Abstract

Indole and six simple analogues were crystallized in different environments to study the crystal habit changes. All crystal structures were determined by X-ray diffraction experiments. Lattice energies based on DFT-D3 periodic calculations and framework analysis were used to define the most important intermolecular interactions in the crystal structures: N–H···π (−28 kJ/mol), hydrogen bonds (−34 kJ/mol), π···π stacking interactions (−18 kJ/mol), and dipole–dipole (−18 kJ/mol). As morphology is an important feature in many industrial applications, such as photovoltaic cells, electronic devices, and drug discovery, we predicted the crystal morphology of selected crystals using the BFDH and AE models. Facet character depends on the orientation of the molecules at the surface and is therefore sensitive to the variation of crystallization conditions such as solvent, method, and temperature. All indole derivatives tend to form plate crystals with the largest {002} facet. We showed that the morphological importance of the {002} facet increases, whereas the {011} facet decreases with solvent polarity for 5-nitroindole and 4-cyanindole crystals, resulting in a change of crystal habit from needle to plate and from plate to prism, respectively.

Introduction

Indole (Figure 1a) is the parent substance of a large number of important compounds that occur in nature. The indole moiety is embedded in many biological systems including the essential amino acid tryptophan. Tryptophan is a structural constituent of many proteins as well as the biosynthetic precursor of serotonin, which, in turn, serves as the precursor of melatonin. Serotonin plays a critical role in neuronal cell formation and maintenance, as well as regulating sleep, cognition, appetite, and mood,1 while melatonin is a natural bioregulator that induces and maintains sleep.2

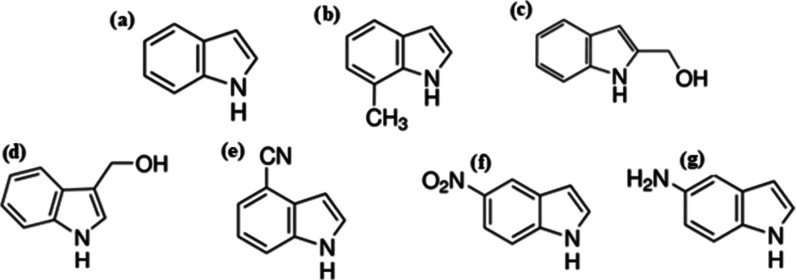

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of indole (I): (a) and indole derivatives; (b) 7-methyloindole (7MI); (c) 1H-indole-2-methanol (I2M); (d) indole-3-carbinol (I3C); (e) 4-cyanoindole (4CI); (f) 5-notroindole (5NI); and (g) 5-aminoindole (5AI).

The indole moiety is also ubiquitous in biologically active alkaloids such as the first plant-derived agents to advance into clinical use, the so-called vinca alkaloids,3 vinblastine, and vincristine. A number of indole-containing compounds have been brought to the market. Among them, sumatriptan, ondansetron, tadalafil, ziprasidone, and sunitinib have enjoyed great clinical and commercial success, thus making this class of drugs an integral part of the arsenal against various diseases.

Recent medicinal chemistry efforts have generated several investigational drugs bearing indole scaffold, and these compounds have shown great promise in curing certain types of cancer and central nervous system disorders. Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) is a hydrolysis product of glucobrassicin, both of which are found in high concentrations in cruciferous vegetables. Studies have shown a correlation between diets high in cruciferous vegetables and the reduced incidence of several cancer types.4,5 I3C may have utility as a cancer therapeutic agent as shown in a small clinical trial in women with biopsy-proven cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.6 As the indole scaffold has become an important structural subunit for drug discovery, more indole-containing drugs are likely to be unearthed in the future.

