Abstract

Community-based participatory research provides communities and researchers with opportunities to develop interventions that are effective as well as acceptable and culturally competent. The present project responds to the voices of the North Carolina American Indian (AI) community and the desire for their youth to recognize tobacco addiction and commercial cigarette smoking as debilitating to their health and future. Seven community-based participatory principles led to the AI adaptation of the Not On Tobacco teen-smoking-cessation program and fostered sound research and meaningful result s among an historically exploited population. Success was attributed to values-driven, community-based principles that (a) assured recognition of a community-driven need, (b) built on strengths of the tribes, (c) nurtured partnerships in all project phases, (d) integrated the community’s cultural knowledge, (e) produced mutually beneficial tools/products, (f) built capacity through co-learning and empowerment, (g) used an iterative process of development, and (h) shared findings/knowledge with all partners.

Keywords: Native American tobacco addiction, teen smoking cessation, community-based participatory research

BACKGROUND/LITERATURE REVIEW

American Indians are one of the most underserved, high-risk populations with respect to U.S. tobacco control. In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that “among the five major racial and ethnic populations, adult smoking prevalence was highest among American Indians and Alaska Natives (34.1%) followed by African Americans (26.7%), Whites (25.3%), Hispanics (20.4%), and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (16.9%)” (CDC, 1997). A recent report of the U.S. Surgeon General shows that approximately 40% of American Indian and Alaska Native high school seniors smoke (CDC, 1998). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) and Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) issued a Prevention Alert in 2002 stating that 31.3% of American Indian or Alaska Native young people aged 12 to 17 have used some form of tobacco in the past month—almost twice the rate of Whites and three times that of Hispanics (USDHHS, 2002).

American Indians have a long and complex history with tobacco (Rhodes, 2000). For centuries, tobacco has been central to the American Indian spiritual, medicinal, political, and economic culture (CDC, 1998; Struthers & Hodge, 2004; Kegler, Cleaver, & Kingsley, 2000). In addition to tobacco’s role in spiritual and ceremonial events, it has also been a cash crop of significant importance to many American Indian communities (Hodge, Fredericks, & Kipnis, 1996). Although tobacco is sacred in the context of both ceremony and economy, addiction to commercial tobacco, cigarettes in particular, cannot be minimized (Fleming, Manson, & Bergeison, 1999; Rhodes, 2000; USDHHS, 1998). A study by the Indian Health Services (IHS) Cancer Prevention and Treatment Program found that 10% of all deaths in American Indians or Alaska Natives are related to cigarette smoking or use of other tobacco products, equating to more than $200 million in expenditures by IHS to provide care for tobacco-related illness (IHS, 1998). Yet almost nonexistent are prevention and cessation interventions tailored to address the complexities of tobacco use and the cultural dynamics of American Indian populations in general and American Indian youth in particular (American Legacy Foundation, 2005; Kopstein, 2001; USDHHS, 1998).

Fortunately, federal organizations are now prioritizing tobacco prevention and cessation strategies for U.S. priority populations. There is now a growing demand for culturally competent interventions that can be proven effective, then replicated and disseminated among this priority population (Hodge, 2001; Rhodes, 2000), including American Indian adolescents (Schinke, 1996). However, given the historical research exploitation of American Indians by the dominant culture, traditional research methods to develop and study health promotion interventions are unlikely to be accepted by tribes and Native communities (Davis et al., 1999; Davis & Reid, 1999; Duran & Duran, 1999). American Indians are rightfully wary of researchers. Too often Indian people have not benefited from participation in research. Moreover, “there is a dark history of federally funded research projects that were conducted without the full consent and understanding of the individual participants or their tribes” (Dixon & Roubideaux, 2001, p. 264). Importantly, concerns about research ethics and cultural relevance should not be misinterpreted into the idea that American Indians are “anti-science.” American Indian leaders and communities share with researchers the desire to discover new and effective strategies to address tobacco use and other health problems among their people (Duran & Duran, 1999). As voiced by Joseph-Fox and Kekahbah (as cited in Dixon & Roubideaux, 2001), “the best scientific and ethical standards are obtained when Alaska Natives [American Indians] are directly involved in research conducted in our communities and in studies where the findings have a direct impact on Native populations” (p. 264).

Consistently, there is a growing consensus among experts that intervention research for priority populations requires active participation of the relevant communities (Dixon & Roubideaux, 2001; Green, Daniel, & Novick, 2001; Healton & Nelson, 2004; Huff & Klein, 1999; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). One critical scientific approach that incorporates the essential standards of research rigor and ethics, and requires community inclusivity is community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Green et al., 2001; Israel et al., 1998; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Sullivan et al., 2001). By definition,

community-based participatory research in health is a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community with the aim of combining knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate disparities. (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2001, quoted in Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003)

CBPR sprang from early movements for social justice and freedom from oppression (Freire, 1970; Israel et al., 1998; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003) and has evolved as a tool for improving social and economic conditions, effecting change, and increasing trust between scientists and communities. This social justice orientation makes CBPR particularly appropriate for intervention research that addresses the needs of underserved populations, such as American Indians. For example, instead of researchers developing and testing what they believe communities need, communities and researchers partner to develop services or interventions that are not only effective but also acceptable and culturally competent. As a result, CPBR-driven approaches should have a greater likelihood of creating interventions that are sustainable beyond research funding than those using conventional research methods. Moreover, community-researcher partnerships allow for a blending of values and expertise that can result in locally relevant solutions for locally identified problems, such as tobacco control (Potvin, Gendron, Bilodeau, & Chabot, 2005).

Israel et al. (2003) articulated nine key CBPR principles. These are (a) recognizing community as a unit of identity; (b) building on strengths and resources within the community; (c) facilitating collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of the research; (d) promoting co-learning and capacity building among all partners; (e) integrating and achieving a balance between research and action for mutual benefit of all partners; (f) emphasizing relevance of public health problems and ecological perspectives that recognize and attend to the multiple determinants of health and disease; (e) involving systems development through a cyclical and iterative process; (f) disseminating findings and knowledge gained to all partners in a manner that involves all partners; and (g) involving long-term process and commitment. Israel and colleagues have cautioned that these principles should not be blindly applied as is but that the core values undergirding these principles should be broadly applicable. Moreover, they emphasize that CBPR principles are only meaningful if the relevant community owns them.

The purpose of this article is to describe the application of these CBPR principles to the development of a cigarette smoking–cessation program for American Indian youth. Consistent with the recommendations of Israel et al. (2003), these CBPR principles were modified to accommodate the unique features of the American Indian partnership. As described in this article, we employed seven of nine principles. Our perception is that Principle 6 cut across all principles and activities used in our project. Principle 9 cannot yet be determined and has not been applied at this early phase of our work. With funding from the American Legacy Foundation (ALF) and the CDC, researchers at two CDC-funded Prevention Research Centers partnered with the North Carolina (NC) Commission of Indian Affairs and NC American Indian communities to address the problem of tobacco addiction among American Indian youth. The goal of this CBPR effort was to (a) build capacity to address community-recognized health concern about teen tobacco abuse and (b) develop a culturally competent version of the American Lung Association’s (ALA) teen-smoking-cessation program, Not-On-Tobacco (N-O-T), for American Indian youth.

