Mycobacterium abscessus, a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterium, is increasingly prevalent in chronic lung disease, including cystic fibrosis, and infections are characterized by neutrophil-dominated environments. However, mechanisms of immune control are poorly understood. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic with immunomodulatory effects, is used to treat M. abscessus infections. Recently, inhibition of macrophage bactericidal autophagy was described for azithromycin, which could be detrimental to the host.

KEYWORDS: azithromycin, cell trafficking, chloroquine, cystic fibrosis, innate immunity, phagocytosis, reactive oxygen species, wortmannin

ABSTRACT

Mycobacterium abscessus, a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterium, is increasingly prevalent in chronic lung disease, including cystic fibrosis, and infections are characterized by neutrophil-dominated environments. However, mechanisms of immune control are poorly understood. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic with immunomodulatory effects, is used to treat M. abscessus infections. Recently, inhibition of macrophage bactericidal autophagy was described for azithromycin, which could be detrimental to the host. Therefore, we explored the role of autophagy in mycobactericidal neutrophils. Azithromycin did not affect M. abscessus-induced neutrophil reactive oxygen species formation, phagocytosis, or cytokine secretion, and neutrophils treated with azithromycin killed M. abscessus equally as well as untreated neutrophils from either healthy or cystic fibrosis subjects. One clinical isolate was killed more effectively in azithromycin-treated neutrophils, suggesting that pathogen-specific factors may interact with an azithromycin-sensitive pathway. Chloroquine and rapamycin, an inhibitor and an activator of autophagy, respectively, also failed to affect mycobactericidal activity, suggesting that autophagy was not involved. However, wortmannin, an inhibitor of intracellular trafficking, inhibited mycobactericidal activity, but as a result of inhibiting phagocytosis. The effects of these autophagy-modifying agents and azithromycin in neutrophils from healthy subjects were similar between the smooth and rough morphotypes of M. abscessus. However, in cystic fibrosis neutrophils, wortmannin inhibited killing of a rough clinical isolate and not a smooth isolate, suggesting that unique host-pathogen interactions exist in cystic fibrosis. These studies increase our understanding of M. abscessus virulence and of neutrophil mycobactericidal mechanisms. Insight into the immune control of M. abscessus may provide novel targets of therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium abscessus is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) that is emerging as an important pathogen in chronic lung disease, including cystic fibrosis (CF) (1–8). In CF, M. abscessus infection is associated with an accelerated decline in lung function and incomplete therapeutic options due to intrinsic antibiotic resistance (6, 9, 10). Two distinct colony morphologies, or morphotypes, are observed during culture on solid media. The smooth morphotype, characteristic of environmental isolates, is associated with biofilm formation, poor recognition by immune cells, sliding motility, and expression of a specialized cell envelope molecule, glycopeptidolipid. The rough morphotype is an adaptive change observed during in vivo growth, and is characterized by a loss of glycopeptidolipid, extensive clumping, enhanced recognition by immune cells, and increased virulence (11).

Progression from infection to disease is poorly understood, but involves complex processes, including conversion to the rough morphotype, virulence factor expression, and host genetic background (11, 12). Similarities with M. tuberculosis have directed NTM research toward macrophages as the primary cell studied (13–17). Macrophage phagocytosis of both smooth and rough M. abscessus morphotypes occurs, but the smooth morphotype is readily cleared, while the rough morphotype eludes intracellular killing (18–23). Recent studies have described a role for macrophage autophagy in the clearance of NTM and M. tuberculosis (24–27).

Infections with M. abscessus are highlighted by neutrophil accumulation and inflammatory conditions (28), suggesting that neutrophils play an important role in M. abscessus pathogenesis. Neutrophils use intracellular and extracellular mechanisms to kill M. abscessus (29), but these bactericidal pathways are inefficient compared to the ability to control other bacteria, and may exploit this limited control to its advantage (30). In neutrophils, intracellular mechanisms of M. abscessus killing are poorly understood.

Azithromycin (AZM) is a macrolide antibiotic, and it is one of the few therapeutic options for NTM infections (8). In addition to its antibiotic activity, AZM displays immunomodulatory effects to alter host responses to pathogens, including increased bactericidal activity but inhibition of inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS), neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and eicosanoid synthesis (31–39). A novel immunomodulatory activity of AZM was described by Renna et al. during NTM infection, resulting in inhibition of macrophage autophagy and increased survival of M. abscessus (40), specifically by inhibiting lysosome acidification and reducing lysosome-phagosome fusion. The authors hypothesized that AZM treatment was associated with an increase in NTM infection in the CF population. While detailed clinical studies have not found an association of AZM therapy and NTM infections (41), the possibility that AZM alters autophagy-dependent killing suggests it may be an important molecular tool to dissect intracellular bactericidal processes (40, 42, 43).

The finding that AZM inhibits macrophage autophagy during NTM infection led us to explore the effects of AZM on neutrophil mycobactericidal activity. Surprisingly, neutrophil bactericidal activity was found to be largely independent of autophagy. However, wortmannin, an inhibitor of autophagy and intracellular trafficking, promoted M. abscessus survival, but did so through inhibition of M. abscessus uptake. These studies further define mycobactericidal pathways in neutrophils, and provide a framework for further studies to understand host and pathogen factors important in NTM clearance.

RESULTS

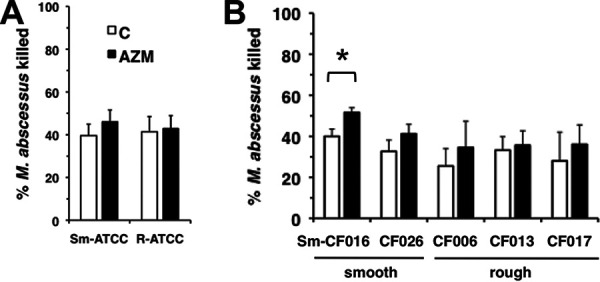

AZM does not inhibit neutrophil killing of M. abscessus.

M. abscessus survival was determined in the presence and absence of AZM to test if AZM affected neutrophil mycobactericidal activity. The killing of the type strains of either morphotype (Sm-ATCC and R-ATCC) by neutrophils from healthy subjects was not affected by AZM (Fig. 1A). Similarly, killing of CF sputum isolates of M. abscessus by neutrophils from healthy subjects was mostly unaffected by AZM (Fig. 1B). The killing of the smooth morphotype of CF016 (Sm-CF016) was enhanced rather than inhibited in the presence of AZM. These data suggest that AZM does not inhibit neutrophil mycobactericidal activity against either morphotype, but it may instead promote neutrophil mycobactericidal activity in a strain-specific manner.

FIG 1.