In recent decades, researchers in crystal engineering have studied the crystal structures of related molecules to find a correlation between molecular structure and crystal packing with the ultimate goal of rationally designing crystal properties. Understanding and controlling the shape of crystals can enable active ingredients to be processed into viable products. The first model to predict the crystal morphology was the BFDH model, which is a nonmechanistic method proposed by Bravais, Friedel, Donnay, and Harker7−10 under the well-known Frank–Chernov condition.10,11 Later, Hartman and Bennema12 developed the attachment energy (AE) model, which enhanced the accuracy of predicting the crystal growth rates of the crystal faces by taking solid-state interactions into account. The AE model is generally an improvement on the BFDH model but still fails to consider the impacts of supersaturation, solvents, and additives.13,14 They are often used in pharmaceutical crystallization to modify the crystal habit15−17 or to stabilize metastable polymorph.18,19 Therefore, a new modified attachment energy (MAE) model has been developed to show that the crystal aspect ratios were sensitive to the relative polarity of the solvents.20−22 Nonetheless, morphological prediction using the AE theory gives a good prediction for crystals grown at low driving forces.23−26 This method, combined with the analysis of the interaction energy and surface chemistry, can result in understanding the formation of the undesired crystal habits.27−29 The AE model relies on the correct calculation of the interaction energy and should be based on state-of-the-art methods. Most predictions mentioned above use the classical force-field method. An attempt to predict the crystal morphology based on dispersion-corrected DFT (DFT-D) results have already been reported.30,31 However, the study of the solvent–crystal interaction from the thermodynamic perspective is just a partial picture. Therefore, the implementation of the molecular dynamics (MD) helps to investigate the directions of the crystal growth with molecular information, revealing the interactions between the solvent molecules and the crystal surfaces and provide more microscopic details for the experiments. The MD method has been successfully applied to simulate the crystal morphology in many cases.32−35

Morphology prediction and screening are, therefore, important to obtain desirable shapes for filtering and downstream processing. This study is aimed at analyzing the crystal structure analysis of indole and its analogues to understand the relationship between the crystal habit and intermolecular interactions in the crystal. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of solvent on the crystal habit, which may favor a better understanding of the crystal morphologies, especially the aspect ratio changes of the crystal shapes.

Results and Discussion

Crystal Structures

Indole (I)

Indole crystallizes in the orthorhombic system in the Pna21 space group. The crystal structure was previously reported;36 however, the coordinate parameters are not present in the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). We have remeasured the structure of indole on a crystal grown from hexane of size 0.5 mm × 0.3 mm × 0.05 mm, showing a platelike shape. The space group was confirmed as the one in the 1975 reported structure, as well as the orientational disorder of the indole molecule in the crystal. The disorder consists of a 180° flip of the molecule that sits on the same general crystallographic position. In particular, the C8 atom is the only one that keeps almost the same coordinates in the two molecular orientations (Figure 2). The strongest interactions in the indole structure are N−H···π type contacts with the shortest distance of 3.41(1) Å between N(1) and C(3) (Figure 3a). The angle between the indole planes is 60.04(1)°. This type of dimer is referred to as a D1 (Figure 4). Each molecule also forms C−H···π contacts (D2). D1 and D2 contacts are typical of the herringbone packing arrangement, as shown in Figure 3b. Those interactions, in turn, form zigzag chain in the [100] and [010] directions, forming molecular layers. Every second molecule in the chains also interacts by the π···π stacking with 2.765 Å distance (D3). Each layer interacts via weak dispersion interaction.

Figure 2.

Two orientations of indole molecules in the crystal structure. ADP was drawn at 50% probability.

Figure 3.

Crystal packing of I molecules: (a) view along the [010] and (b) view along the [001]. N–H···π, C–H···π, and π···π contacts are shown as green, cyan, and orange dashed lines, respectively.

Figure 4.

Visualization of selected dimers (a) D1, (b) D2, (c) D3, (d) D4, (e) D5, and (f) D6 used in the discussion of interactions and packing of the crystal structures.

7-Methylindole (7MI)

7-Methylindole(7MI) crystallizes in the space group Pna21 (Figure 5). The structure of 7MI also shows orientational disorder in the ratio 54–46%. As with the I structure, the molecules form a layer structure with the D1, D2, and D3 interactions. The energy frameworks analysis shows (Figures S6 and S7, SI) a remarkable similarity in the topologies corresponding to the I and 7MI structures, these two crystals are isostructural.

Figure 5.

Two orientations of the 7MI molecule in the crystal structure. Atom labels are only present for the first orientation. The second orientation has the same labels with the A index. Anisotropic ADPs are drawn at 50% probability.

