Abstract

Wine industry generates a large amount of biowaste, such as grape marc and wine lees, which is considered in the Directive (EU) 2018/2001 as an adequate feedstock to produce advanced biofuels. Grapeseed oil fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) can be obtained from oil extracted from grape marc and bioethanol distilled from wine lees or wine surplus. Although FAEE still has no specific standard, grapeseed oil FAEE would fulfill all of the properties set by the standard EN 14214, except oxidation stability. This work analyzes the effect of natural antioxidants on the oxidation stability of grapeseed oil FAEE, using grapeseed oil fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) as a reference for comparison. On the one hand, the biofuel, produced with conventional transesterification, was mixed with FAME and FAEE produced via in situ transesterification. On the other hand, antioxidants extracted from grapeseed or defatted grapeseed flour were added to the biofuel. The results show that (1) FAEE has worse oxidation stability than FAME, (2) in situ transesterification improves the oxidation stability, and (3) addition of natural antioxidants is hindered by their low solubility in alkyl esters. Finally, the concentration of antioxidants, measured by UV–vis spectroscopy, showed a correlation between the absorbance at 285 nm (characteristic of phenolic compounds) and the induction time (IT) of the samples.

1. Introduction

There is an urgent need to look for environmentally sustainable fuel alternatives faced with the increase in the global concentration of greenhouse gases (mainly CO2), which are causing climate change.1 The use of renewable sources, such as biofuels, can help solve this serious issue, especially if these biofuels are autochthonous and have a residual origin. There are several initiatives all over the world but Europe is leading the way through the Directive (EU) 2018/2001,2 identifying a series of advanced biofuels that mostly have those characteristics. In particular, this directive targets a significant increase in the presence of advanced biofuels with the aim to reach 3.5% of the final energy consumed by 2030 in the transport sector.

The wine industry generates grape marc and wine lees as byproducts (among others), from which grapeseed oil and bioethanol can be obtained, respectively. Both byproducts are included as raw materials that allow to obtain advanced biofuels in the aforementioned directive. These byproducts have great potential in Spain, which has the largest vineyard area (1.0 Mha) in Europe and also in the world.3 In 2018, 77.8 Mt of grapes were produced in the world and Spain was the second country in Europe in grape production (6.9 Mt).3 Moreover, in 2018, 292 MhL of wine were produced in the world, with Spain being the third major wine producer (44.4 MhL) in Europe.3 This huge amount of wine production also involves the generation of a large number of byproducts, as grape marc (15–20% with respect to grape weight) and wine lees (10–15% with respect to grape weight).4 Grape marc is composed of grape skins (70–90% w/w), grape stems (5–20% w/w), and grapeseeds (0.5–2% w/w).5 From the grapeseeds, grapeseed oil can be extracted (13–19% w/w).4 Besides, bioethanol can also be obtained from the wine industry. In Spain, in 2018, 5.2 MhL of bioethanol derived from wine surplus and grape marc, which accounted for 5% of the total bioethanol production.6,7

To use both byproducts (grapeseed oil and surplus bioethanol) from the wine industry, the production and characterization of fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) of grapeseed oil were studied in previous work.8 It was concluded that grapeseed oil FAEE is a biofuel, which, in addition to being completely renewable and derived from residual raw materials, presents very good properties, such as the lower and higher heating values, density, kinematic viscosity, and cold flow properties, all of them within the limits of biodiesel standard EN 14214.9 Only oxidation stability showed values below the minimum limit established in the aforesaid standard.

The mechanism of lipid oxidation is described in three main steps: initiation, propagation, and termination, which produce hydroperoxides and free radicals, the latter tending to form more stable final products of high molecular weight, such as insoluble oxygenated compounds.10−12 The fatty acid structure, the temperature, the light exposure, the storage, and the pro-oxidizing agents are factors that have an influence on the lipid oxidation mechanism. The oxidation products (e.g., acids, insoluble compounds, deposits) can compromise fuel properties, fuel quality, and engine performance,13 reducing the service life of the engine fuel system.14 Exhaust emissions are also altered when oxidized biodiesel is used in a diesel engine.15 Moreover, the oxidized biodiesel can contaminate engine-lubricating oil, reducing its oxidation stability, leading to sludge formation and increasing engine wear, so that engine components such as bearings, seals, or filters, among others, could be affected.16 Thus, an alternative way to slow or diminish the thermal oxidation of FAEE and fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs)17,18 is to incorporate natural antioxidants present in the feedstock, producing biodiesel via in situ transesterification (i.e., using the seeds directly instead of oil)19−22 or dosing conventional biodiesel with natural antioxidants extracted from the feedstock.23 Antioxidants are synthetic compounds, vitamins, minerals, natural pigments, plant components, and enzymes that inactivate the free radicals by donating hydrogen atoms or electrons to these oxidation intermediates. In the biodiesel industry, the more frequently used synthetic antioxidants are butyl-hydroxy-toluene (BHT), butyl-hydroxy-anisole (BHA), tert-butyl-hydroquinone (TBHQ), n-propylgallate (PG), and pyrogallol (PY),11,14 which give a proton from their −OH phenolic group to the fatty free radical, regenerating the fatty ester molecule and cutting the lipid oxidation mechanism. According to Brewer,24 the natural antioxidants avoid the carcinogenic and toxicological effects on humans of the synthetic antioxidants mentioned above. Ascorbic acid, flavonoids, carotenoids, tocopherols, tocotrienols, anthocyanins, and catechins are natural antioxidants present in plants and have a high antioxidant capacity associated with (1) the reactivity of the hydroxyl phenolic group to inactivate the free radicals or the singlet oxygen and (2) the decomposition of peroxides and hydroperoxides into stable oxygenated compounds.25 Tocopherols, tocotrienols, and catechins also inhibit the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids and esters, thus playing an important role against lipid oxidation.26Vitis vinifera grapeseed and grapeseed oil press residues contain between 147 and 1165 mg/kg dry matter of phenolic acids and between 2.52 and 18.78 g/kg dry matter of flavonoids, respectively.27 A 98% (v/v) ethanolic extract of Moringa oleifera increased the oxidative stability (induction time values) of soybean biodiesel from 3.8 to 10.3 h using 100 μg/g of the extract, showing better performance than the synthetic antioxidant TBHQ.28

