Abstract

In China, the corresponding control directives for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have been based on primary emissions, rarely considering reactive speciation. To seek more effective VOCs control strategies, we investigated 107 VOC species in a typical coastal city (Beihai) of South China, from August to November 2018. Meanwhile, a high-resolution anthropogenic VOCs monthly emission inventory (EI) was established for 2018. For source apportionments (SAs) reliability, comparisons of source structures derived from positive matrix factorization (PMF) and EI were made mainly in terms of reaction losses, uncertainties and specific ratios. Finally, for the source–end control, a comprehensive reactivity control index (RCI) was established by combing SAs with reactive speciation profiles. Ambient measurements showed that the average concentration of VOCs was 26.38 ppbv, dominated by alkanes (36.7%) and oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) (29.4%). VOC reactivity was estimated using ozone formation potential (52.35 ppbv) and propylene-equivalent concentration (4.22 ppbv). EI results displayed that the entire VOC, OFP, and propylene-equivalent emissions were 40.98 Gg, 67.98 Gg, and 105.93 Gg, respectively. Comparisons of source structures indicated that VOC SAs agreed within ±100% between two perspectives. Both PMF and EI results showed that petrochemical industry (24.0% and 33.0%), food processing and associated combustion (19.1% and 29.2%) were the significant contributors of anthropogenic VOCs, followed by other industrial processes (22.2% and 13.3%), transportation (18.9% and 12.0%), and solvent utilization (9.1% and10.5%). Aimed at VOCs abatement according to RCI: for terminal control, fifteen ambient highly reactive species (predominantly alkenes and alkanes) were targeted; for source control, the predominant anthropogenic sources (food industry, solvent usage, petrochemical industry and transportation) and their emitted highly reactive species were determined. Particularly, with low levels of ambient VOC and primary emissions, in this VOC and NOx double-controlled regime, crude disorganized emission from food industry contributed a high RCI.

Keywords: Volatile organic compounds, Emission inventory, Source apportionment, VOCs reactivity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The potential sources of VOCs were identified by PMF model.

-

•

A high-resolution emission inventory was first established in a typical coastal city.

-

•

VOCs reactivity was evaluated by OFP and propylene-equivalent concentration.

-

•

The VOCs RCI was determined based on source apportionments and reactive speciation.

1. Introduction

In recent years, photochemical pollutants predominantly characterized by ground-level ozone, has been plaguing China (Wang et al., 2010). Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), the principal precursors of ozone, play a significant role through tropospheric reaction (Louie et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). The VOCs emitted from a great diversity of anthropogenic and biogenic sources differ considerably (Li et al., 2015). Globally, anthropogenic emissions are relatively lower, but they are most crucial in urbanized areas (Li et al., 2019). Additionally, some VOC species have adverse effects on human health (Janssens-Maenhout et al., 2015). Therefore, it is essential to obtain reliable information of anthropogenic VOCs and to develop strategies for reducing the emissions of VOCs and the production of ozone.

Either addressing ambient VOCs by a receptor model (RM) or the establishment of a high-resolution emission inventory (EI) is used to conduct source apportionments (SAs) (Hui et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). RM is operated generally by the top-down statistics on measured ambient VOCs, while EI is established with the bottom-up primary emission evaluation method. The uncertainty in EI mainly depends on the accuracy of activity levels and regional representativeness of emission factors; while the uncertainty of RM in statistical inferences is controversial, due to the overlap of trace elements in multiple sources, the differences of RMs, the influence of reaction losses of various species and so on (Ling and Guo, 2014; Ou et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2001). But RM and EI still play as synergistic roles in improving the reliability of SAs (Shao et al., 2011). Although great progress has been made in the VOC SAs (An et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2011; Hui et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2013), a high-resolution dynamic EI is rather scarce, and there are still doubts about the reliability of VOCs source structures by EI and RM. It has been increasingly significant to achieve robust SAs by reconciling the inconsistencies between different approaches.

It is essential to scientifically control of VOCs, not only in terms of SAs but also in VOC chemical composition. The current VOC abatement in China is mainly aimed at the primary emissions, rarely taking their reactive speciation into consideration (Li et al., 2018). The air quality analysis during the COVID-19 lockdown by Li et al. (2020) indicates that extreme reductions in primary emissions cannot fully tackle the current air pollution. To effectively tackle air pollution, a developed integrative VOC control by combining reactive speciation and SAs is necessary and urgent.

Unfortunately, distinguished from the developed megalopolis, the VOCs characteristics research in South China has always been a gap (Zhang et al., 2019). With a long-term dominant primary industry, the lack of systematic analysis of VOCs, particularly from disorganized emission sources, has become the main limitation of VOC control in less-developed areas of South China. Beihai, one of the 14 first so-called “coastal open cities” in South China, has consistently good air quality and ranks the forefront in China. The air quality in Beihai probability indicates the future air quality status of Chinese cities, which provides optimistic prospects for future VOC characterizations of Chinese cities. Sources emission reduction during the COVID-19 lockdown has played a significant role in the decrease of PM2.5, NO2 and SO2 concentrations in YRD (Li et al., 2020), and the concentrations of these pollutants were comparable to those of Beihai in recent years (2016–2018). However, ozone did not show any reduction and increased greatly during the COVID-19 lockdown by Li et al. (2020), which was slightly higher than that of Beihai between 2016 and 2018. Will the VOC study in Beihai provide a reference for effective control of ozone precursors to reduce ozone concentrations?

