheric N deposition (both rate and δ15N; Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) were stabilized over the two sampling periods, and thus had limited effects on the plant δ15N dynamics observed in this study. Moreover, despite biological N fixation increased over the last decade (P < 0.001; Fig. 3), it should not be the main reason for the decrease in plant δ15N, as plant δ15N also significantly decreased among the investigated sites without Leguminosae (P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 8). In addition, plant N uptake through roots could elevate rather than diminish plant δ15N, because bulk soil δ15N increased over the detection period (P < 0.01; Fig. 4) and the fractionation of N isotopes was minimal during root N uptake in natural ecosystems29–31. In contrast to root N uptake, plant N uptake through mycorrhizae can decrease plant δ15N given: (i) the transfer of 15N-deleted N to plants by mycorrhizae13,26,28,29; (ii) the crucial role of mycorrhizae in supplying N to plants under N-limited conditions13,28,31,32; (iii) the widespread distribution of plants associated with mycorrhizae33 across the 107 resampling sites; (iv) the potentially enhanced mycorrhizal colonization (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Note 2) driven by the two major environmental changes on the Tibetan Plateau (CO2 enrichment and climate warming, Supplementary Fig. 2). Nevertheless, besides N limitation, other factors especially phosphorus (P) limitation and water stress could also make plants to invest more to mycorrhizae31,34,35. However, soil N : P ratio in the top 10 cm across the study area significantly decreased over the detection period (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating that N rather than P limitation was more likely to reduce plant δ15N via mycorrhizae. Moreover, topsoil moisture across the study area did not exhibit significant change over the detection period (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12, and Supplementary Note 3), reflecting the minimal effect of water stress on the plant δ15N dynamics. Taken together, of all the factors considered, an enhancement in reliance on mycorrhizae for N acquisition could be the plausible reason for the decreased plant δ15N observed in this study.

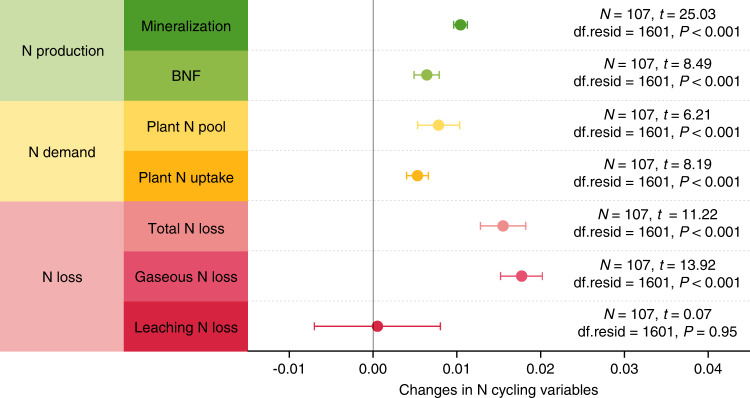

Fig. 3. Temporal dynamics of N production, demand and loss.

Changes in production of available N are reflected by annual soil N mineralization and biological N fixation rates (BNF), changes in plant N demand are represented by plant N pool and annual plant N uptake rate, and changes in ecosystem N loss are indicated by gaseous N loss, leaching N loss and total N loss (sum of gaseous and leaching N losses) over 2000s~2010s. Data of the N cycling variables were derived from the DeNitrification-DeComposition (DNDC) simulations. Changes in N cycling variables were characterized by the slope of relationship between an indicator and the fixed effect (year), which were examined with linear mixed-effects models after data normalization. Points in the plot denote the estimated model slopes and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. N, the number of sites used for analyzing temporal dynamics of each indicator; df.resid, residual degrees of freedom.

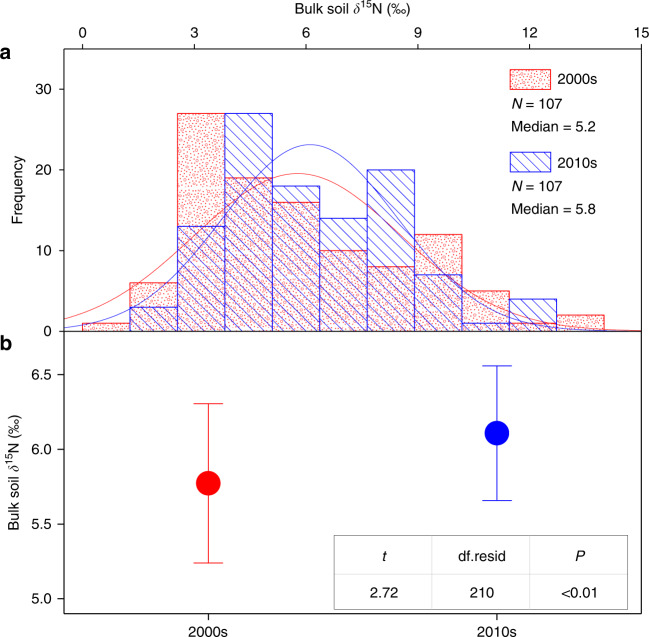

Fig. 4. Changes in topsoil δ15N over 2000s ~ 2010s.