No inhibition of M. abscessus killing by AZM. (A) Human peripheral neutrophils were incubated with AZM (closed bars; 25 μg/ml) for 20 min and infected with M. abscessus smooth (Sm-ATCC) and rough (R-ATCC) morphotypes for 1 h. Surviving bacteria were compared to the initial inoculum to determine % killing; n = 10 independent experiments. (B) Infection with CF M. abscessus clinical isolates. Morphotypes are indicated below; n = 4 to 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

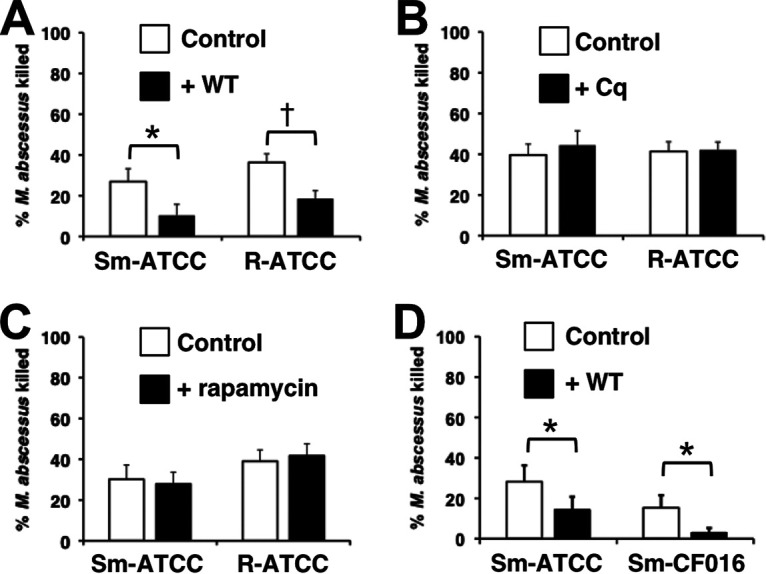

M. abscessus killing is autophagy-independent.

The lack of effect of AZM suggests that neutrophils do not use an AZM-sensitive autophagy pathway. However, neutrophils may use an AZM-insensitive autophagy pathway for intracellular killing. These findings led us to explore neutrophil autophagy pathways in greater detail. The mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTORC1) regulates the unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex that controls the class III phosphatidylinositol (PI3K) vacuolar protein sorting 34 (VPS34), the activation of which promotes autophagosome formation. Wortmannin inhibits VPS34, disrupting this process. Wortmannin inhibited neutrophil killing of M. abscessus (Fig. 2A). However, chloroquine, which similarly inhibits autophagy, but by disrupting phagosome-lysosome fusion, had no effect (Fig. 2B). As these agents inhibit autophagy by distinct mechanisms, but have different effects on neutrophil bactericidal activities, we used rapamycin to clarify if autophagy is a mechanism of M. abscessus killing in neutrophils (44, 45). Rapamycin promotes the activation of mTORC1 and VPS34 to stimulate autophagy. Pretreatment of cells with rapamycin had no effect on neutrophil killing of M. abscessus (Fig. 2C), suggesting that autophagy is not involved. To confirm that wortmannin is effective in inhibiting neutrophil killing, a CF clinical isolate was used. Killing of Sm-CF016 was also inhibited by wortmannin (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Wortmannin inhibits neutrophil killing of M. abscessus. Neutrophils were incubated with wortmannin (WT; 10 μM) (A), chloroquine (Cq; 5 μg/ml) (B), and rapamycin (500 nM) (C) for 20 min and infected with smooth (Sm-ATCC) and rough (R-ATCC) isolates of the type strain; n = 7 to 10 independent experiments. (D) Neutrophil killing of Sm-ATCC is compared to a smooth clinical isolate (Sm-CF016) in cells treated with wortmannin (WT); n = 6 to 7. *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.001.

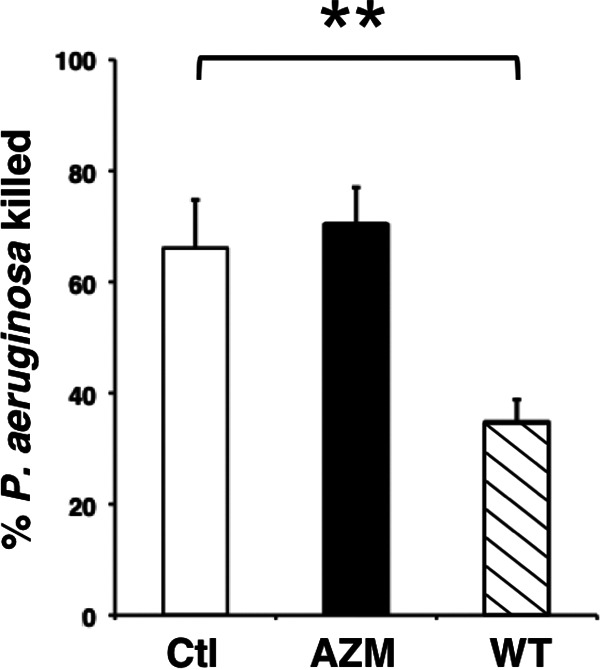

No effect of AZM on Pseudomonas aeruginosa killing.

Bacterial species may be processed through different intracellular pathways. To test the specificity of AZM and wortmannin on neutrophil bactericidal activity, P. aeruginosa killing was assessed. AZM treatment did not affect P. aeruginosa killing (Fig. 3). It is important to note that extracellular antibiotic activity of AZM is minimized in this system due to efficient uptake of free AZM by neutrophils (46). In contrast to AZM, wortmannin-treated neutrophils demonstrated reduced killing of P. aeruginosa, while other regulators of autophagy and intracellular trafficking, including rapamycin and chloroquine, did not affect P. aeruginosa killing (not shown).

FIG 3.

Wortmannin inhibits neutrophil killing of P. aeruginosa. Neutrophils were incubated with AZM (closed bar; 25 μg/ml) or wortmannin (WT) (hatched bar; 10 μM) for 20 min and infected with P. aeruginosa PAO1 for 1 h; n = 6 independent experiments. Ctl, control nontreated cells; **, P < 0.01.

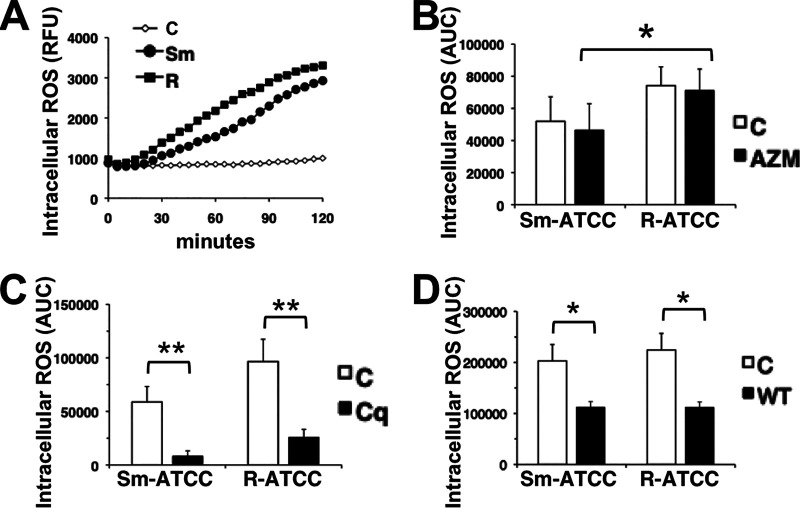

AZM does not affect neutrophil ROS generation and phagocytosis.