Grapeseed oil FAEE has been studied by other authors,19 although marginally. Grapeseed oil FAME has been more extensively studied,4,19,29 but this one is not fully renewable due to the use of methanol as the transesterification reagent. Moreover, grapeseed oil FAEE presents a better cetane number,30 cold flow properties,19 heating value,8,19,29 and lubricity8,29,31 than grapeseed oil FAME. However, both alkyl esters present lower oxidation stability19 than that required in EN 14214 and so the search for sustainable alternatives is necessary to obtain environmentally friendly biodiesel. In that order, no references have been found about the production of grapeseed oil FAEE via in situ transesterification, while only Fernández et al.19 tested the in situ transesterification to produce grapeseed oil FAME, highlighting that this biofuel has very good oxidation stability, probably as a consequence of the antioxidant’s extraction from grapeseed.23,32,33 Other in situ transesterifications with different raw materials (industrial spent coffee grounds,20 soybean oil,21 canola oil22) confirmed that this process allows to increase oxidation stability because of co-extraction of natural antioxidants (mainly tocopherols).

In this work, the oxidation stability of grapeseed oil FAEE is studied using grapeseed oil FAME as a reference for comparison and including possible improvements of this property by mixing these biofuels with FAEE and FAME produced via in situ transesterification (hereinafter denoted as in situ FAEE and in situ FAME) or adding with antioxidants extracted from grapeseed or defatted grapeseed flour. The antioxidant concentration was correlated to UV–vis spectroscopy measurements. Biofuel production and antioxidant extraction processes and yields are presented and compared to those published in the literature.

2. Materials, Equipment, and Methods

2.1. Materials

The following materials were used for the production of conventional alkyl esters: refined grapeseed oil, donated by Movialsa S.A.; absolute ethanol and methanol (both from Panreac Applichem); sodium ethoxide (21% w/w in ethanol) and sodium methoxide (30% w/w in methanol) (both from Acros Organics); sodium chloride (supplied by Glass Chemicals); and a 4 Å molecular sieve (pearl-shaped 2–3 mm; Scharlau).

Grapeseed used in the in situ transesterification and in the antioxidant extraction was the same as that used in the previous work.8 Methanol (Panreac Applichem) and hydrochloric acid (AnalaR NORMAPUR) were also used in these processes. Defatted grapeseed flour was donated by Alvinesa S.A.

For the experimental measurement of oxidation stability, acetone (Kelsia), distilled water (Bosque Verde), and isopropanol (Panreac Applichem) were used. In addition, butylhydroxytoluene (BHT; SAFC) was used as an additive to improve the oxidation stability of conventional biofuels.

For the evaluation of the natural antioxidant content by UV–vis spectroscopy, the following materials were used: tetrachloroethylene (Uvasol), purchased from Merck; and the double beam UV–vis instrument, which was a Specord 200 Pins of Analytikjena (Germany) with 1 cm quartz cuvettes, controlled by the software WinASPECT PLUS v4.2.0.0.

2.2. Conventional Transesterification

Conventional transesterification of grapeseed oil was carried out to obtain FAEE in a 5 L stirred tank reactor with 3.5 L of refined grapeseed oil, using a molar ratio of ethanol/oil (6:1) and with 2% w/w of sodium ethoxide as the catalyst. The reaction mixture was stirred at 600 rpm and 72 °C for 3 h. After transesterification, G-phase (composed mainly of glycerol, ethanol, and, in minor quantity, mono-, di-, and triglycerides) was recovered in the lower part of separating funnels and separated from the upper phase (FAEE plus ethanol). Ethanol in the biodiesel phase was removed using a rotary evaporator, under 1000 Pa and 50 °C. After ethanol was distilled, a small volume of G-phase and interphases appeared. Next, a purification process was performed through three consecutive washes, with aqueous solutions of sodium chloride (9 and 4% w/w, respectively) and distilled water, using 100% v/v solution with respect to ethyl ester. After the last washing process, the interphase became very faint so that a practically clean ethyl ester was obtained, although with some turbidity. After the purification process, ethyl ester was dried for 24 h to eliminate moisture using a 4 Å molecular sieve (8% w/w with respect to ethyl ester), which was previously activated at 120 °C during 24 h. Finally, FAEE was vacuum-filtered through 45 μm to eliminate suspended particles present in the biofuel. Ethyl ester obtained was kept in an inert nitrogen atmosphere to reduce its eventual oxidation with time. Grapeseed oil FAEE was produced in six batches following the scheme proposed in Figure 1. The volume of grapeseed oil FAEE obtained in each batch is shown in Table 1, as well as each process yield. In total, 18.7 L of grapeseed oil FAEE was produced with an average yield of 89.0%. This yield (89.0%) is almost equal to the yield (90.3%) obtained in the previous work8 and lower than that obtained (97.0%) by Fernández et al.19

Figure 1.