In this study, an integrated VOC measurement-SAs-reactivity approach described in the next section including VOCs and other pollutant observations, potential SAs analyses by positive matrix factorization (PMF) model, a high-resolution monthly EI establishment for five levels of sub-sources, and a developed source–end comprehensive reactivity control index (RCI). This study aims to (1) reveal the concentration, compositions and characteristics of ambient VOCs in Beihai, (2) obtain robust SAs based on the comparisons and reconciling the RM and EI results, (3) comprehensively estimate the reactivity of ambient VOCs and their sources, and (4) to determine a developed VOC source–end integrated RCI for future air pollution control combined with VOC SAs and reactivity profiles. It is expected to provide references for VOC control in developing Chinese cities by exploring VOC characterizations and control strategies in Beihai.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling program and analysis

2.1.1. Study domain and sampling duration

This study was conducted in Beihai, a typical coastal city in Guangxi, with a population of 1.68 million living in an area of 3337 km2 (in 2018). With the long-term dominant industrial structure of the primary industry (Qi, 2015), agricultural and food industries play important roles in Guangxi, as well as Beihai (Liu et al., 2019). Besides livelihood enterprises, a few large petrochemical plants, steel plants and numerous small-scale enterprises constitute the simple industrial structure of Beihai. Furthermore, the characteristics of tourist cities may highlight the contribution of local vehicle exhaust to VOC emissions (Zhang et al., 2019). It is a typical representative of the underdeveloped areas in South China.

Based on the frequency statistics and levels of ozone pollution, temporal variations in VOC emission, and meteorological factors of 2016–2018 (Table S1), we concluded that the late summer and autumn period (from August to November) can basically reflect the year-round ozone conditions in Beihai. To investigate the VOCs concentrations, five sampling locations were established based on automatic air quality monitoring stations, including four national stations (YT, NE, NWL, and BI) and an additional urban station (BJ) (Fig. 1 ). And NWL served as the background monitoring point. Synchronous sampling and analysis were conducted at each site on workdays under fine weather conditions (no rain and low wind speed). For each sampling day, two ambient VOC samples were collected during 9: 00–10:00 and 15:00–16:00, which captured the troughs and peaks of ozone levels based on the photochemical reaction of VOCs in the daytime (Song et al., 2019). All sampling stations are located 30–50 m above the ground. A total of 160 VOC samples were collected across the sampling events.

Fig. 1.

Locations and the prevailing winds of VOC sampling points in this study.

2.1.2. Sampling and chemical analysis

The samples were collected in pre-evacuated stainless steel canisters and subsequently analyzed with the GC–MS/FID system equipped with TH-PKU 300B pre-concentration system. The offline analysis of ambient VOCs is adopted the same procedure used by Zhang et al. (2019) and Simayi et al. (2020), which is described in Supplement Text 1. The correlation coefficient values of the calibration curve for all target compounds were above 99.5% and the relative mean deviation for the target compounds of five parallel samples was within 15%. In total, 107 VOC species were recognized, which were classified into seven categories (29 alkanes, 11 alkenes, acetylene, 18 aromatics, 35 halocarbons, 12 oxygenated volatile organic compounds [OVOCs], and carbon disulfide), and their concentrations were quantified. The concentration, standard deviation, and method detection limit (MDL) of each component are listed in Table S2.

2.2. Source apportionment

2.2.1. Positive matrix factorization

As previous studies, a PMF 5.0 receptor model was established to identify VOC sources in this study (Li et al., 2017; Mousavi et al., 2018; Simayi et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2016). Depending on the mass balance rather than the source component spectrum, the model can be optimized according to the standard deviation of the data. Negative constraint alone is an additional advantage of PMF (Dumanoglu et al., 2014). The mass balance equation of PMF is shown in Eq. (1)

| (1) |

where xij is the concentration of species j in sample i; gik is the concentration of factor k contribution in sample i; fkj is the mass percentage of species j in source k; eij is other factors for species j in sample i and p is the total number of sources.

Based on the uncertainties, the PMF solution minimizes the objective function (Q), shown in Eq. (2)

| (2) |

where uij represents the uncertainty of species j in sample i.

The uncertainty of VOC samples is calculated using Eqs. (3), (4). If the VOC concentration is below the MDL, Eq. (3) is adopted; otherwise, Eq. (4) is adopted.

| (3) |

| (4) |

where MDL is the detection limit. The error fraction can be 5%–20% (Buzcu and Fraser, 2006; Song et al., 2007), and it was set to 10% in this study.

To ensure a good PMF solution, we replaced the data below the MDL with values equal to half the MDL. Species that were not found or below the MDL in more than 25% of the samples were excluded (Guo et al., 2011); otherwise, we replaced the missing data with the geometric mean of the detected concentrations, and set their uncertainties to four times the geometric mean (Wu et al., 2016). Analyzing the PMF running results, all bootstrap runs were performed with correlation coefficient (R2) > 0.8 and almost 98% of the selected species had an absolute scaled residual less than 3, which indicated great observed-predicted correlations.

2.2.2. VOCs emission inventory

EI is recommended to estimate the primary emissions, which involves estimation applying the statistics of activity levels and localized emission factors. VOC emissions of each sub-source were calculated separately with the emission factors approach with the Eq. (5)

| (5) |

where E n refers to total emission for emission source n; EF n, m refers to the emission factor for mth of source n; A n, m refers to the activity levels for mth of source n and η n, m refers to VOCs control efficiency for mth of source n.

A comprehensive high-resolution classification EI of Beihai was first established based on emission factors and local activity level data in 2018. Specifically, emission factors were obtained from the corresponding EI Guidebooks, reports, and industrial empirical parameters (Table S4). The activity data mainly derived from field investigation and tabulating survey, others were supplemented from the corresponding Environmental Statistics, Yearbook and official bulletins. The survey data were derived from nearly 20 government departments and organizations, and nearly 600 industries related to VOC emissions have been examined in Beihai. Major emission sources, including coal plants, burning boilers and kilns, the petrochemical industry, motor vehicles, shipping, aviation, railway machines, raw chemical manufacturing factories, and biological emissions, were investigated in detail. Additional explanation for the sources and types of activity date using in VOC emission inventory is described in Supplement Text 2. The year-round activity level data and monthly uneven coefficient of five level sub-sources are listed in Table S5.

