Abstract

Candida species are the 4th leading cause of nosocomial infections in the US affecting both men and women. Since males of many species can be more susceptible to infections than females, we investigated whether male mice were more susceptible to systemic Candida albicans (C. albicans) infection and if sex hormones were responsible for sex-dependent susceptibility to this infection. Non-gonadectomized or gonadectomized mice were supplemented with sustained release 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5αDHT) or 17-β-estradiol (E2) using subcutaneous pellet implantation. Mice were challenged intravenously with 5 × 105C. albicans/mouse seven days after pellet implantation and monitored for survival and weight change. We observed that male mice were more susceptible to systemic C. albicans infection than female mice while gonadectomized male mice were as resistant to the C. albicans infection as female mice. 5αDHT supplementation of gonadectomized female or male mice increased their susceptibility to the yeast infection while E2 supplementation of gonadectomized male mice did not increase their resistance to the infection. Overall, our results strongly suggest that testosterone plays an important role in decreasing resistance to systemic C. albicans infection.

Keywords: Immunology, Microbiology, Pharmaceutical science, Molecular biology, Pathophysiology, Candida albicans, Sex hormones, Gonadectomized mice

Immunology; Microbiology; Pharmaceutical science; Molecular biology; Pathophysiology; Candida albicans; Sex hormones; Gonadectomized mice.

1. Introduction

The yeast Candida albicans (C. albicans) is an opportunistic pathogen residing in the gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts and may cause two major types of infections in humans: superficial infections, such as oral or vaginal candidiasis, and life-threatening systemic infections [1]. Resistance to infection with C. albicans requires efficient innate and adaptive immune responses [2, 3]. When there is a marked decrease in host immune responses, C. albicans causes a more severe systemic infection [4].

It is widely recognized that females are generally more resistant than males to certain microbial infections [5, 6] and sex hormones (testosterone, estrogen, progesterone) are thought to be largely responsible for the differences in immune responses between males and females [7, 8]. Immune cells express estrogen and androgen receptors and thus, sex hormones can play an important role in regulating immune function [9, 10, 11, 12].

In our studies, we used a C. albicans systemic infection as a model system to study sex differences in susceptibility to Candida infection in male and female mice. Although there are several studies investigating the role of estrogen in infections, few have studied the effects of testosterone on infection and no one has investigated the role of testosterone supplementation in gonadectomized male and female mice infected with C. albicans. Our studies have used this approach to help elucidate whether the sex specific hormonal environment plays a role in determining susceptibility to systemic candidiasis.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Animals

C57BL/6 female and male mice (7–8 weeks of age) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or ENVIGO (Indianapolis, IN). C57BL/6 ovariectomized female and orchiectomized male mice (7–8 weeks of age) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and are referred to as gonadectomized animals throughout these studies. The animals were housed in the AALAC certified animal housing facility at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. They were maintained at room temperature with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. Mice were used according to guidelines established by the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona's Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC). ACUC approved the procedures carried out for this project under Animal Protocol Number 13.015.

2.2. Sex hormone treatment

To investigate the role of sex hormones on the resistance of female and male mice to the systemic C. albicans infection, mice were supplemented with 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5αDHT) or 17-β-estradiol (E2) pellets. The 5αDHT, E2 or placebo control pellets were purchased from Innovative Research of America (Sarasota, FL). Pellets were surgically implanted subcutaneously (s.c.) in mice sedated with16 mg/kg of Xylazine, 80 mg/kg of Ketamine in 1X PBS, 200 μL/20 g mouse, intraperitoneally (i.p.). In experiments in which 5αDHT was tested, gonadectomized male or female mice were supplemented with 5, 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT/21 day release pellets. The 5α-DHT dose (5 mg/21 day release pellets) that we used is comparable to 5α-DHT doses used by others [13, 14]. The physiological level of 5α-DHT in intact adult male mice is about 2 ng/ml [15]. In our experiments, similar to others, we supplemented mice with 150–450 ng/ml 5α-DHT. This accounts for the metabolism of 5α-DHT by 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [16]. In experiments in which E2 was tested, gonadectomized male mice were supplemented with 0.09, 0.18, 0.36 or 0.72 mg E2/21 day release pellets. The E2 pellet doses from Innovative Research of America that we used are comparable to E2 pellet doses (0.01–0.5 mg/21 day release pellets) used by others [13, 14, 17, 18]. According to Relloso et al., supplementing mice with 2 μg/mL per day yielded physiological circulating E2 levels in the serum (~256 ± 75 pg/mL) [17]. In all supplementation experiments, groups of male or female mice were implanted with placebo pellets as controls. After the surgery, mice were given acetaminophen (1.3 mg/mL) in the drinking water for 5 days to alleviate pain due to surgery. Mice were monitored daily for signs of distress as described below and all mice recovered without signs of distress the day after the surgery. Figure 1 shows the mouse treatment regimen.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedures for mice implanted with pellets. Seven days before the yeast infection (D -7), mice were implanted subcutaneously (s.c) with sex hormone or placebo pellets. Mice were given acetaminophen (1.3 mg/mL) in the drinking water for 5 days to alleviate pain due to surgery. All mice were challenged with 5 × 105C. albicans cells/mouse (i.v.) on day 0 (D0) and monitored for up to 21 days after the infection for weight and survival.