a, b Frequency distributions of bulk soil δ15N and changes in bulk soil δ15N during the period between the 2000s and the 2010s, respectively. The change in bulk soil δ15N was examined with linear mixed-effects model, in which the fixed effect was year and the random effect was sampling site. Points in b denote mean values and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. N, the number of sites used for analyzing bulk soil δ15N; Median, median value of bulk soil δ15N; df.resid, residual degrees of freedom.

As a widely used indicator to reflect the supply of N relative to plant N demand, a lower plant δ15N generally represents an elevated N limitation12,13,26,27,36,37. Due to this point, the decreased plant δ15N observed in this study suggests enhanced vegetation N limitation across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region over the last decade. To further demonstrate this point, we conducted a historical simulation from 1980 to 2015 for the 107 resampling sites with the DNDC model and acquired an indicator (plant N stress index) that represented the supply of N relative to plant demand38–40. The lower the plant N stress value is, the greater the vegetation N limitation is38–40. Our results showed that the plant N stress index significantly decreased during the past decades (P < 0.001; Fig. 2c), confirming the enhancement of vegetation N limitation across the study area. Besides the plant N stress index, we also explored the dynamics of available N production by analyzing changes in the simulated annual rates of soil N mineralization and biological N fixation. In contrast to the plant N stress index, these two processes were significantly accelerated during the period between the 2000s and the 2010s (P < 0.001; Fig. 3), indicating the enhanced production of available N across the study area. Collectively, these results highlighted that vegetation N limitation became stronger across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region during the past decade despite the increased production of available N.

Enhanced plant N demand under changing environment

The enhancement of vegetation N limitation could be associated with increases in plant N demand41. To illustrate this point, we detected the changes in indicators characterizing plant N demand derived from the DNDC simulations, including plant N pool and annual plant N uptake rate. Results showed that both indicators significantly increased during the last decade (P < 0.001; Fig. 3), indicating that increased plant N demand could promote vegetation N limitation across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Based on the factorial analysis conducted through the DNDC model, we further disentangled the effects of environmental changes on plant N pool and annual plant N uptake rate. Our results illustrated that climate warming and CO2 enrichment played dominant roles in elevating these two parameters, highlighting their crucial effects on stimulating plant N demand (Supplementary Fig. 13a–d). Of them, climate warming can enhance vegetation productivity and subsequent plant N demand by accelerating plant metabolic activity and extending growing season length36, while CO2 enrichment can improve plant N demand through its fertilization effect11,42. In support of this interpretation, large amounts of evidences have revealed earlier growing season43,44, larger vegetation productivity43,45 and continuous ecosystem C sink45,46 across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region during the past decades.

Increased ecosystem N loss induced by environmental change

The enhancement of vegetation N limitation could also be linked with processes that tend to decrease the supply of available N to plant growth41. To demonstrate this point, we examined changes in ecosystem N loss (gaseous N loss and leaching N loss) derived from the DNDC simulations. Our results showed that annual total ecosystem N loss rate significantly increased during the period from the 2000s to the 2010s (P < 0.001; Fig. 3) and the enhancement in total ecosystem N loss was largely due to the significant increase in gaseous N loss (P < 0.001; Fig. 3). The increase in gaseous N loss has potentials to reduce the supply of N relative to plant N demand and hence tends to induce the enhanced vegetation N limitation. Based on the factorial analysis conducted in the DNDC model, we found that climate warming was the major driver of the increased gaseous N loss over the past decade (Supplementary Fig. 13e, f). Ecologically, climate warming can promote gaseous N loss through (i) enhancing the production of available N substrates47,48 for nitrification and denitrification by stimulating microbial biomass or activity49,50, (ii) improving the supply of C for nitrifiers and denitrifiers by increasing root exudations24,25 and (iii) accelerating the diffusion of gaseous N generated by nitrification and denitrification processes51. Moreover, CO2 enrichment can also stimulate gaseous N loss (Supplementary Fig. 13e, f), probably due to the enhancement in soil biological activity or labile C availability under elevated CO252. Besides climate warming and CO2 enrichment, soil moisture is known as another key factor regulating ecosystem gaseous N loss47, however, topsoil moisture across the study area experienced no significant change over the detection period (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12, and Supplementary Note 3) and did not exhibit significant association with the simulated gaseous N loss (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Note 3), indicating its limited effect on the increased gaseous N loss across the study area.