APPLICATION AND DISCUSSION

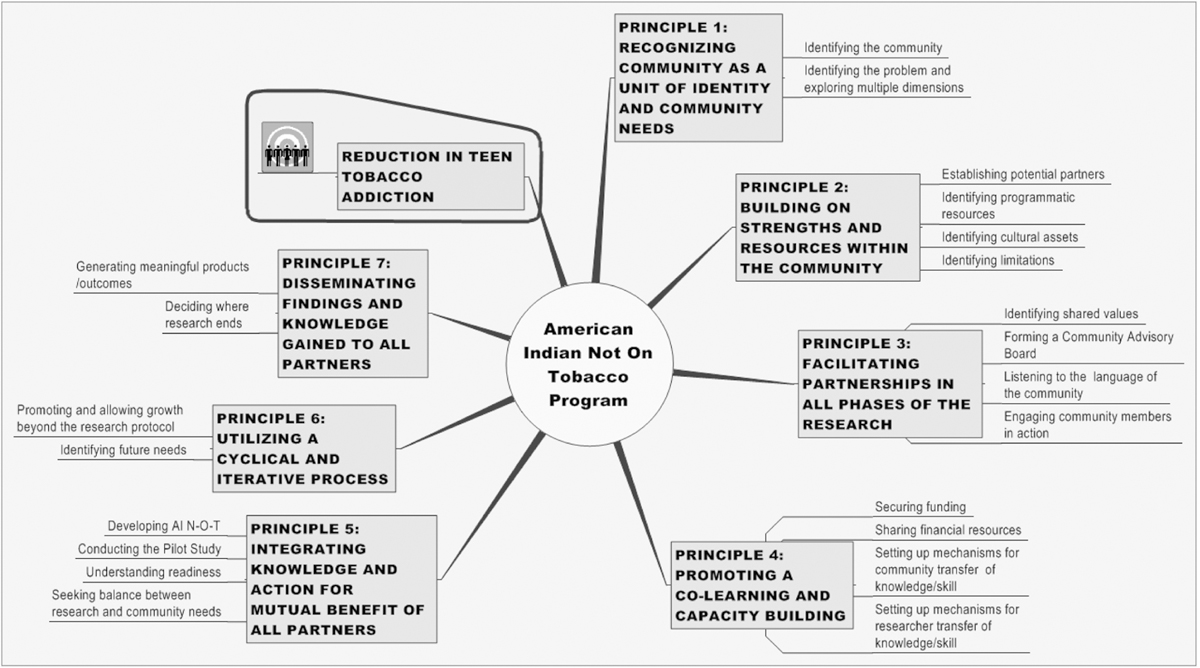

The following section details the CBPR principles (Israel et al., 2003) that guided our project (see Figure 1). We describe the interpretation and application of each principle to the final product, a culturally competent teen-smoking-cessation program, called American Indian Not On Tobacco, or simply AI N-O-T. Finally, we discuss the applications of our work to future CBPR efforts.

Figure 1.

Application of seven CBPR principles to AI N-O-T development.

Setting the Stage

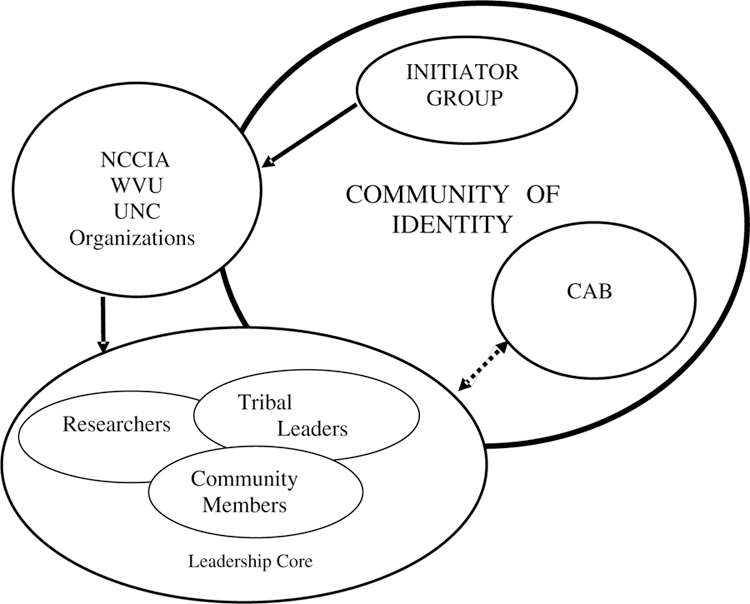

N-O-T was developed through a partnership of the WVU Prevention Research Center (PRC), ALA, and the WV Departments of Education and Public Health. Since its inception, the development and evaluation of N-O-T had involved school and community participation at all levels (Dino, Horn, Goldcamp, Fernandes, & Kalsekar, 2001; Dino, Horn, Zedosky, & Monaco, 1998). In 1998, the West Virginia University (WVU) Prevention Research Center began to implement its 5-year core demonstration project, an investigation of the effectiveness of N-O-T with rural youth. The study plan included WV and one other rural state. Simultaneously, the PRC at the University of North Carolina (UNC) had been working for years with NC school and community members to broadly address NC youth tobacco issues. Thus, the two PRCs became natural partners for collaboration on WVU’s demonstration project and began working together in 1999. The two-state demonstration project team continued N-O-T’s history of community involvement in all phases with diverse groups of rural communities in both states. In the course of the project, one of the partnering communities, a group of NC American Indians from one tribe, identified a need to specifically address the problem of tobacco addiction among their tribe’s youth. This group, which we refer to as the initiator group (see Figure 1), expressed this need to the UNC and WVU project staff. Very quickly, the WVU/UNC project staff reflected these concerns to the executive director of the NC Commission of Indian Affairs (NCCIA). The NCCIA, created in 1971 by the North Carolina General Assembly, has a mission to instill a positive vision for all NC American Indians through preserving cultural identity by promoting and advocating the rights, beliefs, services, and opportunities that impact quality of life. Following the NCCIA executive director’s formal meeting (standing tribal council meeting) with tribal leaders from all NC tribes, NCCIA leaders further reflected a strong concern about the impact of tobacco use on American Indian health and decided to work with researchers and communities to address the issue of cigarette smoking. Subsequently, a leadership structure emerged whereby researchers, tribal leaders, and community members joined together to address the identified problem (see Figure 2). Note that smokeless tobacco was not addressed because the primary focus, as initiated by the community, was on cigarette smoking.

Figure 2.

Leadership structure.

PRINCIPLE 1: RECOGNIZING COMMUNITY AS A UNIT OF IDENTITY IN RELATION TO TOBACCO USE

Identifying the Community

Community identity is a central foundation of CBPR (Israel et al., 2003). Research suggests that communities may identify themselves locally (i.e., by neighborhood) or by other factors, including geographically dispersed groups that share (a) common agendas/goals, (b) needs and interests, (c) experiences such as oppression by the dominant culture, (d) social ties, and (e) commitment to joint action (Kone et al., 2000; MacQueen et al., 2001). Interestingly, diversity of member characteristics is often emphasized around a theme of common purpose (e.g., MacQueen et al., 2001). This blending of demographic diversity with common purpose is particularly relevant for work with American Indian communities in general (Davis & Reid, 1999), and around tobacco use in particular (Spangler et al., 1999).

NC American Indians represent a very diverse group. According to 2000 federal census data, this state is home to approximately 100,000 American Indians (NCCIA, 2001), including eight tribes (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Coharie, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, Occaneechi Saponi, Sappony, Waccamaw-Siouan) and four urban associations (Cumberland County Association for Indian People, Guilford Native American Association, Metrolina Native American Association, Triangle Native American Society). CBPR principles remind researchers that communities are microcosms of individuality, possessing unique identities. In NC, for example, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is the only federally recognized tribe; the other tribes are state recognized. Moreover, each NC tribe has its own distinct culture and unique history with the dominant culture and outside institutions. In spite of these differences and distinctions, community members and tribal leaders believed that tobacco addiction was an important issue for all tribes, regardless of tribal differences. In addition, the NCCIA and its tribal council representatives believed that it would be politically and ethically unfair to select one tribe over another for tobacco-related programs and services.

Identifying and Defining the Problem

According to NCCIA leaders, the topic of tobacco addiction became one of consensus building rather than division or difference. The tribal representatives on the NCCIA unanimously agreed that the issue of youth tobacco addiction should be a priority health need across all NC tribes because the negative health consequences of commercial tobacco exceed tribal boundaries. Commission members also felt that many American Indians were impacted by the dominant culture’s transformation of sacred and ceremonial tobacco practices into a fiscal and economic exploitation. These shared values, common agendas, and shared history of exploitation resulted in the decision that all tribes should engage in joint action to address a statewide concern; thus, all NC American Indian tribes were the “community of identity” or the “community of concern.” There was also agreement that the term American Indian be applied in reference to NC American Indian communities instead of Native American.