2.3. Candia albicans preparation and mouse yeast challenge

Candida albicans was prepared as previously described [19, 20]. Mice were challenged with 5 × 106 C. albicans/mL (100 μL/mouse, intravenously (i.v.)) seven days after pellet implantation (2 days after we ceased acetaminophen treatment).

To evaluate the effect of sex hormone pellet implantation on survival and weight loss, mice were observed daily for up to 2–3 weeks after the yeast infection. Weight loss was determined by averaging the weight from all mice (n = 7) within each group and then using the following equation: ((average weight on day post-infection – average weight on day 0)/average weight on day 0)X100. If mice within a group died or had to be euthanized before the conclusion of the study, the weight at the time of death was considered for the remaining days of the study.

All mice were observed daily for symptoms of distress including weight loss (>20%), ability to get up and down, activity level, and hair coat appearance using a scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (severe symptoms) for each parameter. If the mouse had a score of 3 for any symptom or the sum of the highest 3 scores was over 6, the mouse was euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. This work focused on investigating the effects of sex hormones on mouse resistance to systemic C. albicans infection, thus, the disease signs of fungal infection had to be measurable (i.e. weight loss, activity level and mortality).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 8. Statistical significance for survival studies was done using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Correlation analysis for weight loss was done and reported as a two-tailed p-value. The mouse number/experiment was at least 10 mice per group. We limited the numbers to the least number of mice that would still result in statistical significance. The statistical analysis used is specified in each figure legend. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