2.3. Evaluation of VOCs chemical reactivity

VOCs chemical reactivity is not proportional to their concentrations, which exhibits a wide range and act as another important distinguishing characteristic of VOC species. The highly reactive species degrade rapidly, while the less reactive ones are relatively stable, increasing VOC accumulation and exaggerating the potential VOC sources contribution (Ou et al., 2018). In this study, to adequately estimated the chemical reactivity of VOCs, the OH reactivity and ozone formation potential (OFP) were of particular concern. Here, OH reactivity level was normalized by propylene-equivalent (propy-equiv) concentration, which was evaluated by the Eq. (6) (Goldan, 2004; Wu et al., 2016).

| (6) |

where conc i represents the concentration for VOC species i; and denote the reaction rate constant with OH radicals for VOC species i and propylene, derived from Atkinson and Arey (2003) (see Table S2).

Based on the maximum incremental reactivity (MIR) factor, OFP was often used to evaluate the contribution of ambient VOCs to ozone formation (Chang et al., 2005; Vizuete et al., 2008). Referring to the series of MIR values updated by Carter (2010) (see Table S2), OFPs were calculated based on the Eq. (7)

| (7) |

where OFPi is the OFP for VOC species i and MIRi is the MIR for VOC species i.

Then a balanced reactivity control index (RCI) was defined as the Eq. (8), based on normalized index.

| (8) |

where RCIi is the normalized reactivity control index of VOC species i; k is the weight, and k 1 and k 2 were set to 0.5 in this study; Propy − equiv Min and Propy − equiv Max are the minimum and maximum Propy − equiv i among VOC species. OFPMin and OFPMax are the minimum and maximum OFPi among VOC species.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characteristics of VOCs, NOx, CO and ozone

3.1.1. Characteristics and spatiotemporal variations of VOCs

The VOCs concentration ranged from 6.62 to 165.38 ppbv (the abnormally high values that were higher than the 98th percentile of all observed concentrations were excluded in all analysis), with an average of 26.38 ppbv. According to the comparisons of VOCs in Beihai and other areas (Table S3), local VOCs concentration was lower than that in overwhelming majority of cities, comparable to that in Guilin (23.67 ppbv), higher than that in the background sites (Dinghu Mountain and Gongga Mountain). The average composition of VOCs in Beihai was dominated by alkanes (9.69 ppbv) and OVOCs (7.75 ppbv), accounting for 36.7% and 29.4%,respectively. Halocarbons (4.67 ppbv), alkenes (1.50 ppbv) and aromatics (1.47 ppbv) have lower concentrations, followed by alkyne (1.00 ppbv) and carbon disulfide (0.29 ppbv). The proportion of halocarbons (17.7%) in Beihai was higher than Guilin (5.7%), Shanghai (14.0%), Beijing (9.0%), Chengdu (10.4%), and Wuhan (10.8%), except Gongga Mountain (21.6%); while that of aromatics (5.6%) was lower than all listed cities and sites (9.3–65.7%) in Table S3 (Hui et al., 2018; Simayi et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2014). For the most abundant species in Beihai, acetone (5.84 ppbv) was comparable to that in Chengdu (Simayi et al., 2020), much higher than other cities. In general, the short-chain alkanes contributed higher concentrations, and isopentane (2.09 ppbv) was the most abundant alkanes in Beihai, followed by several C2–C4 alkanes (above 1 ppbv). Additionally, 1,2-dichloropropane (0.92 ppbv), dichloromethane (0.91 ppbv), and toluene (0.57ppbv) were the common halocarbons and aromatic. The concentration of each VOC species is listed in Table S2, and the comparisons of VOCs concentration, compositions and top 10 species with other areas are summarized in Table S3.

As shown in Fig. 2 , the temporal variations of VOCs showed a clear monthly dependence with highest in October (33.48 ppbv) and lowest in August (15.31ppbv). This temporal dependence was consistent with alkanes, halocarbons, alkyne, and aromatics, but OVOCs and alkenes displayed highest concentration in November. It is likely due to the temporal variations of source emissions and atmospheric photochemistry of VOCs categories. On the whole, the spatial distributions of VOCs displayed a hotspot in north and southeast areas. The VOCs level at YT was the lowest and lower than the background point (NWL). The low spatial trend of VOCs in western coastal areas was likely related with clean air from South China Sea and weaker emissions nearby. The dominant VOC categories at different sites were consistent, namely alkanes, OVOCs, and halocarbons. The monthly fluctuations of VOC relative to NWL were shown in Fig. 2b. For all the points, the monthly fluctuations of alkanes were the most obvious, followed by halocarbons and aromatics at BI. In particular, with higher contributions in Beihai compared with other cities mentioned above, halocarbons were also pronounced in the background point (NWL,14.7%), exhibiting much higher concentrations (3.22 ppbv) than that in Guilin (1.35 ppbv), an inland city in the same region (Zhang et al., 2019), but the proportion of halocarbons in Beihai (17.7%) was lower than that in two coastal cities of western Canada (18.1% and 37.2%) by Xiong et al. (2020). They are likely to be affected by offshore winds from South China Sea, given the marine environment is a significant natural source of halocarbons and other VOCs (Chuck et al., 2005). Combined with prevailing winds during the sampling period (Fig. 1), concentration of halocarbons in BI was 2–3 times that in other monitoring locations, reaching a high value of 16.8 ppbv in October with a low wind speed (1.4 m/s) from the land; while halocarbons in YT and NE remained at slightly low concentrations, both sites particularly affected by the offshore winds. Therefore, the spatial differences on halocarbons were more related to spatial variations of local anthropogenic emissions. Many studies on VOC SAs revealed that industrial processes and solvent usage are the predominant sources of halocarbons and OVOCs (Mo et al., 2017; Ou et al., 2018; Simayi et al., 2020). Thus, the abundant OVOCs (predominantly acetone) and halocarbons may be correlated with the local industries emission and solvent utilization. Although some variations were observed, the average VOCs concentration can be considered to reflect the annual baseline level of Beihai.

