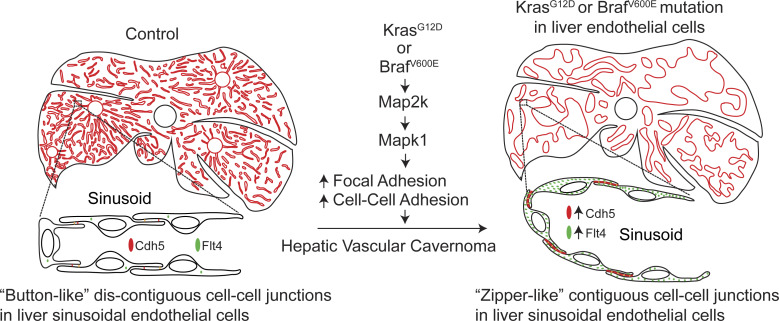

This study demonstrates endothelial KRAS or BRAF gain-of-function mutations as a causal mechanism for hepatic vascular cavernomas, the most common benign tumor of the liver. RAS-MAPK1 signaling inhibition rescues hepatic vascular cavernoma formation in endothelial KRASG12D- or BRAFV600E-expressing mice.

Abstract

Human hepatic vascular cavernomas, the most common benign tumor of the liver, were described in the mid-1800s, yet the mechanisms for their formation and effective treatments remain unknown. Here, we demonstrate gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes within liver endothelial cells as a causal mechanism for hepatic vascular cavernomas. We identified gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes in pathological liver tissue samples from patients with hepatic vascular cavernomas. Mice expressing these human KRASG12D or BRAFV600E mutations in hepatic endothelial cells recapitulated the human hepatic vascular cavernoma phenotype of dilated sinusoidal capillaries with defective branching patterns. KRASG12D or BRAFV600E induced “zipper-like” contiguous expression of junctional proteins at sinusoidal endothelial cell–cell contacts, switching capillaries from branching to cavernous expansion. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of the endothelial RAS–MAPK1 signaling pathway rescued hepatic vascular cavernoma formation in endothelial KRASG12D- or BRAFV600E-expressing mice. These results uncover a major cause of hepatic vascular cavernomas and provide a road map for their personalized treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sporadic cavernous hemangiomas or vascular cavernomas of the liver, classified as slow-flow venous malformations, are the most common benign tumor of the liver (Tait et al., 1992; Graivier et al., 1967). These cavernomas are composed of dilated endothelial-lined vascular spaces that are irregular in arrangement and sizes (Hamilton and Holmes, 1950). Large hepatic vascular cavernomas, >5 cm in diameter, often cause lethal complications such as hepatic rupture, consumption coagulopathy, and cardiac failure (Hendrick, 1948; Graivier et al., 1967; Ribeiro et al., 2010). Although Virchow (1863) and Frerichs (1860) described hepatic vascular cavernomas as a distinct clinical entity in the mid-1800s, their genetic etiology, molecular mechanism, and effective treatment remain undefined.

Results

Human patients with hepatic vascular cavernomas exhibit somatic gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes in pathological liver tissue samples

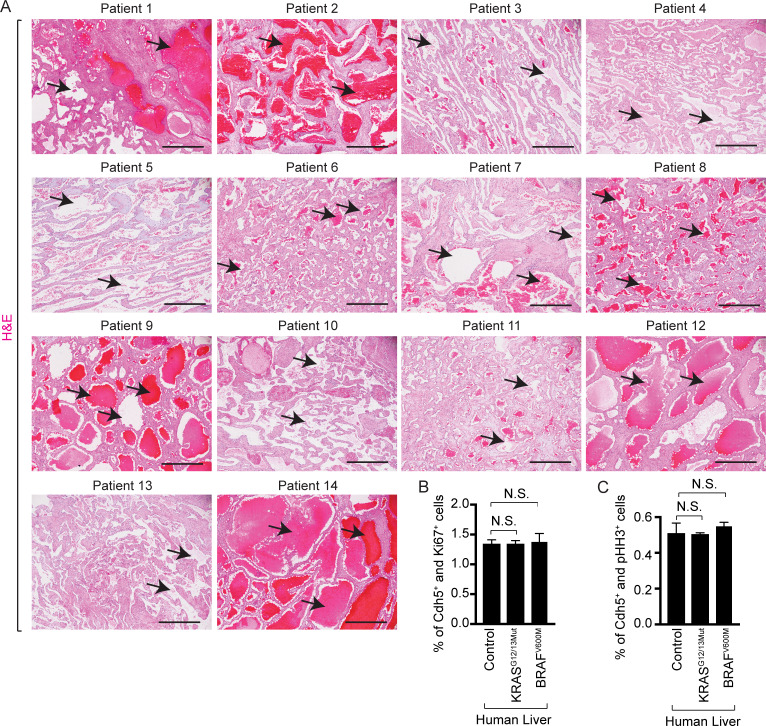

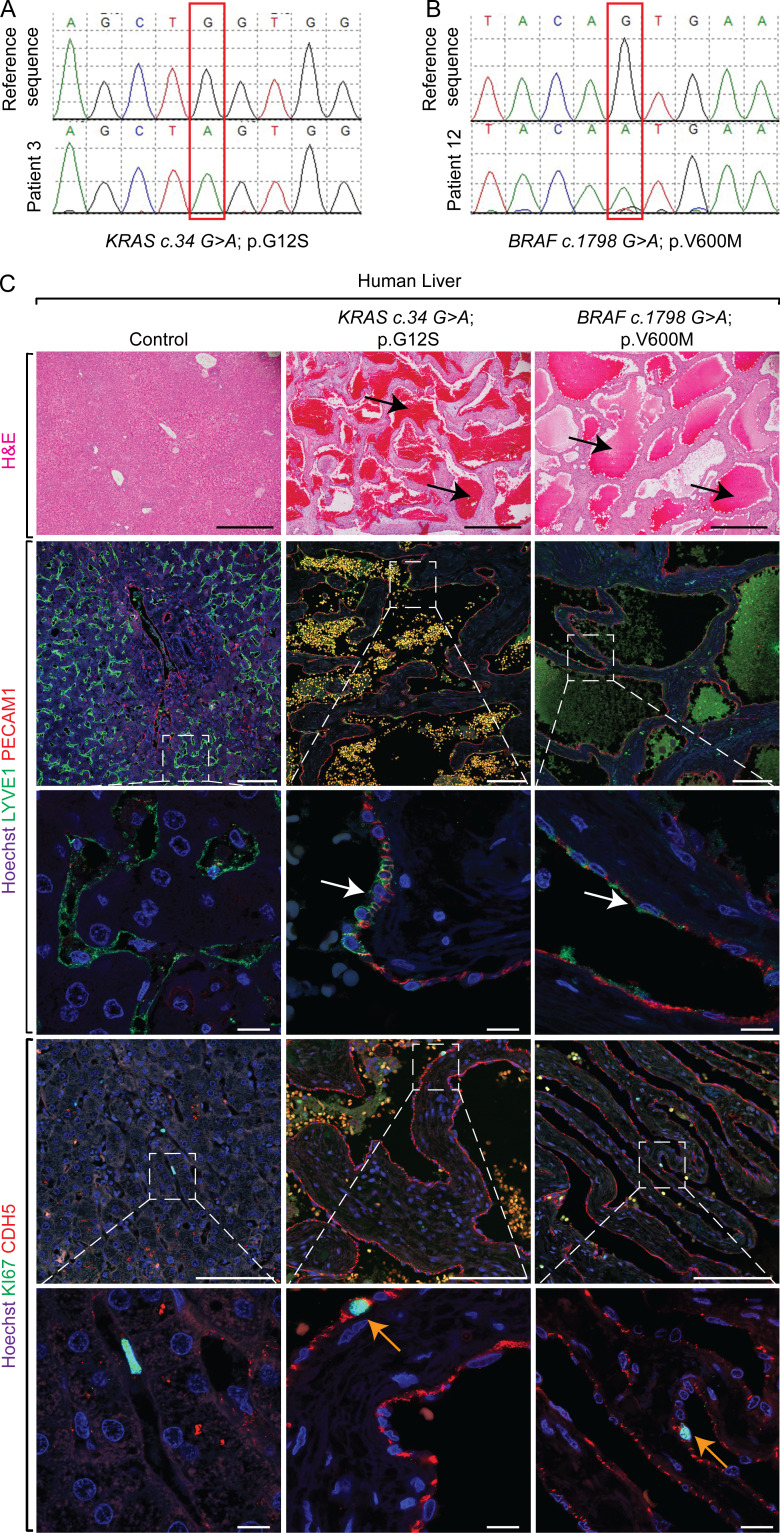

Using next-generation deep sequencing and Sanger sequencing, along with bridged nucleic acid (BNA) clamp–mediated PCR assay, we sequenced hepatic vascular cavernoma tissue samples from 39 patients diagnosed with hepatic cavernous hemangioma or hemangioma (Table 1 and Fig. S1 A). Our analyses revealed KRAS and/or BRAF gain-of-function pathogenic mutations in ∼36% of cases (14 of 39; Table 1 and Fig. 1, A and B). Activating KRAS mutations (n = 10) were found at hotspot codon 12 and/or 13: p.Gly-Asp and/or p.Gly-Ser with an allele frequency ranging from ∼0.1 to 0.75% (Table 1 and Fig. 1 A). Among these, four cases exhibited mosaic KRAS mutations. BRAF gain-of-function mutations (n = 3) were identified at hotspot codon 600: p.Val600Met with an allele frequency ∼0.2% (Table 1 and Fig. 1 B). Interestingly, one case revealed activating mutations in both KRAS (p.Gly12Ser) and BRAF (p.Val600Met) with a variant allele load of ∼0.2% (Table 1). These hepatic lesions exhibited cavernous spaces filled with erythrocytes and lined by lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor (LYVE1)+/Cadherin 5 (CDH5)+/ platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM1)+ endothelial cells, malformed sinusoidal capillary vessels, and normal endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 1 C and Fig. S1, B and C).