Exploring Multiple Dimensions and Determinants of Tobacco Use Among American Indians

Although the problem of tobacco use was identified, it was necessary to explore its functional value within the community to the extent that it was linked to shared sense of history and shared fate (Unger et al., 2003). As such, following the recommendations of Struthers and Hodge (2004), it was important that

[we] recognize, be amenable to learn, and understand that sacred tobacco use and smoking commercial cigarette tobacco have separate purposes and functions. The challenge … is to retain the cultural use and value of tobacco while addressing the abuse and chronic effects of cigarette smoking… (p. 209)

For instance, NC American Indians located in the Piedmont and coastal plains regions have been greatly influenced by the tobacco economy, and tribal members recount the financial benefits of tobacco as a cash crop. The growing and selling of tobacco provided the means to obtain housing, clothing, and food, along with college tuition for a fortunate few. NC American Indians also possess a variety of opinions concerning concepts such as “sacred tobacco” (Spangler et al., 1999). Although these sacred and ceremonial practices were not usually discussed in detail with us, not all tribes use tobacco in a spiritual context. Many state-recognized tribes have embraced Protestant perspectives that consider tobacco in purely secular or commercial terms. For some tribes, tobacco is viewed as “sacred” because of the relationship with tobacco farming and economic survival rather than with spiritual practices. In summary, we learned that tobacco is sacred in the context of both ceremony and economy.

Although all tribes were seen as part of the community of identity, issues of tribal sovereignty and unique tribal-level values, customs, or characteristics were continually discussed, especially in the context of tobacco use. In fact, the blending of tribal differences with a unified commitment about nonceremonial tobacco use among youth was an ongoing feature of the project. The struggles and the resolution of those struggles helped to bring diverse groups and perspectives together. One of the most impactful examples was around identifying or framing the problem. Many community members believed that tobacco was not “the enemy” and that in order for our efforts to move forward, it was necessary for the tobacco control researchers to reframe how we thought about tobacco. A solution was identified by one community member who recommended that we identify “tobacco addiction” as the problem rather than “tobacco” or “tobacco use.” This new, community-identified “problem definition”—tobacco addiction—became the focus of the collaborative efforts that continue into the present.

PRINCIPLE 2: BUILDING ON COMMUNITY STRENGTHS AND RESOURCES IN THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF TOBACCO ADDICTION

Establishing Potential National, State, Community, and Tribal-Level Partner Organizations

CBPR prescribes that once the community of identity is determined, it is essential to identify potential partners to address the community’s health concern (Israel et al., 2003). As such, our leadership core began to contact organizations that had vested interest in tobacco abuse and in the health and well-being of American Indians. The purpose of these contacts was to publicize the community-expressed need to address youth tobacco prevention and to grow networks of relationships. These contacts were made via phone calls; personal, informal, and formal visits; and e-mails. We also relied on “natural communication channels” within the community. Specifically, interest in the project was garnered through churches and influential families within the tribes, both of which proved to be very powerful factors in our work. Some of our initial partner organizations were the following: ALA National Office, ALF, NC Department of Public Instruction, NC Indian Education Program, NC American Indian urban associations, Burnt Swamp Baptist Association, NC Health Action Council, several local health clinics, and other local grassroots organizations.

Identifying Programmatic Resources

CBPR requires building on existing strengths, including organizational and individual assets. As we expanded our partnerships, we sought information about existing tobacco-prevention programs and resources generally and tobacco-cessation programs, specifically—both in NC and nationally. In terms of cessation, no programs existed for American Indian youth or adults at the time we began our work. As a partnership, we realized that if we addressed youth cigarette smoking, we would need an intervention program. In turn, one of the most critical existing resources proved to be the ALA’s N-O-T program, which was developed by the WVU researchers involved in the current project. N-O-T was already a well-researched program. Unfortunately, only a handful of American Indian youth had ever participated in N-O-T, so we were unsure about its cultural competence. The leadership core decided that our efforts would likely include the development and research of a culturally tailored adaptation of the N-O-T core program. However, we knew that this decision had to be made with additional community input and consent. As such, the NCCIA organized a large community meeting for all tribal council leaders and guests from their respective tribes. During this meeting, WVU/UNC researchers presented facts about tobacco use among American Indian youth, the current deficiencies in terms of cessation programs for American Indian youth, and the basic tenets of CBPR. In addition, information about the N-O-T program was presented. After extensive discussion, meeting attendees decided to proceed with the understanding that we would develop a cultural adaptation of the N-O-T program.

Identifying Assets Related to American Indian Culture

As some researchers emphasized (McKnight & Kretzmann, 1993), communities of color often possess innate cultural assets, including networks of relationships. It is important to understand how these assets (e.g., value of elders, appreciation of social and economic contexts of behavior, survival in the face of frustration, family networks, etc.) facilitate CBPR efforts. For example, in our community, family networks were invaluable for passing information, generating support, and reaching deeper into the community. The family is a cherished institution in American Indian communities, and family relationships are a natural resource for health promotion. Informal discussions indicated that family, tribe, and community must come before the individual as we progressed in our efforts. In fact, adults and youth alike held negative perceptions of putting self above the family or community. In our travels to various tribal areas across the state, it was common practice for American Indians to seek out family connections with other American Indians. For example, the question “Who are your people?” became a familiar one as we visited different tribal areas. Through discussion of surnames, people frequently identified a common friend or relative; surnames were used to determine relationships within the community and to each other. A sense of family identity and connectedness was established through the identification of these relationships. As has been the case in other priority-populations research (Caldwell, Zimmerman, & Isichei, 2001), these relationships were the backbone of our efforts.

Identifying Limitations

As a function of identifying resources, the leadership core also identified several limitations to addressing youth tobacco cessation. Identifying limitations was important because it helped us to understand where we might face our greatest challenges. Community members were able to quickly identify social structures and social processes that served as barriers.

Limited data on tobacco use rates among NC American Indians. At the time we began this project, there were no valid statewide prevalence data on tobacco use among NC American Indian youth or adults. Although some “spot” data from a statewide asthma survey were available to project prevalence rates for youth (Yeatts, Shy, Sotir, Music, & Herget, 2003), no data existed at the tribal level.

Lack of a culturally tailored youth-smoking-cessation program. Although we agreed that we would build on the existing N-O-T program, we were keenly aware that it would take time to develop a culturally tailored version.

No funding for our efforts. Our initial partnership was supported by goodwill and good faith. At this time, few state resources were available in NC for tobacco control efforts generally, much less for American Indians. In addition, few federal or private foundations offered funding for tobacco prevention and cessation for American Indians. We knew that funding was necessary if we were to further pursue our agenda to develop a culturally tailored teen-smoking-cessation program.

Sociocultural context of attitudes toward tobacco. Separating a destructive and addictive behavior from the tobacco economy of the state (and the American Indian people) was challenging. The leadership core was concerned that some community members would not be able to distinguish between our addressing tobacco addiction and attacking a cherished industry (Shorty, 1999; Spangler et al., 1999; Struthers & Hodge, 2004).

Concerns about historical research exploitation among American Indians. Undoubtedly, we could not overlook or minimize this legitimate concern, especially because several of the research team members from WVU and UNC were White. The leadership core was concerned that historical research exploitation would limit the research and evaluation of our efforts at the grassroots level of the community.

PRINCIPLE 3: FACILITATING COLLABORATIVE, EQUITABLE PARTNERSHIPS ACROSS ALL PHASES OF RESEARCH

Identifying a Shared Set of Values

Within 6 months from the time the initiator group brought their concerns to WVU and UNC, the leadership core expanded to 8 to 10 individuals, representing researchers, tribal leaders, and community members. Refer back to Figure 2. This group eventually grew to include 17 individuals. CBPR involves a power-sharing process that acknowledges the marginalization of certain communities and reinforces the concepts of mutual decision making and problem solving in research designed to reduce health disparities (Davis & Reid, 1999; Israel et al., 2003; Kone et al., 2000; Sullivan et al., 2001). This belief was clearly reflected in one of the initial meetings of our expanded leadership core. The group decided that our efforts to develop an American Indian teen-smoking-cessation program must be values driven and clearly reflect the consensus of equitable partnerships throughout all collaborative work. The leadership core identified a set of core values that would guide our partnership. The belief was that if our research was driven by a meaningful set of values and if those values were consistently communicated to community members, we could establish new and equitable means of research.