Production scheme for conventional FAEE and FAME from grapeseed oil.

Table 1. Yield Obtained in the Conventional Production of Grapeseed Oil FAEE.

| batch | FAEE (mL) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3130 | 89.4 |

| 2 | 3030 | 86.6 |

| 3 | 3190 | 91.1 |

| 4 | 3070 | 87.7 |

| 5 | 3200 | 91.4 |

| 6 | 3070 | 87.7 |

| total | 18 690 | 89.0 |

FAME was also produced by conventional transesterification of grapeseed oil, using the same molar ratio of methanol/oil (6:1) as for ethyl ester, but using 0.3 L of refined grapeseed oil and 2% w/w sodium methoxide as a catalyst, at 60 °C, 600 rpm, and 3 h. Parameters for the rest of the stages were the same as those previously used (Figure 1). Grapeseed oil FAME was produced in a single batch. Once the production process was finished, 230 mL of grapeseed oil FAME was obtained. Thus, the process yield was 76.7%, slightly lower than the yield (79.8%) obtained by Tijjani et al. for this biofuel.34

2.3. In Situ Transesterification

In situ transesterification was carried out to produce in situ FAEE and in situ FAME from the grounded grapeseed. In both cases, the same parameters were used. In these processes, 50 g of grounded grapeseed previously dried, 180 mL of alcohol (ethanol and methanol, respectively), and 3.4 mL of catalyst (sodium ethoxide and sodium methoxide, respectively) were mixed at 50 °C and 450 rpm during 10 h. Additionally, the processes described were repeated but the grounded grapeseeds were soaked in ethanol and methanol, respectively, during 24 h before reaction. After each process, the sample was vacuum-filtered at 1000 Pa. Next, alcohol recovery was applied to the four samples using a rotary evaporator (50 °C and 1000 Pa). In situ alkyl ester recovered was a semisolid. As long as it includes antioxidants dissolved from the grapeseed, better oxidation stability is expected with respect to alkyl ester produced conventionally. After alcohol recovery, an aliquot part of the in situ FAME sample with 10 h of reaction and no previous soaking of grapeseed in methanol was subjected to washing with an aqueous solution of sodium chloride 9% w/w, using 100% v/v solution with respect to in situ alkyl ester. This washing process was carried out with the objective of verifying how purification with water affects the oxidation stability of FAME. Following this washing process, FAME was dried during 24 h with a 4 Å molecular sieve as it was done in the conventional process.

In summary, five samples of in situ transesterification process were produced, as shown in Figure 2. The yields of in situ FAEE and FAME that were obtained in each process are also indicated in the figure. The average yield of in situ FAEE was 4.6%, whereas it was 7.0% for in situ FAME, slightly lower than that obtained by Fernández et al.19 for this in situ methyl ester. In general, process yields for in situ biofuels are very poor because the oil content of the grapeseed is very low, around 16% v/w.4,5,35

Figure 2.

Production scheme of in situ FAEE and in situ FAME.

2.4. Antioxidant Extraction Process

The antioxidant extraction process was carried out to add both conventional FAEE and FAME to quantify the improvement in oxidation stability. This process was performed through the following sequence: extraction, filtering, and alcohol recovery. First, antioxidant extraction was carried out with 50 g of grounded grapeseed previously dried and 200 mL of methanol solution (0.1% v/v hydrochloric acid), 25 °C, 400 rpm, during 2 h and under a small stream of nitrogen to avoid oxidation (solid lines in Figure 3). The same antioxidant extraction process was performed but with 50 g of defatted grapeseed flour previously dried (dashed lines in Figure 3). The use of hydrochloric acid is justified since it guarantees that phenolic antioxidants remain as phenols (PhOH) and not as phenoxides (PhO–Na+), while methanol is used because it extracts much more antioxidants than ethanol.27 Second, a vacuum filtering was done to retain the solid grapeseed. Finally, methanol was recovered using a rotary evaporator, and, immediately, this methanol was mixed again with the filtered grapeseed solids, subjected to the extraction process with the same parameters described above but only for 1 h. As a result, a solid mix was obtained, expectedly rich in antioxidants. After the whole process, 10.8 g of the mixture with a wide variety of antioxidants27 was obtained from the grounded grapeseed and 0.40 g of the mixture from defatted grapeseed flour. Thus, a process yield of 21.6% was attained from the grounded grapeseed, much higher than that obtained (7.9%) by Braga et al.,23 and a process yield of 0.8% was attained from defatted grapeseed flour, lower than that obtained (up to 2.6%) by Gubsky et al.36

Figure 3.