Table 1. KRAS and BRAF mutations identified in individuals with hepatic cavernous hemangiomas.

| Patient | Pathological feature/size/location | Age (yr) | Sex | Next generation sequencing (MAF%) | BNA clamp | Sanger sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cavernous hemangioma (6.5 cm in greatest dimension), right lobe | 62 | Female | K-RAS p.G12D (0.75%) | Mutant | ND |

| 2 | Hemangioma of the liver (7.0 × 7.0 × 3.5 cm), left lateral lobe | 37 | Male | K-RAS p.G12S (0.1%)a; K-RAS p.G12D (0.1%) | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12S |

| 3 | Cavernous hemangioma (7 cm in greatest dimension), right lobe | 40 | Female | K-RAS p.G12S (0.2%) | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12S |

| 4 | Two hemangiomas (1.9 and 1.1 cm), right lobe | 57 | Male | K-RAS p.G13D (0.4%) K-RAS p.G13S (0.47%) | Mutant | ND |

| 5 | Cavernous hemangioma with scattered areas of sclerosis (6.3 cm), left lobe | 87 | Male | K-RAS p.G12D (0.68%) | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12C; K-RAS p.G12S |

| 6 | Cavernous hemangioma (10 cm) | 48 | Female | K-RAS p.G12S (0.31%) | Mutant | ND |

| 7 | Cavernous hemangioma with foci of necrosis and fibrosis (8.5 × 6 × 2 cm) | 43 | Female | K-RAS p.G12S (0.3%) BRAF p.V600M (0.17%)b | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12S; K-RAS p.G12D |

| 8 | Cavernous hemangioma of liver with extensive fibrosis, thrombi, and infarct (17.5 × 9 × 9 cm) | 48 | Male | K-RAS p.G12S (0.35%); K-RAS p.G12D (0.57%) K-RAS p.G13S (0.5%); K-RAS p.G13D (0.43%) | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12S; K-RAS p.G12V |

| 9 | Cavernous hemangioma (1.3 cm) | 50 | Female | K-RAS p.G12S (0.32%) | Mutant | ND |

| 10 | Cavernous hemangioma with focal degenerative change, segments 2 and 3 | 40 | Female | K-RAS p.G12S(0.25); K-RAS p.G13S (0.32%) | Mutant | ND |

| 11 | Cavernous hemangioma partially sclerosed (19.0 cm) | 42 | Male | K-RAS p.G13D (0.18%) | Mutant | K-RAS p.G12R |

| 12 | Cavernous hemangioma (1.5 cm), right lobe | 46 | Female | BRAF p.V600M (0.15%) | Mutant | BRAF p.V600M |

| 13 | Hemangioma (6.1 cm), left lobe | 55 | Female | BRAF p.V600M (0.2%) | Mutant | ND |

| 14 | Hepatic hemangioma (2.5 cm) | 42 | Female | BRAF p.V600M (0.18%) | Mutant | ND |

MAF, mutant allele frequency.

Manually verified in NextGENe alignment viewer.

Sanger sequence not determined.

Figure S1.

Human patients with somatic gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes exhibit hepatic vascular cavernomas. (A) H&E staining on pathological human liver sections shows cavernous spaces filled with erythrocytes (black arrows), n = 14. Sequencing of these 14 human liver tissue samples with cavernous vascular malformations identified a somatic mutation in KRAS or BRAF genes. Scale bar: 500 µm. (B and C) Quantitation of proliferating Cdh5+ and Ki67+ (B) or pHH3+ (C) cells in control (n = 4), KRASG12/13Mut (n = 11), and BRAFV600M (n = 3) mutant human livers (ages 37 to 87 yr). Unpaired t test, P > 0.6. Two independent experiments. Data represent the mean ± SEM. N.S., not significant.

Figure 1.

Human patients with hepatic vascular cavernomas exhibit somatic gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes in pathological liver tissue samples. (A and B) Sanger sequencing of human hepatic vascular cavernoma tissue samples identified a somatic mutation (red box), c.34G>A (p.G12S) in KRAS (A) or c.1798G>A (p.V600M) in BRAF (B) genes. (C) H&E staining on pathological human liver sections shows cavernous spaces filled with erythrocytes (black arrows; n = 14). Coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) shows contribution of LYVE1+ (green) and PECAM1+ (red) endothelial cells (white arrows) to hepatic cavernous vascular malformations (n = 7). KI67 (green) and CDH5 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on pathological human liver sections shows normal proliferation of CDH5+ sinusoidal endothelial cells lining cavernous vascular malformations (orange arrows; control, n = 4; KRASG12/13Mut, n = 11; BRAFV600M, n = 3). All experimental data verified in at least two independent experiments. Scale bars: 500 µm (top row), 100 µm (second and fourth rows from top), and 10 µm (third and fifth rows from top).

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations cause hepatic vascular cavernomas in mice

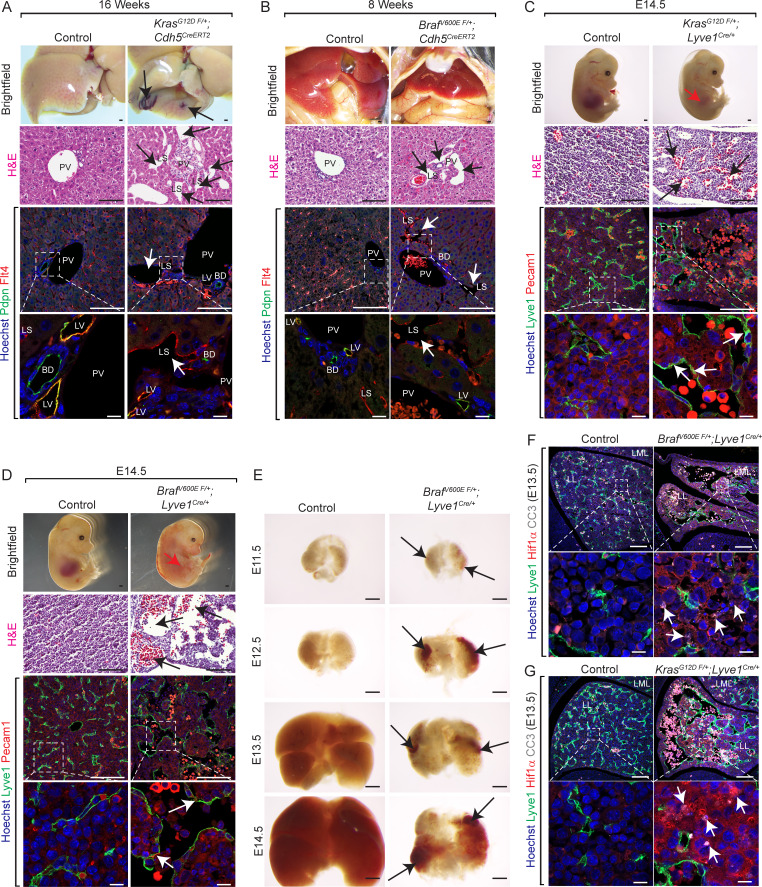

Dysregulation of endothelial cells underlies the formation of vascular anomalies. To investigate the endothelial cell–specific role of KRAS or BRAF gain-of-function mutations in hepatic vascular cavernomas, we generated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 mice, in which tamoxifen administration activates the KrasG12D or BrafV600E allele expression specifically in Cdh5+ endothelial cells. Tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 mice rapidly developed sinusoidal capillary dilation and hepatic vascular cavernomas with complete penetrance at perinatal and adult stages (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S2, A–D). Histological and immunological analyses of tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 mice revealed cavernous, malformed, erythrocyte-filled liver sinusoidal spaces lined by Lyve1+/Cdh5+/Pecam1+ endothelial cells, and normal endothelial cell proliferation consistent with human phenotype (Fig. 2, A and B; Fig. S2, A–D; and Fig. S3, A–D). In addition, Podoplanin (Pdpn)+ lymphatic vessels appear normal and do not contribute to hepatic vascular cavernomas in tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Further, we expressed KRASG12D or BRAFV600E allele in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells of developing murine embryos using Lyve1-Cre (KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre) mice (Fig. 2, C–E). These embryos exhibited complete embryonic lethality, reduced liver size, and fully penetrant hepatic vascular cavernomas phenotype without major changes in endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 2, C–E; Fig. S2, E–H; and Fig. S3, E–H). KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryonic livers revealed hypoxia and apoptosis in clusters of nonendothelial hepatic cells near vascular cavernomas, thus limiting growth and expansion of fetal liver (Fig. 2, F and G). Tissue-resident macrophages express Lyve1; hence, we expressed KRASG12D or BRAFV600E allele in macrophages of developing murine embryos using LysM-Cre (KrasG12D F/+; LysMCre and BRAF-V600ELysM-Cre). KrasG12D F/+; LysMCre and BRAF-V600ELysM-Cre embryos appeared normal and displayed normal sinusoidal and hepatic development (Fig. S4, A and B). Similarly, tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 mice did not reveal sinusoidal capillary dilation and vascular cavernomas in spleen, an organ with fenestrated endothelium (Fig. S4, C and D). Together, these results suggest that KRAS or BRAF gain-of-function mutations within sinusoidal endothelial cells cause hepatic vascular cavernomas.

Figure 2.