Elevated bulk soil δ15N between the sampling interval

The increase in both plant N demand and ecosystem external N loss was confirmed by the increases in bulk soil δ15N observed in this study, which was a comprehensive indicator of ecosystem N cycle29,53,54. To be specific, our results showed that bulk soil δ15N in the top 10 cm across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region significantly increased during the period 2000s~2010s (median in the 2000s: 5.2‰, median in the 2010s: 5.8‰, P < 0.01; Fig. 4). The absolute changing rate of bulk soil δ15N was 0.05‰ per year and the relative changing rate was 0.9% per year. Bulk soil δ15N is determined by multiple N cycling processes, including gaseous N loss, net plant N uptake, leaching N loss, atmospheric N deposition and biological N fixation53,54. These processes have different effects on bulk soil δ15N, with the largest isotopic fractionation effects occurring in gaseous N loss (16~30‰), the second in net plant N uptake (5~10‰), the third in leaching N loss (1‰), and the least in atmospheric N deposition and biological N fixation (−2~0‰)53,54. Among these processes, atmospheric N deposition (both rate and δ15N, Supplementary Figs. 2–3) and leaching N loss (Fig. 3) did not exhibit significant changes during the detection period. Consequently, these two processes are supposed to have limited effects on bulk soil δ15N dynamics. Moreover, biological N fixation significantly increased during the past decade (P < 0.001; Fig. 3), which tended to depress bulk soil δ15N values because of the lower δ15N in biologically fixed N sources53,54. Accordingly, the increased bulk soil δ15N observed across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region should be largely driven by the enhanced gaseous N loss and/or the elevated plant N uptake. Overall, the simulated changes in plant N demand and ecosystem N loss (Fig. 3) were supported by the observed bulk soil δ15N dynamics (Fig. 4).

The progressive N limitation observed across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region contrasted with the traditional view that warming-induced permafrost thaw could eliminate vegetation N limitation in the circumpolar permafrost region by producing large amounts of available N through the acceleration of soil N mineralization and the release of originally frozen available N15,17,19. Such a difference could be related to the following two aspects. First, the soil N density (N storage per area) across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region (1.6 kg N m−2 to 3 m depth55) is much lower than that in the circumpolar permafrost region (4.6 ~ 7.5 kg N m−2 to 3 m depth56), which can lead to a lower available N supply through mineralization and thus is more likely to induce the enhanced vegetation N limitation. Second, the active layer thickness across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region (~2.4 m23) is two times deeper than that in the circumpolar permafrost region (~0.9 m57). Given that over 90% of plant roots are distributed within the 30 cm soil layer58, the deeper active layer thickness in this alpine permafrost region can restrict plants to use the released available N after permafrost thaw and thus is more likely to result in the enhanced vegetation N limitation.

In summary, based on isotopic observations from a resampling field investigation and simulations from a process-based biogeochemical model, this study explored ecosystem N dynamics across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. We found an enhanced vegetation N limitation across the study area over the last decade despite the increase in available N production. The progressive N limitation was associated with the joint enhancement in plant N demand and ecosystem N loss under current environmental changes, especially climate warming and CO2 enrichment. These results suggest that the enhanced N limitation may constrain the positive effects of climate warming and CO2 enrichment on vegetation productivity8. Despite that, microbial respiration can still be stimulated by the continuous climate warming59. Consequently, the Tibetan alpine permafrost region would turn from the current C sink45 to future C source with continuous environmental changes, which could then switch the feedback of C cycle to climate warming in an opposite direction.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted on the Tibetan Plateau, the largest alpine permafrost region around the world, with an area of ~1.35 × 106 km2 and a mean elevation over 4000 m22,23. Climate on this plateau is cold and dry22. The MAAT ranges between −4.1 and 7.4 °C, and the MAP varies from dozens of mm in the northwest of the plateau to ~700 mm in the southeast60. Due to the low temperature, permafrost is extensively developed and categorized as continuous, discontinuous, sporadic and isolated types across the plateau22. The mean active layer thickness was estimated at ~2.4 m (range: 1.3~4.6 m) along the Qinghai-Tibetan highway23. Alpine grassland is the main vegetation type across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region, with dominant species being Stipa purpurea and Carex moorcroftii for alpine steppe and Kobresia pygmaea and Kobresia humilis for alpine meadow45. Based on the World Reference Base for Soil Resources classification, the soil type across the study area is dominated by Xerosols and Cambisols45.