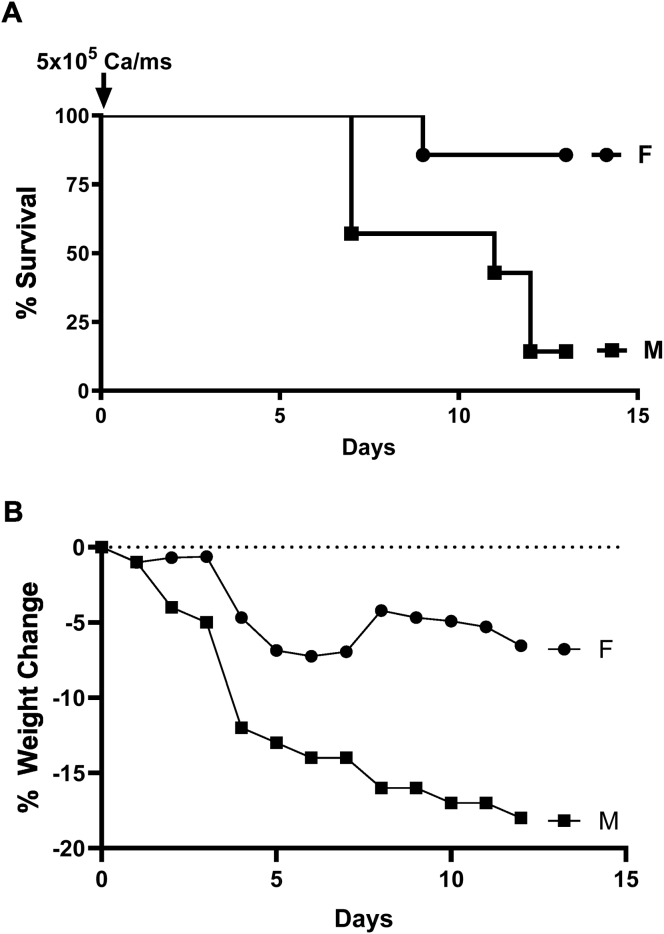

To determine the effect of sex on the susceptibility to systemic C. albicans infection, male and female C57BL/6 mice were challenged i.v. with 5 × 105 C. albicans/mouse, a yeast dose that had been successfully used previously in inducing systemic C. albicans infection in female C57BL/6 mice [20]. As shown in Figure 2A, survival of female mice was significantly greater than that of male mice (86 % survival vs 14% survival, respectively). When comparing mouse weights, male mice lost weight much more readily than females (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of sex on mouse resistance to systemic C. albicans infection. c57BL/6 female and male mice were challenged with 5 × 105C. albicans cells/mouse intravenously (i.v.). The mice (n = 7/group) were observed daily for (A) survival and (B) weight for up to thirteen days. (A) p < 0.02 comparing the survival between female and male mice according to Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (B) p < 0.04 comparing the weight between female and male mice, two-tailed p-value. These results are representative of at least 2 replica experiments.

To determine if the level of mouse organ infection was responsible for the decreased survival of males compared to females, we investigated the number of C. albicans colony forming units (CFU) one, four and seven days after the infection in several organs (kidney, liver, brain) of male and female mice. We did not see a difference in fungal burden in any of these organs between the sexes (data not shown). Therefore, we hypothesize that the higher susceptibility of male mice to the infection is not due to tissue fungal load.

Since others have reported that sex hormones play a significant role in the susceptibility to infections [8, 9], we investigated whether testosterone was responsible for the poor disease outcome in the non-gonadectomized male mice. Testosterone is an intermediate and is converted to E2 by aromatase and to 5αDHT by 5α-reductase [21]. Thus, 5αDHT is the active compound in males. For these studies we first tested the effect of 5αDHT supplementation in gonadectomized female mice. We then examined the effect of 5αDHT supplementation in gonadectomized male mice.

In the first study, gonadectomized female mice were supplemented with 5, 10 or 15 mg/21 day release pellets of 5αDHT. Compared to placebo, gonadectomized female mice supplemented with 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT, but not 5 mg 5αDHT, were more susceptible to the systemic C. albicans infection as assessed by survival (Figure 3A). Survival of gonadectomized females supplemented with 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT was similar to those of non-gonadectomized males (Figure 3A). When comparing mouse weight data, gonadectomized females supplemented with placebo or only 5 mg 5αDHT lost about the same amount of weight (15–18%) by the end of the study (Figure 3C). In comparison, non-gonadectomized males and gonadectomized females supplemented with 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT pellets lost about 24–25% of their initial weight by the end of the study (Figure 3C), indicating that these mice were sicker than gonadectomized female mice supplemented with placebo or only 5 mg 5αDHT.

Figure 3.

Effect of Testosterone supplementation on gonadectomized female and male mouse resistance to systemic C. albicans infection. Seven days before the yeast infection, gonadectomized c57BL/6 female (A,C) and male (B,D) mice (n = 7/group) were implanted (s.c) with 5α-DHT (5–15mg/21 day release pellets) or placebo pellets; female and male mice were implanted (s.c.) with placebo pellets. All mice were challenged with 5 × 105C. albicans cells/mouse (i.v.) on day 0. The mice were observed daily for (A,B) survival and (C,D) weight for up to 21 days after the yeast infection. (A,C) XFP = gonadectomized female mice implanted with placebo; MP = male mice implanted with placebo; XF5-XF15 = gonadectomized female mice implanted with the different doses of 5α-DHT. (B,D) FP = female mice implanted with placebo; MP = male mice implanted with placebo; M15 = male mice implanted with 15 mg 5α-DHT pellets; XMP = gonadectomized male mice implanted with placebo; XM10-XM15 = gonadectomized male mice implanted with the different doses of 5α-DHT. (A) p = 0.05 comparing the survival between XFP and XF10; p = 0.01 comparing the survival between XFP and XF15. All other comparisons with XFP were not statistically significantly different. (C) p < 0.0001 comparing XFP to XF10, XF15 and MP; there were no statistical differences between XFP and XF5. (B) p < 0.02 comparing the survival between FP and MP and p < 0.007 comparing the survival between XMP and M15. All other survival comparisons were not statistically significantly different. The statistical values for survival were obtained according to the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The statistical values for weight were obtained by two-tailed p-value. These results are representative of at least 2 replica experiments.