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations cause hepatic vascular cavernomas in mice. (A and B) Dissected livers and H&E-stained liver frontal sections show vascular cavernomas (black arrows) in tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (A) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (B) mice (n = 3). Pdpn (green) and Flt4 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (A) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (B) liver sections shows contribution of Flt4+ and Pdpn-negative endothelial cells to hepatic vascular cavernomas (white arrows). n = 3. Scale bars: 500 µm (top row), 100 µm (second and third row from top), and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (C and D) Dissected KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre (D) embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) embryos show reduced liver size (red arrow; n = 3). H&E-stained KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre (D) E14.5 liver frontal sections show vascular cavernomas (black arrows; n = 3). Coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) shows contribution of Lyve1+ (green) and Pecam1+ (red) endothelial cells (white arrows) to hepatic vascular cavernomas. n = 3. Scale bars: 500 µm (top row), 100 µm (second and third row from top), and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (E) Dissected BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers show reduction in liver size at E13.5 and progressive development of hepatic vascular cavernomas (black arrows). n = 3. Scale bars: 500 µm. (F) Lyve1 (green), Hif1α (red), and Cleaved caspase 3 (CC3, white) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre (F) and KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre (G) E13.5 liver frontal sections shows hypoxia and apoptosis in clusters of nonendothelial hepatic cells near vascular cavernomas (white arrows). n = 3. Scale bars: 100 µm (top row) and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. Littermates were used as controls for all experiments. All experimental data verified in at least two independent experiments. BD, bild duct; LL, left lobe; LML, left medial lobe; LS, liver sinusoid; LV, lymphatic vessel; PV, portal vein.

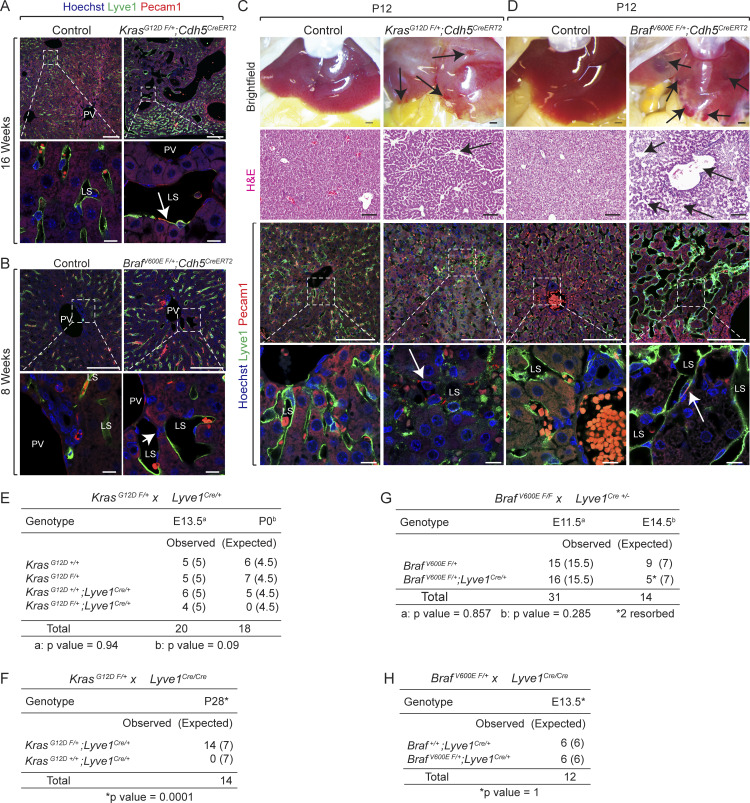

Figure S2.

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations cause hepatic vascular cavernomas and embryonic lethality in mice. (A and B) Lyve1 (green) and Pecam1 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on tamoxifen-treated adult KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (A) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (B) liver sections shows contribution of Lyve1+ and Pecam1+ endothelial cells to hepatic vascular cavernomas (white arrows). n = 3. Scale bars: 100 μm (top row) and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (C and D) Dissected livers and H&E-stained liver frontal sections show vascular cavernomas (black arrows) in tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) neonatal mice. Lyve1 (green) and Pecam1 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) liver sections shows contribution of Lyve1+ and Pecam1+ endothelial cells to hepatic vascular cavernomas (white arrows). n = 3. P, postnatal day. Scale bars: 500 μm (top row), 100 µm (second and third rows from top), and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (E and F) Genotyping tables of embryos or pups derived from KrasG12D F/+ mice crossed with either Lyve1Cre/+ (E) or Lyve1Cre/Cre (F) mice. (G and H) Genotyping tables of embryos derived from BrafV600E F/F (G) or BrafV600E F/+ (H) mice crossed with either Lyve1Cre/+ (G) or Lyve1Cre/Cre (H) mice. χ2 P value 0.94 (E, E13.5), 0.09 (E, P0), 0.0001 (F), 0.857 (G, E11.5), 0.285 (G, E14.5), 1.0 (H). LS, liver sinusoid; PV, portal vein.

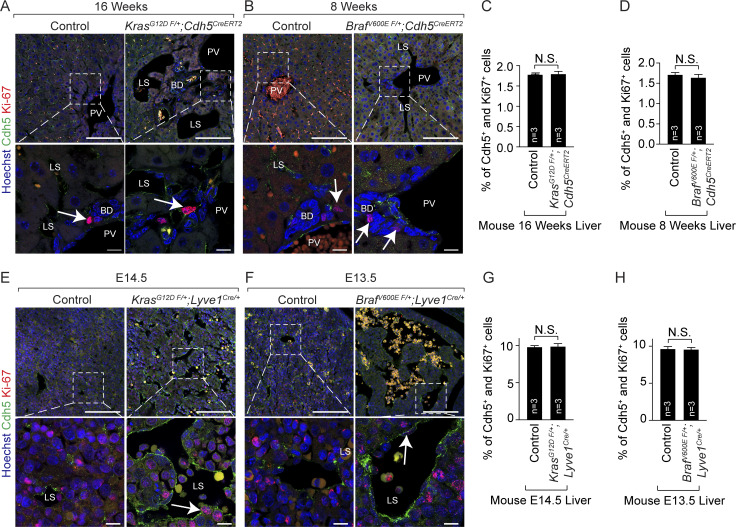

Figure S3.

Mice with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations exhibit normal proliferation of hepatic endothelial cells. (A and B) Ki67 (red) and Cdh5 (green) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (A) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (B) adult murine liver sections. White arrows show Ki67+ cells. n = 3. Scale bars: 100 µm (top row) and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. FDR, false discovery rate. (C and D) Quantitation of proliferating Cdh5+ cells in tamoxifen-treated control, KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C), and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) embryonic murine livers. n = 3. Unpaired t test, P > 0.8 (C) and P > 0.4 (D). Two independent experiments. Data represent the mean ± SEM. (E and F) Ki67 (red) and Cdh5 (green) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre/+ (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre/+ (D) embryonic murine liver sections. White arrows show Ki67+ cells. n = 3. E, embryonic day. Scale bars: 100 µm (top row) and 10 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (G and H) Quantitation of proliferating Cdh5+ cells in control, KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre/+ (G), and BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre/+ (H) mutant murine livers. n = 3. Unpaired t test, P > 0.8. Two independent experiments. Data represent the mean ± SEM. N.S., not significant. BD, bile duct; LS, liver sinusoid; PV, portal vein.

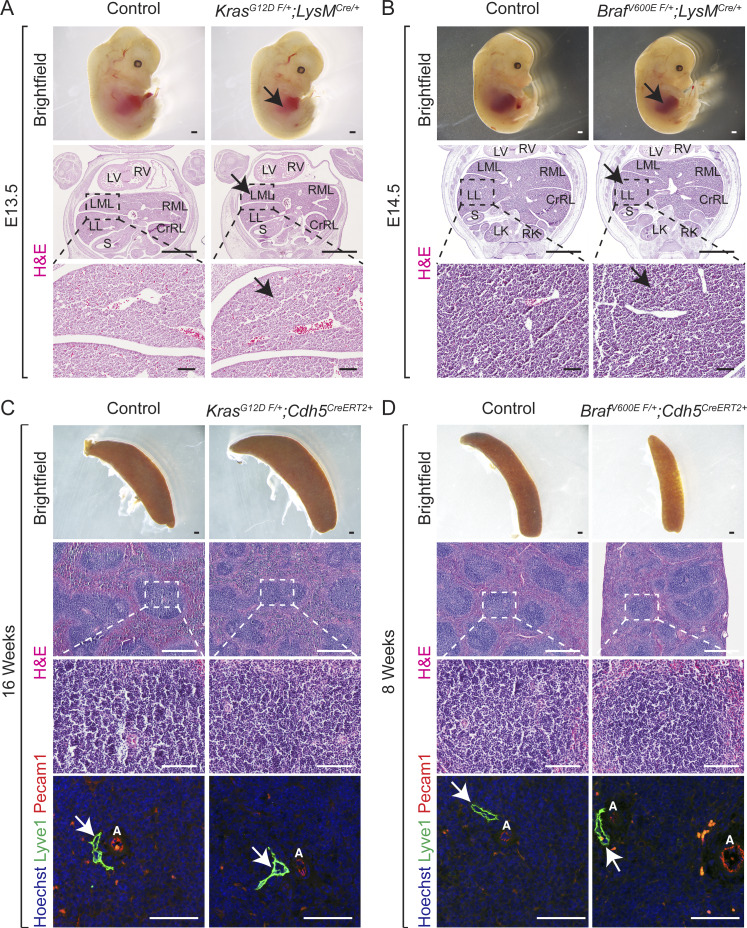

Figure S4.