During the past decade, atmospheric N deposition (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), MAP (Supplementary Fig. 2) and soil moisture in the top 10 cm (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12, and Supplementary Note 3) kept stable across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Despite that, MAAT on the plateau has significantly increased with a rate of 0.05 °C per year since 198045, which is similar to the rate reported in the circumpolar permafrost region and twice as much as the global mean warming rate4. As air temperature rose, soil temperature was also detected to increase continuously in this alpine permafrost region23,45. Warming climate has induced extensive permafrost thaw, including top-down permafrost degradation and various thermokarst features, such as thermo-erosion gullies and thermokarst lakes23. In addition, the Tibetan alpine permafrost region has also experienced a linearly increased atmospheric CO2 concentration at a rate of 2.2 p.p.m.v. per year (Supplementary Fig. 2). These environmental changes make the Tibetan alpine permafrost region to be a natural laboratory to explore ecosystem N dynamics.

Original and repeated sampling

To detect temporal dynamics of ecosystem N cycle in the context of environmental changes across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region, a resampling field investigation, including an original field campaign and a repeated field campaign, was carried out across the study area during 2000s ~ 2010s (Fig. 1). To be specific, the original sampling campaign was conducted by the investigation team from Peking University during the period from 2001 to 200461. Based on this original campaign, 135 sites were investigated across the plateau (Fig. 1). After about 10 years, the resampling field campaign was performed by the investigation team from Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences in the year 2013 and 201445. With the record of geographic location (latitude and longitude) of a historical site investigated during the 2000s, the resampling site was preliminarily determined by a Global Position System with a decimetre precision (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Based on the soil pits excavated during the 2000s, the resampling site was then accurately located with the help of investigators who participated in the original campaign during the 2000s (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Eventually, 107 (~79%) of the original 135 sites were re-investigated (Fig. 1). These sites spanned about ~3000 km on the Tibetan Plateau, with longitude ranging from 80.8 to 120.1°E and latitude varying between 29.3 and 49.5°N (Fig. 1). Moreover, these resampling sites covered a wide range of climate gradients (MAAT: −3.1 ~ 4.4 °C; MAP: 103 ~ 694 mm) and major vegetation types (59 sites in alpine steppe and 48 sites in alpine meadow) across the study area.

Vegetation samples were collected in the same manner during the two sampling periods. Specifically, in the initial field campaign, a plot of 10 m × 10 m was set up after locating a site and then five quadrats (1 m × 1 m) were established at each corner and the centre of the plot. Within the five quadrats, vegetation communities (occurred species and the relative cover) were investigated and aboveground vegetation was collected for plant δ15N analysis. In the repeated field survey, once the original 10 m × 10 m plot was recovered (Supplementary Fig. 1b), we set five 1 m × 1 m quadrats next to the original quadrats, investigated vegetation communities (occurred species and the relative cover) and collected all the aboveground vegetation in each of the five quadrats for plant δ15N analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Consequently, the plant δ15N measured in our study represented the average isotopic signal of the vegetation community in the five quadrats with 1 × 1 m2 area. In other words, the isotopic signal represented information of all the plant species within the vegetation community. Considering the potential effects of shifts in vegetation community on plant δ15N dynamics observed in this study, we examined changes in vegetation composition indicated by species richness and Shannon–Wiener index (Supplementary Note 1) and detected the stable vegetation community over the detection period (Supplementary Fig. 5). Due to the potential effects of heavily mycorrhizal plant on the community average δ15N, we further analysed changes in species richness and the relative cover of five families that could be heavily colonized by mycorrhizae on the Tibetan Plateau (Gramineae, Leguminosae, Asteraceae, Cyperaceae and Rosaceae)33, and examined changes in the relative cover of the dominant species within the five families33 (Supplementary Note 1). Both the family- and species-level analyses confirmed that vegetation community composition was unchanged over the period from the 2000s to the 2010s (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), which eliminated the potential confounding effects of vegetation community shifts on the plant δ15N dynamics observed in this study.

Similar to vegetation samples, the corresponding approaches used to collect soil samples were also consistent between the two sampling periods. Specifically, soil samples used to measure N isotope, N content as well as other soil properties (texture, pH, soil organic carbon (SOC) content) were collected within the top 10 cm layer in three quadrats along a diagonal within each resampling site (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Soil samples used to determine bulk density were collected within the 10 cm depth with standard 100 cm3 steel cylinders in three quadrats along a diagonal within each resampling site45. Besides the identical investigation method and the stable vegetation community (Supplementary Figs. 5–7), the topography and management practices were also unchanged during the detection period for each of the 107 paired sampling sites45.

