Abstract

A number of countries are planning the use of “immunity passports” as a way to ease restrictive measures and allow infected and recovered people to return to work during the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper brings together key scientific uncertainties regarding the use of serological tests to assure immune status and a public health ethics perspective to inform key considerations in the ethical implementation of immunity passport policies. Ill-conceived policies have the potential to cause severe unintended harms that could result in greater inequity, the stigmatization of certain sectors of society, and heightened risks and unequal treatment of individuals due to erroneous test results. Immunity passports could, however, be used to achieve collective benefits and benefits for specific populations besides facilitating economic recovery. We conclude that sector-based policies that prioritize access to testing based on societal need are likely to be fairer and logistically more feasible, while minimizing stigma and reducing incentives for fraud. Clear guidelines need to be set out for which sectors of society should be prioritized for testing, and rigorous mechanisms should be in place to validate test results and identify cases of reinfection.

Keywords: ethics, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, serological assays, disease control policy, equity, stigma, immunity passports

Ethical implementation of COVID-19 immunity passport policies should address concerns of equity, stigma, and unintended harms. Centralized, sector-based policies, prioritizing access to testing based on societal need, are likely fairer and logistically more feasible, minimizing stigma and reducing fraud.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in severe movement restrictions in many countries. These come at tremendous social cost, and there are ethical and economic imperatives to use proportionate strategies that minimize the duration of disruption. A key challenge is that social distancing measures can keep transmission in check but, without widely available vaccines, easing restrictions risks surges in transmission. This will occur until a sufficient fraction of the population has been infected and developed immunity, such that epidemics can no longer be sustained.

“Immunity passports” or certificates have been proposed to ease restrictions on infected and recovered individuals, allowing some people to return to work and kick-start economic recovery. These passports would rely on verifying an individual’s serological status using tests to detect antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Such tests are increasingly widely available, but key scientific questions remain. Specifically, the correlation between presence of antibodies and immunological protection, and the duration of immunity to SARS-CoV-2, are unclear. Additionally, the lag between infection and antibody development can affect test accuracy, as infected individuals may test negative if testing is done before antibodies develop. Based on these scientific considerations, the World Health Organization (WHO) currently does not support the use of immunity passports but will review their guidance as the evidence evolves [1].

Besides these scientific challenges, implementation of immunity passport policies raises important ethical questions [2]. Here, we use a public health ethics framework to examine ethical implications of immunity passport policies. A central public health ethics principle is that of least restrictive intervention, which requires policy makers to choose measures that would least interfere with the valuable freedoms of individuals to achieve public health objectives [3]. If scientifically supported, allowing individuals who are immune and pose little risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to regain their liberties through immunity certification satisfies this principle [4]. While immunity passports could lead to unequal liberties and privileges between immune-certified and noncertified individuals, this is not inherently discriminatory if founded on evidence-based risk stratification [4, 5]. These arguments provide in-principle support for immunity passport policies. However, the acceptability of such policies depends on mitigating ethical concerns related to their implementation. Here, we examine ethical concerns related to equity, stigma, and unintended harms, highlight some potential benefits of immunity passport policies, and make recommendations for their ethical implementation from a public health perspective.

EQUITY

Even if serological tests deployable en masse become available, supplies will initially be limited; prioritizing access to testing is a key consideration. Crucially, equity principles do not imply equal access, but require needs assessment. Globally, more vulnerable economies should be prioritized over more resilient ones. Nationally, needs also vary substantially and should inform prioritization. Workers in certain sectors are needed more urgently, including emergency services personnel, law enforcement, and teachers. Others, including health care and social workers, have contact with more vulnerable populations. Social distancing measures also impact certain groups more severely, including those with limited mobility who rely on services provided by others.

Financial barriers to testing should also be considered. Globally, allowing market forces to dictate access will exacerbate inequities, allowing wealthier countries that can afford mass testing to recover sooner without assured access to testing for low-income countries. Pooling of funds from international agencies and public-private partnerships should be considered to help finance testing in low-income countries.

At the individual level, if cost is a barrier to testing, those needing to return to work more urgently, such as day-wage earners, migrant laborers, low-income families, and those who cannot work while in isolation may be less able to pay for testing that could allow them to resume work. If the implementation of social distancing measures, and the mitigation of their impacts, is a state responsibility, then the cost of testing for immunity certification should be borne by the state, either directly or through employer-based financing schemes.