In the second study using 5αDHT, gonadectomized male mice were supplemented with 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT/21 day release pellets. In addition, some non-gonadectomized males were supplemented with 15 mg 5αDHT/21 day release pellets to increase their androgen levels. Gonadectomized male mice supplemented with placebo were as resistant to the yeast infection as females supplemented with placebo in terms of survival (Figure 3B). Compared to these two groups, non-gonadectomized males with or without 5αDHT supplementation were significantly more susceptible to the infection as assessed by survival (Figure 3B). There was also no significant difference in survival between non-gonadectomized males supplemented with placebo or 5αDHT. Gonadectomized male mice supplemented with 5αDHT trended to be more susceptible to the yeast infection compared to gonadectomized males and females supplemented with placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 3B). When comparing mouse weights amongst all treatment groups, non-gonadectomized female mice supplemented with placebo lost about 10% of their body weight, gonadectomized males supplemented with placebo lost about 14%, gonadectomized male mice supplemented with 10 or 15 mg 5αDHT lost about 19% and non-gonadectomized males with or without 15 mg 5αDHT supplementation lost about 23% of their body weight (Figure 3D). This weight data correlated with the survival outcomes.

To investigate whether female mice were more resistant than male mice to the C. albicans systemic infection because of the female hormone estrogen, we supplemented gonadectomized male mice with E2 (0.09–0.72 mg/21 day release pellets). The non-gonadectomized female and male mouse groups in this experiment were not supplemented with E2 and were only given the placebo pellets. In this E2 supplementation study, gonadectomized male mice supplemented with placebo were as resistant to the yeast infection as female mice given placebo as assessed by survival (Figure 4A) and weight loss (Figure 4B). In comparison, E2 supplementation, at all doses used, worsened the survival of the gonadectomized male mice when compared to females supplemented with placebo (Figure 4A). Non-gonadectomized male mice receiving placebo and gonadectomized male mice supplemented with E2 lost significantly more weight compared to that of gonadectomized male mice and female mice receiving placebo (Figure 4B). A similar result has been previously reported by Relloso et al (2012) in ovariectomized BALB/c female mice given E2 supplementation. In their study, they found that female mice supplemented with E2 had decreased survival and increased tissue fungal load when challenged systemically with C. albicans [17]. Table 1 summarizes the results.

Figure 4.

Effect of Estradiol supplementation on gonadectomized male mouse resistance to systemic C. albicans infection. Seven days before the yeast infection, gonadectomized c57BL/6 male mice (n = 7/group) were implanted (s.c.) with 17β-estradiol (E2) 0.09–0.72mg/21 day release pellets. All mice were challenged with 5 × 105C. albicans cells/mouse (i.v.) on day 0. The mice were observed daily for (A) survival and (B) weight for up to 15 days after the yeast infection. FP = female mice implanted with placebo; MP = male mice implanted with placebo; XMP = gonadectomized male mice implanted with placebo; XM0.09-XM0.72 = gonadectomized male mice implanted with the different doses of E2. (A) p < 0.007 comparing the survival between FP and MP; p < 0.0005 comparing the survival between FP and XM0.09, XM0.18 and XM0.36; p = 0.02 comparing the survival between FP and XM0.72. The statistical values for survival were obtained according to the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (B) There was no statistical significant difference weight loss between FP and any of the other treatments. These results are representative of at least 2 replica experiments.

Table 1.