Natural antioxidant extraction process from the grounded grapeseed and from defatted grapeseed flour.

2.5. Oxidation Stability

Oxidation stability quantifies the tendency of fuels to react with air at room temperature. The degradation of biodiesel is due to different factors, such as the nature of original fatty oil composition, biodiesel production method, impurities (e.g., trace metals, free fatty acids, fuel additives), storage and handling conditions, and the conditions between fuel tank and fuel delivery system.14 Standard EN 14214 establishes the minimum of oxidation stability in 8 h for biodiesel when a sample (3.0 g) is tested at 110 °C and exposed to a constant airflow (10 L/h), as established in the standard method EN 14112. The time at which a sharp increase in the conductivity of deionized water (60 mL) is produced, due to the presence of volatile organic acids formed by the oxidation of the fuel, is called the induction time (IT). This time is indicative of the tendency of biodiesel to become unstable, with its consequent loss of quality and useful life to be used in engines. To measure the induction time of the grapeseed biofuels studied, the Rancimat instrument Methrom AG model 743 was used.

2.6. UV–Vis Spectroscopy

The FAEE/FAME sample (0.015 g) was dissolved in tetrachloroethylene in a 5 mL volumetric flask, and the sample was measured with the UV–vis instrument scanning from 275 to 400 nm at a 1 nm/s rate.

For the Folin–Ciocalteau test, 300 μL of the FAEE/FAME sample was dissolved in 2 mL of methanol, and 0.5 mL of this solution was mixed with 2.5 mL of the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent in a test tube. A portion of 2 mL of 7.5% w/v of freshly prepared sodium carbonate was added to the test tube, and the mixture was warmed at 50 °C in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. The absorbance was determined by placing the sample in a 1 cm polystyrene cuvette and measuring at 760 nm for 1 s. The same procedure was carried out with 0.5 mL of methanol for obtaining the blank. The total phenolic content of the FAEE/FAME samples was determined using a graphical regression analysis of gallic acid standard solutions (10, 30, 50, 70, 100, and 200 mg/L in ethanol–water) versus absorbance (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). The results were expressed in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per liter of FAEE/FAME.

2.7. Description of the Experiments

Oxidation stability was measured for the following samples (see Figure 4):

Grapeseed oil FAEE and grapeseed oil FAME produced from refined grapeseed oil, without additives and with 1000 mg/kg of BHT.

FAEE/in situ FAEE (1 and 2) and FAME/in situ FAME (1, 2, and 3) mixtures, each of them with 20% w/w of in situ biofuel. This content was below the solubility limit in the conventional biodiesel.

FAEE/in situ FAME 2 mixtures, with 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30% w/w of in situ biofuel. In this case, the range of mixtures was extended to 30% because the solubility of in situ FAME in FAEE was found to be slightly higher.

FAEE and FAME (both conventional) added with 1000 and 2000 mg/kg (each of them), respectively, of the product of antioxidant extraction process carried out with grounded grapeseed.

FAEE and FAME (both conventional) added with several doses approximately between 200 and 2000 mg/kg of the product of antioxidant extraction process carried out with defatted grapeseed flour.

Figure 4.

Experimental scheme for grapeseed oil FAEE and grapeseed oil FAME (mixture and additional dosages shown in this scheme correspond to target values).

In summary, oxidation stability measurements were carried out for 28 biofuel samples with different compositions, with the aim to compare the oxidation stability of conventional grapeseed oil FAEE and grapeseed oil FAME. A second objective was to evaluate how efficient is mixing grapeseed oil FAEE with in situ FAEE and in situ FAME and to compare this efficiency to that obtained when grapeseed oil FAME is mixed with in situ FAME. A third objective was to examine how efficient is external addition of natural antioxidants extracted either from the grounded grapeseed (before oil extraction) or from defatted grapeseed flour (after oil extraction) compared to external addition of a synthetic phenol-type antioxidant (BHT). A repeatability study made on FAEE samples led to a relative standard error (RSE) for induction period measurements of 12%. The observed effects were considered significant when variations were higher than RSE.

3. Results and Discussion

All of the accelerated oxidation curves (conductivity vs time) obtained from the Rancimat tests are shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Information), and the induction times obtained are discussed in the following section.

3.1. Grapeseed Oil FAEE and Grapeseed Oil FAME without Additives and with BHT

Table 2 shows the experimental results obtained from the oxidation stability of grapeseed oil FAEE and grapeseed oil FAME without additives and with the addition of 1000 mg/kg of BHT. Conventional grapeseed oil FAME showed an induction time much higher than FAEE (1.28 vs 0.18 h), although it was still below the lower limit (8 h) set by the standard EN 14214.9 Addition of 1000 mg/kg of BHT improved the oxidation stability of both grapeseed oil FAEE and grapeseed oil FAME, although it was not enough to reach the lower limit, and therefore, increased additional dosages would be necessary. This well-known effect of BHT addition is just used here as a reference for comparison.