Mice with KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations within macrophages exhibit normal normal sinusoidal and hepatic development. (A and B) Dissected KrasG12D F/+; LysMCre (A) and BrafV600E F/+; LysMCre (B) embryos show normal liver size (black arrows). H&E-stained KrasG12D F/+; LysMCre (A) and BrafV600E F/+; LysMCre (B) liver frontal sections show normal sinusoidal capillaries (black arrows). n = 3. E, embryonic day. Scale bars: 500 µm (top row), 1,000 µm (middle row), and 100 µm (bottom row). Two independent experiments. (C and D) Mice with KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations within endothelial cells exhibit normal normal spleen morphology and sinusoids. Spleen dissected from adult tamoxifen-treated KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) mice. H&E-stained KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) spleen sagittal sections show normal morphology. Lyve1 (green) and Pecam1 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (C) and BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2 (D) spleen sagittal sections. n = 3. Scale bars: 500 µm (first and second rows), 100 µm (third row), and 50 µm (fourth row). Two independent experiments. White arrows show normal Lyve1+ vessels. A, artery; CrRL, cranial right lobe; LK, left kidney; LL, left lobe; LML, left medial lobe; LV, left ventricle; RK, right kidney; RML, right medial lobe; RV, right ventricle; S, stomach.

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations aberrantly enhance “zipper-like” contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins at sinusoidal endothelial cell–cell contacts

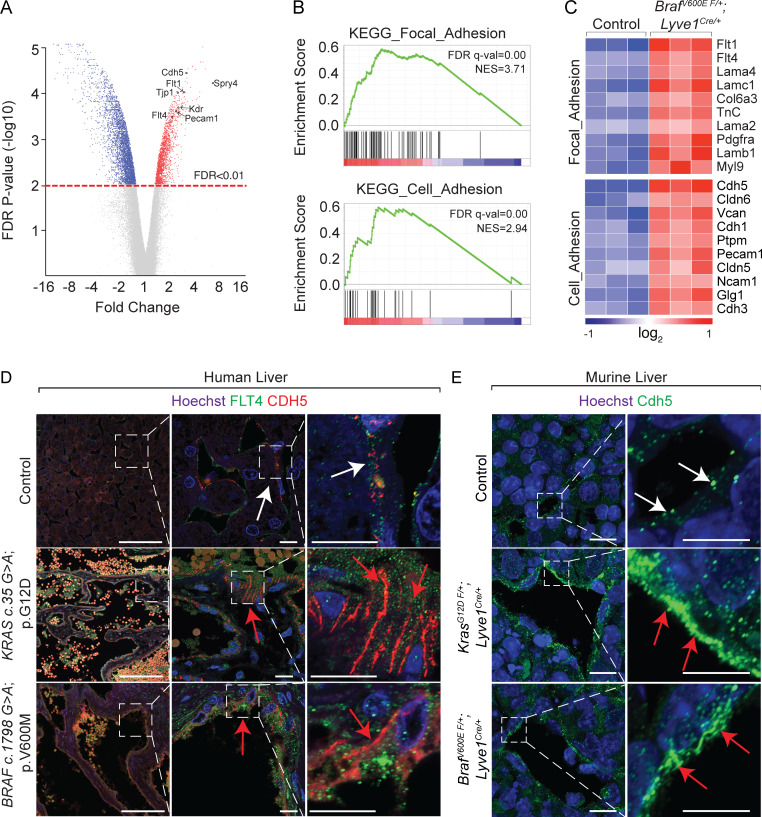

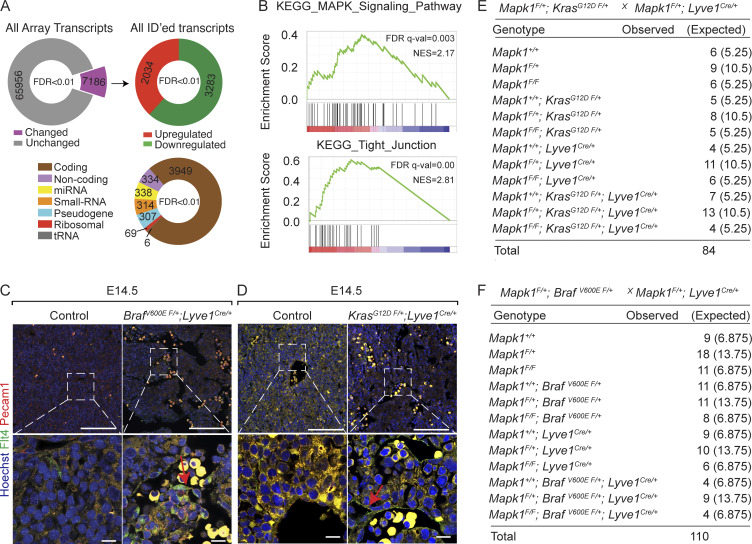

To define transcriptional changes, we performed an Affymetrix Clariom D assay on embryonic BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers (Fig. 3, A–C; and Fig. S5, A and B). Among 5,317 differentially regulated transcripts with National Center for Biotechnology Information identifiers, 62% were reduced, while 38% were increased in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre compared with control (Fig. 3, A–C; and Fig. S5 A). Gene set enrichment analysis showed enrichment in cell adhesion molecules, focal adhesion, tight junction, and MAPK signaling pathways (Fig. 3, A–C; and Fig. S5, A and B). These enriched categories contained almost exclusively up-regulated genes, suggesting that the BRAF gain-of-function mutation promotes endothelial cell–cell adhesion (Fig. 3, B and C). We observed a corresponding increase in protein expression of critical endothelial adherens junctional proteins Cdh5, Fms-related receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (Flt4), and Pecam1 and aberrant zipper-like contiguous expression pattern of Cdh5 in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre, KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre, BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2, KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2, and human hemangioma livers (Fig. 1 C; Fig. 3, D and E; Fig. S3, A, B, E, and F; and Fig. S5, C and D), suggesting abnormal contiguous adhesion between the hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations aberrantly enhance zipper-like contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins at sinusoidal endothelial cell–cell contacts. (A) Distribution of differentially up-regulated transcripts (red), down-regulated transcripts (blue), and unchanged transcripts (gray) in E11.5 BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers compared with littermate Control E11.5 livers (n = 3). FDR, false discovery rate. (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of differentially regulated, identified transcripts in E11.5 BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers (n = 3). (C) Heatmap of top differentially regulated transcripts within KEGG pathway categories of focal adhesion and cell adhesion (n = 3). (D and E) Flt4 and Cdh5 immunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on sections of human KRAS c.35 G>A (p.G12D) and BRAF c.1798G>A (p.V600M) liver (D) and Cdh5 immunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on murine KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre liver (E) and murine BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers (E). n = 3. White arrows show normal button-like discontiguous expression of junctional proteins between sinusoidal endothelial cells. Red arrows show abnormal zipper-like contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins at sinusoidal endothelial cell–cell contacts. Scale bars in D: 100 µm (first column from left) and 10 µm (second and third columns from left); scale bars in E: 10 µm (first column from left) and 5 µm (second column from left). All experimental data verified in at least two independent experiments.

Figure S5.

Endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations aberrantly enhance expression of adherens junctional proteins. (A) Analysis of differentially regulated transcripts show expression changes in E11.5 BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers (n = 3). (B) KEGG pathway gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of differentially regulated, identified transcripts in E11.5 BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre livers (n = 3). NES, normalized enriched score. (C and D) Flt4 (green) and Pecam1 (red) coimmunofluorescent staining with Hoechst nuclear counterstain (blue) on sections of murine BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryonic liver (C) and murine KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre liver (D). Red arrows show increased Flt4 expression. E, embryonic day. Scale bars: 100 µm (top row) and 10 µm (bottom row). n = 3. Two independent experiments. (E and F) Genotyping tables of embryos derived from Mapk1F/+; KrasG12D F/+ mice (E) or Mapk1F/+; BrafV600E F/+ (F) mice crossed with Mapk1F/+; Lyve1Cre/+ mice. χ2 P values 0.262 (E) and 0.991 (F).

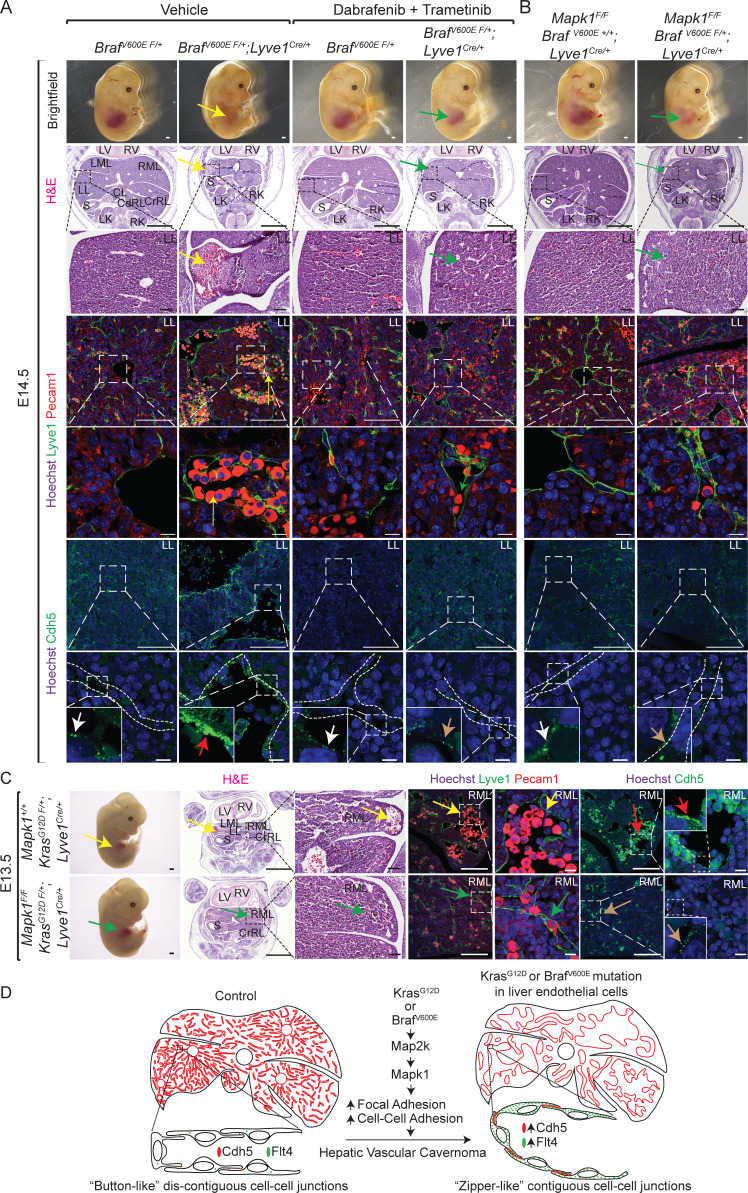

Pharmacological inhibition of BrafV600E-Map2k or genetic ablation of Mapk1 rescue hepatic vascular cavernomas in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre and KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre mice

Gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF hyperactivate the downstream canonical MAPK kinase (MAP2K)–MAPK signaling pathway in endothelial cells (Al-Olabi et al., 2018; Nikolaev et al., 2018). To investigate the requirement of Map2k hyperactivation in the pathogenesis of hepatic vascular cavernomas, we treated BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre murine embryos with pharmacological inhibitors of Map2k (trametinib) and BrafV600E (dabrafenib; Fig. 4 A). Inhibition of Map2k activity rescued hepatic vascular cavernomas, liver size, embryonic lethality, and aberrant zipper-like contiguous expression of sinusoidal endothelial cell adhesion proteins in developing BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre murine embryos (Fig. 4 A). Similarly, genetic ablation of endothelial Mapk1 prevented embryonic lethality, hepatic vascular cavernomas, and zipper-like contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre and KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre murine embryos (Fig. 4, B and C; and Fig. S5, E and F). Together, these results suggest that the hyperactivation of KRAS–BRAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway in sinusoidal endothelial cells enhances aberrant zipper-like cell–cell adhesion, promoting cavernous expansion of hepatic sinusoidal capillaries (Fig. 4 D).

Figure 4.

Pharmacologic inhibition of BrafV600E-Map2k or genetic ablation of Mapk1 rescue hepatic vascular cavernomas in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre and KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre mice. (A and B) Dissected BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre littermate embryos treated with dabrafenib and trametinib (A) or lacking Mapk1 (B) show rescued liver size (green arrows) compared with BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryos (yellow arrow; n = 3). H&E-stained or Lyve1 (green), Pecam1 (red), and Hoechst (blue) coimmunofluorescent–stained liver sections of BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre littermate embryos treated with dabrafenib and trametinib (A) or lacking Mapk1 (B) show normal sinusoidal capillaries (green arrows) compared with cavernous sinusoids in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryos (yellow arrows; n = 3). Immunofluorescent staining on liver sections of BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryos treated with dabrafenib and trametinib (A) or lacking Mapk1 (B) show normal button-like discontiguous expression of Cdh5 (brown arrows) compared with abnormal zipper-like contiguous expression of Cdh5 in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre embryos (red arrows; n = 3). White arrows show normal button-like discontiguous expression of Cdh5 in control livers. Scale bars: 500 µm (top row), 1,000 µm (second row from top), 100 µm (third, fourth, and sixth rows from top), and 10 µm (fifth and seventh rows from top). Two independent experiments. (C) Dissected KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre littermate embryos lacking Mapk1 show rescued liver size (green arrow), normal sinusoidal capillaries (green arrows) stained with H&E or Lyve1 (green) and Pecam1 (red), and normal button-like discontiguous expression of Cdh5 (brown arrows) compared with KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre (yellow and red arrows). n = 3. Scale bars: 500 µm (first column from left), 1,000 µm (second column from left), 100 µm (third, fourth, and sixth columns from left), and 10 µm (fifth and seventh columns from left). Two independent experiments. (D) Endothelial activating KRAS or BRAF mutations drive hepatic vascular cavernomas via MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway. Proposed model suggesting that constitutive activation of KRAS–BRAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway in sinusoidal endothelial cells promotes aberrant zipper-like contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins, such as Cdh5, switching hepatic sinusoidal capillaries from branching to cavernous expansion. All experimental data verified in at least two independent experiments. CdRL, caudal right lobe; CL, caudate lobe; CrRL, cranial right lobe; LK, left kidney; LL, left lobe; LML, left medial lobe; LV, left ventricle; RK, right kidney; RML, right medial lobe; RV, right ventricle; S, stomach.

Discussion

This study reveals the first and unexpected causal link between KRAS or BRAF mutations and hepatic vascular cavernomas. Mutations in RAS, the first human oncogene, and BRAF genes drive ∼30% of human tumors (Alcantara et al., 2019; Hunter et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2013; Der et al., 1982; Zhong et al., 1999; Davies et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2007), yet no reports describe RAS or RAF mutations in hepatic cavernous hemangiomas, the most common benign tumor of the liver. We identified somatic activating KRAS and/or BRAF mutations in human hepatic tissue samples with sporadic hemangioma lesion (Fig. 1, A and B; and Table 1). Low allele frequencies of KRAS and BRAF mosaic-activating mutations in these sporadic lesions are consistent with the cellular heterogeneity of vascular malformations (Nikolaev et al., 2018; Al-Olabi et al., 2018). This study is the first to model human hepatic cavernous vascular malformation in mice. Our murine models, for the first time, established that sinusoidal endothelial cells expressing gain-of-function KRASG12D or BRAFV600E mutations give rise to hepatic vascular cavernomas (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). This completely penetrant phenotype distinguishes KRASG12D and BRAFV600E as a somatic driver-mutations in slow-flow hepatic vascular cavernomas. In contrast, known genetic causes of human slow-flow malformations, such as germline mutations in KRIT1, CCM2, PDCD10, GLMN, RASA1, or TEK, may require a somatic “second hit” to drive vascular malformations (Macmurdo et al., 2016; Plummer et al., 2004; Vikkula et al., 1996).

Our study highlights a nononcogenic role of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E mutations in hepatic vascular cavernomas. These oncogenic forms of KRAS and BRAF drive tumorigenic growth of human cancer cells (Dankort et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2001). Here we demonstrate that KRASG12D or BRAFV600E mutations cause hepatic vascular cavernomas without modulating endothelial cell proliferation, suggesting a context-dependent role for KRAS and BRAF mutations in the sinusoidal endothelium (Fig. 1 C; Fig. S1, B and C; and Fig. S3). Consistent with this interpretation, somatic activating KRAS or BRAF mutations do not cause cancer in some tissues, such as brain, uterus, and spinal cord (Nikolaev et al., 2018; Al-Olabi et al., 2018). In addition, our study highlights overlapping phenotypic consequences of gain-of-function KRAS and BRAF mutations in hepatic vascular cavernomas. The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer reveals ∼99% mutation frequency in KRAS at three amino acids, G12 (∼89%), G13 (∼9%), and Q61 (∼1%). Among these mutations, G12D (∼36%) is the most prevalent, followed by G12C (∼14%), G12V (∼23%), and G13D (∼7%; Waters and Der, 2018; Prior et al., 2012). Similarly, V600 mutation represents ∼50% of all BRAF mutations in human tumors, with striking differences in replaced amino acids, i.e., V600E (∼70–90%), V600R (∼1%), V600M (∼0.3%), and V600D (∼0.1%; Pollock et al., 2003; Davies et al., 2002; Wan et al., 2004). Consistent with this, human hepatic tissue samples with sporadic hemangioma lesions revealed G12D, G12S, G13D, and/or G13S mutations in KRAS and/or V600M mutation in BRAF (Fig. 1, A and B; and Table 1). Despite these variations at hotspot amino acids G12/13 or V600, pathological human liver samples exhibited remarkable phenotypic resemblance, such as malformed sinusoidal capillary vessels, cavernous spaces filled with erythrocytes and lined by LYVE1+/CDH5+/PECAM1+ endothelial cells, and normal endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 1 C and Fig. S1, B and C). Consistent with the human phenotype, mice expressing KRASG12D or BRAFV600E in endothelial cells rapidly developed sinusoidal capillary dilation and hepatic vascular cavernomas without altering endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 2, Fig. S2, and Fig. S3). These data and previous literature reports suggest structural, biochemical, and functional similarities among KRAS G12/13 and BRAF V600 mutations (Yao et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2016; Hunter et al., 2015; Hobbs et al., 2016; Hobbs and Der, 2019). For example, KRAS G12D, G12C, and G12V mutations exhibit similar crystal structure and hyperactivate RAS, leading to sustained activation of the RAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway (Li et al., 2018; Muñoz-Maldonado et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2019; Ihle et al., 2012; Hobbs et al., 2016; Hunter et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2016). Similarly, both BRAF V600E and V600M mutations form homodimers in a RAS-dependent manner to activate the MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway (Yao et al., 2015; Pratilas et al., 2009; Rajakulendran et al., 2009). These structural and biochemical studies have supported the development of pharmacologic inhibitors directly targeting KRAS G12/13 mutations, BRAF V600 mutations, MAP2K, and MAPK1 in human tumors (Ostrem and Shokat, 2016; Shi et al., 2012; Waters and Der, 2018; Mullard, 2019; Cox et al., 2014; Samatar and Poulikakos, 2014; Ross et al., 2017).