Results summary.

| Figure # | Observation | Statistical Significance of difference |

|---|---|---|

| 2A | Male mouse survival to systemic C. albicans infection was lower than that of female mouse survival | P < 0.02 |

| 2B | Male mouse weight loss due to systemic C. albicans infection was greater than that of female mouse weight loss | P < 0.04 |

| 2, 3 | Survival and weight loss of orchiectomized male mice was comparable to that of female mouse controls. | ns |

| 3A | Survival of ovariectomized mice supplemented with 5aDHT (10, 15mg/21 days pellets) tended to be lower than that of ovariectomized mouse controls. | p = 0.05 comparing the survival between XFP and XF10; p = 0.01 comparing the survival between XFP and XF15. All other comparisons with XFP were not statistically significantly different. |

| 3B | Survival of orchiectomized mice supplemented with 5aDHT (10, 15mg/21 days pellets) tended to be lower than that of ovariectomized mouse controls. | p < 0.02 comparing the survival between FP and MP and p < 0.007 comparing the survival between XMP and M15. All other survival comparisons were not statistically significantly different. |

| 3C | Weight loss of ovariectomized mice supplemented with 5aDHT (10, 15mg/21 days pellets) tended to be lower than that of ovariectomized mouse controls. | p < 0.0001 comparing XFP to XF10, XF15 and MP; there were no statistical differences between XFP and XF5. |

| 3D | Weight loss of orchiectomized mice supplemented with 5aDHT (10, 15mg/21 days pellets) tended to be lower than that of ovariectomized controls, but was not statistically different. | ns |

| 4A | Survival of orchiectomized mice supplemented with E2 (0.09–0.72mg/21 days pellets) was lower than that of female mouse controls. | p < 0.007 comparing the survival between FP and MP; p < 0.0005 comparing the survival between FP and XM0.09, XM0.18 and XM0.36; p = 0.02 comparing the survival between FP and XM0.72. |

| 4B | Weight loss of orchiectomized mice supplemented with E2 (0.09–0.72mg/21 days pellets) tended to be lower than that of female mouse controls. | ns |

ns = not significant.

It has been reported that C. albicans has an estrogen binding protein which is involved in increasing C. albicans’ virulence because it drives the yeast into a hyphal more virulent state [22, 23]. It is possible that in mice given E2, the virulence of C. albicans increases by driving the yeast to become the more invasive hyphae form. It is not known what effect Testosterone has on C. albicans morphology. We carried out in vitro studies in which we exposed the yeast to different concentrations of E2 or Testosterone for 4h at 37 °C. We found that, compared to non-sex hormone treated yeast, yeast cell number did not change due to sex hormone treatment. We also found that, compared to non-sex hormone treated yeast, cell morphology did not change upon sex hormone treatment. This was not surprising given that C. albicans is known to exhibit a hyphal morphology at temperatures above 35 °C [24].

4. Discussion

C. albicans is one of the leading causes of invasive candidiasis. A longitudinal study based on data obtained from 2012 to 2016 from 22 counties in 4 states within the United States (Georgia, Maryland, Oregon and Tennessee), showed that candidemia is one of the most common types of bloodstream infections in the United States [25]. In this population, 3,492 cases of candidemia were identified. Candidemia occurred in patients who had undergone surgical procedures, patients who had received systemic antibiotics, patients who had a central venous catheter and in individuals who had used injection drugs [25]. C. albicans accounted for 39% of the cases whereas C. glabrata caused 28% and C. parapsilosis 15% of the candidemia [25]. About one in four cases of candidemia result in death [25]. People 65 years of age and older had the highest crude annual incidence followed by infants less than 1 year old. Black people had a higher incidence than non-black people and males had a higher incidence than females [25]. Across species, it is widely recognized that males are less resistant to infections than females, and it has been postulated that sex hormones are largely responsible for this [8, 9].

In our study, we investigated the effect of sex hormone supplementation on the resistance to C. albicans infection in male and female mice. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of E2 and 5αDHT supplementation in male mice infected with C. albicans.