Table 2. Oxidation Stability of FAEE and FAME without and with BHT.

| type of biofuel | dosage of BHT (mg/kg) | IT (h) |

|---|---|---|

| FAEE | 0 | 0.18 |

| 1015 | 0.97 | |

| FAME | 0 | 1.28 |

| 1025 | 3.24 |

3.2. FAEE/In Situ FAEE, FAME/In Situ FAME, and FAEE/In Situ FAME Mixtures

Table 3 shows the experimental results of oxidation stability obtained for FAEE/in situ FAEE (1 and 2) 80/20% w/w and for FAME/in situ FAME (1, 2, and 3) 80/20% w/w mixtures, as well as FAEE/in situ FAME mixtures (95/5, 90/10, 85/15, 80/20, and 70/30% w/w). Figure 5 also shows the oxidation stability obtained for mixtures vs mass fraction of in situ alkyl ester. Only in the case of FAEE/in situ FAME 2 mixtures, six different contents were tested, which permitted observing a linear increase in the induction time (R2 = 0.9672). This evidence suggested restricting the number of contents to just two (0 and 20% w/w in all cases) to analyze the rest of the effects, considering the scarcity of samples and the solubility limit (around 30% of in situ alkyl ester). On the one hand, FAEE improved its oxidation stability after being mixed with in situ FAEE 1 and much more after being mixed with in situ FAEE 2 (with grapeseed soaked in ethanol for 24 h prior to the transesterification reaction). However, FAEE showed such a low induction time (0.18 h) that these mixtures also presented low induction times (0.51 and 1.01 h, respectively), very far from the lower limit. Similarly, the oxidation stability of FAME was improved after being mixed with in situ FAME 1 and even more after being mixed with in situ FAME 2 (with grapeseed soaked in methanol for 24 h before reaction). FAME/in situ FAME 1 mixture still remains (6.48 h) below the lower limit, but FAME/in situ FAME 2 mixture surpasses (9.81 h) this limit. However, FAME/in situ FAME 3 mixture slightly improved (2.66 h) the oxidation stability of pure FAME (1.28 h) due to water washing, which removes antioxidants from in situ FAME. On the other hand, the oxidation stability of FAEE was improved as a proportion of in situ FAME 2 increased, with the mixture FAEE/in situ FAME 2 70/30% w/w showing the highest oxidation stability (2.56 h) in this subgroup of samples. Again, FAEE showed such a low induction time (0.18 h) that these FAEE/in situ FAME 2 mixtures (95/5, 90/10, 85/15, 80/20, and 70/30% w/w) also presented low induction times (0.86, 1.04, 1.25, 1.85, and 2.56 h, respectively), far from the lower limit. Considering all of these results, it can be concluded that the use of in situ biodiesel to improve oxidation stability is more effective, with prior soaking of grapeseed in alcohol.

Table 3. Oxidation Stability of FAAE/In Situ FAAE Mixtures.

| mixture | treatment of in situ biofuel | concentration (% w/w) | IT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| conventional FAEE/in situ FAEE | without soaking | 79.9/20.1 | 0.51 |

| with soaking | 80.0/20.0 | 1.01 | |

| conventional FAEE/in situ FAME | with soaking | 94.7/5.3 | 0.86 |

| 89.8/10.2 | 1.04 | ||

| 83.7/16.3 | 1.25 | ||

| 79.6/20.4 | 1.85 | ||

| 70.8/29.2 | 2.56 | ||

| conventional FAME/in situ FAME | without soaking | 80.4/19.6 | 6.48 |

| with soaking | 79.9/20.1 | 9.81 | |

| with washing | 79.7/20.3 | 2.66 |

Figure 5.

Induction time, IT (h), vs mass fraction of in situ biofuel, Yin situ (% w/w).

3.3. Grapeseed Oil FAEE and Grapeseed Oil FAME with Addition of Antioxidants Extracted from Grapeseed

Table 4 and Figure 6 show the experimental results of oxidation stability obtained from conventional FAEE and FAME, with addition of 1000 and 2000 mg/kg of antioxidants, respectively, extracted from the grounded grapeseed. The oxidation stability of FAEE was improved after addition of 1000 mg/kg of antioxidants, practically the same as with 2000 mg/kg of antioxidants. This could be explained because 1000 mg/kg is close to the solubility limit of these antioxidants in FAEE (at ambient temperature), and therefore, additional antioxidant content becomes ineffective. Once again, induction times lower than the minimum limit (8 h) set by EN 142149 were obtained. On the other hand, the oxidation stability of FAME was hardly improved after addition of 1000 mg/kg of extracted antioxidants, and it was even reduced with 2000 mg/kg of antioxidants (solubility limit at ambient temperature was reached). Once again, addition of 1000 mg/kg reached a saturation point and no more extracted antioxidants could be dissolved in this biofuel.

Table 4. Oxidation Stability of FAEE and FAME with Addition of Antioxidants.

| type of biofuel | addition | dosage (mg/kg) | IT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAEE | antioxidants extracted from grounded grapeseed | 1013 | 0.78 |

| 1992 | 0.75 | ||

| antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour | 190 | 0.18 | |

| 330 | 0.45 | ||

| 590 | 0.49 | ||

| 750 | 0.51 | ||

| 1040 | 0.49 | ||

| 1490 | 0.53 | ||

| 1980 | 0.55 | ||

| FAME | antioxidants extracted from grounded grapeseed | 1021 | 1.34 |

| 1977 | 1.01 | ||

| antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour | 460 | 1.29 | |

| 990 | 1.31 | ||

| 1890 | 1.27 |

Figure 6.