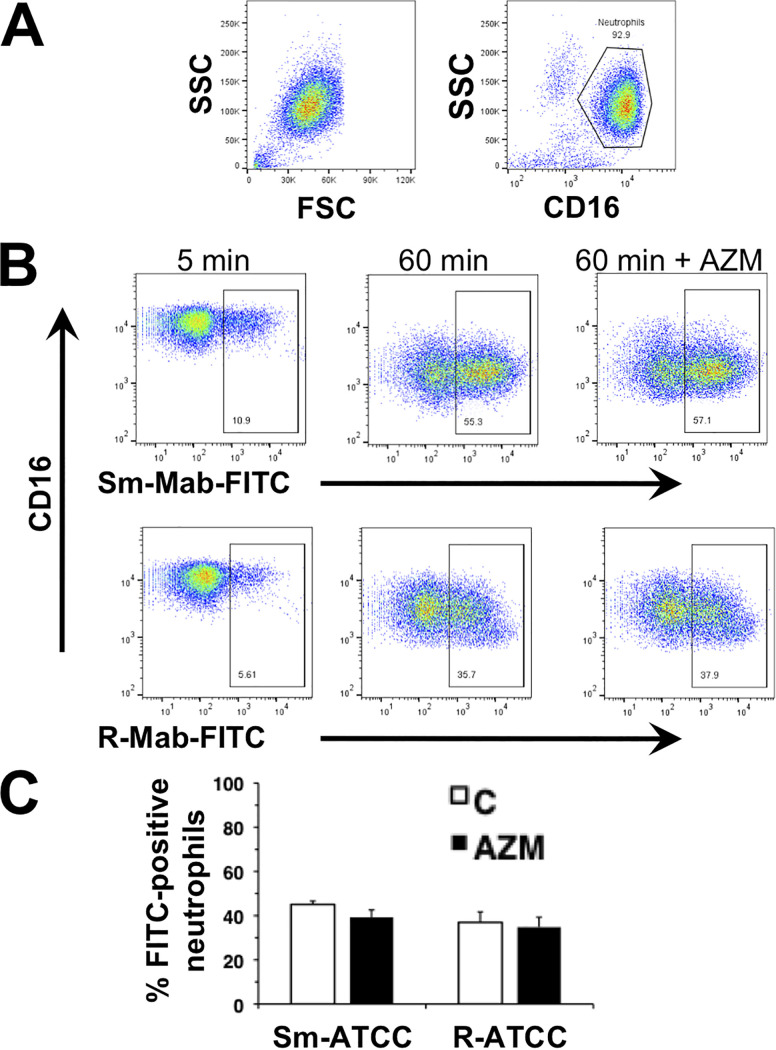

Although M. abscessus is not susceptible to neutrophil ROS (29), AZM may modify ROS generation and indirectly affect immune responses or tissue injury. As shown previously, Sm-ATCC and R-ATCC induced neutrophil intracellular ROS (29), but AZM had no effect on M. abscessus-induced ROS (Fig. 4). The requirement for intracellular targeting was confirmed using cytochalasin D, which inhibited M. abscessus-induced intracellular ROS (not shown) (29). In addition, chloroquine and wortmannin also inhibited M. abscessus-induced intracellular ROS (Fig. 4C and D), supporting an intracellular trafficking effect for these agents. No change in the level of phagocytosis between morphotypes was observed (Fig. 5). Furthermore, AZM did not affect the extent of neutrophil phagocytosis, or loss of cell surface CD16 expression, a marker for neutrophil activation, of either morphotype.

FIG 4.

Azithromycin does not affect intracellular ROS production. (A) Time course of intracellular ROS production; RFU, relative fluorescence units. Neutrophils were incubated with the ROS detection reagent CM-H2DCFA and infected with Sm-ATCC (closed circle) or R-ATCC (closed square). (B) Area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of ROS production over 120 min in the absence or presence of AZM (closed bars; 25 μg/ml). (C) AUC of ROS production in the absence or presence of chloroquine (Cq, 5 μg/ml; closed bars). (D) AUC of ROS production in the absence or presence of wortmannin (WT, 10 μg/ml; closed bars); n = 3 to 8. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

FIG 5.

Azithromycin does not affect phagocytosis. Neutrophils were incubated with FITC-labeled Sm-ATCC and R-ATCC (FITC-Mab) for the indicated times. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) of nonstimulated neutrophils, and gating of Alexa Fluor-450-conjugated anti-CD16. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of FITC-Mab association with CD16+ neutrophils, indicated by the boxed region, at 5 and 60 min in the absence and presence of AZM. Examples of smooth (Sm-Mab; upper panels) and rough (R-Mab; lower panels) M. abscessus uptake are shown. (C) Summary of the effect of AZM (closed bars) on neutrophil uptake of M. abscessus; n = 5.

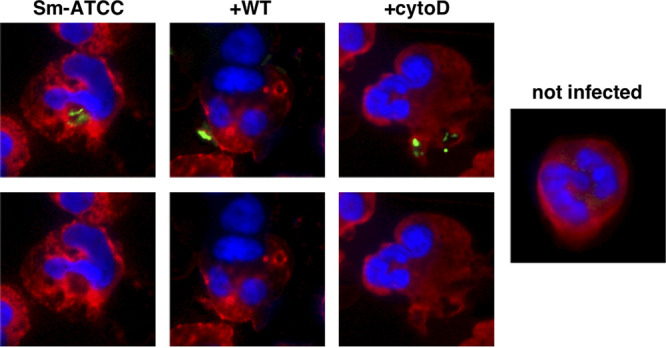

In control infected neutrophils, intracellular localization of Sm-FITC occurred in zones that excluded elastase (Fig. 6) (29). AZM-treated neutrophils similarly resulted in intracellular localization of Sm-FITC in zones that excluded elastase (not shown). Interestingly, immunofluorescence analysis in wortmannin-treated neutrophils demonstrated a peripheral localization of M. abscessus (Fig. 6), similar to that seen for cytochalasin D, indicating reduced M. abscessus uptake. Therefore, any intracellular effects of wortmannin appear secondary to inhibition of uptake.

FIG 6.

Wortmannin inhibits M. abscessus phagocytosis. Neutrophils were incubated with FITC-Mab (green; Sm-ATCC) for 1 h in the presence of wortmannin (WT; 10 μM) or cytochalasin D (cytoD; 5 μg/ml). Following cytocentrifugation, neutrophils were stained for neutrophil elastase (red). Images are presented with (upper) and without (lower) FITC-Mab staining to clarify localization. Pictures are representative of 5 independent experiments.

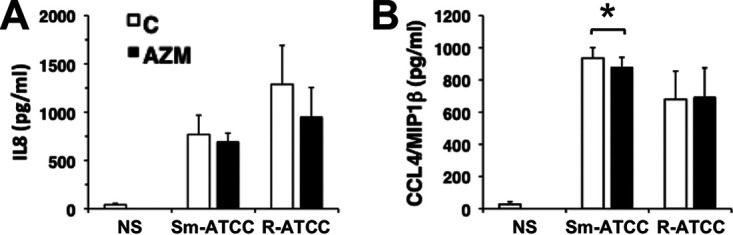

Effect of AZM on cytokine production.