An initial set of values was generated and discussed among the leaders. To increase the meaningfulness of these values to the larger community, approximately 11 community members were solicited to provide feedback. They were mailed or e-mailed a document that contained all the values and were asked to define them in their own words. Responses were sent back to researchers and then summarized by leadership core members. The result was the following set of core values, and each had an accompanying definition:

| Honor leadership | Trust | Collaborativeness |

| Honor elders | Respect | Inclusiveness |

| Honor tribal/cultural protocol | Honesty | Cultural sensitivity |

| Stewardship | Transparency | Capacity building |

| Integrity | Open to change | Striving toward consensus |

| Accountability | Open communication | Levity |

| Service | Responsibility |

These core values were used in many ways. To illustrate, the values were (a) distributed to all partner organizations and individuals who joined the effort at any phase throughout the project, (b) reviewed before meetings, (c) revisited during times of difficult decision making or conflict, and (d) highlighted in project print materials distributed to community members. Ultimately, the articulation of these values shaped the entire collaboration described in the article. One of the clearest examples of this was the formation and function of the project’s Community Advisory Board.

Forming a Community Advisory Board (CAB)

To assure equity in tribal representation and to maximize participation, the leadership core felt that the advising body for the overall effort should be representative of the entire “community,” with members from each of the NC tribes and urban associations. Through many telephone calls, e-mails, letters, and face-to-face meetings, the initial AI N-O-T CAB was formed. Established in 2002, the CAB consistently grew from a small group of 25 to its current membership of 190 adult and youth members. Over the years, the CAB (a) facilitated entry to school and community sites; (b) assisted in the development of study methods, procedures, and reporting formats; (c) educated researchers on cultural issues and values; (d) reflected community views and values about the research process, needs, and interests; (e) promoted community trust for the projects; and (f) promoted outcomes at practice and policy levels. In 2003, the CAB decided to name itself the Many Voices, One Message: Stop Tobacco Addiction CAB. This name reflected and reinforced the concept of “blending of diversity with common purpose” mentioned earlier. They also selected a logo that was designed by a local Native artist. Both were selected by majority vote from a list of community-generated samples. The stated mission of the Many Voices, One Message CAB is “building capacity with NC American Indian people to promote health and prevent the addiction, disease, and death from tobacco use.” The transformation and growth of the Many Voices, One Message effort reflected the community’s commitment to tackle tobacco addiction.

Listening to the Language of Our Partners

CBPR requires that individuals have the opportunity to name and define their own experience in a project. Active listening on behalf of the researcher is an essential element of this process. The CAB continually provided guidance on the ways that our tobacco language could be facilitator or a barrier to effective partnering. Although the problem was defined early on, our framework of “the tobacco problem” (i.e., tobacco addiction vs. tobacco use) and the words used to describe tobacco-related actions had to be continually considered (Oberly & Macedo, 2004). Similar to other tobacco-prevention efforts with American Indians (Kegler, Cleaver, & Yazzie-Valencia, 2000), addressing the harmful consequences of tobacco in our community was acceptable when discussion and activities occurred in the context of “tobacco addiction” rather than using the sweeping, generalized term of “tobacco use.” It was important to help teens and other community members develop a vocabulary to discuss the traditional role of tobacco in their culture separately from habitual or addictive use (Flannery, Sisk-Franco, & Glover, 1995; Kegler et al., 2000). As a result, we maintained a focus on “commercial cigarette smoking” rather than “tobacco smoking,” which is an acceptable ceremonial ritual (Shorty, 1999). One community member poignantly explained, “Addiction is an evil spirit; [tobacco is not].”

Engaging and Maintaining Partners and Community Members in Action

Community members must view their roles as important and meaningful. Moreover, they must be empowered to act. We used a variety of venues to inform, excite, and engage community members throughout the entire project. Conferences, powwows, CAB meetings, and tribal council meetings provided excellent opportunities to network and dialogue about the project within existing systems and structures. In addition, the work of the Many Voices, One Message CAB was highlighted at several key annual meetings, including the Annual NC Indian Unity Conference (sponsored by United Tribes of NC) and Annual Indian Youth Unity Conference (sponsored by the NC Native American Youth Organization [NCNAYO]). These venues also proved to be invaluable for engaging participation in interviews, focus groups, and spontaneous storytelling—all of which informed the development of AI N-O-T.

PRINCIPLE 4: PROMOTING CO-LEARNING AND CAPACITY BUILDING TO ADDRESS TOBACCO ADDICTION

Securing Grant Funding

Clearly, fiscal resources are a critical requirement to support co-learning and capacity building. Our first step to increase capacity was through the procurement of fiscal resources. The leadership core began to secure funding in 2001. The academic researchers led the technical aspects of the grant-writing process. Community partners shaped research ideas, formulated research questions, and reviewed and edited the applications. Our first grant application was not funded, but our second attempt was successful. We received a 1-year grant from the ALF to begin American Indian youth-tobacco-cessation capacity building. In 2002, we secured another 2-year grant from ALF to develop and pilot test the AI N-O-T program. Also in 2002, the CDC funded our efforts to address the American Indian teen tobacco addiction using a social-ecological approach, which also included further pilot testing of the N-O-T program. Through all three funded efforts, we sought to (a) “ready” the community to reduce youth smoking by fostering a favorable environment for youth tobacco intervention and education; (b) empower the community to make informed and meaningful data-driven decisions about tobacco cessation and education programming needs and gaps and tobacco-related health risks; (c) provide access to effective, culturally tailored youth cessation; (d) facilitate family education and support for youth smoking cessation; and (e) enable the community to sustain the cessation and education programs beyond the funding period via policy and practice changes.

Sharing Financial Resources

The leadership believed that it was essential to share resources to the fullest extent possible—not only among primary partner organizations but also with community members and tribes. This sharing reflects and reinforces the principles of partnership equitability (Principle 3) and provides some necessary resources for ongoing systems development (Principle 7). Conventionally, research funding remains within the academic institution of the researcher. In our project, the primary partners in the leadership core worked out agreeable divisions of project labor and associated costs prior to submitting the grant applications. Grant funds were divided equally among the three primary organizations (WVU, UNC, and the NCCIA), and each organization had monetary control over their resources. In addition, all grants included monies to be provided to community members or tribes to cover project-related costs (e.g., implementation stipends, travel, hospitality, copy costs, and incentives). The N-O-T facilitators also were paid stipends for their efforts. In addition, 12 of 17 leadership core members were American Indian and were provided paid positions through the project. Moreover, through funding from the NC Health and Wellness Trust Fund, the NCCIA provided a mechanism to support tribal capacity-building tobacco control activities via competitive mini grants.

Setting Up Mechanisms for Community Transfer of Knowledge and Skills to Researchers

Consistent with CBPR principles, the leadership core and CAB believed that co-learning and capacity building for all partners was a requirement of our work together. NCCIA partners and tribal leaders recommended books, articles, and other literature that enabled non-Native researchers to better understand the strengths and challenges of tribal communities. Researchers spent time with community members who shared personal stories concerning disease and death resulting from tobacco addiction. Their stories revealed the nature of the relationship between tobacco agriculture and survival, explaining the financial benefits afforded some NC American Indian families by raising commercial tobacco. Community members further explained that tobacco farming was essentially the only local economy in which American Indians could participate. As one community member stated, “There were no industries available to speak of. Most of this population lived in rural areas where farming was a necessity for survival.” Importantly, community members helped the researchers to better understand the meaning of tobacco, tobacco histories, and relevant aspects of American Indian culture and attitudes toward health. Listening and being attentive to community perspectives fostered trust. One high-level tribal leader told the researchers, “You listened more than you talked. I have trust for you because you were willing to say ‘I don’t know [the answer].’”