Disparity in male and female mouse resistance to C. albicans infection has been noted previously. In 1972, Rifkind and Frey infected CFW mice with heat-killed C. albicans and measured their agglutinating antibody response. They found that antibody titers of unilateral gonadectomized control females were higher than those of unilateral gonadectomized control males. Bilateral gonadectomy resulted in a significant increase in the antibody titer in males, but did not affect the mean titer in the gonadectomized females [26]. In another study, Rifkind and Frey reported that intraperitoneal injection of viable C. albicans appeared in the urine of about 80% of CFW male and female mice within 2 weeks of inoculation. After 10 weeks, C. albicans persisted in the urine of 37% of males compared to 16% of females. Kidney yeast cultures were present in 53% of males and 25% of females. Gonadectomy prior to infection in both sexes increased the resistance to the infection [27]. In our studies, we also showed that male mice were significantly more susceptible than female mice to a systemic C. albicans infection and that gonadectomy improved the disease outcome of males.

Differences between the sexes include the sex hormones, estrogen and testosterone. To determine if these hormones play a critical role in controlling susceptibility to C. albicans infection, we supplemented gonadectomized mice with sex hormones. We showed that supplementation of mice with 10 or 15mg 5αDHT, but not 5 mg 5αDHT, worsened the disease outcome in gonadectomized female mice, and less so in gonadectomized male mice. It is possible that the 5αDHT supplemental dose given to the gonadectomized male mice was lower than the amount of testosterone normally present in non-gonadectomized mice.

To our knowledge, there is only one other study in which the investigators examined the effect of testosterone supplementation on the resistance to yeast infections. In that study, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, a pathogen that causes a pulmonary infection endemic in Latin America, was used. The infection caused by this fungus is much more prevalent in men than in women. In that study, they found that BALB/c male mice were much more susceptible to P. brasiliensis infections than female mice. They showed that testosterone propionate supplementation of gonadectomized female mice increased susceptibility to P. brasiliensis infection, and that E2 supplementation of castrated males initially restricted yeast proliferation, but that the infection later progressed [28].

In the present study, we showed that E2 worsened the disease outcome in gonadectomized male mice as assessed by survival and weight loss. A possible explanation for this is that relatively high physiological estrogen levels are known to bias the immune response from a Th1 (IFNγ) to a Th2 (IL-4) cell response, and more recently, estrogen has been shown to alter the activity of Th17 and Treg cells. Th17 cells have been shown to be essential in the resistance against C. albicans infection [29]. In some studies, estrogen was shown to enhance Th17 regulated inflammation. In some other studies, estrogen was shown to increase the number of Treg cells, cells that are crucial in downregulating the immune response (reviewed in [30]). As mentioned previously, Relloso et al (2012) found that E2 supplementation of ovariectomized BALB/c female mice impaired their response to a systemic C. albicans infection as assessed by decreased mouse survival and increased tissue fungal load [17]. In their study, they went on to show that E2 treatment diminished the Th17 immune response to C. albicans antigens. Furthermore, Relloso et al (2012) found that E2 impaired dendritic cells’ ability to present C. albicans antigens to T cells thereby reducing polarization of T cells toward a Th17 phenotype. Although we did not test E2 supplementation in our ovariectomized c57BL/6 female mice, this could be investigated in the future to determine if it would decrease the resistance to C. albicans infection in these mice.

Although our studies strongly suggest that 5αDHT suppresses mouse resistance to systemic C. albicans infections, we cannot negate the potential effect of genes present in the X and Y chromosomes. The X chromosome expresses several genes implicated in immunological processes, such as toll-like receptors, multiple cytokine receptors, genes involved in T cell and B cell activity and transcriptional and translational regulatory factors [5]. The Y chromosome also encodes a number of genes involved in inflammatory pathways [5, 9, 31]. Therefore, although sex hormones have an effect on the susceptibility to systemic C. albicans infection, the products of other genes in the sex chromosomes may also be involved.

Future studies should be directed at determining what type of effect 5αDHT has on various immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages and neutrophils, as these are key cells in the immune resistance to C. albicans infections [32, 33, 34]. Discerning the differences in immune responses between females and males is needed as current treatments including drug and vaccination treatments do not generally consider sex-differences [35].

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Melissa Arroyo-Mendoza: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Kristiana Peraza: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments.

Jon Olson: Performed the experiments.

Jill P. Adler-Moore: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Nancy E. Buckley: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant# 5SC3GM087220-04), the Cal Poly Pomona ADVANCE Career Award and the Cal Poly Pomona President's Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Ms. Cynthia Tessler with her assistance with the animal protocol development and submission.