1H-Indole-2-methanol (I2M)

1H-Indole-2-methanol crystallizes in a monoclinic system in the P2/c space group. The asymmetrical part of the unit cell contains two molecules with different hydroxyl group orientations, defined by the N1–C2–C10–O1 torsion angle of 61.5(3)° (gauche+ conformation) and −175.5(2)° (trans conformation) (Figure 6). The structure has a disorder related to two possible positions of the hydrogen atoms at O1 and O1A. The disorder is located around the crystallographic twofold symmetry axis. Therefore, the occupation factor for the hydrogen atoms is fixed at 0.5. Both molecular conformations are not the most stable, as found in relative energy calculation for the N1–C2–C10–O1 torsion angle, which showed the gauche–, with an angle of −66°, to be the most stable (Supporting Information, Figure S17).

Figure 6.

Molecular structure of I2M and atom labeling scheme. ADPs are shown at 50% probability level.

Each molecule interacts with the second molecule via hydrogen bonds forming the D4 dimer (Figure 4). The shortest distance is 2.662(3) Å between the O1A···O1A1–x,1–y,1–z, forming the O1A–H1AA···O1A1–x,1–y,1–z hydrogen bond. These interactions are arranged in the crystal structure along the [001] direction, forming an infinite chain of hydrogen bonds (Figure 7). As a result of the H atoms disorder, there are two possible orientations of the interactions: up and down when viewing the crystal structure along the [010] axis. Every second molecule in the chain connects also via the N–H···π (D1) and C–H···π interactions (D2). The last type of interaction that is important for the crystal structure is the π···π stacking (D3). However, molecules are shifted as presented in Figure 4c.

Figure 7.

Crystal packing in the I2M view along the [010] direction. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines, whereas the N–H···π interactions are shown as green dashed lines.

Indole-3-carbinol (I3C)

Similar to the previous crystal structure, the I3C molecules (Figure S2, SI) form a layered structure in the P21/c space group. Here, three molecules are part of the asymmetric unit with different orientations of the hydroxyl group with the C2–C3–C10–O1 torsion angle equal to −123.7(4), −84.0(4), and 98.4(4)°, respectively. Viewing the crystal structure along the [001] axis, the molecules form a characteristic layered motif (Figure 8). It is held together by the N–H···π (D1) and π···π (D3) interactions that form a herringbone packing (face-to-edge) with adjustment molecules connected via the π···π stacking (Figure 8a). The presence of hydroxyl groups allows the formation of classic hydrogen bonds stabilizing the structure in the direction of the [010] (between layers) (Figure 8b). Hydrogen bonds form a ribbon along the [001] axis with a repeating sequence: O(1B)–H(1Ba)···O(1)–H(1A)···O(1A)–H(1Ab)···O(1B).

Figure 8.

Crystal packing of I3C molecules: (a) view along the [010] axis and (b) view along the [001] axis. Hydrogen bonds and N–H···π contacts are shown as yellow and green dashed lines, respectively.

5-Aminoindole (5AI)

The 5AI molecule crystallizes in the space group Pna21 (Figure S3, SI). Similar to the indole derivatives with the hydroxyl group, the 5AI molecule has an amino group that can be an acceptor and a donor of hydrogen bonds. However, the N(1) atom of the five-membered ring is a better donor and the N(1)–H(1)···N(2) is formed (D5), whereas the hydrogen atoms of the amino group form two N–H···π contacts (D1′). The strongest interaction forms a characteristic chain of hydrogen bonds along the [010] direction (Figure 9). Molecules that are acceptors of the N–H···N hydrogen bond act as hydrogen donors in two N–H···π interactions with the contact distance N(2)···C(6) and N(2)···C(8) with 3.471(2) and 4.565(2) Å, respectively.

Figure 9.

Crystal packing of 5AI molecules along the [001] axis. Hydrogen bonds and N–H···π contacts are shown as yellow and green dashed lines, respectively.

4-Cyanoindole (4CI)

4CI crystallizes in an orthorhombic system in the P212121 space group (Figure S4, SI). The nitrogen atom from the cyano group takes part in the N(1)–H(1)···N(2) hydrogen bond (D5) that forms a chain of interactions in the [110] direction. It is characterized by the following geometric parameters: the N(1)···N(2) distance is 3.011(2) Å, while the angle between the N(1)–H(1)···N(2) is 159.8(1)°. The second chain is formed jointly with the opposite orientation of the molecules (Figure 10). The two closest moieties at these chains can be identified as the new D6 dimer. It is an example of the dipole–dipole interaction. Such an interaction is possible because of the charge distribution, resulting in a nonzero molecular dipole moment. In the [100] direction, molecules form columns with the aid of the π···π stacking.