Elemental and stable isotope analyses

To explore changes in ecosystem N cycle, we measured δ15N values of plant and bulk soil with samples collected through the large-scale resampling investigations. In our study, site-level plant δ15N measurement was conducted based on the five vegetation samples collected over the five quadrats (1 m × 1 m) within a sampling plot (10 m × 10 m; Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, at each sampling site, plant samples were collected from each of the five 1 × 1 m2 quadrats, dried to a constant weight at 65 °C and weighed as aboveground biomass separately. The dried plant samples were then ground using a ball mill (Mixer Mill MM 400, Retsch, Germany) for plant δ15N analysis. In addition, the collected soil samples were air dried, passed through a 2 mm sieve (removing gravel and coarse roots), processed to remove fine roots and ground with a ball mill (Mixer Mill MM 400, Retsch, Germany). With the treated plant and soil samples, we measured plant and bulk soil δ15N values using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (SerCon 20–22, Crewe, UK), analysed plant and soil N contents with an elemental analyser (Vario EL Ш, Elementar, Germany), and determined soil P contents with an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICAP 6300 ICP-OES Spectrometer, Thermo Scientific, USA). To avoid errors in measurements, both δ15N values and element contents during the two sampling periods were determined at the same time with the same instruments.

Model simulation

To further examine ecosystem N dynamics on the basis of observations from large-scale resampling investigation, we simulated the key ecosystem N cycling processes for the 107 resampling sites with DNDC [http://www.dndc.sr.unh.edu/], a process-based biogeochemical model. DNDC has been widely tested and applied around the world [http://www.globaldndc.net/information/publications-i-3.html], especially for the simulation of ecosystem N dynamics24,25, and has also been demonstrated to perform well across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region62,63.

In this study, we first validated the DNDC model in terms of simulating ecosystem-atmosphere nitrous oxide (N2O) fluxes. Specifically, we collected N2O fluxes measurements from published studies across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region, and obtained 58 N2O observations from 22 sites (Supplementary Fig. 15a) in 18 studies (Supplementary Methods). We also synthesized other data from the above-mentioned literature (Supplementary Methods) and other associated literature64–67 to drive the model simulation, including vegetation type, plant biomass, plant C:N ratio, soil texture, soil bulk density, soil pH, SOC content and soil C:N ratio. To drive the model simulation, we further acquired data for atmospheric CO2 concentration, annual rate of atmospheric N deposition, daily meteorology and thermal degree days. Among them, the atmospheric CO2 concentration, observed at the Waliguan (a global atmospheric background station), was obtained from the Chinese Research Network or Special Environment and Disaster [http://www.crensed.ac.cn]. Atmospheric N deposition rate was obtained from a national-scale spatiotemporal dataset68 if it was not provided in the original literature. The daily meteorological data, including mean temperature, maximum temperature, minimum temperature and precipitation, were derived from the nearest meteorological station [http://data.cma.cn/] close to the N2O observation site. The thermal degree days were calculated by summing the daily mean temperature higher than 0 °C38. Based on the above-mentioned dataset, N2O fluxes were simulated by the DNDC model. With the simulated and observed N2O emissions, the model performance was evaluated on the basis of the 1 : 1 line plot (Supplementary Fig. 15b) and four indicators which included R2 (coefficient of determination; Eq. 1), RMSE (root mean square error; Eq. 2), RMD (relative mean deviation; Eq. 3) and ME (model efficiency; Eq. 4)62,63.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where in Si and Oi are simulated and observed values, and are their averages and n indicates the number of simulation-observation pairs. The model validation showed that all the data points constituted by the simulated and observed N2O emissions were well distributed near the 1 : 1 line (Supplementary Fig. 15b), demonstrating good model performance across the study area.

Using the validated model, we conducted simulations for the 107 resampling sites during the period from 1980 to 2015. Before simulations, credible data were collected as model inputs, including atmospheric CO2 concentration, annual atmospheric N deposition rate, daily meteorological data, vegetation type, plant biomass, plant C : N ratio, soil texture, soil bulk density, soil pH, SOC content and soil C : N ratio. Among them, the annual atmospheric CO2 concentration, annual atmospheric N deposition rate and daily meteorological data were derived from the Chinese Research Network or Special Environment and Disaster [http://www.crensed.ac.cn], a spatiotemporal dataset of atmospheric N deposition in China68 and China Meteorological Administration [http://data.cma.cn/], respectively. The vegetation type for each site was determined based on the vegetation community investigation during the resampling campaign. Data for plant biomass, plant C : N ratio, soil texture, bulk density, pH, SOC content and soil C : N ratio were derived from direct measurements. Of them, plant C content was measured with an elemental analyser (Vario EL Ш, Elementar, Germany). Soil texture was determined with a laser particle size analyser (Malvern Masterizer 2000, Malvern, UK) after removing soil organic matter and carbonate. Soil bulk density was examined by drying the samples collected with standard steel cylinders at 105 °C. Soil pH was determined using a pH electrode (PB-10, Sartorius, Germany) in a 1 : 2.5 soil-to-deionized water mixture. The SOC content was analysed with the Walkley–Black method61. With the above-mentioned dataset, simulations were conducted with the DNDC model. After that, the model was further validated with the observed soil N density (N storage per area, 0–10 cm, Eq. 5) and aboveground plant N pool (the product of aboveground biomass and the corresponding N content), based on the combination of 1:1 line plots and the four model performance indicators mentioned above (i.e., R2, RMSE, RMD and ME). The validation results showed that both soil N density and aboveground plant N pool were well distributed near the 1 : 1 line and the four indicators (i.e., R2, RMSE, RMD, and ME) illustrated good model performance (Supplementary Fig. 16).

