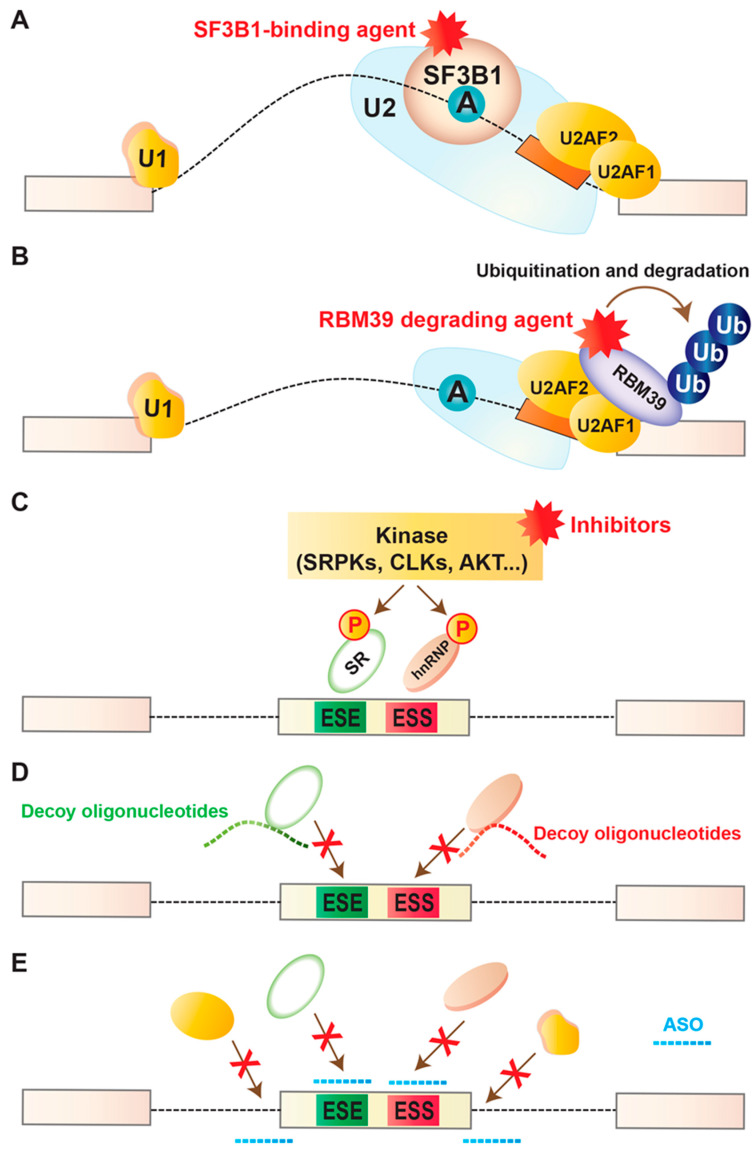

Figure 2.

Therapeutic approaches of splicing modulation in cancer. (A) Pharmacological splicing inhibition using drugs that physically bind to the SF3B complex and disrupt its ability to recognize the branchpoint within the intron. See Table 2 for representative examples. (B) Anticancer sulfonamide compounds promote degradation of RBM39. These compounds physically connect RBM39 to the DCAF15-CUL4 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in ubiquitinylation of RBM39. This subsequently promotes proteasomal degradation of RBM39. See Table 2 for representative examples. (C) Pharmacological inhibition of post-translational modifications using drugs that interfere with the functions of several enzymes, including SR protein kinase family (SRPK), CDC2-like kinases (CLKs), and AKT kinases. See Table 2 for representative examples. (D) Decoy oligonucleotides containing short repeats of RNA-binding motifs can inhibit the function of specific splicing factor by sequestering them and prohibiting binding to the target transcript(s). One representative example was the transfection of specific decoy oligonucleotides into cancer cells targeting SRSF1-binding which resulted in changes in splicing of known targets of SRSF1, including MKNK2 [134]. This subsequently activated the p38–MAPK stress pathway and inhibited the proliferation and survival of cancer cells [134]. (E) Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) can bind to splicing regulatory sequences or motifs in a targeted transcript, and switch splicing to a favorable isoform. One representative example was specific ASOs targeting a poison exon of BRD9 in SF3B1-mutant cells, which showed satisfactory results in splicing modulation and suppressing tumor growth [62].