Figure 10.

Crystal packing of 4CI molecule view along the [100] axis. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines.

5-Nitroindole (5NI)

The 5NI molecules crystallize in a monoclinic system in the P21/c group. In the 5-nitroindole structure, as a result of the presence of the oxygen atom acceptors and N–H hydrogen bond donors, the molecules are stabilized in the [001] direction through the N–H···O hydrogen bonds (D5) (Figure 11). In addition to hydrogen bond chains, the molecules forming adjoined chains have opposite orientation and, as a consequence, pairs of molecules interact via dipole–dipole interactions (D6). Along the [100] direction, molecules form stacks. The displacement of molecules against each other allows the formation of π···π interactions. The length of a given interaction is 3.335(2) Å, if we count it as the distance between the mean planes of the indole molecules.

Figure 11.

Crystal packing of 5NI molecule view along the [100] axis. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines.

Dimer Interactions

Crystal packing analysis revealed similarities and differences between intermolecular interactions in the crystal structures. During structural analysis, six key dimers were distinguished that stand for N–H···π, C–H···π, π···π, O–H···O, N–H···[O, N], and dipole–dipole interaction (Figure 4). Not every dimer is present in all structures. The crystal-specific interactions and their total energies were calculated with the aid of CrystalExplorer program,37 also electrostatic and dispersion contributions are presented in Table 1. The obtained values of interaction energies can be used to construct the three-dimensional topology of interactions, which are termed as energy frameworks (SI, Figures S6–S10).

Table 1. Interaction Energies for Selected Dimers (D1–D6) Present in the Analyzed Crystalsa.

| crystal | dimer | EelCE [kJ/mol] | EdisCE [kJ/mol] | EtotCE [kJ/mol] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | D1 | –12.3 | –25.1 | –28.1 |

| D2 | –1.5 | –21.4 | –13.4 | |

| D3 | –6.2 | –14.9 | –16.4 | |

| 7MI | D1 | –13.2 | –24.8 | –28.0 |

| D2 | –0.8 | –18.8 | –12.9 | |

| D3 | –6.3 | –21.3 | –19.7 | |

| I3C | D1 | –15.6 | –29.2 | –34.4 |

| D1 | –15.9 | –26.6 | –32.8 | |

| D2 | –10.0 | –27.6 | –25.4 | |

| D2 | –5.2 | –24.0 | –19.6 | |

| D3 | –3.9 | –17.2 | –15.9 | |

| D3 | –3.0 | –14.1 | –13.9 | |

| D4 | –24.4 | –13.7 | –24.4 | |

| D4 | –23.5 | –12.2 | –22.0 | |

| 5AI | D1′ | –11.5 | –24.2 | –24.0 |

| D1′ | –2.1 | –26.4 | –16.2 | |

| D3 | –4.9 | –12.4 | –9.6 | |

| D5 | –37.5 | –13.9 | –33.0 | |

| D6 | –7.2 | –12.5 | –14.1 | |

| 4CI | D3 | 6.1 | –41.2 | –16.1 |

| D5 | –39.0 | –6.1 | –33.8 | |

| D6 | –9.4 | –11.6 | –15.8 | |

| 5NI | D3 | 4.7 | –47.3 | –17.9 |

| D3/6 | –16.0 | –11.5 | –22.9 | |

| D3/6 | –10.3 | –18.9 | –21.0 | |

| D3/6 | –10.9 | –9.7 | –17.9 | |

| D5 | –41.4 | –9.7 | –37.8 |

ECE represents the interaction energies computed with CrystalExplorer.37EelCE, Edis, and EtotCE are the electrostatic, dispersive, and total interaction energies, respectively.

The structures of I and 7MI form an isostructural network. In all directions, it creates similar packing motifs, dominated by dispersion interaction (D1 and D2). The D1 has a small electrostatic contribution, which is an example of the weak interaction of the hydrogen bonding type. The D1 dimer forms a characteristic motif (Figure 4) with two molecules stacking at certain angles in the I, 7MI, I2M, I3C, and 5AI structures (“herringbone” motif). The angles between the indole ring plane are in the range between 60 and 85°. However, the interaction energy is around −28 kJ/mol, suggesting a weak directional character. A stronger interaction was found for the I3C structure, where the hydroxymethyl contributes to stabilizing of donor properties of the indole group. In all of these structures, the D1 is the strongest interaction, which can be even stronger than classical hydrogen bonds found in the I3C structure (D4). The presence of the D1 interaction induces the second interaction (C−H···π, D2) and both lead to the formation of the layered packing in structures. The layers are formed in the direction of the (002) in I, 7MI, and I2M but in the (010) direction in the I3C. For hydroxymethyl derivatives between the layers formed by the D1 and D2, there are alternate interactions of hydrogen bonds (D4 and very weak interactions (H···H)) (see Figures 7 and 8).