Fig. 2.

Temporal and spatial variations of ambient VOCs in Beihai.

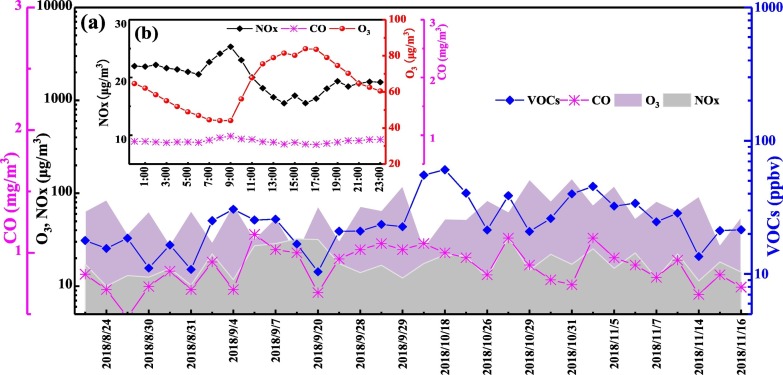

3.1.2. Correlations between air pollutants and VOC/NOx ratios

The average concentrations of O3, NOx, and CO during the study period were 67.08, 19.89, and 890 μg/m3, respectively. The concentration of NOx was lower than that in many cities (Zhang et al., 2019). For the diurnal variation of secondary pollution, O3 revealed a signal peak tendency with minimum and maximum concentrations appearing at 8:00–9:00 and 14:00–16:00, probably affected by solar radiation variations during daytime (Fig. 3 ). For the diurnal variations of ozone precursors, NOx showed the opposite tendency and bimodal tendency, corresponding to morning and evening traffic peak; VOCs concentration generally decreased during the intense photochemical reactions about 15:00. However, the VOCs concentration at 15:00 was higher than 9:00 in several sampling days, especially in September and October. This was likely due to the diurnal accumulation of VOC emissions during the annual peak production period. Similar diurnal variations of NOx were observed, but the occurrence days were not fully synchronized with VOCs. Moreover, associations between VOCs and other air pollutants are shown in Table S6. A weak positive correlation between VOCs and NOx was performed (rs = 0.100). These results implied that there were some differences between the sources of NOx and VOCs. O3 was observed a significantly negative correlation with NOx (rs = −0.264, p < 0.01) and a weak correlation with VOCs (rs = −0.026). The temporal variations of O3 and VOCs showed obviously consistent, with the highest and lowest concentrations in October and August. However, the NOx concentrations decreased slightly in October. A moderate positive correlation between VOCs and PM2.5 (rs = 0.255, p < 0.01) revealed that VOCs may contribute to PM2.5 generation (Han et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). CO as a tracer of vehicle exhaust, its significantly correlations with VOCs (p < 0.05) and NOx (p < 0.01) reflected the obvious effects of vehicle emission on ambient ozone precursors (Luo et al., 2010). The average VOC (ppbC)/NOx ratio (8.38:1) was closed the approximately threshold (8:1) of the transition from VOC-limited to NOx-limited regime (Seinfeld, 1989). In August and September, VOC/NOx ratios were approximately 7:1, indicating the VOC-limited formation in early autumn. Therefore, in this city with lower concentrations of ozone precursors, ozone formation was more likely to be double-controlled by VOC and NOx.

Fig. 3.

Time series concentrations (a) and average diurnal variations (b) of NOx, CO, O3 and VOCs.

3.2. Source apportionments and comparisons of RM and EI

3.2.1. Source apportionments by PMF

Considering the typical tracer species, high concentration species, and reactive identification species, 80 VOC species were selected to input PMF models, accounting for more than 90% of the VOC concentration. Eight factors resolved by PMF respectively were transportation, petrochemical industry, food industry and combustion, other industrial processes, biogenic emissions, fuel evaporation, solvent utilization 1–2, which are summarized in Fig. 4 . Their source profiles are listed in Table S7.

Fig. 4.

VOC source profiles and source emission contributions derived from the PMF model.

Based on the PMF-resolved results, transportation, other industrial processes, biogenic emissions, and fuel evaporation contributed 16.3%, 19.1%, 13.7%, and 4.6%, respectively. Their identification is described in Supplement Text 3, and other three regional special sources are detailed below.

In factor 2, the petrochemical industry was identified by abundant C2–C4 alkanes, C2–C3 alkenes, ethyne and aromatics, correspond with the emission compositions of refinery and petrochemical processing (Buzcu and Fraser, 2006). Additionally, 1,2-dichloroethane (67.8%) was dominated in this factor, which is also a significant symbol of the petrochemical industry (Dumanoglu et al., 2014), followed by 1,2-dichloropropane (65.3%), and methylene chloride (60.5%). Petrochemical industry, a significant industrial VOC emission source in Beihai, was identified as an independent source, contributing highest (20.7%) to VOCs.

Factor 3 had a higher contribution (16.5%) to VOCs, dominated by higher percentages ethene (61.8%), propane (54.5%), propene (50.1%), acetylene (47.9%), n-butane (41.0%), i-butane (37.0%) and some aromatics. VOCs emitted from coal-fired boilers are usually composed of acetylene, C2–C4 alkanes and alkenes (Liu et al., 2008). Generally regarded to be a typical trace of biomass burning (Liu et al., 2008), chloromethane also had a small proportion (2.1%) in this source profile. Thus, the profile was similar to combustion, but the proportion of butane (11.4%) in this factor was higher than that in combustion profiles (2–3%) by Wu and Xie (2017). In the EI of Beihai, combustion only occupies a small part, which is mostly served for food processing with abundant butane disorganized emission (Wu and Xie, 2017). Therefore, this factor was primarily attributed to food processing and related fuel combustion.