Setting Up Mechanisms for Researcher Transfer of Knowledge and Skills to Community Members

A primary goal was building community capacity to address youth tobacco addiction. This was accomplished, in part, by teaching community members about research and evaluation and by redefining research in terms that were acceptable to community members. Project staff and other community members received training on N-O-T and AI N-O-T, grant writing, research methods, data collection, and CBPR strategies. Among all primary partner team members (NCCIA, UNC, and WVU), only three ever had been involved in any type of research. Many team members were community-based professionals who also were members of the American Indian community. Although team members were loyal to the AI N-O-T project, many also brought understandable reservations about research. Community-based researchers sometimes felt conflicted in the roles as both researchers and community advocates. We held frequent team conversations about the meaning of research in the context of our project. Hands-on research training was an ongoing part of the project. These activities facilitated trust and rapport among community members and researchers. Importantly, although researchers introduced the term CBPR to our community-based partners, CBPR-focused strategies were naturally aligned with tribal ways; Native populations have followed the basic tenants of community-driven efforts for centuries.

PRINCIPLE 5: INTEGRATING AND ACHIEVING A BALANCE BETWEEN RESEARCH AND ACTION FOR MUTUAL BENEFIT

In CBPR, knowledge and social change efforts are integrated in a manner suitable for addressing community concerns, and that will have benefit for all partners (Israel et al., 2003). This principle is most clearly reflected in the actual development and testing of the AI N-O-T curriculum, a behavioral change intervention designed to reflect current state of the art in adolescent smoking cessation with American Indian cultural competence. Translated into action, these processes involved ongoing partnership (i.e., a system); development that included culturally competent needs assessment; development of research methods; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; dissemination of results; and movement beyond the original project aims.

Developing the AI N-O-T Program

Although AI N-O-T was developed through iterative input from community members, it was based on the American Lung Association’s Not On Tobacco program (i.e., N-O-T). N-O-T is a gender-sensitive, school-based adolescent smoking-cessation program (Dino et al., 1998). To summarize, N-O-T is designed for 14- to 19-year-old youth who are regular cigarette smokers likely to be addicted to nicotine, who volunteer to participate, and who want to quit smoking using a group program. N-O-T includes 10 hour-long weekly sessions and 4 booster sessions delivered to males and females separately by male and female facilitators. Groups are held in private settings with no more than 12 youth per group. N-O-T has been demonstrated as an effective model program for youth who want to stop smoking (Horn, Dino, Kalsekar, & Mody, 2005). It is recognized as a Model Program by SAMHSA and the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) and as a National Cancer Institute Research-Tested Intervention Program and is an ALA Best Practice.

Several steps were taken to adapt N-O-T for American Indian youth and to incorporate community knowledge and experience into the new program. First, an exhaustive review of the scientific literature on American Indian tobacco use and an examination of other culturally tailored tobacco-related programs and services, including culturally competent learning styles and strategies that address the needs of American Indian youth, was undertaken to gather the information needed to tailor the curriculum. Incidentally, this exhaustive review was published in a Community Resource Guide and distributed to all tribal councils (Centers for Public Health Research and Training, 2005).

Second, the process to culturally adapt the N-O-T curriculum for NC American Indians required talking with community members individually (e.g., face-to-face interviews, phone calls) and collectively (e.g., formal and informal meetings, focus groups) about tobacco-related behaviors. Community members showed support by sharing personal testimonies, stories, histories, and anecdotes. Open discussions on youth tobacco addiction occurred at CAB meetings and during community visits. As one tribal leader touted, “There is no project like this in the country.”

Third, youth and adult focus groups and subsequent pilot testing were the most critical aspects of the cultural adaptation process. Small groups of American Indian youth in three school/community sites had the opportunity to react to every session of the N-O-T core program (prior to adaptation). Their reactions were recorded on N-O-T session-by-session reaction forms by the program facilitators during their active participation in the program. Initial feedback from youth suggested a need to adapt the N-O-T curriculum to show American Indian stereotyping, exploitation by the tobacco industry and media, and historical perspectives on the functional value of tobacco. American Indian youth also asked for a greater focus on group identity versus individually focused cessation efforts. Discussions with the CAB and other adults and youths from the community revealed similar findings. Overall, feedback emphasized the inclusion of (a) an American Indian perspective on the history of tobacco, including ceremonial and traditional origins of tobacco and changes over time as well as the differences between tradition and addiction; (b) a greater focus on group identity and cohesion rather than individual efforts; (c) tobacco use rates and health consequences specific to American Indian populations; (d) interactive, problem-solving learning methods that incorporate culturally appropriate and diverse learning styles with a range of options for cultural and traditional activities; (e) the use of visual teaching aids, including culturally appropriate graphics, tailored print media, and tobacco prevention and cessation materials with cultural themes reflected in handouts to youth; (f) increased focus on the impact of a teen’s smoking on family and community, including effects of secondhand smoke on family members; (g) promoting youth advocacy and youth leadership; and (h) using activity options that involve family members and encourage their support for youth participating in the AI N-O-T program. See Table 1 for AI N-O-T curriculum review and the session titles.

Table 1.

American Indian N-O-T Curriculum Highlights

| Review Factors | AI N-O-T Preliminary Curriculum |

|---|---|

| Theory base | Social cognitive theory (SCT) |

| Research foundation | American Lung Association’s Not On Tobacco Program, which was based on Project Toward No Tobacco (Sussman et al., 1993), social development model (Hawkins & Catalano, 1987), Freedom from Smoking, transtheoretical model (Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente, & Fava, 1988) |

| Stage of Development | N-O-Tis a model program; AI N-O-T is in the formative evaluation, pilot-testing phase |

| Intervention type | School-and community-based |

| IOM classification | Selective/secondary, tertiary |

| Primary target | 14- to 19-year-old American Indian teens |

| Content focus | Risk and protective factors affecting tobacco use and cessation among American Indian teens |

| Protective factors addressed | Individual: social skills, emotional regulation, positive sense of self, problem-solving skills, tobacco attitude/knowledge. Peer: Positive involvement with peer group, healthy norms, social competencies such as decision-making skills, assertiveness, and interpersonal communication. School: caring/supportive school/community environment, bonding with school personnel. Community: involvement in leadership, advocacy, and volunteerism; recognition of tobacco history and tobacco culture |

| Intervention domains | Individual, school, peer |

| Duration | 10 hour-long sessions, 1 hour per week. Up to 4 booster sessions/1 hour/4 per 3 months |

| Size of groups | Groups of no more than 12 teens. Groups are conducted in same gender groups |

| Time offered/location | During the school day at school (when delivered at school). Per community convenience (when delivered in the community) |

| Staff needs | Certified N-O-T and AI N-O-T facilitators (e.g., teachers, counselors, nurses, etc.), one per AI N-O-T group |

| Training | 1- to 2-day (10-hour) training required by the American Lung Association to become certified in N-O-T core program. Additional 4 to 6 hours for AI N-O-T certification. A few of the features of AI N-O-T training include (a) introduction (e.g., American Indian teens and tobacco addiction, overview of AI N-O-T), (b) facilitator roles and responsibilities (e.g., breaking barriers and challenging stereotypes, seeking referrals for additional services), (c) delivering AI N-O-T (e.g., power of human connections, power of connection to nature, power of faith and spirit, power of shared values), and (d) session-by-session training |

| Other special needs/resources | Private group meeting room, copy of all curriculum materials, incentives optional |

| Session Titles | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. About the AI N-O-T Program | Program overview, forms, and logistics |

| 2. Getting Fired Up to Quit | Motivation issues and reasons for smoking |

| 3. Working It Out With Myself and Others: Me Without My Smokes | Stress management, smoking history, and nicotine addiction |

| 4. Body, Mind, and Spirit: Before | Physical, psychological, and social effects of smoking |

| 5. The Big Quit Day | Preparing to quit, urges and cravings, and benefits of quitting |

| 6. Stopping Addiction Once and for All | Urges, cravings, and relapse prevention |

| 7. Body, Mind, and Spirit: After | Stress management and healing |

| 8. Working It Out With Friends and Family | Dealing with family/peer pressure |

| 9. Helping Myself and Helping My Community | Volunteerism and recognizing social/cultural/media ploys |

| 10. Staying Committed to the Greater Good | Renewing smoke-free pledges and accessing resources and support |