Introducing a strong acceptor as a cyano, nitro, or amino group results in the formation of different crystal packing with hydrogen bonding motifs (D5). The hydrogen bond interaction energies are −33.8, −37.8, and −33 kJ/mol for 5CI, 5NI, and 5AI, respectively. Here, electrostatic forces provide a much greater contribution to the interaction energy. They represent the strongest interaction. The structures form infinite hydrogen bond chains that are parallel to the (002) plane for 4CI, the (102̅) plane for 5NI, and the zigzag chain in the [110] direction for 5AI. High dipole moments of the 5NI and 4CI molecules result in the formations of dipole–dipole interactions that connect the hydrogen-bonded chains (see Figures 11 and 10). Furthermore, the 4CI and 5NI structures are similar viewing energy framework along the [010] structures, showing the similar placement of hydrogen bond and dipole–dipole interactions (SI, Figure S9). The situation is different for the 5AI structure. The two hydrogens of the amino group form the N–H···π interaction (D1′), which is the second strongest interaction connecting the zigzag chains.

Lattice Energy of Crystal Structures

Lattice energies for indole derivative structures are within the limits of −230.8 to −162.2 kJ/mol (Table 2). The lowest lattice energy was found for the I3C. The highest energy had the I structure. Although I and 7MI are isostructural structures, the difference in the lattice energies is about 22 kJ/mol, which is because of the more stabilizing nature of the D2 dimer in the latter. For the two orientations of the same molecule, the difference in the lattice energies is practically negligible. There is a linear correlation between the melting point and the lattice energy with the exception of I3C, which has a melting point of 96 °C, with the lowest energy of the lattice energy.

Table 2. Lattice Energy Values (Elat) Computed for Optimized Crystal Structures Using CRYSTAL and Melting Point (Mp [°C])a.

| crystal | part | Elatt [kJ/mol] | Mp [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | –162.2 | 51 |

| 2 | –162.2 | ||

| 7MI | 1 | –184.5 | 80 |

| 2 | –184.5 | ||

| I3C | –230.8 | 96 | |

| 5AI | –206.6 | 131 | |

| 4CI | –204.5 | 117 | |

| 5NI | –223.5 | 140 |

Note that the energies are given per one molecule in the unit cell. For the disordered structures, both orientations were calculated and referenced as Parts 1 and 2.

Crystal Habit

Morphology prediction was performed for the crystals I3C, 5AI, 4CI, and 5NI structures. Two crystals of I3C, four 4CI crystals, six 5NI, and four 5AI crystals obtained from different solvents were used to consider the effect of the crystallization conditions on the morphology.

I, which crystallizes from hexane, only solvent that produces monocrystals of good quality, grows as flat crystals with the {002} as the largest facets (SI, Figure S1). The perpendicular facets to this one are poorly formed and difficult to index. This is a result of the strongest interactions taking part in the formation of a layer structure with D1–D3 interactions and weak interactions between layers of −5 kJ/mol (SI, Table S2).

The morphology of the actual indole-3-carbinol crystal is different from the habit predictions (Table 3). The reason could be a problem with the lattice energy calculation. The obtained I3C crystals grow as plates with the (010) facet with morphology importance (MI) higher than 80% (SI, Figure S12).

Table 3. Crystal Structure Information and the Morphology of I3C, 5AI, 4CI, and 5NI Crystals Predicted by the BFDH Model (Blue) and the AE Model (Green).

5AI crystallizes only from polar solvents, DCM, and alcohol. It forms bulky crystals; however, those crystallized from alcohols are flattened in a direction with the largest {112} facet for butanol and ethanol and the {101} crystallized from the ethanol/hexane by the vapor diffusion method (SI, Figure S13).