Induction time (IT) (h) vs additional dosage (mg/kg).

3.4. Grapeseed Oil FAEE and Grapeseed Oil FAME with Addition of Antioxidants Extracted from Defatted Grapeseed Flour

Oxidation stability measurements for grapeseed oil FAEE and FAME added with antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour (results also shown in Table 4) are plotted against additional dosage in Figure 6. The natural antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour have poor solubility in FAEE (Figure S1 at the Supporting Information), and as consequence, the oxidation stability of these esters hardly improved as dosing increased, as shown in the solid circles of Figure 7. However, when the samples were stirred manually before the test, the oxidation stability improved more than without stirring and showed good correlation as the dosage was increased (solid squares in Figure 7). Moreover, when the samples were stirred manually just before the beginning of the test at 110 °C, the oxidation stability improved much more (solid triangles in Figure 7) although correlating worse than when samples were stirred before the test. This demonstrates that the addition of natural antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour could be a promising method to improve the oxidation stability of FAEE, as far as they can be solubilized. In the case of FAME added with antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour, the oxidation stability did not improve as the dosage was increased (empty triangles in Figure 7), in spite of stirring the samples just before the beginning of the test.

Figure 7.

Induction time, IT (h), vs additional dosage of natural antioxidants extracted from defatted grapeseed flour, Yd.g.f. (mg/kg), where d.g.f. denotes defatted grapeseed oil.

3.5. Evaluation of Natural Antioxidants by UV–Vis Spectroscopy

All of the samples analyzed show a maximum in absorbance at 285 nm, which corresponds to the absorbance of phenolic compounds such as catechin (Figure 8), which are natural antioxidants present in grapeseed.37,38

Figure 8.

Structure of (−)-catechin.

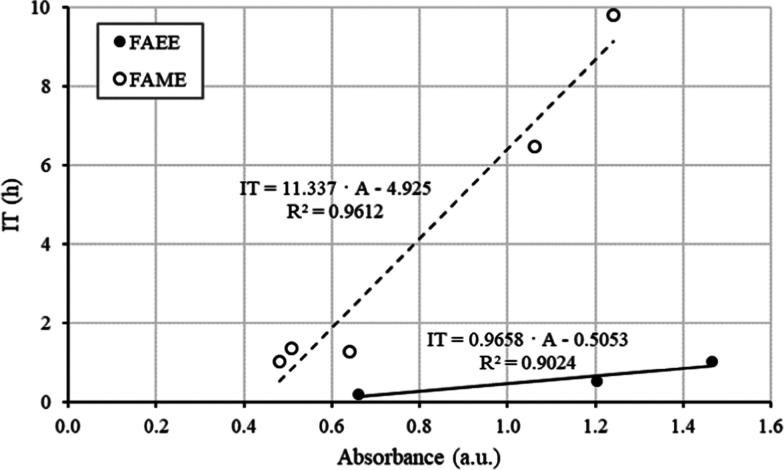

The oxidation stability of the mixtures of conventional and in situ alkyl esters included in Tables 2–4 was plotted against the absorbance at a wavelength of 285 nm, and a clear linear relationship was observed for FAEE and FAME (Figure 9). The oxidation stability for FAME is much higher than that for FAEE because methanol has a much greater extraction capacity of natural antioxidants than ethanol.27,39−41 This is likely the reason why in situ transesterification with methanol improved the IT of FAME above the EN 14214 requirement, but for FAEE, this improvement does not reach the minimum value of 8 h.

Figure 9.

Induction time (h) vs absorbance (au) at 285 nm for FAEE and FAME.

To confirm that the IT improvement observed was due to the presence of natural antioxidants in the samples, the Folin–Ciocalteu42 test was carried out for the FAEE and FAME samples. The IT versus the resulting antioxidant content of the samples, expressed in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per liter of the sample, was plotted (Figure 10). Although the coefficients of correlation are not excellent, they are high enough (around 0.94) to confirm that the higher extraction capacity of methanol over ethanol for the natural antioxidants detected with this method produces a much higher increase in the induction time for FAME than for FAEE.

Figure 10.

Induction time (h) vs gallic acid equivalent (mg/L) for FAEE and FAME.

The results presented in this section demonstrate that the natural antioxidants present in the grapeseed could play a key role in the improvement of the oxidation stability of its derived FAEE, as far as they can be efficiently extracted and solubilized.

4. Conclusions

The results of the oxidation stability obtained for the grapeseed biofuels analyzed allow to reach the following conclusions:

Grapeseed oil FAEE showed lower oxidation stability than grapeseed oil FAME, which can be explained because ethanol has a lower antioxidant extraction capacity than methanol. Both grapeseed oil alkyl esters showed very poor oxidation stability, which may be due to the industrial refining that may have removed natural antioxidants in the grapeseed oil.

FAEE and FAME produced via in situ transesterification showed better oxidation stability than the same alkyl esters obtained by conventional transesterification, as inferred from the improvement in this property for mixtures with respect to conventional FAEE and FAME, respectively.

In situ biofuels showed better oxidation stability with prior soaking in alcohol than without prior soaking.