Here we identify the RAS–RAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway as a critical regulator of the size, shape, and branching pattern of hepatic sinusoidal capillary vessels. The formation and maintenance of a 3D network of sinusoidal capillaries with fine adaptations in branching and vessel diameter is essential for liver growth and function (Géraud et al., 2017; Si-Tayeb et al., 2010). The endothelial lining of sinusoidal capillaries exhibits a unique morphology, with fenestrations grouped into sieve plates, specialized junctional complexes, and an incomplete basement membrane, facilitating transfer of solutes and large molecules between the bloodstream and hepatocytes. Sinusoidal endothelial cells exhibit a dynamic cellular rearrangement during sinusoid patterning and maintenance (Zapotoczny et al., 2019); however, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying hepatic vascular cavernomas remain unknown. In developing murine embryos, “button-like” discontiguous expression of adherens junctional complexes, comprising Pecam1, Cdh5, Vegfr2, and Flt4, between the endothelial cells drives the patterning and polarized cellular migration during vascular morphogenesis (Szymborska and Gerhardt, 2018; Bentley et al., 2014). Our data demonstrate that constitutive activation of the KRAS–BRAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway in sinusoidal endothelial cells promotes zipper-like contiguous expression of adherens junctional proteins, such as Cdh5, Pecam1, and Flt4, switching hepatic sinusoidal capillaries from branching to cavernous expansion (Fig. 4 D). Our findings support a model in which discontiguous adhesion drives intercalation, and thus sinusoidal capillary branching, whereas contiguous adhesion disrupts intercalation, and thereby expansion of sinusoidal capillary diameter (Fig. 4 D). These data support prior observations that Pecam1, Cdh5, Flt4, and Vegfr2 complex, classically associated with endothelial cell proliferation, regulates integrity of endothelial cell–cell junctions (Tzima et al., 2005; Privratsky and Newman, 2014; Lampugnani et al., 2018; Dejana and Vestweber, 2013; Coon et al., 2015). For example, Pecam1 interacts with Cdh5 at endothelial cell–cell contacts to regulate junctional integrity and movement of endothelial cells (Privratsky and Newman, 2014; Tzima et al., 2005). Mice lacking Cdh5 exhibit embryonic lethality owing to defective Vegfr signaling and endothelial cell–cell interactions, suggesting a functional relationship between these receptors (Carmeliet et al., 1999). Consistent with this interpretation, mice with loss of Flt4 function show defective integrity of endothelial cell–cell junctions due to reduced junctional Cdh5 localization and increased Vegfr2 expression (Heinolainen et al., 2017; Tammela et al., 2008). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that activity of Flt4 and Vegfr2 is essential for Pecam1-Cdh5 adherens junction integrity at endothelial cell–cell contacts.

This is the first report, to our knowledge, of an effective molecular therapy for hepatic vascular cavernomas in mice. KRASG12D or BRAFV600E mutations drive constitutive activation of the classic MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway (Dankort et al., 2007; Van Meter et al., 2007). Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs dabrafenib and trametinib inhibit BRAFV600E and MAP2K, respectively (Ribas and Flaherty, 2011), two kinases within the RAS–RAF–MAP2K–MAPK1 signaling pathway. In our murine models, concurrent administration of dabrafenib and trametinib inhibited the growth of BRAFV600E-dependent hepatic vascular cavernomas (Fig. 4 A). This is consistent with recent randomized, multicenter clinical trials (NCT01584648 and NCT01597908) demonstrating that dabrafenib plus trametinib improve progression-free survival and overall survival of patients with BRAFV600E-positive tumors (Robert et al., 2019). The present study takes this therapeutic approach one step further by revealing that Mapk1 functions as a critical downstream factor to promote KrasG12D- or BrafV600E-dependent hepatic vascular cavernomas. Genetic ablation of Mapk1 in BrafV600E F/+; Lyve1Cre and KrasG12D F/+; Lyve1Cre mice rescued the hepatic vascular cavernomas phenotype, suggesting Mapk1 as a novel therapeutic target (Fig. 4, B and C). Together, our murine models provide a platform to test novel pharmacological compounds to prevent formation and enlargement of RAS–MAPK1 signaling pathway–dependent hepatic vascular cavernomas.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

A total of 43 patients were initially included in the study after searching the database covering a period of 10 yr for diagnostic keywords “liver hemangioma.” For comparison, initially included as controls were a total of 10 patients whose liver tissue specimens were available in the tissue archive for non–vascular-related pathology and did not have known KRAS- or BRAF-driven cancer pathology. Tissue blocks containing liver hemangioma lesions and blocks containing liver from controls were retrieved, and a trained pathologist reviewed H&E-stained sections from the blocks. Patient liver specimens (n = 4) that did not contain hemangioma lesions or control liver samples affected with marked cirrhosis/fibrosis were excluded from further analysis. Review of clinical and pathological information and study of archived tissue samples were approved with waiver for informed consent (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver) by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board. Because of the large number of subjects and the time frame and retrospective nature of the study, the research could not practicably be performed without the waiver of informed consent. Patient data and specimens with or without preexisting pathology were collected for clinical reasons as per the Institutional Review Board approval. A data collection sheet was used to record data using a deidentified, separate numbering system. The data, including slides, were deidentified and given a separate number. The deidentified data are stored in locked investigator offices and password protected, with access to only authorized study personnel.

DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue

Sections of FFPE tissue blocks from patients and controls were used for DNA extraction; where necessary, patient sections were microdissected to improve lesion coverage. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized by sequential washes in xylene and 100% ethanol. Samples were then centrifuged, air-dried, and incubated overnight in tissue lysis buffer and proteinase K. Finally, samples were loaded in QIAcube as per the instructions in the instrument manual, and DNA was eluted into the buffer provided with the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit. Eluted DNA was quantified using nanodrop, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until downstream analyses.

Next-generation sequencing

Next-generation sequencing was performed as previously described (Kamionek et al., 2016). 37 primer pairs were used to cover the known hotspot mutations in KRAS, NRAS, HRAS (codons 12, 13, 61, and 146), BRAF (codons 460–470 and 600), and the entire coding sequence of the MAP2K1 gene. For the purposes of the current study, only mutations in the hotspot codons of KRAS (codons 12 and 13) and BRAF (codon 600) were further analyzed in depth. Amplicon libraries were created from genomic DNA (10 ng), according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The Ion CHEF Template System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for emulsion PCR to amplify library DNA onto IonSphere Particles and loaded on 318v2 chips. Sequencing was performed on an Ion Torrent PGM (IC200 Sequencing Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with coverage of ×5,000 to ×10,000. Raw sequencing data files were analyzed using two pipelines, Variant Caller (Life Technologies) and NextGene (SoftGenetics), and output was compared using a laboratory-developed visual basic Excel program. Variants with an allele frequency >0.1% detected at the hotspot codons of KRAS and BRAF from either pipeline were called positive. Further, all positive calls were manually verified using NextGene (SoftGenetics) alignment viewer.

Mutational analysis by PCR clamp assay and Sanger sequencing

KRAS codon 12/13 or BRAF codon 600 was analyzed using BNA clamp real-time quantitative PCR, and specific primer sets (IDT) were used (BRAF-F, 5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTAAACTCTTCATAATGCTTGCTCTG-3′, BRAF-R, 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACGGACCCACTCCATCGAGA-3′; KRAS-F, 5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGTACTGGTGGAGTATTTGATAGTG-3′; and KRAS-R, 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACATCGTCAAGGCACTCTTGCCTAC-3′). M13F or M13R sequencing primers are underlined. SsoFast Evagreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) and DNA in a total volume of 20 µl were used with or without a BNA clamp (BRAF BNA, 5′-GATTTCACTGTAGC-spacerC3-3′, and KRAS BNA, 5′-mUA+CGCCACCAGCT-spacerC3-3′; BioSynthesis). A Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time thermal cycler was used. The PCR conditions were as follows: 98°C denaturation for 2 min, then 60 cycles of 60°C for 5 s, and 98°C for 5 s. Briefly, real-time quantitative PCR was performed with and without a BNA clamp designed to block amplification of wild-type sequences. The delta threshold count (ΔCT) was calculated from the difference between the Ct values obtained from PCR performed without clamp and with clamp. The RKO human colon cell line, with c. 1799T>A (p.V600E) BRAF mutation, was used as positive control (ATCC). Specimens with a ΔCT ≥ the negative control were deemed K-RAS and/or BRAF wild type. The remaining specimens were regarded as positive, and mutation status was confirmed by BigDye Sanger methodology (Life Technologies) using capillary gel electrophoresis (ABI 3500xL). Results were interpreted using Mutation Surveyor V4.0.8 (SoftGenetics). This assay detects all known mutations in KRAS codons 12/13 and between BRAF codons 598 and 602 with a detection limit of <0.1%.