Solvent utilization was identified in factors 7 and 8. The former was because of high fractions of aromatics (predominantly BTEX), which was distinguished as solvent usage in coating/painting (Cai et al., 2010; Hui et al., 2018; Ling et al., 2011); the latter was explained by more than 60% of OVOCs, especially abundant acetone (38.2%) and 2-propanol (19.9%). Previous studies suggested that acetone was mainly emitted from industrial solvents and household solvents (Ou et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2013), and 2-butanone was related to the pharmaceutical utilization (Simayi et al., 2020). They were merged into “solvent utilization”, with a total contribution of 9.1%.

3.2.2. VOCs emission inventory

To obtain more reliable SAs by comparative analysis, we also investigated the EIs to estimate the primary VOC emissions. As shown in Fig. 5 , since the petrochemical industry and food industry were separated from industrial processes, anthropogenic VOC sources were subdivided into eight categories. The total anthropogenic VOC emissions of Beihai in 2018 were 40.98 Gg. Particularly, petrochemical industry (33.0%) was the largest anthropogenic contributor, due to highlighted contribution of several leading industrial conglomerates in this small touristy and non-industrial city. The second greatest contributor was food industry (24.9%), comparable to that of Guangxi (23.6%), but much higher than other cities (Liu et al., 2019). Other industrial processes accounted for 13.3%, dominated by synthetic product manufacturing and metal smelting. Transportation made a higher contribution (12.0%), with a significant contribution (48.4%) from gasoline/diesel passenger cars. Next was solvent utilization (9.1%), dominated by roadwork (60.8%). Fossil fuel combustion (3.4%) and biomass burning (0.9%) contributed small. The contribution of storage and transport (3.4%) was higher than in other areas (2%–3%) by Ou et al. (2015).

Fig. 5.

Emissions and contributions of anthropogenic VOC sources (a) and sub-sources (b) in Beihai, 2018.

Large scale enterprises are concentrated in the Tieshangang area, including several large petrochemical and steel plants, as well as Beihai power plant, which may be the main reason of the high VOCs concentration in BJ and northern areas. Food processing enterprises are scattered, and industrial emissions have a greater impact on BI. From Fig. 5a, the average SAs during the VOC sampling period can basically reflect the annual relative emission intensity of VOC sources. For the temporal variations, the contribution of transportation increased significantly in October due to the higher traffic flow during National Day. The food industry contributed highest (40.3% in November) in the hot periods (winter and November) of sugar production. Meanwhile, the bagasse burning enhanced the contribution of biomass burning, but it remained low (1.5% in November). The emissions and monthly contribution coefficients of sources are detailed in Fig. S1. Additionally, the corresponding statistics data of five level sub-sources is listed in Tables S4–S5.

3.2.3. Comparisons of the source structures between RM and EI

In Fig. 6 , the source structures of anthropogenic VOC sources resolved by PMF were compared to that of annual EI. Petrochemical industry contributed the largest to anthropogenic VOCs in both EI and RM, but its proportion in EI (33.0%) was slightly higher than that in RM (24.0%). Similar differences on the food processing and associated combustion between EI (29.2%) and RM (19.1%) were more obvious. They were consistent with the combustion divergences for the city-center of Chengdu from EI (17.9–59.4%) and RM (12.1–31.0%) by Simayi et al. (2020). These divergences probably attribute to their active components, such as C2–C4 alkenes and alkyne, which are removed instantly by atmospheric oxidation (Buzcu and Fraser, 2006). As illustrated in Eqs. (9), (9), (10), (11), (12), (13), the chemical losses of highly reactive light olefins reduce the source contributions resolved by PMF (Derwent et al., 2001). But the divergence on the SAs of petrochemical industry was smaller, due to great amounts of inactive alkanes and halocarbons also in petrochemical source profiles. Long-lived inactive components tend to accumulate in the atmosphere (Gouw et al., 2005), which maybe overestimate the relevant source contributions by PMF. This is one possibility for the SA divergences of other industrial processes between EI (13.3%) and RM (22.2%). The incomplete statistics of other industries may also enhance the underestimation of this source proportion in EI (Ou et al., 2018). However, given there is no heating system in Beihai with an average annual temperature of 22.8 °C between 2016 and 2018, always neglected heating consumption in the EIs has little impact on Beihai (Simayi et al., 2020).

| (9) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Fig. 6.

Comparisons of anthropogenic VOCs source structures between RM and EI.

The contribution of transportation with both methods was comparable and significant. The ratios of T/B (1.52) were close to 2, which indicated that vehicle emission is dominant in Beihai (Garzón et al., 2015). However, the contribution of transportation to EI (12.0%) was slightly lower than that from RM (18.9%). It is worthwhile to note that the kinds of VOCs by measurement in the study (107) have a certain difference with those in EI (152) (Simayi et al., 2020; Wu and Xie, 2017). Individual aldehydes (predominantly formaldehyde and acetaldehyde) were not detected in Beihai and Guilin (Zhang et al., 2019), which mainly emitted from diesel machinery, biomass combustion and cooking by Wu and Xie (2017), accounting for only 1–2% in EI of Beihai. Variations from these carbonyl compounds have little effect on the discrepancies of transportation in the EI and RM in the study area. Liu et al. (2015) emphasized that VOC emission of fuel volatilization from vehicles is often a missing yet significant part in the current EIs. Considering a high-resolution EI of transportation was established based on the detailed date on five emission levels through the field investigation and statistics (Table S5), the underestimation of the source contribution of transportation in EI can be explained by vehicular evaporation emissions, which was excluded in primary source emission statistics, but shown in the PMF results.

The contribution of solvent utilization to EI (9.1%) was comparable to that from RM (10.5%). The low contribution of solvent utilization was consistent with low level ambient aromatics in Beihai. Moreover, the SAs of solvent utilization were both lower than that in Chengdu (26–27%) by Simayi et al. (2020). These results indicated the SA of solvent utilization in Beihai is low, especially from industrial solvent.