Washing of in situ FAME with water led to only slight improvement in oxidation stability, as a consequence of the removal of a large amount of antioxidants present in the in situ FAME.

Grapeseed oil FAEE showed higher oxidation stability when it was mixed with in situ FAME than with in situ FAEE.

Addition of grapeseed oil FAEE with natural antioxidants extracted either from grounded grapeseed or from defatted grapeseed flour improved its oxidation stability. However, such improvement was not obtained when the grapeseed oil FAME was added with the aforementioned antioxidants.

The improvements in the oxidation stability of grapeseed oil alkyl esters obtained with the addition of either in situ alkyl esters or natural antioxidants are limited by their solubility in conventional alkyl esters and can be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds. This presence has been demonstrated by the correlation between the induction time and both the absorbance at 285 nm and the phenolic content in the mixtures.

Grapeseed oil FAEE is a viable and fully renewable fuel, which would contribute to reaching the target established in the Directive (EU) 2018/2001 related to the presence of advanced biofuels in the final energy consumed by 2030 in the transport sector. The only disadvantage of grapeseed oil FAEE is its lower oxidation stability with respect to grapeseed oil FAME, but it can be solved either by mixing FAEE with in situ FAEE, preferably, or with in situ FAME, or by adding FAEE with natural antioxidants presented in grapeseed. This mixing or natural addition is probably not enough to reach the minimum limit established in the biodiesel standard EN 14214, but at least it would save on chemical antioxidants, which is one of the usual costs in the biodiesel industry.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla—La Mancha (Project FUELCAM, SBPLY/17/180501/000299) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also wish to thank the graduate students Jean Pierre Jurado Roca and Silvia Sánchez de la Llama (UPM) for their technical contribution to this work and the companies Movialsa S.A. (Campo de Criptana, Ciudad Real, Spain) and Alvinesa S.A. (Daimiel, Ciudad Real, Spain) for the generous supply of raw materials.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01496.

Photograph of samples added with natural antioxidants, absorbance–concentration calibration correlations, and induction time diagrams from Rancimat tests (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bret A.The Energy-Climate Continuum, 1st ed.; Springer: Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001. Directive (EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Official Journal of the European Union; 2018.

- International Organization of Vine and Wine. Statistical Report on World Vitiviniculture; OIV, version 1, 2019.

- De Haro J. C.; Rodríguez J. F.; Carmona M.; Pérez A.. Revalorization of Grape Seed Oil for Innovative Non-Food Applications. In Grapes and Wines – Advances in Production, Processing, Analysis and Valorization; InTechOpen: London, 2018; Chapter 16. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer K.; Hosseinian F.; Rod M. The market potential of grape waste alternatives. J. Food Res. 2014, 3, 91–106. 10.5539/jfr.v3n2p91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera I.; Lago C.; Lechón Y.; Sáez R. M.. Análisis del ciclo de vida de combustibles alternativos para el transporte: bioetanol y biodiésel. CIEMAT, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación: Madrid, 2012.

- Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia. Accessed 18/12/2019. Available at https://www.cnmc.es/.

- Bolonio D.; García-Martínez M. J.; Ortega M. F.; Lapuerta M.; Rodríguez-Fernández J.; Canoira L. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) obtained from grapeseed oil: A fully renewable biofuel. Renewable Energy 2019, 132, 278–283. 10.1016/j.renene.2018.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. EN 14214:2013 V2+A2:2019. Liquid Petroleum Products - Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Use in Diesel Engines and Heating Applications - Requirements and Test Methods, 2019.