Conducting a Pilot Study of the New AI N-O-T Program

Insights obtained from the CAB meetings and communication with community partners via informal discussions, meetings, and electronic methods resulted in the identification of community partners who participated in pilot testing. Specifically, the CAB recommended ways to (a) obtain school and community site support for AI N-O-T implementation, (b) approach and recruit youth into the program, and (c) obtain honest, direct feedback from youth and adults on the cultural appropriateness of N-O-T. Final sites for the AI N-O-T pilot study were selected with the guidance of the NC Indian Education Program and the NC Department of Public Instruction. In addition, the ALA-NC provided guidance on locating schools that serve American Indian youth and that already had trained N-O-T facilitators in place. Prior to pilot study startup, these facilitators were provided additional training in AI N-O-T. The ALA-NC also worked with the leadership core to provide a 2-day N-O-T and AI N-O-T training to facilitators who had not previously implemented N-O-T. Consistent with the recommendations of Green and Mercer (2001), community members helped in the formulation of research questions, selection of study design and methods, and data interpretation. Our first pilot study was sufficiently carried out with a sample comprised of 74 youth (n = 54 AI N-O-T youth and n = 20 brief-intervention comparison youth). Overall, 82.2% of youth were American Indian. Among AI N-O-T males, between 29% (compliant subsample) and 18% (intention-to-treat) quit smoking. Twice as many males in the AI N-O-T program reported quitting smoking compared to males receiving the brief intervention. No females quit smoking, but more AI N-O-T females reduced smoking than females in the brief intervention. For complete details on the pilot study findings, see Horn et al. (2005).

Understanding and Accepting States of Readiness

An important part of sustained mutual benefit is acceptance and understanding of community readiness to change behavior. Researchers and community leaders cannot force community members into change for which they are not ready or prepared. We discovered two central “readiness” issues in our work with NC American Indians around tobacco addiction. The first pertained to the state of readiness of the individual schools and school systems to “take on” a teen-smoking-cessation program. During this project, the NC Department of Public Instruction did not have a mandated school tobacco control policy. Therefore, the states of school readiness to implement teen-smoking-cessation programs varied greatly. To assess readiness for implementation of AI N-O-T, we assessed the current tobacco control climates by determining whether the school had a tobacco-free policy in place, the degree of enforcement of the policy, the number of trained core N-O-T facilitators present at the school, their experience with N-O-T, school-based youth tobacco prevention and advocacy groups, and alternatives to suspension programs. In most instances, the school system’s approval was required for a school participation. The second “readiness” factor related to youths’ willingness to join the AI N-O-T program. In several sites, youth appeared reluctant to quit smoking. In spite of tribal leaders’ readiness to address tobacco issues, readiness varied notably within the tribes and communities and among the youth. Although community leaders were ready to intervene with tobacco use among youth and adults, community members were not consistently at the same level of readiness, especially the youth. Hypothetically, if we used the transtheoretical model (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992; i.e., stages of change) construct to gauge overall community readiness to quit tobacco use, it would likely be between precontemplation and contemplation. The marginal state of readiness did not vary notably by tribe. Clearly, both system-level and individual-level readiness must be considered when addressing tobacco addiction in Native communities.

Seeking Balance Between Research Protocol and Community Needs for Mutual Benefit

NC American Indian communities face many challenges to improve education, health care, and economic opportunities in the context of limited resources. Moreover, tribes and urban associations need programs and service delivery models that can be put in place as rapidly as possible and easily adapted to a variety of needs and circumstances. Sometime having the scientific “proof” of effectiveness competes with this urgency (Doll et al., 2001). In addition, a negative experience with previous research projects may even discourage some communities and individuals from participating in research (Green & Mercer, 2001). Simultaneously, researchers are faced with issues involving scientific rigor, research protocol, university policies, and funding requirements in the context of limited time and resources. Community-research partnerships must continually balance these different needs and perspectives while focusing on the common agenda to serve the community. Our leadership core had frequent discussions about promising only what we could deliver to the community. American Indian elders and leaders reminded us that many researchers have promised results and benefits for the community, with few actually delivering on the promise (Green & Mercer, 2001). A trail of broken promises runs through most Native communities.

All members of the leadership core agreed that we would undoubtedly produce and deliver the AI N-O-T program. The debate occurred, however, related to when and to what extent. In the context of AI N-O-T development, researchers held biases about rigorous research and scientifically acceptable standards of evaluation. Acceptable standards of intervention testing can take many years to achieve. Tribal leaders and our community-based team members were driven by the community’s urgent need for a teen-smoking-cessation program. Herein, our greatest debate manifested. To overcome these challenges, researchers and community members agreed to complete the AI N-O-T program in “draft” form and to pilot it as quickly as possible—even though we didn’t consider the program completed. The actual time from writing the curriculum to pilot testing was less than 6 months. By releasing the program for evaluation through pilot testing, with the understanding that it was not a final product, both researchers and community members were satisfied. As stated by one academic researcher, “There is often a misperception among researchers that CBPR is not scientific. Our research shows that CBPR provided a nest for supporting and fostering good science, including an intervention trial.”

Gaining Strength Beyond the Initial Goal

Although the project initially focused on teen-cigarette-smoking cessation, capacity-building efforts helped to identify other areas of tobacco control that the community wanted to address. For example, UNC applied for funding from the NC Health and Wellness Trust for elder-youth tobacco prevention teams. In addition, faith-based leaders initiated efforts to address tobacco addiction from a spiritual perspective and, in turn, received funding from the NC Health and Wellness Trust Fund. These projects helped to empower the community to move toward a comprehensive tobacco prevention and control initiative. In fact, the Many Voices, One Message CAB, with support from the leadership core, broadened its focus to include four key areas: (a) teen cessation (i.e., AI N-O-T); (b) Home, Heritage, and Health, a faith-based effort to provide education in a spiritual context on the health consequences of tobacco addiction, including promotion of tobacco-free church and home environments; (c) resource sharing via mini grants to promote equity for tobacco-prevention capacity building for all NC tribes, associations, organizations, and faith-based communities (funded by a grant obtained by the NCCIA); and (d) training and technical assistance for all tribes using N-O-T or AI N-O-T; tobacco-free policies for homes, churches, schools, and traditional activities; youth-elder educational and advocacy efforts; and participatory research methods. These projects were intended to empower the community to move toward a comprehensive tobacco-control initiative.

PRINCIPLE 6: USING A CYCLICAL AND ITERATIVE PROCESS FOR SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT TO ADDRESS TOBACCO ADDICTION

Promoting and Allowing Growth Beyond the Research Protocol

Although the project focused on AI N-O-T and teen-smoking cessation, capacity-building efforts helped to identify other health disparities of concern to the community, not all of which were related to tobacco control. New community needs were reflected with each CAB meeting, with each iteration of the AI N-O-T curriculum, with every story told. What we learned about “Principle 6: Involving a cyclical and iterative process” is that iterative does not necessarily mean repeating the same process or re-addressing the same need. When a process is iterative, new issues may emerge, and researchers and community members must decide to what extent they will deviate from the initially stated problem. In response to community growth and willingness to voice other needs, other health-related needs emerged, including (a) alcohol addiction, (b) diabetes, and (c) obesity. Although these issues were outside of the scope of our project, the NCCIA highlighted these issues for planning during future state tribal council meetings.