STIGMA

Classifying certain individuals as fit for work based on immunological status could result in stigma from inability to resume normal activities, and create resentment at the stratification of society according to “immunological fitness.” Ironically, here stigma could be associated with people who have yet to be infected. In certain settings, such as schools, such stigma could be amplified, contributing to disparities in mental and physical health, and access to education. Public health measures that result in stigma are not inherently unethical insofar as stigma is not an intended effect to achieve the public good [6]. Nevertheless, policy makers are obligated to ensure that any stigma resulting from immunity passports is mitigated and short term. In this regard, immunity passport policies should be recognized and communicated as stop-gap measures within wider, multipronged approaches to help society transition out of restrictive measures, until effective vaccines become widely available.

UNINTENDED HARMS

The ability to return to work sooner may provide perverse incentives to deliberately increase one’s SARS-CoV-2 exposure. Such behavior is highly undesirable, given the known risk of severe illness and the current strain on scarce intensive care resources in most countries.

Another concern is the potential for fraud through falsified blood samples or test results, which could enable susceptible individuals to resume normal activities, thus posing an increased infection risk to themselves and others. Such behaviors run counter to a general duty not to harm others and the heavy emphasis in many countries on collective responsibility and cooperation with public health measures to protect others. Similar perverse incentives have been reported from countries that require proof of a negative test of active SARS-CoV-2 infection from individuals travelling between regions; in some countries this has led to a black market for counterfeit certificates [7]. Such fraud could be mitigated through digital verification systems. For example, blockchain applications are in development to link verified test results with individual identity [8]. Such technologies, however, require public trust in mechanisms for privacy protection, and legal and regulatory mechanisms will be needed to limit access to and abuses of such data.

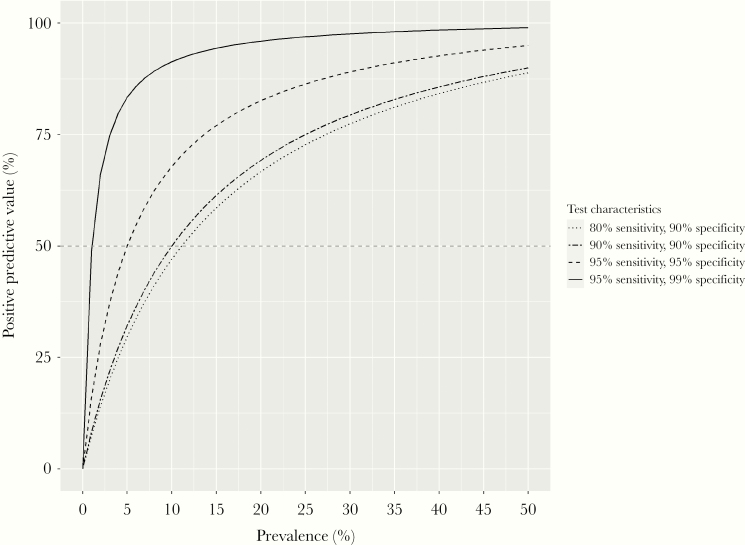

Aside from fraud, inappropriate easing of restrictions for some individuals could occur simply because of limitations on the predictive ability of serological tests. Ideally tests should minimize false positives (which would allow susceptible individuals to return to work) and false negatives (which would deny recovered individuals the chance to return to work sooner). Of particular interest here is the probability that a person who tests positive is actually immune (the positive predictive value). This depends on test accuracy, but also on population infection prevalence. Initial seroprevalence and modelling studies from a number of highly affected countries indicate that around 5% of the general population has been infected during the first epidemic wave [9, 10]. At this level of population infection prevalence, a person testing positive by a test that is 95% sensitive and 95% specific has even odds of being a false positive (Figure 1). Thus, if the proportion of the population infected is low, a substantial fraction of positive test results will be falsely positive and of little value in determining who should resume normal activities. In addition, viral antigenic drift could result in diminished immune protection to emergent virus strains among seropositive individuals, as happens with other coronaviruses and influenza viruses. Conversely, some individuals may never yield a positive serology test, because of immune deficiencies or other factors inhibiting antibody responses. Clear guidelines will be needed to determine when such individuals are allowed to resume normal activities, given that individuals’ infection (and subsequent immunity) status can change over time.

Figure 1.

Positive predictive value (PPV) of a serological test (y-axis) at varying levels of population infection prevalence (x-axis), for tests with different sensitivity and specificity profiles. The PPV indicates the probability that an individual who tests positive truly has been infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). For a test with 95% sensitivity and 95% specificity (dashed line), if population infection prevalence is 5%, there is a 50% chance that an individual who tests positive truly has been infected (and a 50% chance that the result is a false positive).

Given current uncertainty in how measured immune responses correlate with the level and duration of protection, policies must also consider the duration of validity of immunity passports and what consequences there would be for passport holders if they subsequently became infected with SARS-CoV-2. Waning immunity is a recognized feature of coronavirus infections, including SARS and MERS [11, 12]. Serological responses might thus signify time-limited reduction in risk of reinfection (or severe disease) rather than life-long protection. Commitment would therefore be needed for access to regular testing to monitor individual changes in serostatus over time.