In Table 3, it can be seen that the BFDH models are similar for crystals with the same shortest unit cell parameter. For 4CI and 5NI crystals, the facets along the [100] axis grow the fastest (a cell parameter for both crystals is the shortest parameter). For the crystal habit predicted by the BFDH model, the I3C and 5AI crystals, the growth direction [001] is favored. The {011} facets are the most important for the 5NI crystal (MI = 60%). For 5NI, both models predict the {011} as the most important facet with MI of 64 and 68%, respectively. In addition, for the AE model, the {102̅} facet (MI = 28%) is the second most important and is practically nonexistent in the BFDH model. For 4CI, the predicted crystal habit model based on the attachment energies has the shape of a flattened disk with the slowest and most important {002} facets (MI = 84%).

In the crystallization experiments, three crystals of 4CI were obtained using various types of solvents (Figure 12). With crystallization solvent polarity, the 4CI crystal shape changes from plate to prism. All three crystals contain facets that were predicted by theoretical models. The attachment energy of the {002} facet is related to the D6 dimer, which is the weakest interaction between the molecules in the 4CI crystal structure (Figure 13a). Therefore, the facet has a high MI for the three crystals. Essential facets for the crystal obtained from DCM are the {011} that cut through the dimers D5 and D6 (Figure 13b). These facets have a hydrophilic layer with donors and acceptors available on the surface that can form hydrogen bonds with the chloride atoms present in the solvent molecule, which causes the facet’s growth to stop and increase its significance.

Figure 12.

Morphology of 4CI recrystallized in (a) chloroform; (b) dichloromethane (DCM); and (c) diethyl ether.

Figure 13.

Selected slices of the most morphologically important facet of the 4CI (a, b) and 5NI (c, d) crystal structures. First column shows the {002} planes and the left column the {011} planes.

In all obtained crystals of 5NI, the longest crystal axis is the [100] (Figure 14), which harmonizes well with the morphology model based on the unit cell parameters. Experimentally obtained crystals from toluene, DCM, and acetonitrile have a shape similar to the needle, while the crystals grown from diethyl ether, THF, and ethanol are plates with the {002} facet as a major contribution to the total surface area. Overall, the {002} facets dominate the crystals crystallized from solvents with higher polarity. For needle crystals, the {002} facets have the highest significance as well. However, in these cases, the {011} planes are also important. Inside the {002} layer, there is a D3 dimer and the D6 interactions are broken, orienting the molecules in such a way that NH groups are on the outside of the layer (Figure 13c). Therefore, it is possible to form hydrogen bonds with the acceptors present in the solvent molecules. For solvents with higher polarity, these interactions are stronger, so the facet growth is inhibited and their significance is higher. For the 5NI crystal crystallized from DCM, in the molecule of which there are two hydrogen bond acceptors, the {002} facets have the largest surface, which translates into high morphological significance of 99%. In addition, analyzing the physiochemical properties of individual solvents, one can note the following relationship: for crystals crystallized from solvents with a higher dielectric constant, the morphological significance of the {002} facets increase and that of the {011} facets decrease. For solvents with a low boiling point, the most important are the {002} facets.

Figure 14.

Morphology of 5NI recrystallized in (a) toluene; (b) diethyl ether; (c) tetrahydrofuran (THF); (d) DCM; (e) ethanol; and (f) acetonitrile.