Identifying Future Research Needs

Building on our increased competencies, the second pilot examination of the AI N-O-T curriculum is currently under way. As suggested by Israel and colleagues (1998), our curriculum adaptation is a cyclical process, and the AI N-O-T program remains in an evaluative state. A less research-rigorous, more “real-world” assessment of AI N-O-T is planned as well as a family education module. As highlighted by community input, major questions to consider in future research and evaluation of AI N-O-T include How can we improve recruitment of youth into cessation programming? What strategies are effective for moving youth along the stages of readiness to quit? How can we further engage community members in community- and environmental-level changes to promote cessation? What are the best ways to involve parents and families in smoking-cessation activities? As one American Indian youth stated, “We need our parents to join N-O-T!” And an AI N-O-T facilitator said, “We must involve families somehow, since the home use of tobacco undermines what N-O-T and the schools are doing.”

PRINCIPLE 7: DISSEMINATING FINDINGS AND KNOWLEDGE GAINED TO ALL PARTNERS

Generating Meaningful Products and Outcomes

As O’Fallon and colleagues pointed out, CBPR can result in countless outcomes, quantitative and qualitative (O’Fallon, Tyson, & Dearry, 2000). We had many project outcomes beyond the development of AI N-O-T—some expected and some unexpected. Some of them were measurable and others were not. The project partnership shares credit equally by listing all project team members, tribes, and the project logo on all products. Consistent with the CBPR recommendations of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (O’Fallon et al., 2000), we list examples of our most important outcomes in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of Key Project Outcomes

| Trust between researchers and community | Historically, American Indian communities have been “subjects” rather than full partners in the research process. Indicator: As demonstrated by the growing Many Voices One Message CAB, continued partnering, and sustained involvement in AI N-O-T, active participation by all partners in CBPR reduced the skepticism of research and allowed our project to achieve many successes. |

| Increased relevance of identified need | Sacred, economic, and ceremonial value of tobacco were separated from addiction. As such, the functional value of tobacco was identified in a meaningful and acceptable cultural context within the larger community. Indicator: This relevance was reflected in the CAB-selected project logo: Many Voices, One Message: Stop Tobacco Addiction. |

| Increased use and relevance of data | Community feedback was an iterative process of interviews, focus groups, and informal storytelling and was used to develop, tailor, and evaluate the new AI N-O-T program. As one AI N-O-T facilitator exclaimed, “This is something that will be big for our school.” Indicator: Community members and researchers published the pilot study results in two formats: (a) a scholarly publication, currently in press, and (b) a community-friendly report, with 500 copies disseminated. |

| Increased tools and resources | One resource for the community is an organized CAB. Indicators: The CAB currently consists of 190 members, including 50 youth representing all NC tribes and Urban Associations. Emergent products included the AI N-O-T program, resource and educational guides, graphic maps that included tobacco-related morbidity and mortality rates at the tribal level, skill-based grant writing and evaluation training for community members, jobs, and new financial assets for teen tobacco addiction totaling more than $2 million. Another example included tribal-level mini grants. Nine tobacco-related mini grants were awarded by the NCCIA through funding provided by the NC Health and Wellness Trust Fund Corp. Relevant to the Many Voices effort, recipients were required to receive training in N-O-T core program and conduct the program in their community. |

| Increased dissemination | Because the community actively participated, they were more willing to assist in dissemination of information about the project as well as our outcomes. Indicators: Information about the project was communicated via multiple channels of tribes, urban organizations, churches, and the NC Commission of Indian Affairs. In addition, partners provided numerous community workshops, training, and professional poster and podium presentations. For example, project team members and partners conducted 18 presentations about AI N-O-T and tobacco addiction in churches, reaching more than 1,000 attendees. |

| Translated research into policy | Indicators: The NCCIA is actively working with the NC Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and the Indian Education Program to integrate AI N-O-T as a part of its required health education curriculum. Currently, the NCCIA has taken an active role to create legislation for commercial tobacco-free powwows, tribal meetings, and church activities. Two NC tribes have now taken steps to hold tobacco-free powwows. In addition, the 2005 NC American Indian Unity Conference had its first-ever commercial tobacco-free conference. These are historical events. |

| Emergence of new research questions | Active community participation was the springboard for new research ideas. Indicators: Some of the new community-driven research questions related to measuring community readiness to address tobacco, barriers to cessation among female teens, and general smoking-cessation recruitment barriers among youth. We already have received new funding to study recruitment barriers. |

| Extended research and intervention beyond the original project | Indicator: New funding has been secured to explore recruitment challenges limiting program participation in AI N-O-T among NC youth. |

| Improved infrastructure and sustainability | Many Voices CAB is an example of improved capacity and infrastructure. Indicators: Six formal CAB meetings were held between 2002 and 2004. Moreover, the NC Commission of Indian Affairs continues to work closely with the NC DPI Indian Education Program to offer AI N-O-T and other tobacco education efforts. ALA NC continues to offer training in N-O-T statewide. As part of our project, 34 people were trained in N-O-T, 25 in AI N-O-T, 16 received research protocol training, and 7 were trained as BI facilitators. Also, among 13 leadership core members, 8 were American Indian. |

Deciding Where the Research Ends

An important feature of dissemination is using results to inform future action. Our team agreed up front that many of our “value-added” efforts would not be quantitative research products. Immediately we learned that the community craved knowledge and information about tobacco addiction and tobacco-related illness. In fact, our project triggered a chain of unplanned tobacco-related events and activities across tribes and communities. These efforts moved (and continue to move) quickly through natural channels and were almost impossible to track or document for research purposes. Demonstrating increasing competency and capacity, educational and advocacy efforts for tobacco prevention and cessation among American Indians are flourishing across the state—many initiated by members of our CAB and our partnership. It is not uncommon to hear about AI N-O-T and the work of the Many Voices, One Message CAB at powwows, statewide conferences, church meetings, and tribal council meetings. Our statewide project served as a springboard for localized planning and action. Many AI N-O-T facilitators voiced a desire to recruit youth into the program without the research-intensive consent process. They believe recruitment will be more successful without the research stigma and requested the opportunity to implement the program under “real-world” conditions. With that, the researchers were faced with the difficult decision of pulling back with controlled research trials to “free” the community from research constraints. The leadership core agreed that the increased comfort and understanding of the AI N-O-T program at the community level will likely increase the implementation and success of future controlled trials. The leadership core asserts that this is a compromise that benefits all stakeholders. In CBPR, a researcher must honestly assess whether or not research requirements stand in the way of progress at any point in the project. The evaluation of programs such as AI N-O-T includes multiple phases (e.g., pilot testing, efficacy testing, effectiveness testing) and multiple iterations. Accordingly, CBPR principles emphasize reciprocity and iteration. Certainly, pilot testing can inform application. Conversely, “real world” application can inform research. If we are letting the community lead, we must be willing to follow. Consequently, the next phase of our research involves “real-world” implementation in which facilitators agreed to discuss their experiences and program results with the leadership core on program completion.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Listen to Community-Identified Needs

Understanding and operationalizing the identified need or problem requires understanding the language and historical context of the problem. It also requires summarizing the problem with brief but meaningful language as spoken by the community. For example, the voices of our community consistently articulated concern about tobacco use among youth. Our project “tagline” captured the relevance of the problem: Many Voices, One Message: Stop Tobacco Addiction. In essence, tribes wanted their youth to (a) recognize the debilitating effect of tobacco addiction on their health and their future and (b) to cease commercial cigarette smoking.

Build on Strengths of the Community of Identity

Although our community did not have existing resources related to tobacco prevention and cessation, other strengths provided an important foundation for our work. Some of these included strong family ties, common customs and traditions, and natural networks for communication through tribal relationships and churches. As one local minister stated, “I go around preaching the Gospel of N-O-T.”

Nurture Partnerships in All Project Phases, Especially Around Trust

The cornerstone of our effort hinged on trust and other identified partnership values. We learned that trust is not a word but a way of being. Trust also is based more on researcher actions than on words. Open verbal and nonverbal communication and delivering on promises begin the foundation of trust. Moreover, all partners must be willing to have frank discussions about topics such as race, oppression by the dominant culture, and power. Critically, trust is not something that is not earned once and then left unattended or assumed complete. Trust has to be nurtured, continually nourished, and revisited by both researchers and community partners.