References

- 1.MacCallum D.M., Coste A., Ischer F., Jacobsen M.D., Odds F.C., Sanglard D. Genetic dissection of azole resistance mechanisms in Candida albicans and their validation in a mouse model of disseminated infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(4):1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01645-09. Epub 2010/01/21. PubMed PMID: 20086148; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2849354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S.C., Joosten L.A., Kullberg B.J., Netea M.G. Interplay between Candida albicans and the mammalian innate host defense. Infect. Immun. 2012;80(4):1304–1313. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06146-11. Epub 2012/01/19. PubMed PMID: 22252867; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3318407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vonk A.G., Netea M.G., Kullberg B.J. Phagocytosis and intracellular killing of Candida albicans by murine polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;845:277–287. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8_18. Epub 2012/02/14. PubMed PMID: 22328381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Luca C., Guglielminetti M., Ferrario A., Calabr M., Casari E. Candidemia: species involved, virulence factors and antimycotic susceptibility. New Microbiol. 2012;35(4):459–468. Epub 2012/10/31. PubMed PMID: 23109013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein S.L., Flanagan K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. Epub 2016/08/23. PubMed PMID: 27546235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.vom Steeg L.G., Klein S.L. SeXX matters in infectious disease pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005374. Epub 2016/02/20. PubMed PMID: 26891052; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4759457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein S.L. The effects of hormones on sex differences in infection: from genes to behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000;24(6):627–638. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00027-0. Epub 2000/08/15. PubMed PMID: 10940438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vom Steeg L.G., Klein S.L. Sex steroids mediate bidirectional interactions between hosts and microbes. Horm. Behav. 2017;88:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.10.016. Epub 2016/11/07. PubMed PMID: 27816626; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6530912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giefing-Kroll C., Berger P., Lepperdinger G., Grubeck-Loebenstein B. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell. 2015;14(3):309–321. doi: 10.1111/acel.12326. Epub 2015/02/28. PubMed PMID: 25720438; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4406660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovats S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell. Immunol. 2015;294(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.01.018. Epub 2015/02/16. PubMed PMID: 25682174; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4380804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trigunaite A., Dimo J., Jorgensen T.N. Suppressive effects of androgens on the immune system. Cell. Immunol. 2015;294(2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.02.004. Epub 2015/02/25. PubMed PMID: 25708485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vemuri R., Sylvia K.E., Klein S.L., Forster S.C., Plebanski M., Eri R. The microgenderome revealed: sex differences in bidirectional interactions between the microbiota, hormones, immunity and disease susceptibility. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019;41(2):265–275. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0716-7. Epub 2018/10/10. PubMed PMID: 30298433; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6500089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng X., Buckley D., Klaassen C.D. Regulation of hepatic bile acid transporters Ntcp and Bsep expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;74(11):1665–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.014. Epub 2007/09/28. PubMed PMID: 17897632; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2740811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett B.J., de Aguiar Vallim T.Q., Wang Z., Shih D.M., Meng Y., Gregory J. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metabol. 2013;17(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.011. Epub 2013/01/15. PubMed PMID: 23312283; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3771112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitsch S.M., Wittmann F., Angele P., Wichmann M.W., Hatz R., Hernandez-Richter T. Physiological levels of 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone depress wound immune function and impair wound healing following trauma-hemorrhage. Arch. Surg. 2004;139(2):157–163. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.157. Epub 2004/02/11. PubMed PMID: 14769573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Y., Penning T.M. Steroid 5alpha-reductases and 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: key enzymes in androgen metabolism. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2001;15(1):79–94. doi: 10.1053/beem.2001.0120. Epub 2001/07/27. PubMed PMID: 11469812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Relloso M., Aragoneses-Fenoll L., Lasarte S., Bourgeois C., Romera G., Kuchler K. Estradiol impairs the Th17 immune response against Candida albicans. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;91(1):159–165. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1110645. Epub 2011/10/04. PubMed PMID: 21965175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukai K., Urai T., Asano K., Nakajima Y., Nakatani T. Evaluation of effects of topical estradiol benzoate application on cutaneous wound healing in ovariectomized female mice. PloS One. 2016;11(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163560. Epub 2016/09/23. PubMed PMID: 27658263; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5033238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler-Moore J.P., Olson J.A., Proffitt R.T. Alternative dosing regimens of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) effective in treating murine systemic candidiasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54(6):1096–1102. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh460. Epub 2004/10/29. PubMed PMID: 15509617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumstein G.W., Parsa A., Park A.K., McDowell B.L., Arroyo-Mendoza M., Girguis M. Effect of Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on mouse resistance to systemic Candida albicans infection. PloS One. 2014;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103288. Epub 2014/07/25. PubMed PMID: 25057822; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4110019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randall V.A. Role of 5 alpha-reductase in health and disease. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994;8(2):405–431. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80259-9. Epub 1994/04/01. PubMed PMID: 8092979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priest S.J., Lorenz M.C. Characterization of virulence-related phenotypes in Candida species of the CUG clade. Eukaryot. Cell. 2015;14(9):931–940. doi: 10.1128/EC.00062-15. Epub 2015/07/08. PubMed PMID: 26150417; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4551586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noble S.M., Gianetti B.A., Witchley J.N. Candida albicans cell-type switching and functional plasticity in the mammalian host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15(2):96–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.157. Epub 2016/11/22. PubMed PMID: 27867199; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5957277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadeem S.G., Shafiq A., Hakim S.T., Anjum Y., Kazm S.U. Effect of growth media, pH and temperature on yeast to hyphal transition in Candida albicans open. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;3:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toda M., Williams S.R., Berkow E.L., Farley M.M., Harrison L.H., Bonner L. Population-based active surveillance for culture-confirmed candidemia - four sites, United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(8):1–15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6808a1. Epub 2019/09/27. PubMed PMID: 31557145; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6772189 the submitted work, and William Schaffner reports personal fees from Merck, Pfizer, Dynavax, Seqirus, SutroVax, and Shionogi outside the submitted work. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rifkind D., Frey J.A. Sex difference in antibody response of CFW mice to Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 1972;5(5):695–698. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.695-698.1972. Epub 1972/05/01. PubMed PMID: 4564879; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC422427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rifkind D., Frey J.A. Influence of gonadectomy on Candida albicans urinary tract infection in CFW mice. Infect. Immun. 1972;5(3):332–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.3.332-336.1972. Epub 1972/03/01. PubMed PMID: 4564561; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC422370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aristizabal B.H., Clemons K.V., Cock A.M., Restrepo A., Stevens D.A. Experimental paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection in mice: influence of the hormonal status of the host on tissue responses. Med. Mycol. 2002;40(2):169–178. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.2.169.178. Epub 2002/06/13. PubMed PMID: 12058730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez-Santos N., Gaffen S.L. Th17 cells in immunity to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(5):425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.008. Epub 2012/05/23. PubMed PMID: 22607796; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3358697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan D., Ansar Ahmed S. The immune system is a natural target for estrogen action: opposing effects of estrogen in two prototypical autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2016;6:635. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirandola L., Wade R., Verma R., Pena C., Hosiriluck N., Figueroa J.A. Sex-driven differences in immunological responses: challenges and opportunities for the immunotherapies of the third millennium. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2015;34(2):134–142. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2015.1018417. Epub 2015/04/23. PubMed PMID: 25901858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin Y., Zhang L., Xu Z., Zhang J., Jiang Y.Y., Cao Y. Innate immune cell response upon Candida albicans infection. Virulence. 2016;7(5):512–526. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piliponsky A.M., Acharya M., Shubin N.J. Mast cells in viral, bacterial, and fungal infection immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(12) doi: 10.3390/ijms20122851. Epub 2019/06/20. PubMed PMID: 31212724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Archambault L.S., Trzilova D., Gonia S., Gale C., Wheeler R.T. Intravital imaging reveals divergent cytokine and cellular immune responses to Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis. mBio. 2019;10(3) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00266-19. Epub 2019/05/16. PubMed PMID: 31088918; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6520444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiman S. Immune response to viruses and vaccines differ between men and women. Microbe. 2016;11(9):383–387. [Google Scholar]