Conclusions

In this work, the crystal structures of indole and six of its derivatives were characterized in terms of their intermolecular interactions and the characteristic packing motifs using X-ray diffraction measurements on crystals grown from solution by evaporation or vapor diffusion methods. Indole, 7-methylindole, indole-3-carbinol, 4-cyanoindole, and 5-aminoindole crystallize in the orthorhombic system, while 1H-indole-2-methanol and 5-nitroindole did so in the monoclinic system. Six dimers corresponding to the most important interactions between the molecules in the crystal lattice were observed during the structural analysis. The interaction energy was calculated using CrystalExplorer program. The strongest interaction was the hydrogen bond of the N(1)–H···[O, N] type (dimer D5) forming a chain of interactions in the 4CYI, 5NI, and 5AI structures. In the structures of I2M and I3C, we can also see the chains of interactions. However, they are built by dimers D4 (OH···O). The N−H···π interaction type (dimer D1) are responsible for creating a characteristic “herringbone” motif in the structures of indole, 7-methylindole, 1H-indole-2-methanol, indol-3-carbinol, and 5-aminoindole. Indole and 7-methylindole are isostructural compounds. They have the same type of interactions described by dimers D1 (N−H···π), D2 (C−H···π), and D3 (π···π), an analogous layered structure. The crystalline structure composed of layers is also characteristic for the I2M, I3C, and 5NI structures. The other types of D6 dimers (dipole–dipole interaction) are characteristic of individual structures. Selected crystals were also subjected to morphological analysis. For indole-3-carbinol, 4-cyanoindole, 5-nitroinodel, and 5-aminoindole, theoretical crystal shapes are predicted using two models. They provide a good first approximation of the actual morphology, give information on what types of facets can be expected, and tell which direction of growth should be important. A few compounds, 4-cyanoindole, 5-nitroindole, and 5-aminoindole, were crystallized from various solvents to check the effect of the solvent type on the morphology of the crystals. The walls {002} and {011} are important for both 4-cyanoindole and 5-nitroindole crystals. A change in the morphological significance of a given facet family was observed along with an increase in the polarity of the solvent. In the case of 5-nitroindole for solvents with a higher dielectric constant, the walls {002} are more important, whereas the significance of the walls {001} drops. It can therefore be assumed that the molecules from the wall-cut layers {002} interact more strongly with the molecules of solvents with higher polarity. Looking at the layers built by individual families of walls, one can notice that the growth rate of a given plane depends on how strong the interactions are inside the layer. If the planes intersect the interactions in such a way that the strongest dimers are inside the layer, such planes will grow slowest, and thus their surfaces will be the largest. No patterns were observed for the 5-aminoindole crystals except that they crystallized only from polar solvents, and the obtained crystals had a flattened bulky shape.

Experimental Section

All indole derivatives and solvents used in crystallization experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

Crystallization

The following crystallization methods from the liquid phase were used: slow evaporation of the solvent and vapor diffusion. The latter method uses at least two solvents: one with high solubility of the solute and the other with less solubility (antisolvent). The vial with dissolved solute is placed in a dish with an antisolvent so that both vessels have a common gas phase. The solvents are selected, so the good solvent is more volatile than the antisolvent.

In the crystallization experiment, about 4–5 mg of the solid was placed in a 4 mL vial, then the solvent was added, and stirred on a magnetic stirrer until the substance was completely dissolved. After that, the sample was put away or placed in the 10 mL antisolvent vial. The experimental details are summarized in Supporting Information, Table S1.

X-ray Data Collection

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data collection for all compounds was performed at 100K Rigaku Eos SuperNova. Indexing and integration were performed with CrysAlisPro software (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction). Conventional spherical atom refinement was completed with SHELX2014,38 applying the full-matrix least-squares with the F2 method for all data sets. The X-ray experiment details can be found in Tables S2 and S3 (SI).

Computational Studies

The geometries of all of the crystal structures were optimized at the DFT(B3LYP)/6-31G** level of theory39−42 in CRYSTAL1743 before further computational analyses. During the optimization procedure, cell parameters were kept fixed, while the atom positions were varied. Crystal cohesive energies for the studied crystal systems were calculated at the same level of theory. The results were corrected for dispersion (DFT-D3)44−46 and the basis set superposition error (BSSE). Ghost atoms used for the BSSE estimation were selected up to 5 Å distance from the considered molecule in the crystal lattice. The evaluation of Coulombic and exchange series was controlled by five thresholds set to the values of 10–7, 10–7, 10–7, 10–7, and 10–25.

CrystalExplorer was used to evaluate interaction energies for all dimers present in the studied crystals. For indole and 7-methylindole, the energy for one orientation of molecules in the crystal lattice was calculated (orientation 1). As a result of the type of disorder in the structure of I2M, calculations for this structure were omitted. The total energy of a given dimer constitutes the sum of electrostatic, polarization, dispersion, and exchange-repulsion components. The molecular electron density was calculated at the DFT(B3LYP)/6-31G** level of theory using the above-described CRYSTAL-optimized molecular geometries. The dimer interaction energies were further used to generate the so-called energy frameworks (Figures S6–S10).47 Each dimer is connected with a line that had a width proportional to the strength of the interactions; the thicker the line, the stronger the interaction. The total energy is marked blue, while the electrostatic contribution is red, and the dispersion contribution is green.