Mice

KrasG12D, BRAFV600E, Mapk1Flox, Lyve1Cre, LysMCre, and Gt(ROSA)26Sor-LacZ reporter mice and Cdh5CreERT2 have been described previously (Clausen et al., 1999; Dankort et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2001; Pham et al., 2010; Samuels et al., 2008; Sörensen et al., 2009; Soriano, 1999). All mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background. Mice were backcrossed for at least five generations to reference strains, and littermates were used as controls for all experiments. Neonatal mice were administered tamoxifen once daily orally on postnatal days 0, 1, and 2 or postnatal days 3, 4, and 5 at a dose of 50 µg/d, and all mice were analyzed at postnatal day 12. Adult mice were treated with tamoxifen once daily for 3 d consecutively at 6 wk of age with a dose of 1 mg/10 g body weight, and mice were euthanized at 16 wk (KrasG12D F/+; Cdh5CreERT2/+) or 8–9 wk (BrafV600E F/+; Cdh5CreERT2/+) of age for tissue analyses. For pharmacologic rescue experiments, pregnant mice were treated once daily by oral gavage with either vehicle (0.2% Tween 80 and 0.5% hydroxymethyl cellulose dissolved in water) or trametinib (0.5 µg/g body weight/d) and dabrafenib (25 µg/g body weight/d) dissolved in vehicle solution for 5 consecutive days from embryonic days 9.5 to 13.5. University of Massachusetts Medical School is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and follows the Public Health Service Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 2011). University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Worcester, MA) approved all animal use protocols.

Histology

Murine embryos and tissues were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, ethanol dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 8-µm thickness using a Leica fully motorized rotary microtome. FFPE tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through an ethanol gradient, followed by 2-min Harris-modified hematoxylin and 30-s eosin-Y staining. Slides were dehydrated with ethanol, cleared with xylene, and mounted with Vectashield glass mounting medium.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Janardhan et al., 2017). Briefly, slides with sections were deparaffinized and immersed in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate and 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6) and placed in a 2100 Antigen Retriever (Aptum Biologics) for heat-induced antigen retrieval. After antigen retrieval, sections were blocked in 10% donkey serum, 0.1% BSA, and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then washed in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies (Table S1) in 10% donkey serum and PBS overnight at 4°C. Finally, slides were washed in PBS, incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 or 546/568 conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500) with Hoechst (1:1,000) for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed in PBS, and mounted with Vectashield glass mounting medium.

Imaging

Images of dissected embryos, mice, and tissue samples were captured using a Leica MZ10 F fluorescence stereomicroscope equipped with a 0.7× C-mount, Achromat 1.0 × 90-mm objective, a SOLA light engine, a DS-Fi1 color camera (Nikon), and NIS-Elements Basic Research software (Nikon). H&E-stained section images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with CFI Plan Fluor 4×/10×/20×/40× objective lenses, a DS-Fi1 color camera, and NIS-Elements Basic Research software. Immunofluorescent-stained slides were imaged using Plan-Apochromat objectives with DIC (63×/1.4 oil, and 20×/0.8) on Zeiss LSM800 Airyscan inverted digital spectral confocal microscope equipped with Definite Focus 2.0, three confocal GaAsP detectors including Airyscan detector with 6,000 × 6,000-pixel resolution, and solid-state laser module with 405-, 488-, 561-, and 640-nm beam splitter. Image stacks of vertical projections were assembled using Zeiss Zen 2.5 imaging software.

Microarray

Livers from embryonic day 11.5 embryos were dissected, cleared of blood, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further processing. After genotyping, eight liver samples each from control and mutant embryos were respectively pooled before RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNAeasy microkit as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted RNA was then aliquoted into three tubes each for control and mutants. All samples were checked for quality using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and had an RNA integrity number >9.5. Microarray analysis was performed by the University of Massachusetts Genomics Core Facility using Mouse Clariom D array (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Raw microarray .cel files were imported and processed using Transcriptome Analysis Console version 4.0. Full microarray datasets can be accessed at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession no. GSE147848.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined based on a two-tailed Student’s t test or χ2 test (GraphPad Prism 8.0). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows hepatic vascular cavernomas with normal endothelial cell proliferation in human patients with somatic gain-of-function mutations in KRAS or BRAF genes. Fig. S2 shows hepatic vascular cavernomas and embryonic lethality in mice with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations. Fig. S3 shows normal proliferation of hepatic endothelial cells in mice with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations. Fig. S4 shows normal sinusoidal and hepatic development in mice with macrophage KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations. In addition, mice with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations show normal spleen morphology and sinusoids. Fig. S5 shows increased expression of adherens junctional proteins in mice with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations. In addition, genetic ablation of endothelial Mapk1 rescues lethality at embryonic day 14.5 in embryos with endothelial KrasG12D or BrafV600E gain-of-function mutations. Table S1 lists the antibodies used.

Supplementary Material

lists the antibodies used.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Benjamin Chen, MD, PhD (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) for his help with examination of hemangioma patient samples. We thank the University of Massachusetts Medical School Genomics Core Facility for help with the microarray experiment.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL141377 (to C.M. Trivedi).