To assess the ability of AZM to modulate a secondary immune response, the levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and CCL4/MIP1β were measured after exposure to M. abscessus. AZM had a modest inhibitory effect on CCL4 production by smooth M. abscessus-treated neutrophils, but had no effect on IL-8, or after exposure to rough M. abscessus (Fig. 7). These data indicate that AZM does not have a profound secondary immune effect on M. abscessus-exposed neutrophils.

FIG 7.

Azithromycin does not affect cytokine secretion. Neutrophils were incubated with AZM (closed bars) and infected with Sm-ATCC or R-ATCC for 2 h, and secretion of IL-8 (A) and CCL4/MIP1β (B) was determined by ELISA; n = 3. *, P < 0.05.

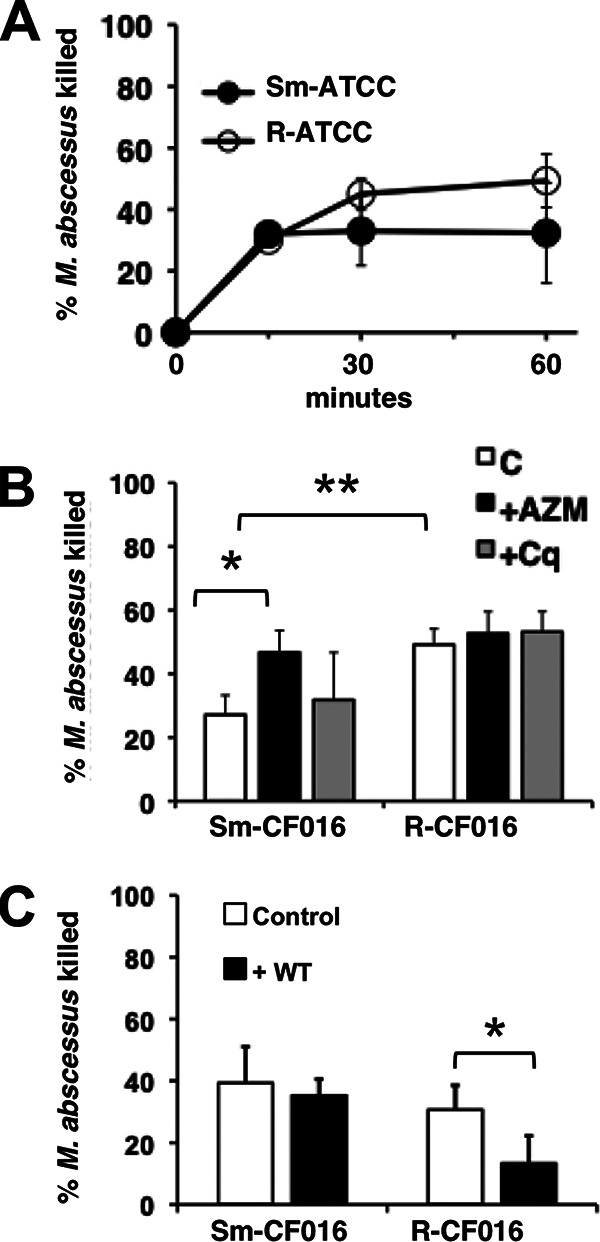

Neutrophils from patients with CF kill M. abscessus.

Immunocompromised patients are at risk for NTM disease (6, 7). The bactericidal activity of CF neutrophils was determined using isogenic smooth (Sm-CF016) and rough (R-CF016) morphotypes isolated from CF sputum. Both clinical morphotypes were killed with similar kinetics (Fig. 8A). As observed in neutrophils from healthy subjects, AZM increased killing of Sm-CF016 by CF neutrophils, while chloroquine had no effect on killing (Fig. 8B). R-CF016 killing was unaffected by either agent (Fig. 8B). For these agents, this particular isogenic pair of isolates had similar responses as the ATCC morphotypes. In contrast to neutrophils from healthy subjects exposed to Sm-ATCC, wortmannin had no effect on the ability of CF neutrophils to kill Sm-CF016 (Fig. 8C), while wortmannin did inhibit killing by CF neutrophils of R-CF016.

FIG 8.

CF neutrophil killing of M. abscessus. (A) CF neutrophils were incubated with Sm-ATCC or R-ATCC for the indicated times. (B) CF neutrophils were incubated with AZM (closed bars; 25 μg/ml) or chloroquine (Cq) (gray bars; 5 μg/ml) before infection with clinical smooth and rough morphotypes of CF016 for 1 h; n = 3. (C) CF neutrophils were incubated with wortmannin (WT) (closed bars; 10 μM) before infection; n = 5 to 7. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The use of AZM in the CF population has increased in recent years (40). AZM has proven to have profound effects on the health status in chronic lung diseases, including decreases in the frequency of pulmonary exacerbations (47–49). Recent studies indicate that AZM inhibits autophagy (40, 42, 43) and mediates increased NTM survival in CF (40). However, the effect of AZM on neutrophils in response to mycobacteria is not well studied. Previous reports indicate that AZM modulates pathogen-exposed neutrophil inflammatory mediator production, ROS, phagocytosis, and killing (35–39). However, classic neutrophil innate immune processes in M. abscessus in the absence of opsonization, such as phagocytosis, ROS generation, and cytokine secretion, were unaffected by acute AZM treatment.

In contrast to the inhibitory effects of AZM reported in macrophages (40), mycobactericidal activity of neutrophils from healthy subjects and subjects with CF was not inhibited by AZM. As dysregulated neutrophilic inflammation is a hallmark of CF lung disease, these data predict that AZM treatment would not be detrimental to the host response to M. abscessus, although CF-specific effects could exist. Furthermore, AZM enhanced, rather than inhibited, killing of a CF isolate of M. abscessus by neutrophils isolated from healthy donors and CF subjects. The finding that AZM enhanced the killing of Sm-CF016, but not other CF isolates, suggests instead that a complex interaction between host and pathogen mediates M. abscessus clearance. Importantly, both Sm-ATCC and Sm-CF016 are similarly susceptible to AZM in in vitro kill assays and by drug susceptibility testing (not shown). While CF016 was isolated from a subject diagnosed with NTM disease, other isolates were isolated from subjects with indolent infections. It may be informative to screen a large number of clinical isolates to establish the extent of this apparent neutrophil-dependent AZM sensitivity, and to determine M. abscessus genetic elements associated with AZM-sensitive and -insensitive strains.