- Antolovich M.; Prenzler P. D.; Patsalides E.; McDonald S.; Robards K. Methods for testing antioxidant activity. Analyst 2002, 127, 183–198. 10.1039/b009171p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge N.; Malacrida C. R.; Angelo P. M.; Andreo D. Proximal composition and antioxidant activity of the extract of passion fruit seeds (Passiflora edulis) in soybean oil. Agric. Res. Trop. 2009, 39, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- Adhvaryu A.; Erhan S. Z.; Liu Z. S.; Perez J. M. Oxidation kinetic studies of oils derived from unmodified and genetically modified vegetables using pressurized differential scanning calorimetry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 364, 87–97. 10.1016/S0040-6031(00)00626-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaid A.; Martínez M.; Aracil J. Production of biodiesel from bioethanol and Brassica carinata oil: oxidation stability study. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2234–2239. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen J.; Saeed K. An overview of biodiesel oxidation stability. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5924–5950. 10.1016/j.rser.2012.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monyem A.; Van Gerpen J. H. The effect of biodiesel oxidation on engine performance and emissions. Biomass Bioenergy 2001, 20, 317–325. 10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00095-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D. Y. C.; Koo B. C. P.; Guo Y. Degradation of biodiesel under different storage conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 97, 250–256. 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayner D. D. M.; Burton G. W.; Ingold K. U.; Locke S. Quantitative measurement of the total, peroxyl radical-trapping antioxidant capability of human blood plasma by controlled peroxidation. The important contribution made by plasma proteins. FEBS 1985, 187, 33–37. 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardauil J. J. R.; de Molfetta F. A.; Braga M.; de Souza L. K. C.; Filho G. N. R.; Zamian J. R.; da Costa C. E. F. Characterization, thermal properties and phase transitions of amazonian vegetable oils. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 1221–1229. 10.1007/s10973-016-5605-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- María Fernández C.; Ramos M. J.; Pérez A.; Rodríguez J. F. Production of biodiesel from winery waste: extraction, refining and transesterification of grape seed oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7019–7024. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuntiwiwattanapun N.; Monono E.; Wiesenborn D.; Tongcumpou C. In-situ transesterification process for biodiesel production using spent coffee grounds from the instant coffee industry. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 102, 23–31. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. J.; Scott K. M. Moisture removal substantially improves the efficiency of in situ biodiesel production from soybeans. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 197–204. 10.1007/s11746-006-1024-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haagenson D. M.; Brudvik R. L.; Lin H.; Wiesenborn D. P. Implementing an in situ alkaline transesterification method for canola biodiesel quality screening. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 1351–1358. 10.1007/s11746-010-1607-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braga G. C.; Melo P. S.; Bergamaschi K. B.; Tiveron A. P.; Massarioli A. P.; De Alencar S. M. Extraction yield, antioxidant activity and phenolics from grape, mango and peanut agro-industrial by-products. Ciencia Rural 2016, 46, 1498–1504. 10.1590/0103-8478cr20150531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M. S. Natural antioxidants: Sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 221–247. 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00156.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nijveldt R. J.; Van Nood E.; Van Hoorn D. E. C.; Boelens P. G.; Van Norren K.; Van Leeuwen P. A. M. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 418–425. 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo-Branco V. N.; Santana I.; Di-Sarli V. O.; Freitas S. P.; Torres A. G. Antioxidant capacity is a surrogate measure of the quality and stability of vegetable oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 224–235. 10.1002/ejlt.201400299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T.; Schieber A.; Kammerer D. R.; Carle R. Residues of grape (Vitis viniferaL.) seed oil production as a valuable source of phenolic antioxidants. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 551–559. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes D. M.; Sousa R. M. F.; de Oliveira A.; Morais S. A. L.; Richter E. M.; Muñoz R. A. A. Moringa oleifera: A potential source for production of biodiesel and antioxidant additives. Fuel 2015, 146, 75–80. 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.12.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M. J.; Fernández C. M.; Casas A.; Rodríguez L.; Pérez A. Influence of fatty acid composition of raw materials on biodiesel properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 261–268. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuerta M.; Rodríguez-Fernández J.; Font de Mora E. Correlation for the estimation of the cetane number of biodiesel fuels and implications on the iodine number. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4337–4344. 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuerta M.; Sánchez-Valdepeñas J.; Bolonio D.; Sukjit E. Effect of fatty acid composition of methyl and ethyl esters on the lubricity at different humidities. Fuel 2016, 184, 202–210. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garavaglia J.; Markoski M. M.; Oliveira A.; Marcadenti A. Grape seed oil compounds: biological and chemical actions for health. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2016, 9, 59–64. 10.4137/NMI.S32910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malićanin M.; Rac V.; Antic V. V.; Antic M.; Palade M.; Kefalas P.; Rakic V. Content of antioxidants, antioxidant capacity and oxidative stability of grape seed oil obtained by ultra sound assisted extraction. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 989–999. 10.1007/s11746-014-2441-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tijjani N.; Magaji U. I.; Zuru A. A.; Usman K. M.; Habib Y. B. Production of biodiesel from wild grape seed. NSE Tech. Trans. 2011, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila I.; Robles E.; Egüés I.; Labidi J.; Gullón P.. The Biorefinery Concept for the Industrial Valorization of Grape Processing By-products. In Handbook of Grape Processing By-products: Sustainable Solutions; Academic Press – Elsevier: London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gubsky S.; Labazov M.; Samokhvalova O.; Grevtseva N.; Gorodyska O. Optimization of extraction parameters of phenolic antioxidants from defatted grape seeds flour by response surface methodology. Ukr. Food J. 2018, 7, 627–639. 10.24263/2304-974X-2018-7-4-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. H.; Kim S. K.; Shin M. G.; Kim K. H. Comparative study of physical methods for lipid oxidation measurement in oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1985, 62, 1487–1489. 10.1007/BF02541899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M.; Nie Y.; Zheng X. Q.; Lu J. L.; Liang Y. R.; Ye J. H. Ultraviolet B (UVB) photosensitivities of tea catechins and the relevant chemical conversions. Molecules 2016, 21, 1345. 10.3390/molecules21101345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaludin N. H. I.; Sa’adi R. A.; Abdullah N. A. H.; Arbain D. Isolation of antioxidant compound by TLC-based approach from Limau kasturi (Citrus macrocarpa) peels extract. Am. - Eurasian J. Sustain. Agric. 2015, 9, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santos M. C. P.; Gonçalves E. C. B. A. Effect of different extracting solvents on antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of a fruit and vegetable residue flour. Sci. Agropecu. 2016, 7, 07–14. 10.17268/sci.agropecu.2016.01.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana B.; Anwar F.; Ashraf M. Effect of extraction solvent/technique on the antioxidant activity of selected medicinal plant extracts. Molecules 2009, 14, 2167–2180. 10.3390/molecules14062167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton V. L.; Orthofer R.; Lamuela-Raventós R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.