Author contributions: H.P. Janardhan and C.M. Trivedi conceived the study, designed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. H.P. Janardhan, X. Meng, K. Dresser, L. Hutchinson, and C.M. Trivedi performed experiments and acquired and analyzed data. All authors reviewed results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Al-Olabi L., Polubothu S., Dowsett K., Andrews K.A., Stadnik P., Joseph A.P., Knox R., Pittman A., Clark G., Baird W., et al. . 2018. Mosaic RAS/MAPK variants cause sporadic vascular malformations which respond to targeted therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 128:1496–1508. 10.1172/JCI98589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara K.M.M., Malapit J.R.P., Yu R.T.D., Garrido J.A.M.G., Rigor J.P.T., Angeles A.K.J., Cutiongco-de la Paz E.M., and Garcia R.L.. 2019. Non-Redundant and Overlapping Oncogenic Readouts of Non-Canonical and Novel Colorectal Cancer KRAS and NRAS Mutants. Cells. 8:1557 10.3390/cells8121557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K., Franco C.A., Philippides A., Blanco R., Dierkes M., Gebala V., Stanchi F., Jones M., Aspalter I.M., Cagna G., et al. . 2014. The role of differential VE-cadherin dynamics in cell rearrangement during angiogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16:309–321. 10.1038/ncb2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Lampugnani M.G., Moons L., Breviario F., Compernolle V., Bono F., Balconi G., Spagnuolo R., Oosthuyse B., Dewerchin M., et al. . 1999. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 98:147–157. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81010-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen B.E., Burkhardt C., Reith W., Renkawitz R., and Förster I.. 1999. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 8:265–277. 10.1023/A:1008942828960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon B.G., Baeyens N., Han J., Budatha M., Ross T.D., Fang J.S., Yun S., Thomas J.-L., and Schwartz M.A.. 2015. Intramembrane binding of VE-cadherin to VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 assembles the endothelial mechanosensory complex. J. Cell Biol. 208:975–986. 10.1083/jcb.201408103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox A.D., Fesik S.W., Kimmelman A.C., Luo J., and Der C.J.. 2014. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13:828–851. 10.1038/nrd4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankort D., Filenova E., Collado M., Serrano M., Jones K., and McMahon M.. 2007. A new mouse model to explore the initiation, progression, and therapy of BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors. Genes Dev. 21:379–384. 10.1101/gad.1516407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H., Bignell G.R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., Teague J., Woffendin H., Garnett M.J., Bottomley W., et al. . 2002. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 417:949–954. 10.1038/nature00766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejana E., and Vestweber D.. 2013. The role of VE-cadherin in vascular morphogenesis and permeability control. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 116:119–144. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394311-8.00006-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der C.J., Krontiris T.G., and Cooper G.M.. 1982. Transforming genes of human bladder and lung carcinoma cell lines are homologous to the ras genes of Harvey and Kirsten sarcoma viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:3637–3640. 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerichs F.T. 1860. A clinical treatise on diseases of the liver. New Sydenham Society: London; 1010 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Géraud C., Koch P.-S., Zierow J., Klapproth K., Busch K., Olsavszky V., Leibing T., Demory A., Ulbrich F., Diett M., et al. . 2017. GATA4-dependent organ-specific endothelial differentiation controls liver development and embryonic hematopoiesis. J. Clin. Invest. 127:1099–1114. 10.1172/JCI90086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graivier L., Votteler T.P., and Dorman G.W.. 1967. Hepatic hemangiomas in newborn infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2:299–307. 10.1016/S0022-3468(67)80208-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton F.E., and Holmes R.H.. 1950. Cavernous hemangioma of the left lobe of the liver; report of a case. U. S. Armed Forces Med. J. 1:443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinolainen K., Karaman S., D’Amico G., Tammela T., Sormunen R., Eklund L., Alitalo K., and Zarkada G.. 2017. VEGFR3 Modulates Vascular Permeability by Controlling VEGF/VEGFR2 Signaling. Circ. Res. 120:1414–1425. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J.G. 1948. Hemangioma of the liver causing death in a newborn infant. J. Pediatr. 32:309–310. 10.1016/S0022-3476(48)80038-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G.A., and Der C.J.. 2019. RAS Mutations Are Not Created Equal. Cancer Discov. 9:696–698. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G.A., Der C.J., and Rossman K.L.. 2016. RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 129:1287–1292. 10.1242/jcs.182873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J.C., Manandhar A., Carrasco M.A., Gurbani D., Gondi S., and Westover K.D.. 2015. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of Common Cancer-Associated KRAS Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 13:1325–1335. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle N.T., Byers L.A., Kim E.S., Saintigny P., Lee J.J., Blumenschein G.R., Tsao A., Liu S., Larsen J.E., Wang J., et al. . 2012. Effect of KRAS oncogene substitutions on protein behavior: implications for signaling and clinical outcome. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104:228–239. 10.1093/jnci/djr523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson E.L., Willis N., Mercer K., Bronson R.T., Crowley D., Montoya R., Jacks T., and Tuveson D.A.. 2001. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 15:3243–3248. 10.1101/gad.943001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janardhan H.P., Milstone Z.J., Shin M., Lawson N.D., Keaney J.F. Jr., and Trivedi C.M.. 2017. Hdac3 regulates lymphovenous and lymphatic valve formation. J. Clin. Invest. 127:4193–4206. 10.1172/JCI92852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.W., Lin Y.-J., Reid D., Parker J., Pavlopoulos S., Dischinger P., Graveel C., Aguirre A.J., Steensma M., Haigis K.M., et al. . 2019. Isoform-Specific Destabilization of the Active Site Reveals a Molecular Mechanism of Intrinsic Activation of KRas G13D. Cell Rep. 28:1538–1550.e7. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamionek M., Ahmadi Moghaddam P., Sakhdari A., Kovach A.E., Welch M., Meng X., Dresser K., Tomaszewicz K., Cosar E.F., Mark E.J., et al. . 2016. Mutually exclusive extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway mutations are present in different stages of multi-focal pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis supporting clonal nature of the disease. Histopathology. 69:499–509. 10.1111/his.12955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampugnani M.G., Dejana E., and Giampietro C.. 2018. Vascular Endothelial (VE)-Cadherin, Endothelial Adherens Junctions, and Vascular Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10 a029322 10.1101/cshperspect.a029322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Balmain A., and Counter C.M.. 2018. A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: finding the sweet spot. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 18:767–777. 10.1038/s41568-018-0076-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Jang H., Nussinov R., and Zhang J.. 2016. The Structural Basis of Oncogenic Mutations G12, G13 and Q61 in Small GTPase K-Ras4B. Sci. Rep. 6:21949 10.1038/srep21949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmurdo C.F., Wooderchak-Donahue W., Bayrak-Toydemir P., Le J., Wallenstein M.B., Milla C., Teng J.M.C., Bernstein J.A., and Stevenson D.A.. 2016. RASA1 somatic mutation and variable expressivity in capillary malformation/arteriovenous malformation (CM/AVM) syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 170:1450–1454. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullard A. 2019. Cracking KRAS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18:887–891. 10.1038/d41573-019-00195-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Maldonado C., Zimmer Y., and Medová M.. 2019. A Comparative Analysis of Individual RAS Mutations in Cancer Biology. Front. Oncol. 9:1088 10.3389/fonc.2019.01088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev S.I., Vetiska S., Bonilla X., Boudreau E., Jauhiainen S., Rezai Jahromi B., Khyzha N., DiStefano P.V., Suutarinen S., Kiehl T.-R., et al. . 2018. Somatic Activating KRAS Mutations in Arteriovenous Malformations of the Brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 378:250–261. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J.M.L., and Shokat K.M.. 2016. Direct small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: from structural insights to mechanism-based design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15:771–785. 10.1038/nrd.2016.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T.H.M., Baluk P., Xu Y., Grigorova I., Bankovich A.J., Pappu R., Coughlin S.R., McDonald D.M., Schwab S.R., and Cyster J.G.. 2010. Lymphatic endothelial cell sphingosine kinase activity is required for lymphocyte egress and lymphatic patterning. J. Exp. Med. 207:17–27. 10.1084/jem.20091619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer N.W., Gallione C.J., Srinivasan S., Zawistowski J.S., Louis D.N., and Marchuk D.A.. 2004. Loss of p53 sensitizes mice with a mutation in Ccm1 (KRIT1) to development of cerebral vascular malformations. Am. J. Pathol. 165:1509–1518. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63409-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock P.M., Harper U.L., Hansen K.S., Yudt L.M., Stark M., Robbins C.M., Moses T.Y., Hostetter G., Wagner U., Kakareka J., et al. . 2003. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat. Genet. 33:19–20. 10.1038/ng1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratilas C.A., Taylor B.S., Ye Q., Viale A., Sander C., Solit D.B., and Rosen N.. 2009. (V600E)BRAF is associated with disabled feedback inhibition of RAF-MEK signaling and elevated transcriptional output of the pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:4519–4524. 10.1073/pnas.0900780106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior I.A., Lewis P.D., and Mattos C.. 2012. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 72:2457–2467. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privratsky J.R., and Newman P.J.. 2014. PECAM-1: regulator of endothelial junctional integrity. Cell Tissue Res. 355:607–619. 10.1007/s00441-013-1779-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakulendran T., Sahmi M., Lefrançois M., Sicheri F., and Therrien M.. 2009. A dimerization-dependent mechanism drives RAF catalytic activation. Nature. 461:542–545. 10.1038/nature08314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas A., and Flaherty K.T.. 2011. BRAF targeted therapy changes the treatment paradigm in melanoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8:426–433. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro M.A. Jr., Papaiordanou F., Gonçalves J.M., and Chaib E.. 2010. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangiomas: A review of the literature. World J. Hepatol. 2:428–433. 10.4254/wjh.v2.i12.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C., Grob J.J., Stroyakovskiy D., Karaszewska B., Hauschild A., Levchenko E., Chiarion Sileni V., Schachter J., Garbe C., Bondarenko I., et al. . 2019. Five-Year Outcomes with Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Metastatic Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 381:626–636. 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S.J., Revenko A.S., Hanson L.L., Ellston R., Staniszewska A., Whalley N., Pandey S.K., Revill M., Rooney C., Buckett L.K., et al. . 2017. Targeting KRAS-dependent tumors with AZD4785, a high-affinity therapeutic antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of KRAS. Sci. Transl. Med. 9 eaal5253 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samatar A.A., and Poulikakos P.I.. 2014. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13:928–942. 10.1038/nrd4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels I.S., Karlo J.C., Faruzzi A.N., Pickering K., Herrup K., Sweatt J.D., Saitta S.C., and Landreth G.E.. 2008. Deletion of ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase identifies its key roles in cortical neurogenesis and cognitive function. J. Neurosci. 28:6983–6995. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0679-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Moriceau G., Kong X., Lee M.-K., Lee H., Koya R.C., Ng C., Chodon T., Scolyer R.A., Dahlman K.B., et al. . 2012. Melanoma whole-exome sequencing identifies (V600E)B-RAF amplification-mediated acquired B-RAF inhibitor resistance. Nat. Commun. 3:724 10.1038/ncomms1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si-Tayeb K., Lemaigre F.P., and Duncan S.A.. 2010. Organogenesis and development of the liver. Dev. Cell. 18:175–189. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.J., Neel B.G., and Ikura M.. 2013. NMR-based functional profiling of RASopathies and oncogenic RAS mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:4574–4579. 10.1073/pnas.1218173110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen I., Adams R.H., and Gossler A.. 2009. DLL1-mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood. 113:5680–5688. 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. 1999. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 21:70–71. 10.1038/5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymborska A., and Gerhardt H.. 2018. Hold Me, but Not Too Tight-Endothelial Cell-Cell Junctions in Angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10 a029223-18 10.1101/cshperspect.a029223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait N., Richardson A.J., Muguti G., and Little J.M.. 1992. Hepatic cavernous haemangioma: a 10 year review. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 62:521–524. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T., Zarkada G., Wallgard E., Murtomäki A., Suchting S., Wirzenius M., Waltari M., Hellström M., Schomber T., Peltonen R., et al. . 2008. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature. 454:656–660. 10.1038/nature07083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R.K., Baker A.C., Debiasi R.M., Winckler W., Laframboise T., Lin W.M., Wang M., Feng W., Zander T., MacConaill L., et al. . 2007. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat. Genet. 39:347–351. 10.1038/ng1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E., Irani-Tehrani M., Kiosses W.B., Dejana E., Schultz D.A., Engelhardt B., Cao G., DeLisser H., and Schwartz M.A.. 2005. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 437:426–431. 10.1038/nature03952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter M.E.M., Díaz-Flores E., Archard J.A., Passegué E., Irish J.M., Kotecha N., Nolan G.P., Shannon K., and Braun B.S.. 2007. K-RasG12D expression induces hyperproliferation and aberrant signaling in primary hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 109:3945–3952. 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikkula M., Boon L.M., Carraway K.L. III, Calvert J.T., Diamonti A.J., Goumnerov B., Pasyk K.A., Marchuk D.A., Warman M.L., Cantley L.C., et al. . 1996. Vascular dysmorphogenesis caused by an activating mutation in the receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2. Cell. 87:1181–1190. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81814-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virchow R. 1863. Angiome. In: Die krankhaften Geschwülste. Verlag von August Hirschwald: Berlin; 600 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Wan P.T.C., Garnett M.J., Roe S.M., Lee S., Niculescu-Duvaz D., Good V.M., Jones C.M., Marshall C.J., Springer C.J., Barford D., et al. ; Cancer Genome Project . 2004. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 116:855–867. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00215-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters A.M., and Der C.J.. 2018. KRAS: The Critical Driver and Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8 a031435 10.1101/cshperspect.a031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Torres N.M., Tao A., Gao Y., Luo L., Li Q., de Stanchina E., Abdel-Wahab O., Solit D.B., Poulikakos P.I., et al. . 2015. BRAF Mutants Evade ERK-Dependent Feedback by Different Mechanisms that Determine Their Sensitivity to Pharmacologic Inhibition. Cancer Cell. 28:370–383. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapotoczny B., Szafranska K., Kus E., Braet F., Wisse E., Chlopicki S., and Szymonski M.. 2019. Tracking Fenestrae Dynamics in Live Murine Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells. Hepatology. 69:876–888. 10.1002/hep.30232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Delva L., Rachez C., Cenciarelli C., Gandini D., Zhang H., Kalantry S., Freedman L.P., and Pandolfi P.P.. 1999. A RA-dependent, tumour-growth suppressive transcription complex is the target of the PML-RARalpha and T18 oncoproteins. Nat. Genet. 23:287–295. 10.1038/15463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

lists the antibodies used.