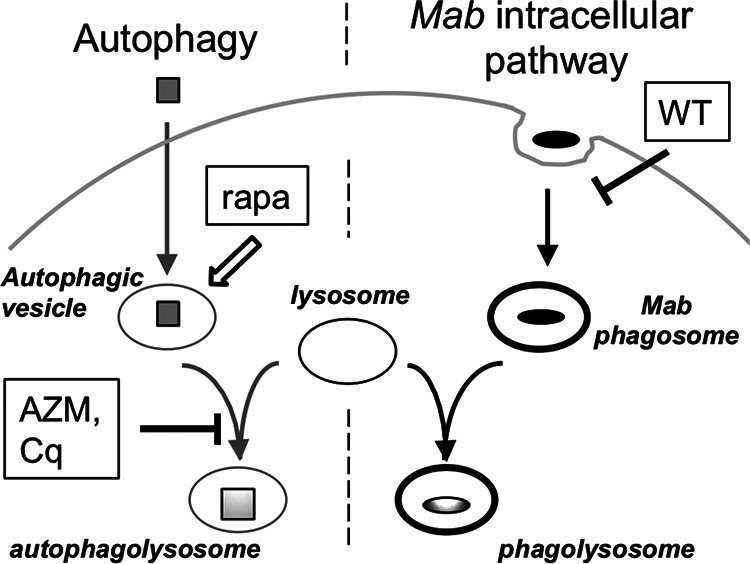

Although AZM had little effect on bactericidal activity, AZM-insensitive autophagy may still participate in neutrophil M. abscessus killing. However, the finding that chloroquine and rapamycin do not modify neutrophil killing suggests that classical autophagy is independent of M. abscessus intracellular processing (Fig. 9). Bactericidal activity in neutrophils that is independent of autophagy is in contrast to autophagy activation in macrophages to many pathogens, including M. abscessus (24, 25, 50–53). Autophagy is bactericidal in macrophages, and escape from autophagy is a strategy to promote virulent intracellular growth (24, 54, 55). Interestingly, autophagy is associated only with macrophage killing of the rough M. abscessus morphotype (51). However, in our hands autophagy pathways were not implicated in neutrophil killing of either M. abscessus morphotype. Activation of neutrophil autophagy has been demonstrated in response to rapamycin, Escherichia coli, and Burkholderia pseudomallei (44, 45), although we were unable to detect LC3B expression or localization by M. abscessus or rapamycin using several antibodies.

FIG 9.

Different neutrophil processing pathways for M. abscessus and autophagic cargo. Phagocytic uptake and intracellular processing of M. abscessus are independent of classical autophagy. Rapamycin (rapa) enhances autophagic vesicle formation (open arrow), while azithromycin (AZM) and chloroquine (Cq) prevent autophagosome-lysosome fusion; these agents fail to modify neutrophil killing of M. abscessus. Wortmannin (WT) disrupts autophagic vesicle formation (not shown), but also inhibits M. abscessus killing by reducing phagocytosis. Specific vesicles are indicated in italics; M. abscessus (closed ovals) and autophagic targets (gray squares) are depicted.

Wortmannin inhibits intracellular trafficking pathways, including autophagy, through its inhibition of VPS34. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation by soluble activators has also been reported to be sensitive to wortmannin (56, 57). Interestingly, wortmannin prevented M. abscessus killing (Fig. 2 and 8), and these observations were extended to P. aeruginosa killing (Fig. 3). In macrophages and other cell types, wortmannin inhibits phagocytosis (58–62). However, the role of wortmannin-sensitive pathways in pathogen phagocytosis in neutrophils is less clear. Nakayama et al. demonstrated inhibition of M. intracellulare and M. gordonae uptake by wortmannin in human neutrophils (63). However, other studies failed to associate wortmannin with inhibition of phagocytosis (64, 65). Staphylococcus aureus killing is attenuated by wortmannin, but the effect on phagocytosis was not explored (66). At the concentration used (10 μM), wortmannin is likely targeting PI3Ks other than VPS34 to block uptake. Overall, our studies support a role of wortmannin-sensitive pathway(s) in M. abscessus uptake and killing.

Pathogen recognition and intracellular processing are important steps in controlling infections, but these mechanisms are not well understood for M. abscessus. Mannose-capped lipoarabinomannans (ManLAMs) may be important in blocking M. intracellulare-containing phagosome maturation (63). LAMs and lipomannans are found in mycobacteria, and ManLAM was also identified as a factor that promotes intracellular survival by redirecting M. tuberculosis away from autophagic killing (54). The possibility that a similar pathway regulates M. abscessus recognition or clearance was explored. However, ManLAM or mannan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae did not block neutrophil uptake or killing of M. abscessus (not shown), suggesting different processing pathways for M. abscessus. Lipomannans and LAMs were not identified in M. abscessus (15), although unique structural features of lipomannan and LAM found in the closely related M. chelonae suggest that detection and recognition may differ among mycobacterial species or isolates (67, 68). The role of surface lipids in neutrophil M. abscessus recognition and uptake is a focus of ongoing studies.

Finally, AZM had little effect on release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-8 and CCL4/MIP1β, which are strongly induced. Although AZM is known to inhibit inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β release in other cell systems (33, 69, 70), we have observed only minimal IL-1α and IL-1β release from M. abscessus-infected neutrophils (29, 30). Therefore, AZM does not appear to indirectly modify neutrophil immune responses by cytokine release.

Taken together, we have identified an intracellular M. abscessus clearance pathway in neutrophils that is independent of autophagy. Furthermore, our data indicate that AZM has little anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory activity in M. abscessus-infected neutrophils, either by direct regulation of innate immune responses or by modulating regulatory cytokine secretion. Therefore, nonantibiotic immunomodulatory activities of AZM that act on other cells do not appear to be present in neutrophils (33, 34, 71). The lack of autophagy activation may explain, in part, the limited ability of neutrophils to kill M. abscessus, but the molecular details of putative M. abscessus processing pathways await future experiments. These studies enhance our understanding of M. abscessus clearance and suggest that enhancing specific intracellular trafficking pathways may be therapeutically useful.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (ATCC strain 19977/CIP104356T) was propagated from frozen aliquots in 7H9 broth supplemented with 0.5 g/liter bovine albumin fraction V, 0.2 g/liter dextrose, 0.3 mg/liter catalase (ADC; BD Biosciences), 2% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 3 to 5 days. The smooth (Sm-ATCC) and rough (R-ATCC) morphotypes were isolated from the mixed ATCC 19977 stock. Clinical isolates were obtained from the Culture, Biorepository, and Coordinating Core of the Colorado Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Program at National Jewish Health. Washed cultures were sonicated using six 1-s bursts of a Fisher Sonic Dismembrator 100 at approximately 4 W output to obtain single cells and smaller aggregates, and adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 in PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, corresponding to approximately 1 × 109 CFU/ml. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (strain PAO1) was grown in LB overnight, washed in PBS, and the OD600 adjusted to 1.0, corresponding to approximately 2 × 109 CFU/ml, and further diluted before use.

Neutrophil isolation.

Neutrophils were isolated from healthy volunteers by the plasma Percoll method as previously described (72). Isolated neutrophils were washed and resuspended in Krebs-Ringer phosphate-buffered dextrose (154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 1.1 mM MgSO4, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 0.85 mM NaH2PO4, 2.15 mM Na2HPO4, and 0.2% dextrose). Cells were confirmed to be >98% pure by visual inspection of cytospins. CF neutrophils were isolated from patients without regard for clinical status. Blood was collected into heparin-containing tubes, and neutrophils were separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using Lymphoprep. Briefly, blood tubes were centrifuged for 20 min at 350 × g with no brake to isolate platelet-rich plasma, and the remaining sample diluted 1:1 with 0.9% NaCl. One milliliter of prewarmed 6% dextran was added per 10 ml of diluted blood and allowed to sediment for 30 to 45 min. The top layer of cells from the dextran sedimentation was layered carefully onto 15 to 20 ml of Lymphoprep, and centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min at room temperature with no brake. The cell pellet was resuspended in 9 ml water for 15 sec, 1 ml 10× PBS was added, and immediately centrifuged at 300 × g for 6 min. The cells were washed two times with PBS before experiments.