Last but not least, compared to other cities, quite high ratios of X/E (1.61) were observed, suggesting little aging air mass and a lower exposure to the long-distance pollution sources (Garzón et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). The secondary and aging air masses were excluded from EI, which also was not identified by PMF in this study. Overall, although there are little differences between RM and EI, the source structures with two methods achieve good consistencies. Furthermore, addressing the impacts of chemical losses by using RMs, obtaining detailed source separation characteristics and supplementing emissions from missing sub-sources will contribute to reconcile the SAs discrepancies between EI and RM. The ratios of T/B and X/E are showed in Fig. S2.

3.3. Improving control strategies for ambient VOCs and their sources

3.3.1. Ambient VOCs reactivity and reactivity control index (RCI)

As shown in Fig. 7 , the OFP and propy-equiv concentrations were 52.35 ppbv and 4.22 ppbv, respectively. Although alkene concentrations were lower compared to alkanes, their high reactivity made the largest contribution to ozone formation (30.3%) and propy-equiv concentration (44.1%), confirmed by previous research (Hui et al., 2018; Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). Except for OVOCs, the propy-equiv concentration showed a strong consistency with OFP (rs = 0.986, p < 0.01), indicating significant correlations between the OH reactivity and ozone formation of VOCs (Hui et al., 2018). As a VOC group with the highest concentration and higher average MIR values (~3.47), OVOCs occupied a more significant proportion to OFP (22.5%) than propy-equiv concentration (2.4%). Additionally, alkanes and aromatics contributed 21.6% and 17.4% to OFP, and their contributions to propy-equiv concentration accounted for 30.2% and 23.3 separately. However, both the OH reactivity and OFP of halocarbons were low, mainly due to the strong chemical bonds within the halocarbons (Ou et al., 2018). The species reactivity based on OH reactivity and OFP was not completely consistent. From the top 10 species based on different scales (Fig. 7), although isoprene concentration was relatively low, it ranked at first (23.0%) and fourth (5.1%) in the OH reactivity and OFP, respectively; while ethene contributed the largest to OFP (14.8%), but it contributed little to OH reactivity (6.6%). This is because that propy-equiv method is mainly focused on kinetic activity and probably overestimates the species (like isoprene) with a faster OH reaction rate, while the MIR method is focused on the mechanism reactivity (Zou et al., 2015).

Fig. 7.

VOC levels and top 10 species based on different scales in Beihai.

Therefore, VOC reactivity was balanced by equivalent weights for both MIR and propy-equiv methods using Eq. (8). According to the VOCs RCI, 107 ambient VOCs were classified to five control levels (Table S7), and these fifteen VOCs in level I (isoprene, ethene, isopentane, 2-butanone and propene) and level II (toluene, i-butane, m/p-xylene, n-pentane, acetone, n-butane, trans-1,3-dichloropropylene, acrolein, 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene and styrene) were selected as active ambient species. The terminal control focused on the reactive VOCs (especially level I species) is more targeted to effectively reduce the formation of ozone. Meanwhile, with respect to the VOC abatement, the reactive VOC sources also need to be considered.

3.3.2. VOC sources control combined source apportionment and reactivity

By combining the VOC SAs with the chemical reactivity of VOC species, we attempted to develop a comprehensive index for VOC sources control. Based on the profiles of each source resolved by the PMF and EI results, the OFP and propy-equiv annual emissions of VOC sources were 67.98 Gg and 105.93 Gg, respectively. Then, a normalized source RCI was determined by equivalently weighing OFP and propy-equiv concentration. Control index based on two scales (CI and RCI) of VOC sources and each VOC source RCI profile are illustrated in Fig. 8 . And the RCI of sub-sources is listed in Table S10, as well as their CI. Just considering the VOC emissions, the CI of petrochemical industry was ranked first except in winter. However, taking species reactivity into consideration, the RCI of food industry and corresponding combustion was the most dominant, especially in autumn and winter (RCI accounting for ~50%), and the emission abatement of its reactive species (i.e., C2–C4 alkenes and C4–C6 alkanes) is crucial. Additionally, the RCI (0.37) of solvent utilization was also dominant, attributed to the abundant highly reactive aromatics and a few alkenes. Meanwhile, the significance of transportation emissions (RCI = 0.27) cannot be ignored, especially from C4–C5 alkanes. The RCI (0.09) of other industrial processes was small, and some attention should be paid to synthetic product and leather manufacturing, as well as metal smelting. In brief, policies to reduce anthropogenic VOC emissions should be mainly aimed at food industry and corresponding combustion by boilers and kilns, solvent usage, petrochemical industry and transportation, and in particular on their highly reactive species (see Tables S9–S10).

Fig. 8.

Control index based on two scales (a) and RCI profiles (b) of VOC sources.

4. Conclusions

In this study, 107 ambient VOCs were continuously measured and their characteristics were explored for the first time in Beihai, providing optimistic prospects for future VOC characterizations of Chinese cities. The correlations between air pollutants and VOC (ppbC)/NOx ratio (8.38:1) revealed ozone formation was more likely to be double-controlled by VOC and NOx in this city with low levels of ozone precursors.

Meanwhile, both SAs and VOC reactivity were synthetically analyzed based on different methods to develop strategies for optimal control of VOC sources and reactive species. SAs were estimated from different perspectives: seven potential sources were identified with the PMF model, and a high-resolution monthly dynamic EI with eight sources (five level sub-sources) was established. Furthermore, robust SAs were obtained by comparing and reconciling the differences of two approaches in terms of chemical reactivity of species, reaction losses, uncertainties, pollutant transmission, T/B and X/E and so on. Both EI and RM results indicated that petrochemical industry, food industry and transportation were significant contributors.