| 5 |

In Eq. 5, soil N density (SND, kg N m−2) was calculated based on soil thickness (Ti, cm), bulk density (BDi, g cm−3), soil total N content (TNi, g kg−1) and >2 mm rock content (Ci, %)55. In addition, soil moisture (10 cm depth) simulated by the DNDC model, determined jointly by precipitation and other hydrological processes69, was also validated with the measured values across the 107 resampling sites. The data-model comparison revealed that the DNDC model could well capture the observed soil moisture across the investigated sites (Supplementary Fig. 17). Furthermore, both the simulated and observed surface soil water-filled pore space experienced no significant changes over the period from the 2000s to the 2010s (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12), demonstrating that the DNDC model could also accurately characterize soil moisture dynamics across the study area.

Statistical analyses

To determine whether N cycling variables exhibited significant differences during the detection period, we conducted statistical tests with the linear mixed-effects model (LMM). LMM is an extension of simple linear model, which can effectively remove the random effects for non-independent data45. In this study, LMMs were used to explore changes in plant δ15N, plant N stress index, the production of available N (soil N mineralization and biological N fixation), plant N demand (plant N pool and plant N uptake rate), ecosystem N loss (total N loss, gaseous N loss and leaching N loss) and bulk soil δ15N over the detection period. For all the analyses with LMM, the fixed effect was year and the random effect was sampling site. Data normality was tested before the LMM analyses, and log-transformation was performed when necessary. All the analyses were conducted in R 3.5.1 with the lme4 package70.

To disentangle effects of environmental changes on N cycling processes, factorial analyses were conducted with the DNDC simulations. Four simulation experiments were carried out for each of the 107 resampling sites: (i) constant atmospheric CO2 concentration with normal changes in other factors; (ii) constant temperature with normal changes in other factors; (iii) constant precipitation with normal changes in other factors; and (iv) normal changes in all factors. After all the simulations, we calculated the differences between the target variable in one of the four controlling simulation experiments and the target variable in experiment (iv) for each resampling site. Finally, we averaged the calculated differences among the 107 resampling sites to reflect the impact of different environmental changes on the dynamics of N cycling processes.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the members of Peking University Sampling Teams (2001~2004) and IBCAS Sampling Teams (2013~2014) for field investigation and sampling. We appreciate Conghong Huang from the State University of New York for his help in collecting remote-sensing data, and Xuning Liu and Weijie Xu from Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IBCAS) for their assistance in synthesizing mycorrhizal data. We thank Plant Science Facility of the IBCAS for elemental and stable isotope analyses. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31825006, 31988102 and 91837312), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) programme (2019QZKK0106 and 2019QZKK0302) and Key Research Programme of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDB-SSW-SMC049).

Author contributions

Y.Y. and D.K. designed research. Y.Y., C.J. and J.F. conducted the original sampling during the period of 2001~2004, G.Y., F.L. and Y.Y. performed the resampling in 2013~2014. D.K., C.M., X.F., D.Z., Q.W.Z., Y.P. and Y.Y. performed laboratory analyses. D.K., J.D., Q.A.Z., X.-R., S.L. and X.Z. conducted model simulations. D.K., Y.Y., Y.F. and X.L. analysed data and integrated results. D.K. and Y.Y. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Data availability

All plant and soil δ15N data used in this study are available as a supplementary file (Supplementary Data 1). Additional data are available from the corresponding author (Dr. Yuanhe Yang) upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communication thanks Jeffrey Heikoop and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-17169-6.

References

- 1.Schuur EAG, Mack MC. Ecological response to permafrost thaw and consequences for local and global ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2018;49:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Köchy M, Hiederer R, Freibauer A. Global distribution of soil organic carbon—Part 1: Masses and frequency distributions of SOC stocks for the tropics, permafrost regions, wetlands, and the world. Soil. 2015;1:351–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biskaborn, B. K. et al. Permafrost is warming at a global scale. Nat. Commun. 10, 10.1038/s41467-018-08240-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Schuur EAG, et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature. 2015;520:171–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Natali SM, et al. Large loss of CO2 in winter observed across the northern permafrost region. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019;9:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0592-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knoblauch C, Beer C, Liebner S, Grigoriev MN, Pfeiffer EM. Methane production as key to the greenhouse gas budget of thawing permafrost. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018;8:309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turetsky MR, et al. Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koven CD, Lawrence DM, Riley WJ. Permafrost carbon-climate feedback is sensitive to deep soil carbon decomposability but not deep soil nitrogen dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3752–3757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415123112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire AD, et al. Dependence of the evolution of carbon dynamics in the northern permafrost region on the trajectory of climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:3882–3887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719903115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kicklighter, D. W., Melillo, J. M., Monier, E., Sokolov, A. P. & Zhuang, Q. L. Future nitrogen availability and its effect on carbon sequestration in Northern Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 10, 10.1038/s41467-019-10944-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chapin, F. S. III, Matson, P. A. & Vitousek, P. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