These studies were approved by the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all neutrophil donors. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Killing assay.

Neutrophils were suspended in RPMI supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 2% pooled heat-inactivated platelet-poor plasma (complete RPMI). Sample tubes contained cells (1 × 106) suspended in complete RPMI and the respective bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 10:1 in a 0.1 ml volume. Neutrophils were preincubated with inhibitors for 20 to 30 min prior to adding bacteria. The following inhibitors were used: azithromycin (AZM; 25 μg/ml), wortmannin (10 μM), chloroquine (5 μg/ml) (56), and rapamycin (500 nM) (44, 45). Tubes were initially centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 1 min and pelleted cells were incubated at 37°C for 5 min to promote bacterium-neutrophil interaction, followed by resuspension and incubation for up to 2 h, as indicated. These experimental conditions promote synchronous, close contact of mycobacteria and neutrophils. Triton X-100 (0.1%) in 0.9% NaCl was added to inactivate neutrophils and aid in mycobacterial dispersion. Following vortex mixing and serial dilutions in saline, samples were plated on 7H10 agar supplemented with OADC and incubated at 37°C. Colonies were counted 3 to 5 days after plating, and compared to colony counts at initiation of infection. P. aeruginosa killing was performed at an MOI of 1:1.

Cytokine and chemokine release.

Secretion of IL-8 and CCL4/MIP1β was determined from cell supernatants after 2 h stimulation with M. abscessus at an MOI of 10:1. Products were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (ELISATech).

Intracellular reactive oxygen species assays.

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured using neutrophils loaded with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA for 20 min; labeled cells were washed and resuspended in complete RPMI and 2 × 105 cells were allowed to settle for 20 min in wells of a black 96-well plate at 37°C in the presence of inhibitors. Cells were incubated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), AZM, chloroquine, or wortmannin. Bacteria were added at an MOI of 10:1, centrifuged at 110 × g for 1 min and placed in a BioTek FL800 plate reader; reads were performed every 5 min for up to 2 h at 37°C at excitation/emission of 485/528. Area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) values were generated using GraphPad Prism 4.0.

Phagocytosis of M. abscessus.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled M. abscessus (FITC-Mab) was prepared by incubating washed M. abscessus with 30 μg/ml FITC in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. FITC-Mab was sonicated, as described above, washed two times, and resuspended in PBS (29). For analyzing bacterial localization by flow cytometry, neutrophils were incubated with FITC-Mab at an MOI of 5:1. Samples were processed as described above in the killing assay with a brief centrifugation and incubation before resuspending the cells, and incubated over a period of 5 to 60 min. Reactions were stopped with an equal volume of ice-cold complete RPMI. Neutrophils were stained with eFluor 450-labeled anti-CD16 (CB16) to identify neutrophils, and fixed in 1% formaldehyde/3% sucrose. To distinguish intracellular and extracellular staining, flow analysis was compared in duplicate samples in both the absence (total staining) and presence (internal staining) of 0.4% trypan blue to quench external FITC; results of total staining are reported, as external staining was minimal (29). Analysis was performed on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (TreeStar). Neutrophils were gated to exclude cellular debris and planktonic and aggregated bacteria.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