The reactivity of ambient VOCs and sources was evaluated by both MIR and propy-equiv methods. These results by two methods were separately normalized and balanced using equivalent weights. Finally, aimed at the source–end control, a comprehensive VOCs abatement policy was suggested: for end control, the ambient VOC reactivity control index (RCI) was determined, and reducing the emissions of those fifteen highly reactive VOCs above mentioned (RCI > 0.25) was more effective; for source control, the predominant anthropogenic sources and their emitted highly reactive VOC species were determined based on SAs and RCI. According to source reactivity, VOCs emission from food industry was the most prominent, which is a significant characteristic in parts of South China. Unorganized emission from the food industry needs to be tightly controlled.

The VOCs characterizations and robust SAs in this study provide scientific support to analyze air quality. The RCI of VOCs source–end control established in this study supplemented the consideration of reactive speciation on the basis of VOC emission intensity, which offers a more scientific reference for effectively control future ozone pollution.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shuang Fu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Meixiu Guo: Investigation, Resources, Project administration. Jinmin Luo: Investigation, Resources, Project administration. Deming Han: Writing - review & editing. Xiaojia Chen: Writing - review & editing. Haohao Jia: Writing - review & editing. Xiaodan Jin: Supervision, Validation. Haoxiang Liao: Investigation. Xin Wang: Investigation. Linping Fan: Investigation. Jinping Cheng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21777094), the Key Special Project of China Institute for Urban Governance, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. SJTU-2019 UGBD-01), and Ministry of Education Key Projects of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research (NO. 17JZD025).

Editor: Pavlos Kassomenos

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140825.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material.

Supplementary tables.