POTENTIAL BENEFITS

Notwithstanding the above challenges, immunity passports have benefits beyond helping individuals to resume normal activities and facilitating economic recovery. Firstly, policies such as remote working are unfeasible for workers in some sectors. Allowing recovered individuals to resume work sooner could help optimize available state compensatory measures, by focusing support on those whose movements are still restricted due to susceptibility to infection, but who are unable to work.

Additionally, information on the serological status of workers in different sectors could inform prioritization of vaccine allocation, for example by identifying essential workers who are still susceptible to infection. Appropriate care could also be reestablished for vulnerable patient groups impacted by no-visitor policies [13], by allowing visits from family members with verified serological status.

Lastly, immunity passports could help reduce risk of international epidemic spread by serving as a permit for travel, akin to currently used vaccination certificates. This would require globally accepted test standards and compliance with the International Health Regulations (2005) [14, 15], particularly with regards to seeking “any available specific guidance or advice from the WHO” (see article 43.2 on Additional Health Measures [14]). International Health Regulations allow state parties to implement additional measures as a precaution, but these should not “be more restrictive of international traffic and not more invasive or intrusive to persons than reasonably available alternatives that would achieve the appropriate level of health protection” (article 43.1 [14]).

CONCLUSION

Potential strategies to implement immunity passport policies require a comprehensive assessment of benefits and harms, and what would least restrict individual liberties without significantly heightening the threat of COVID-19. Current scientific uncertainty on the extent and duration of antibody-mediated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 makes this challenging. Some countries are likely to push ahead with an immunity passport program to accelerate economic recovery. However, ill-conceived policies have the potential to cause severe unintended harms that could result in greater inequity, the stigmatization of certain sectors of society, and heightened risks and unequal treatment of individuals due to erroneous test results. The risk of such harms could be reduced through a centralized policy with clear guidelines on which sectors of society to prioritize for testing and rigorous mechanisms to validate test results and identify cases of reinfection. Sector-based policies that prioritize access to testing based on societal need are likely to be fairer and logistically more feasible, while minimizing stigma and reducing incentives for fraud.

Notes

Potential conflicts of interest. C. C. T. has received funding from Roche for research unrelated to this work. All other authors report no potential conflict. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. “Immunity passports” in the context of COVID-19 https://www.who.int/publications-detail/immunity-passports-in-the-context-of-covid-19. Accessed 2 May 2020.

- 2. Swiss National Covid-19 Science Task Force. Policy brief. Ethical, legal, and social issues associated with “serological passports” https://ncs-tf.ch/en/policy-briefs/ethics-of-serological-passports-22-april-20-en/download. Accessed 2 May 2020.

- 3. Kass NE. An ethics framework for public health. Am J Public Health 2001; 91:1776–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Persad G, Emanuel E. The ethics of COVID-19 immunity-based licenses (“immunity passports”) [published online ahead of print 6 May 2020]. JAMA doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall MA, Studdert DM. Privileges and immunity certification during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print 6 May 2020]. JAMA doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ploug T, Holm S, Gjerris M. The stigmatization dilemma in public health policy–the case of MRSA in Denmark. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rayda N. Indonesia clamping down on fake medical certificates used to circumvent COVID-19 travel curbs ChannelNewsAsia,21. May 2020. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/indonesia-covid-19-fake-medical-certificates-bali-travel-ban-12748770. Accessed 6 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allison I. COVID-19 ‘immunity passport’ unites 60 firms on self-sovereign ID project CoinDesk,13. April 2020. https://www.coindesk.com/covid-19-immunity-passport-unites-60-firms-on-self-sovereign-id-project. Accessed 3 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gobierno de España, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. Estudio ene-covid19: primera ronda estudio nacional de sero-epidemiología de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 en España: informe preliminar https://www.ciencia.gob.es/stfls/MICINN/Ministerio/FICHEROS/ENECOVID_Informe_preliminar_cierre_primera_ronda_13Mayo2020.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2020.

- 10. Salje H, Kiem CT, Lefrancq N, et al. . Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France [published online ahead of print 13 May 2020]. Science doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choe PG, Perera RAPM, Park WB, et al. . MERS-CoV antibody responses 1 year after symptom onset, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:1079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Temperton NJ, Chan PK, Simmons G, et al. . Longitudinally profiling neutralizing antibody response to SARS coronavirus with pseudotypes. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11: 411–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang HL, Li T, Barbarino P, et al. . Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 2020; 395:1190–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. International health regulations, WHA 58.3. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Habibi R, Burci GL, de Campos TC, et al. . Do not violate the international health regulations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 2020; 395:664–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]