- 12.McLauchlan KK, Craine JM, Oswald WW, Leavitt PR, Likens GE. Changes in nitrogen cycling during the past century in a northern hardwood forest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7466–7470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701779104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craine JM, et al. Isotopic evidence for oligotrophication of terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1735–1744. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koven CD, et al. Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14769–14774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103910108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keuper F, et al. A frozen feast: thawing permafrost increases plant-available nitrogen in subarctic peatlands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012;18:1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finger RA, et al. Effects of permafrost thaw on nitrogen availability and plant-soil interactions in a boreal Alaskan lowland. J. Ecol. 2016;104:1542–1554. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon VG, et al. Nitrogen availability increases in a tundra ecosystem during five years of experimental permafrost thaw. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016;22:1927–1941. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmon VG, et al. Adding depth to our understanding of nitrogen dynamics in permafrost soils. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018;123:2497–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beermann F, et al. Permafrost thaw and liberation of inorganic nitrogen in Eastern Siberia. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 2017;28:605–618. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt RE, Taylor DL, Genet H, McGuire AD, Mack MC. Below-ground plant traits influence tundra plant acquisition of newly thawed permafrost nitrogen. J. Ecol. 2019;107:950–962. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natali SM, Schuur EAG, Rubin RL. Increased plant productivity in Alaskan tundra as a result of experimental warming of soil and permafrost. J. Ecol. 2012;100:488–498. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang T, Barry RG, Knowles K, Heginbottom JA, Brown J. Statistics and characteristics of permafrost and ground-ice distribution in the Northern Hemisphere. Polar. Geogr. 2008;31:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu QB, Zhang TJ. Changes in active layer thickness over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1995 to 2007. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010;115:D09107. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li CS, Frolking S, Frolking TA. A model of nitrous oxide evolution from soil driven by rainfall events: 1. Model structure and sensitivity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1992;97:9759–9776. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, C. S. Biogeochemistry: Scientific Fundamentals and Modelling Approach. (Tsinghua Univ. Press, 2016).

- 26.Craine JM, et al. Global patterns of foliar nitrogen isotopes and their relationships with climate, mycorrhizal fungi, foliar nutrient concentrations, and nitrogen availability. N. Phytol. 2009;183:980–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLauchlan KK, Ferguson CJ, Wilson IE, Ocheltree TW, Craine JM. Thirteen decades of foliar isotopes indicate declining nitrogen availability in central North American grasslands. N. Phytol. 2010;187:1135–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobbie JE, Hobbie EA. 15N in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and carbon flux rates in Arctic tundra. Ecology. 2006;87:816–822. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[816:nisfap]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbie EA, Hogberg P. Nitrogen isotopes link mycorrhizal fungi and plants to nitrogen dynamics. N. Phytol. 2012;196:367–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houlton BZ, Sigman DM, Schuur EAG, Hedin LO. A climate-driven switch in plant nitrogen acquisition within tropical forest communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8902–8906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609935104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobbie EA, Hobbie JE. Natural abundance of N-15 in nitrogen-limited forests and tundra can estimate nitrogen cycling through mycorrhizal fungi: A review. Ecosystems. 2008;11:815–830. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schimel JP, Bennett J. Nitrogen mineralization: Challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology. 2004;85:591–602. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Wang X, Wang Q, Jin L. Advances in the study of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in high altitude and cold habitats on Tibetan Plateau. J. Fungal Res. 2017;15:58–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treseder KK. A meta-analysis of mycorrhizal responses to nitrogen, phosphorus, and atmospheric CO2 in field studies. N. Phytol. 2004;164:347–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jayne B, Quigley M. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhiza on growth and reproductive response of plants under water deficit: a meta-analysis. Mycorrhiza. 2014;24:109–119. doi: 10.1007/s00572-013-0515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmore AJ, Nelson DM, Craine JM. Earlier springs are causing reduced nitrogen availability in North American eastern deciduous forests. Nat. Plants. 2016;2:16133. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLauchlan, K. K. et al. Centennial-scale reductions in nitrogen availability in temperate forests of the United States. Sci. Rep. 7, 10.1038/s41598-017-08170-z (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Li, C. User’s Guide for the DNDC Model. (Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans and Space, University of New Hampshire, 2012).