References

- An J., Zhu B., Wang H., Li Y., Lin X., Yang H. Characteristics and source apportionment of VOCs measured in an industrial area of Nanjing, Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 2014;97:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R., Arey J. Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:4605–4638. doi: 10.1021/cr0206420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzcu B., Fraser M.P. Source identification and apportionment of volatile organic compounds in Houston, TX. Atmos. Environ. 2006;40:2385–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C., Geng F., Tie X., Yu Q., An J. Characteristics and source apportionment of VOCs measured in Shanghai, China. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:5005–5014. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.07.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter W.P.L. Development of the SAPRC-07 chemical mechanism. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:5324–5335. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Chen T., Lin C., Yuan C., Liu S. Effects of reactive hydrocarbons on ozone formation in southern Taiwan. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:2867–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuck A.L., Turner S.M., Liss P.S. Oceanic distributions and air–sea fluxes of biogenic halocarbons in the open ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2005;110(C10) doi: 10.1029/2004JC002741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derwent R.G., Jenkin M.E., Saunders S.M., Pilling M.J. Characterization of the reactivities of volatile organic compounds using a master chemical mechanism. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2001;51:699–707. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2001.10464297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumanoglu Y., Kara M., Altiok H., Odabasi M., Elbir T., Bayram A. Spatial and seasonal variation and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in a heavily industrialized region. Atmos. Environ. 2014;98:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.08.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garzón J.P., Huertas J.I., Magaña M., Huertas M.E., Cárdenas B., Watanabe T., Maeda T., Wakamatsu S., Blanco S. Volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere of Mexico City. Atmos. Environ. 2015;119:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldan D.P. Nonmethane hydrocarbon and oxy hydrocarbon measurements during the 2002 New England Air Quality study. J. Geophys. Res. 2004;109:D21309. doi: 10.1029/2003JD004455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gouw J.A.D., Middlebrook A.M., Warneke C., Goldan P.D., Bates T.S. Budget of organic carbon in a polluted atmosphere: results from the New England Air Quality study in 2002. J. Geophys. Res. 2005;110:D16305. doi: 10.1029/2004JD005623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Cheng H.R., Ling Z.H., Louie P.K.K., Ayoko G.A. Which emission sources are responsible for the volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere of Pearl River Delta? J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;188:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Gao S., Fu Q., Cheng J., Chen X., Xu H., Liang S., Zhou Y., Ma Y. Do volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from petrochemical industries affect regional PM2.5? Atmos. Res. 2018;209:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2018.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hui L., Liu X., Tan Q., Feng M., An J., Qu Y., Zhang Y., Jiang M. Characteristics, source apportionment and contribution of VOCs to ozone formation in Wuhan, Central China. Atmos. Environ. 2018;192:55–71. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.08.042B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens-Maenhout G., Crippa M., Guizzardi D., Dentener F., Muntean M., Pouliot G., Keating T., Zhang Q., Kurokawa J., Wankmüller R., Denier Van Der Gon H., Kuenen J.J.P., Klimont Z., Frost G., Darras S., Koffi B., Li M. HTAP_v2.2: a mosaic of regional and global emission grid maps for 2008 and 2010 to study hemispheric transport of air pollution. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:11411–11432. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-11411-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Xie S., Zeng L., Wu R., Li J. Characteristics of volatile organic compounds and their role in ground-level ozone formation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2015;113:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Tian Y., Zhang J., Zuo W., Li H., Li A., Huang D., Liu J., Liu Y., Sun Z., Liu Y. Insight into the roles of worm reactor on wastewater treatment and sludge reduction in anaerobic-anoxic-oxic membrane bioreactor (A2O-MBR): performance and mechanism. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2017;330:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Wei W., Shao X., Nie L., Wang H., Yan X., Zhang R. A comprehensive classification method for VOC emission sources to tackle air pollution based on VOC species reactivity and emission amounts. J. Environ. Sci. 2018;67:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hao Y., Simayi M., Shi Y., Xie S. Verification of anthropogenic VOC emission inventory through ambient measurements and satellite retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019;19:5905–5921. doi: 10.5194/acp-19-5905-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li Q., Huang L., Wang Q., Zhu A., Xu J., Liu Z., Li H., Shi L., Li R., Azari M., Wang Y., Zhang X., Liu Z., Zhu Y., Zhang K., Xue S., Ooi M., Zhang D., Chan A. Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River Delta Region: an insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:139282. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z.H., Guo H. Contribution of VOC sources to photochemical ozone formation and its control policy implication in Hong Kong. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2014;38:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z.H., Guo H., Cheng H.R., Yu Y.F. Sources of ambient volatile organic compounds and their contributions to photochemical ozone formation at a site in the Pearl River Delta, southern China. Environ. Pollut. 2011;159:2310–2319. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Shao M., Fu L., Lu S., Zeng L., Tang D. Source profiles of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) measured in China: part I. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:6247–6260. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.01.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Man H., Tschantz M., Wu Y., He K., Hao J. VOC from vehicular evaporation emissions: status and control strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;49:14424–14431. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Chen Z., Mo Z., Li H., Huang J., Liang G., Jing Y., Junchao Y., Zhang D., Zhang X., Jia Y. Emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from industrial sources and its spatial characteristics in Guangxi. Acta Scientiae Circumstantia. 2019;39:229–242. doi: 10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2018.0366. (in Chinese) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louie P.K.K., Ho J.W.K., Tsang R.C.W., Blake D.R., Lau A.K.H., Yu J.Z., Yuan Z., Wang X., Shao M., Zhong L. VOCs and OVOCs distribution and control policy implications in Pearl River Delta region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2013;76:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.08.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Li Y., Nazaroff W.W. Intake fraction of nonreactive motor vehicle exhaust in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:1913–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z., Shao M., Lu S., Niu H., Zhou M., Sun J. Characterization of non-methane hydrocarbons and their sources in an industrialized coastal city, Yangtze River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;593–594:641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi A., Sowlat M.H., Sioutas C. Diurnal and seasonal trends and source apportionment of redox-active metals in Los Angeles using a novel online metal monitor and positive matrix factorization (PMF) Atmos. Environ. 2018;174:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ou J., Zheng J., Li R., Huang X., Zhong Z., Zhong L., Lin H. Speciated OVOC and VOC emission inventories and their implications for reactivity-based ozone control strategy in the Pearl River Delta region, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;530–531:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou J., Zheng J., Yuan Z., Guan D., Huang Z., Yu F., Shao M., Louie P.K.K. Reconciling discrepancies in the source characterization of VOCs between emission inventories and receptor modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;628–629:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z. Analysis of the characteristics of industrial structure evolution in Guangxi. J. Qinzhou Univ. 2015:54–62. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-8314.2015.02.011. (in Chinese) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld J.H. Urban air pollution: state of the science. Science. 1989;243:745–752. doi: 10.1126/science.243.4892.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M., Huang D.K., Gu D.S., Lu S.H., Wang J.L. Estimates of anthropogenic halocarbon emissions based on its measured ratios relative to CO in the Pearl River Delta. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:1. doi: 10.5194/acpd-11-2949-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simayi M., Shi Y., Xi Z., Li J., Yu X., Liu H., Tan Q., Song D., Zeng L., Lu S., Xie S. Understanding the sources and spatiotemporal characteristics of VOCs in the Chengdu Plain, China, through measurement and emission inventory. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;714 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Shao M., Liu Y., Lu S., Kuster W., Goldan P., Xie S. Source apportionment of ambient volatile organic compounds in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:4348–4353. doi: 10.1021/es0625982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M., Liu X., Zhang Y., Shao M., Lu K., Tan Q., Feng M., Qu Y. Sources and abatement mechanisms of VOCs in southern China. Atmos. Environ. 2019;201:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vizuete W., Kim B., Jeffries H., Kimura Y., Allen D.T., Kioumourtzoglou M., Biton L., Henderson B. Modeling ozone formation from industrial emission events in Houston, Texas. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:7641–7650. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Shao M., Lu S.H., Yuan B., Zhao Y., Wang M., Zhang S.Q., Wu D. Variation of ambient non-methane hydrocarbons in Beijing city in summer 2008. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:5911–5923. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-5911-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Cheng S., Wei W., Zhou Y., Yao S., Zhang H. Characteristics and source apportionment of VOCs in the suburban area of Beijing, China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2016;7:711–724. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2016.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J.G., Chow J.C., Fujita E.M. Review of volatile organic compound source apportionment by chemical mass balance. Atmos. Environ. 2001;35:1567–1584. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00461-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R., Xie S. Spatial distribution of ozone formation in China derived from emissions of speciated volatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:2574–2583. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Yu Y., Sun J., Zhang J., Wang J., Tang G., Wang Y. Characteristics, source apportionment and reactivity of ambient volatile organic compounds at Dinghu Mountain in Guangdong Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;548–549:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Bari M.A., Xing Z., Du K. Ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in two coastal cities in western Canada: spatiotemporal variation, source apportionment, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;706 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Zhong L., Lau A.K.H., Yu J.Z., Louie P.K.K. Volatile organic compounds in the Pearl River Delta: identification of source regions and recommendations for emission-oriented monitoring strategies. Atmos. Environ. 2013;76:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Yuan B., Shao M., Wang X., Lu S., Lu K., Wang M., Chen L., Chang C.C., Liu S.C. Variations of ground-level O3 and its precursors in Beijing in summertime between 2005 and 2011. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014;14:6089–6101. doi: 10.5194/acp-14-6089-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yin Y., Wen J., Huang S., Han D., Chen X., Cheng J. Characteristics, reactivity and source apportionment of ambient volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in a typical tourist city. Atmos. Environ. 2019;215 doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.116898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Yu Y., Mo Z., Zhang Z., Wang X., Yin S., Peng K., Yang Y., Feng X., Cai H. Industrial sector–based volatile organic compound (VOC) source profiles measured in manufacturing facilities in the Pearl River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;456–457:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Deng X.J., Zhu D., Gong D.C., Wang H., Li F., Tan H.B., Deng T., Mai B.R., Liu X.T., Wang B.G. Characteristics of 1 year of observational data of VOCs, NOx and O3 at a suburban site in Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:6625–6636. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-6625-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary tables.