Integrate the Cultural Knowledge of the Community

CBPR principles helped us to learn that life for many NC American Indian people is “a walk in two worlds”—the world of the dominant culture (that is, the “White man’s world”) and the Native world. Related to tobacco, Native communities and their youth are confronted with targeted marketing campaigns that seek to promote the consumption of commercial tobacco products. One community member noted, “I face every day with the challenge of keeping my ‘Indianness.’ I live and work in a world that can take that from me. I need to remember who I am.” It is essential to understand that many American Indian communities battle to keep their culture and traditions intact and untainted by the dominant society.

Produce Beneficial Tools and Products

Tailored programs, such as AI N-O-T, must be developed by and with the community of identity. Moreover, because producing effective and beneficial products requires research, partner discussions must foster new views and definitions of research, including CBPR principles. CBPR strategies increase the existence of culturally competent services and, in turn, increase the likelihood of implementation and effectiveness.

Build Capacity Through Co-Learning and Empowerment

Partners must create opportunities for sharing knowledge and information with each other. Furthermore, teaching must be reciprocal at all levels of partnering. Another important part of empowerment is sharing of fiscal resources. It is essential to go beyond traditional research models where the majority of monies and resources are held by academic institutions.

Utilize an Iterative Process of Development

Development of a program, such as AI N-O-T, is an ever-evolving process that requires patience and flexibility. Each stage of development requires participation by community members, which in our case, ranged from youth to tribal leaders. Development is not a process that can be rushed. As noted by Davis and Reid (1999), many American Indians regard time as temporal rather than linear or fixed (as more conventionally used). Plans, timelines, and deadlines for development and completion may need to be revisited many times and must be flexible.

Share Findings and Knowledge With All Partners and the Community

Dissemination, which can be both a process and an outcome, can be accomplished in many formats. As we learned from our experiences, transparency of all findings and products is a pivotal feature of dissemination. That is, if all partners openly discuss and interpret project outcomes, formats for dissemination will be meaningful and relevant to the community. Outcomes should be distributed in multiple formats, including spoken stories, video, flyers, lay reports, community and academic presentations, and scholarly publications. All partners should have roles in dissemination.

CONCLUSION

CBPR principles fostered sound research and meaningful results among a population historically exploited by research. Beyond the project’s quantitative data, the effort resulted in the development of new and successful partnerships, tobacco-addiction intervention programs (e.g., AI N-O-T), tools and resources tailored to community needs, and a multi-tribal interest in educating the youth and communities about tobacco addiction. The community also gained capacity to address the identified problem with greater self-sufficiency via increased grant-writing skills, evaluation knowledge, tobacco education, and financial resources. The emerging partnerships and resources offer a foundation and beginning for the NC American Indian community to better address the needs of their people. The end of the pilot research phase seems in many ways to only be the beginning of the initiative. One tribal officer summed up our efforts as follows: “And we did this up here in Tobacco Country.”

Acknowledgments

Special appreciation is extended to research team members who worked hand-in-hand with the community across all project phases: Tim McGloin, MPH; Karen Manzo, MPH; Lynn Lowry-Chavis, MPH; Lawrence Shorty, MPH; Greg Richardson; and Reverend Bruce Swett. The authors also thank the following tribes and associations who participated on our advisory board, recruited for and participated in focus groups, contributed to program development, recruited schools and youth, delivered the program, and helped to interpret pilot study findings: Coharie, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, Occaneechi Saponi, Sappony, Waccamaw-Siouan, Cumberland County Association for Indian People, Guilford Native American Association, Metrolina Native American Association, and Triangle Native American Society. Appreciation is also extended to Dr. Lawrence W. Green, Dr. Shawna L. Mercer, and Dr. Cheryl Healton for their tireless efforts to promote and align resources with community-based participatory research (CBPR) at local, state, and federal levels. Funding for this project was provided by the American Legacy Foundation (Grant No. S5076) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R06/CCR321438-03).

Contributor Information

Kimberly Horn, West Virginia University, Morgantown..

Lyn McCracken, West Virginia University, Morgantown..

Geri Dino, West Virginia University, Morgantown..

Missy Brayboy, North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs, Raleigh..

References

- American Legacy Foundation (ALF). (2005). Tobacco and the American Indians and Alaska Native community. Research and Publications, Fact Sheet. Retrieved March 30, 2005, from http://www.americanlegacy.org/americanlegacy/skins/alf/home.aspx

- Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA, & Isichei PA (2001). Forging collaborative partnerships to enhance family health: An assessment of strengths and challenges in conducting community-based research. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1997). Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1997. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48, 993–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1998). American Indians and Alaska Natives and Tobacco. Retrieved March 30, 2005, from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/sgr_1998/sgr-min-fs-nat.htm

- Centers for Public Health Research and Training. (2005). A community resource guide for American Indian tobacco prevention education and research. (Available from the first author at the address listed in the Authors’ Note)

- Davis SM, Going SB, Helitzer DL, Teufel NI, Snyder P, Gittelsohn J, et al. (1999). Pathways: A culturally appropriate obesity-prevention program for American Indian schoolchildren. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69, 796–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SM, & Reid R (1999). Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69, 755–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino G, Horn K, Goldcamp J, Fernandes A, & Kalsekar I (2001). A two-year efficacy study of Not On Tobacco in FL: An overview of program successes in changing teen smoking behavior. Preventive Medicine, 33, 600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dino G, Horn K, Zedosky L, & Monaco K (1998). A positive response to teen smoking: Why N-O-T? National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 82, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M, & Roubideaux Y (Eds.). (2001). Promises to keep: Public health policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Doll L, Dino G, Deutsch C, Holmes A, Mills D, & Horn K (2001). Linking research and practice: Two academic-public health collaborations that are working. Health Promotion Practice, 2, 296–300. [Google Scholar]

- Duran BM, & Duran EF (1999). Assessment, program planning, and evaluation in Indian Country: Toward a postcolonial practice In Huff RM & Klein MV (Eds.), Promoting health in multicultural populations: A handbook for practitioners (pp. 292–311). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery D, Sisk-Franco C, & Glover PN (1995). Conflict of tobacco education among American Indians: Traditional practice or health risks? Proceedings of the Ninth World Conference on Tobacco and Health, Paris, France, October 10–14, 1994. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C, Manson SM, & Bergeisen L (1996). American Indian adolescent health In Kagawa-Singer M, Katz PA, Taylor DA, & Vanderryn JHM (Eds.), Health issues for minority adolescents (pp. ?). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Daniel M, & Novick L (2001). Partnerships and coalitions for community-based research. Public Health Reports, 116, 20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green G, & Mercer S (2001). Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? American Journal of Public Health, 91(12), 1926–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, & Catalano RF (1987). The Seattle Social Development Project: Progress report on a longitudinal study. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Healton C, & Nelson K (2004). Reversal of misfortune: Viewing tobacco as a social justice issue. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS (2001, November). American Indian and Alaska Native teen smoking: A review. National Cancer Institute Changing adolescent smoking prevalence (Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 14, NIH Pub. No. 02–5086). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS, Fredericks L, & Kipnis P (1996, October 1). Patient and smoking patterns in northern California American Indian clinics. Urban and rural contrasts. Cancer, 78(7 Suppl.), 1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn K, Dino G, Kalsekar I, & Mody R (2005). The impact of Not On Tobacco on teen smoking cessation: End-of-program evaluation results, 1998–2003. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 640–661. [Google Scholar]

- Horn K, McGloin T, Dino G, Manzo K, Lowry-Chavis L, Shorty L, et al. (2005, October). Quit and reduction rates for a pilot study of the American Indian Not On Tobacco (N-O-T) program. Prev Chronic Dis [Online serial]. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/oct/05_0001.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huff RM, & Klein MV(Eds.). (1999). Promoting health in multicultural populations: A handbook for practitioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]