- 39.Zhang Y, Li CS, Zhou XJ, Moore B. A simulation model linking crop growth and soil biogeochemistry for sustainable agriculture. Ecol. Model. 2002;151:75–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guest G, et al. Comparing the performance of the DNDC, Holos, and VSMB models for predicting the water partitioning of various crops and sites across Canada. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2018;98:212–231. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo Y, et al. Progressive nitrogen limitation of ecosystem responses to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide. BioScience. 2004;54:731–739. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finzi AC, et al. Increases in nitrogen uptake rather than nitrogen-use efficiency support higher rates of temperate forest productivity under elevated CO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14014–14019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706518104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, et al. Ecological change on the Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2015;60:3048–3056. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang GL, Zhang YJ, Dong JW, Xiao XM. Green-up dates in the Tibetan Plateau have continuously advanced from 1982 to 2011. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:4309–4314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210423110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding J, et al. Decadal soil carbon accumulation across Tibetan permafrost regions. Nat. Geosci. 2017;10:420–424. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piao SL, et al. Impacts of climate and CO2 changes on the vegetation growth and carbon balance of Qinghai-Tibetan grasslands over the past five decades. Glob. Planet Change. 2012;98-99:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bai E, et al. A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. N. Phytol. 2013;199:441–451. doi: 10.1111/nph.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dawes MA, Schleppi P, Hattenschwiler S, Rixen C, Hagedorn F. Soil warming opens the nitrogen cycle at the alpine treeline. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017;23:421–434. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang XZ, Shen ZX, Fu G. A meta-analysis of the effects of experimental warming on soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics on the Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015;87:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xue K, et al. Tundra soil carbon is vulnerable to rapid microbial decomposition under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016;6:595–600. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouwman AF, Boumans LJM, Batjes NH. Estimation of global NH3 volatilization loss from synthetic fertilizers and animal manure applied to arable lands and grasslands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2002;16:1024. [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Groenigen KJ, Osenberg CW, Hungate BA. Increased soil emissions of potent greenhouse gases under increased atmospheric CO2. Nature. 2011;475:214–216. doi: 10.1038/nature10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houlton BZ, Bai E. Imprint of denitrifying bacteria on the global terrestrial biosphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21713–21716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912111106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, C. et al. Aridity threshold in controlling ecosystem nitrogen cycling in arid and semi-arid grasslands. Nat. Commun. 5, 10.1038/ncomms5799 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Kou D, et al. Spatially-explicit estimate of soil nitrogen stock and its implication for land model across Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;650:1795–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harden JW, et al. Field information links permafrost carbon to physical vulnerabilities of thawing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012;39:L15704. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Chen WJ, Riseborough DW. Temporal and spatial changes of permafrost in Canada since the end of the Little Ice. Age. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2006;111:D22103. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Y, Fang J, Ji C, Han W. Above- and belowground biomass allocation in Tibetan grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 2009;20:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crowther TW, et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature. 2016;540:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kou D, et al. Diverse responses of belowground internal nitrogen cycling to increasing aridity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018;116:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y, et al. Storage, patterns and controls of soil organic carbon in the Tibetan grasslands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008;14:1592–1599. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo J, Chen Y, Zhu W, Zhou P. Modeling climate change effects on soil respiration in three different stages of primary succession in deglaciated region on Gongga Mountain, China. Scand. J. Forest Res. 2013;28:363–372. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W, Zhang F, Qi J, Hou F. Modeling impacts of climate change and grazing effects on plant biomass and soil organic carbon in the Qinghai-Tibetan grasslands. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:5455–5470. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peng YF, et al. Soil temperature dynamics modulate N2O flux response to multiple nitrogen additions in an alpine steppe. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018;123:3308–3319. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu HY, et al. Shifting plant species composition in response to climate change stabilizes grassland primary production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:4051–4056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700299114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao YZ, et al. Belowground net primary productivity and biomass allocation of a grassland in Inner Mongolia is affected by grazing intensity. Plant Soil. 2008;307:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu ZM, et al. Effects of vegetation control on ecosystem water use efficiency within and among four grassland ecosystems in China. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008;14:1609–1619. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jia Y, et al. A spatial and temporal dataset of atmospheric inorganic nitrogen wet deposition in China (1996–2015) China Sci. Data. 2019;4:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deng J, et al. Modeling nitrogen loadings from agricultural soils in southwest China with modified DNDC. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2011;116:G02020. [Google Scholar]

- 70.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All plant and soil δ15N data used in this study are available as a supplementary file (Supplementary Data 1). Additional data are available from the corresponding author (Dr. Yuanhe Yang) upon reasonable request.