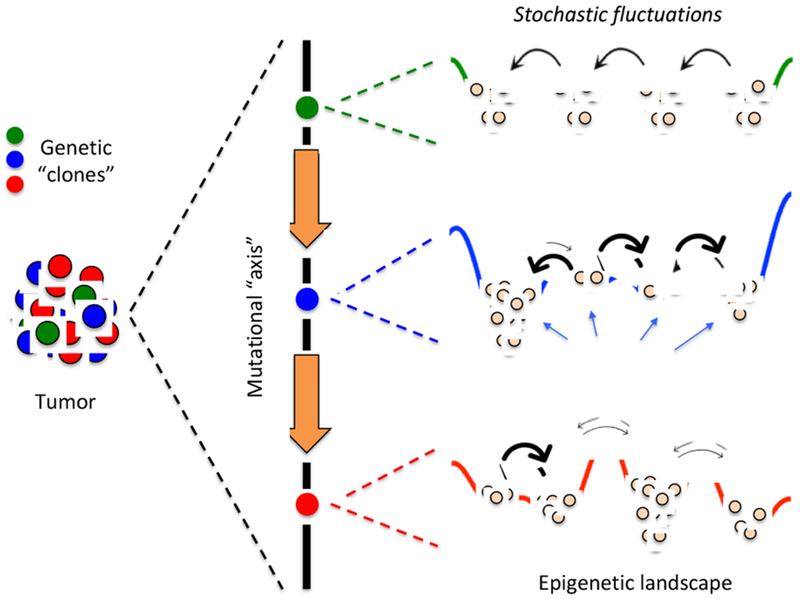

Fig 1. Three sources of intratumoral heterogeneity.

Genetic clones are cells with common origin but genetically diversified by mutations that either pre-exist or are acquired during the course of therapy [1,2]. Each genetic clone can be envisioned as existing along a “mutational axis” and having an associated “epigenetic landscape,” i.e., a quasi-potential energy surface where local minima, or “basins of attraction,” correspond to cellular subtypes [5]. From a molecular perspective, the epigenetic landscape is the consequence of the complex biochemical interaction networks that underlie cell fate decisions [6,7]. Thus, gene expression noise [8], and other sources of intrinsic (e.g., fluctuations in the production and contents of secreted factors) and extrinsic stochasticity can drive transitions between subtypes (thick arrows represent fast transitions, and vice versa). Altogether, at any point in time the subtype composition of a tumor will depend on the genetic clones present within the tumor, the topographies (depths of basins and heights of barriers) of the associated epigenetic landscapes, and the magnitudes of intracellular fluctuations within individual cells.