For analyzing bacterial localization by microscopy (29), neutrophils were incubated with inhibitors, as indicated, and infected with FITC-Mab for 1 h at an MOI of 10:1; cells were adhered to microscope slides by cytocentrifugation and air dried. Cells were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min, stained overnight with anti-elastase (abcam; ab-21595; 1:100), and visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy after binding of Alexafluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and analyzed by t test. Significance was set at a P value of 0.05. All data sets were normally distributed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded in part by grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to K.C.M. (MALCOL14G0), J.A.N. (NICK14G0), and K.P. (POHL16F0 and NCATS Colorado CTSA), and was supported by resources provided by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Colorado Cystic Fibrosis Research and Development Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pierre-Audigier C, Ferroni A, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Le Bourgeois M, Offredo C, Vu-Thien H, Fauroux B, Mariani P, Munck A, Bingen E, Guillemot D, Quesne G, Vincent V, Berche P, Gaillard JL. 2005. Age-related prevalence and distribution of nontuberculous mycobacterial species among patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 43:3467–3470. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3467-3470.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qvist T, Gilljam M, Jönsson B, Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen-Fangel S, Wang M, Svahn A, Kötz K, Hansson L, Hollsing A, Hansen CR, Finstad PL, Pressler T, Høiby N, Katzenstein TL, Scandinavian Cystic Fibrosis Study Consortium. 2015. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria among patients with cystic fibrosis in Scandinavia. J Cyst Fibros 14:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qvist T, Pressler T, Hoiby N, Katzenstein TL. 2014. Shifting paradigms of nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. Respir Res 15:41. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seddon P, Fidler K, Raman S, Wyatt H, Ruiz G, Elston C, Perrin F, Gyi K, Bilton D, Drobniewski F, Newport M. 2013. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis clinics, United Kingdom, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1128–1130. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.120615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. 2018. Epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial sputum positivity in patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 2010–2014. Annals Am Thorac Soc 15:817–826. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201709-727OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martiniano SL, Sontag MK, Daley CL, Nick JA, Sagel SD. 2014. Clinical significance of a first positive nontuberculous mycobacteria culture in cystic fibrosis. Annals Am Thorac Soc 11:36–44. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201309-310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, Von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Floto RA, US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society, Olivier KN, Saiman L, Daley CL, Herrmann JL, Nick JA, Noone PG, Bilton D, Corris P, Gibson RL, Hempstead SE, Koetz K, Sabadosa KA, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Smyth AR, van Ingen J, Wallace RJ, Winthrop KL, Marshall BC, Haworth CS. 2016. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus recommendations for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 71 (Suppl 1):i1–i22. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diel R, Ringshausen F, Richter E, Welker L, Schmitz J, Nienhaus A. 2017. Microbiological and clinical outcomes of treating non-mycobacterium avium complex nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 152:120–142. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon YS, Koh WJ. 2016. Diagnosis and treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. J Korean Med Sci 31:649–659. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan K, Byrd TF. 2018. Mycobacterium abscessus: shapeshifter of the mycobacterial world. Front Microbiol 9:2642. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honda JR, Alper S, Bai X, Chan ED. 2018. Acquired and genetic host susceptibility factors and microbial pathogenic factors that predispose to nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Curr Opin Immunol 54:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson LB, Nessar R, Kempaiah P, Perkins DJ, Byrd TF. 2011. Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipid prevents respiratory epithelial TLR2 signaling as measured by HbetaD2 gene expression and IL-8 release. PLoS One 6:e29148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberley-Deegan RE, Rebits BW, Weaver MR, Tollefson AK, Bai X, McGibney M, Ovrutsky AR, Chan ED, Crapo JD. 2010. An oxidative environment promotes growth of Mycobacterium abscessus. Free Radic Biol Med 49:1666–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhoades ER, Archambault AS, Greendyke R, Hsu FF, Streeter C, Byrd TF. 2009. Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipids mask underlying cell wall phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides blocking induction of human macrophage TNF-alpha by preventing interaction with TLR2. J Immunol 183:1997–2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampaio EP, Elloumi HZ, Zelazny A, Ding L, Paulson ML, Sher A, Bafica AL, Shea YR, Holland SM. 2008. Mycobacterium abscessus and M. avium trigger Toll-like receptor 2 and distinct cytokine response in human cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 39:431–439. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0413OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin DM, Yang CS, Yuk JM, Lee JY, Kim KH, Shin SJ, Takahara K, Lee SJ, Jo EK. 2008. Mycobacterium abscessus activates the macrophage innate immune response via a physical and functional interaction between TLR2 and dectin-1. Cell Microbiol 10:1608–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernut A, Herrmann JL, Kissa K, Dubremetz JF, Gaillard JL, Lutfalla G, Kremer L. 2014. Mycobacterium abscessus cording prevents phagocytosis and promotes abscess formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E943–E952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321390111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrd TF, Lyons CR. 1999. Preliminary characterization of a Mycobacterium abscessus mutant in human and murine models of infection. Infect Immun 67:4700–4707. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.9.4700-4707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catherinot E, Clarissou J, Etienne G, Ripoll F, Emile JF, Daffe M, Perronne C, Soudais C, Gaillard JL, Rottman M. 2007. Hypervirulence of a rough variant of the Mycobacterium abscessus type strain. Infect Immun 75:1055–1058. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00835-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard ST, Rhoades E, Recht J, Pang X, Alsup A, Kolter R, Lyons CR, Byrd TF. 2006. Spontaneous reversion of Mycobacterium abscessus from a smooth to a rough morphotype is associated with reduced expression of glycopeptidolipid and reacquisition of an invasive phenotype. Microbiology 152:1581–1590. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rottman M, Catherinot E, Hochedez P, Emile JF, Casanova JL, Gaillard JL, Soudais C. 2007. Importance of T cells, gamma interferon, and tumor necrosis factor in immune control of the rapid grower Mycobacterium abscessus in C57BL/6 mice. Infect Immun 75:5898–5907. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00014-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim BR, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Kim BJ. 2019. Phagosome escape of rough Mycobacterium abscessus strains in murine macrophage via phagosomal rupture can lead to type I interferon production and their cell-to-cell spread. Front Immunol 10:125. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S-W, Subhadra B, Whang J, Woo Y, Hyun B, Bae S, Kim H-W, Choi CH. 2017. Clinical Mycobacterium abscessus strain inhibits autophagy flux and promotes its growth in murine macrophages. Pathog Dis 75:ftx107. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biswas D, Qureshi OS, Lee WY, Croudace JE, Mura M, Lammas DA. 2008. ATP-induced autophagy is associated with rapid killing of intracellular mycobacteria within human monocytes/macrophages. BMC Immunol 9:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu CH, Liu H, Ge B. 2017. Innate immunity in tuberculosis: host defense vs pathogen evasion. Cell Mol Immunol 14:963–975. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genestet C, Lyon TB study group, Bernard-Barret F, Hodille E, Ginevra C, Ader F, Goutelle S, Lina G, Dumitrescu O, Lyon T. 2018. Antituberculous drugs modulate bacterial phagolysosome avoidance and autophagy in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 111:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan ED, Bai X, Kartalija M, Orme IM, Ordway DJ. 2010. Host immune response to rapidly growing mycobacteria, an emerging cause of chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43:387–393. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0276TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malcolm KC, Caceres SM, Pohl K, Poch KR, Bernut A, Kremer L, Bratton DL, Herrmann JL, Nick JA. 2018. Neutrophil killing of Mycobacterium abscessus by intra- and extracellular mechanisms. PLoS One 13:e0196120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malcolm KC, Nichols EM, Caceres SM, Kret JE, Martiniano SL, Sagel SD, Chan ED, Caverly L, Solomon GM, Reynolds P, Bratton DL, Taylor-Cousar JL, Nichols DP, Saavedra MT, Nick JA. 2013. Mycobacterium abscessus induces a limited pattern of neutrophil activation that promotes pathogen survival. PLoS One 8:e57402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feola DJ, Garvy BA, Cory TJ, Birket SE, Hoy H, Hayes D Jr, Murphy BS. 2010. Azithromycin alters macrophage phenotype and pulmonary compartmentalization during lung infection with Pseudomonas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2437–2447. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01424-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain S, Varelogianni G, Sarndahl E, Roomans GM. 2015. N-acetylcysteine and azithromycin affect the innate immune response in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells in vitro. Exp Lung Res 41:251–260. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2014.934411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gualdoni GA, Lingscheid T, Schmetterer KG, Hennig A, Steinberger P, Zlabinger GJ. 2015. Azithromycin inhibits IL-1 secretion and non-canonical inflammasome activation. Sci Rep 5:12016. doi: 10.1038/srep12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann P, Ziesenitz VC, Curtis N, Ritz N. 2018. The immunomodulatory effects of macrolides—a systematic review of the underlying mechanisms. Front Immunol 9:302. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nozoe K, Aida Y, Fukuda T, Sanui T, Nishimura F. 2016. Mechanisms of the macrolide-induced inhibition of superoxide generation by neutrophils. Inflammation 39:1039–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silvestri M, Oddera S, Eftimiadi C, Rossi GA. 1995. Azithromycin induces in vitro a time-dependent increase in the intracellular killing of Staphylococcus aureus by human polymorphonuclear leucocytes without damaging phagocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother 36:941–950. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyazaki M, Zaitsu M, Honjo K, Ishii E, Hamasaki Y. 2003. Macrolide antibiotics inhibit prostaglandin E2 synthesis and mRNA expression of prostaglandin synthetic enzymes in human leukocytes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 69:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bystrzycka W, Manda-Handzlik A, Sieczkowska S, Moskalik A, Demkow U, Ciepiela O. 2017. Azithromycin and chloramphenicol diminish neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) release. Int J Mol Sci 18:2666. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai PC, Schibler MR, Walters JD. 2015. Azithromycin enhances phagocytic killing of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Y4 by human neutrophils. J Periodontol 86:155–161. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renna M, Schaffner C, Brown K, Shang S, Tamayo MH, Hegyi K, Grimsey NJ, Cusens D, Coulter S, Cooper J, Bowden AR, Newton SM, Kampmann B, Helm J, Jones A, Haworth CS, Basaraba RJ, DeGroote MA, Ordway DJ, Rubinsztein DC, Floto RA. 2011. Azithromycin blocks autophagy and may predispose cystic fibrosis patients to mycobacterial infection. J Clin Invest 121:3554–3563. doi: 10.1172/JCI46095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binder AM, Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. 2013. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections and associated chronic macrolide use among persons with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:807–812. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1200OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moriya S, Che XF, Komatsu S, Abe A, Kawaguchi T, Gotoh A, Inazu M, Tomoda A, Miyazawa K. 2013. Macrolide antibiotics block autophagy flux and sensitize to bortezomib via endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated CHOP induction in myeloma cells. Int J Oncol 42:1541–1550. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukai S, Moriya S, Hiramoto M, Kazama H, Kokuba H, Che X-F, Yokoyama T, Sakamoto S, Sugawara A, Sunazuka T, Ōmura S, Handa H, Itoi T, Miyazawa K. 2016. Macrolides sensitize EGFR-TKI-induced non-apoptotic cell death via blocking autophagy flux in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol 48:45–54. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitroulis I, Kourtzelis I, Kambas K, Rafail S, Chrysanthopoulou A, Speletas M, Ritis K. 2010. Regulation of the autophagic machinery in human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol 40:1461–1472. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rinchai D, Riyapa D, Buddhisa S, Utispan K, Titball RW, Stevens MP, Stevens JM, Ogawa M, Tanida I, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Ato M, Lertmemongkolchai G. 2015. Macroautophagy is essential for killing of intracellular Burkholderia pseudomallei in human neutrophils. Autophagy 11:748–755. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1040969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosnar M, Kelneric Z, Munic V, Erakovic V, Parnham MJ. 2005. Cellular uptake and efflux of azithromycin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, telithromycin, and cethromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2372–2377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2372-2377.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolter J, Seeney S, Bell S, Bowler S, Masel P, McCormack J. 2002. Effect of long term treatment with azithromycin on disease parameters in cystic fibrosis: a randomised trial. Thorax 57:212–216. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saiman L, Anstead M, Mayer-Hamblett N, Lands LC, Kloster M, Hocevar-Trnka J, Goss CH, Rose LM, Burns JL, Marshall BC, Ratjen F, AZ0004 Azithromycin Study Group. 2010. Effect of azithromycin on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis uninfected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 303:1707–1715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Principi N, Blasi F, Esposito S. 2015. Azithromycin use in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34:1071–1079. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cullinane M, Gong L, Li X, Lazar-Adler N, Tra T, Wolvetang E, Prescott M, Boyce JD, Devenish RJ, Adler B. 2008. Stimulation of autophagy suppresses the intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in mammalian cell lines. Autophagy 4:744–753. doi: 10.4161/auto.6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roux AL, Viljoen A, Bah A, Simeone R, Bernut A, Laencina L, Deramaudt T, Rottman M, Gaillard JL, Majlessi L, Brosch R, Girard-Misguich F, Vergne I, de Chastellier C, Kremer L, Herrmann JL. 2016. The distinct fate of smooth and rough Mycobacterium abscessus variants inside macrophages. Open Biol 6:160185. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bah A, Lacarriere C, Vergne I. 2016. Autophagy-related proteins target ubiquitin-free mycobacterial compartment to promote killing in macrophages. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6:53. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manzanillo PS, Ayres JS, Watson RO, Collins AC, Souza G, Rae CS, Schneider DS, Nakamura K, Shiloh MU, Cox JS. 2013. The ubiquitin ligase parkin mediates resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature 501:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fratti RA, Chua J, Vergne I, Deretic V. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycosylated phosphatidylinositol causes phagosome maturation arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:5437–5442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737613100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma V, Verma S, Seranova E, Sarkar S, Kumar D. 2018. Selective autophagy and xenophagy in infection and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 6:147. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Germic N, Stojkov D, Oberson K, Yousefi S, Simon HU. 2017. Neither eosinophils nor neutrophils require ATG5-dependent autophagy for extracellular DNA trap formation. Immunology 152:517–525. doi: 10.1111/imm.12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manfredi AA, Rovere-Querini P, D'Angelo A, Maugeri N. 2017. Low molecular weight heparins prevent the induction of autophagy of activated neutrophils and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Pharmacol Res 123:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khelef N, Shuman HA, Maxfield FR. 2001. Phagocytosis of wild-type Legionella pneumophila occurs through a wortmannin-insensitive pathway. Infect Immun 69:5157–5161. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.5157-5161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Araki N, Johnson MT, Swanson JA. 1996. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the completion of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis by macrophages. J Cell Biol 135:1249–1260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allen LA, Allgood JA, Han X, Wittine LM. 2005. Phosphoinositide3-kinase regulates actin polymerization during delayed phagocytosis of Helicobacter pylori. J Leukoc Biol 78:220–230. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee HJ, Ko HJ, Song DK, Jung YJ. 2018. Lysophosphatidylcholine promotes phagosome maturation and regulates inflammatory mediator production through the protein kinase A-phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mouse macrophages. Front Immunol 9:920. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tachado SD, Samrakandi MM, Cirillo JD. 2008. Non-opsonic phagocytosis of Legionella pneumophila by macrophages is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. PLoS One 3:e3324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakayama H, Kurihara H, Morita YS, Kinoshita T, Mauri L, Prinetti A, Sonnino S, Yokoyama N, Ogawa H, Takamori K, Iwabuchi K. 2016. Lipoarabinomannan binding to lactosylceramide in lipid rafts is essential for the phagocytosis of mycobacteria by human neutrophils. Sci Signal 9:ra101. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santoro P, Cacciapuoti C, Palumbo A, Graziano D, Annunziata S, Capasso L, Formisano S, Ciccimarra F. 1998. Effects of wortmannin on human neutrophil respiratory burst and phagocytosis. Ital J Biochem 47:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giraldo E, Martin-Cordero L, Hinchado MD, Garcia JJ, Ortega E. 2010. Role of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and nuclear transcription factor kappa beta (NF-k beta) on neutrophil phagocytic process of Candida albicans. Mol Cell Biochem 333:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schnyder B, Meunier PC, Car BD. 1998. Inhibition of kinases impairs neutrophil activation and killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J 331:489–495. doi: 10.1042/bj3310489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guerardel Y, Maes E, Elass E, Leroy Y, Timmerman P, Besra GS, Locht C, Strecker G, Kremer L. 2002. Structural study of lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan from Mycobacterium chelonae. Presence of unusual components with alpha 1,3-mannopyranose side chains. J Biol Chem 277:30635–30648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guirado E, Arcos J, Knaup R, Reeder R, Betz B, Cotton C, Patel T, Pfaller S, Torrelles JB, Schlesinger LS. 2012. Characterization of clinical and environmental Mycobacterium avium spp. isolates and their interaction with human macrophages. PLoS One 7:e45411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fan LC, Lin JL, Yang JW, Mao B, Lu HW, Ge BX, Choi AMK, Xu JF. 2017. Macrolides protect against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection via inhibition of inflammasomes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 313:L677–L686. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00123.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lendermon EA, Coon TA, Bednash JS, Weathington NM, McDyer JF, Mallampalli RK. 2017. Azithromycin decreases NALP3 mRNA stability in monocytes to limit inflammasome-dependent inflammation. Respir Res 18:131. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borkner L, Misiak A, Wilk MM, Mills K. 2018. Azithromycin clears Bordetella pertussis infection in mice but also modulates innate and adaptive immune responses and T cell memory. Front Immunol 9:1764. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haslett C, Guthrie LA, Kopaniak MM, Johnston RB Jr, Henson PM. 1985. Modulation of multiple neutrophil functions by preparative methods or trace concentrations of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Pathol 119:101–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]