Morphological Prediction

Before the morphological calculations, all crystal structures were optimized using the DFT (B3LYP)/6-31G** method in Crystal17 program.43 This is extremely important, especially due to the limited resolution of X-ray measurements and disorder in the structure.

The possible surfaces were selected using the BFDH method implemented in Mercury.48 For each of the identified morphologically important surfaces, the lattice energy was then partitioned with respect to its contribution to the growth process through the calculation of slice (Esl) and attachment (Eatt) energies (SI, Table S4). The attachment energies were assumed to be directly proportional to the relative face-specific growth rates. The attachment energies were scaled as center-to-face distances, and a Wulff plot was constructed using Vesta3.49 The morphology importance (MI) is defined as the ratio between the surface area of the facet to the total surface area of the crystal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Polish National Science Centre for financial support, Sonata grant UMO-2016/21/D/ST4/0374. The authors thank PLGrid Infrastructure (Prometheus, ACC Cyfronet) for providing the computer facilities where the GAUSSIAN16 and the CRYSTAL17 calculations were conducted.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01020.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Berger M.; Gray J. A.; Roth B. L. The Expanded Biology of Serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–366. 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordjman S.; Chokron S.; Delorme R.; Charrier A.; Bellissant E.; Jaafari N.; Fougerou C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 434–443. 10.2174/1570159X14666161228122115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-J.; Rahmani R. Preclinical and Clinical Pharmacology of Vinca Alkaloids. Drugs 1992, 44, 1–16. 10.2165/00003495-199200444-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven D. T. H.; Verhagen H.; Goldbohm R. A.; van den Brandt P. A.; van Poppel G. A review of mechanisms underlying anticarcinogenicity by brassica vegetables. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1997, 103, 79–129. 10.1016/S0009-2797(96)03745-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon J. V.; Delage B.; Williams D. E.; Dashwood R. H. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 224–236. 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M. C.; Crowley-Nowick P.; Bradlow H. L.; Sepkovic D. W.; Schmidt-Grimminger D.; Howell P.; Mayeaux E. J.; Tucker A.; Turbat-Herrera E. A.; Mathis J. M. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Indole-3-Carbinol in the Treatment of CIN. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 78, 123–129. 10.1006/gyno.2000.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravais A.Études Crystallographiques Part 1: Du cristal considere comme un simple assemblage de points; 1851. [Google Scholar]

- Friedel M. Etudes sur la loi de Bravais, Bulletin de la Societe Francaise. Mineralogique 1907, 30, 326. [Google Scholar]

- Donnay J.; Harker D. A new law of crystal morphology extending the law of Bravais. Am. Mineral. 1937, 22, 446. [Google Scholar]

- Frank F. C.Introductory Lecture, in Growth and Perfection of Crystals; Doremus B.; Turnbull D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Chernov A. The kinetics of the growth forms of crystals. Sov. Phys. Cryst. 1963, 7, 728. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman P.; Bennema P. The attachment energy as a habit controlling factor: I. Theoretical considerations. J. Cryst. Growth 1980, 49, 145. 10.1016/0022-0248(80)90075-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Feng S. Empirically augmented density functional theory for predicting lattice energies of aspirin, acetaminophen polymorphs, and ibuprofen homochiral and racemic crystals. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 2326. 10.1007/s11095-006-9006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes D. S.; Catlow C. R. A.; Gale J. D.; Rohl A. L.; Price S. L. Calculation of Attachment Energies and Relative Volume Growth Rates As an Aid to Polymorph Prediction. Cryst. Growth Des. 2005, 5, 879–885. 10.1021/cg049707d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovitch-Yellin Z.; Van Mil J.; Addadi L.; Idelson M.; Lahav M.; Leiserowitz L. Crystal morphology engineering by “tailor-made” inhibitors; a new probe to fine intermolecular interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 3111–3122. 10.1021/ja00297a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond R. B.; Orley M. J.; Roberts K. J.; Jackson R. A.; Quayle M. J. An Examination of the Influence of Divalent Cationic Dopants on the Bulk and Surface Properties of Ba(NO3)2 Associated with Crystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 2588–2594. 10.1021/cg8001674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poornachary S. K.; Chia V. D.; Yani Y.; Han G.; Chow P. S.; Tan R. B. H. Anisotropic Crystal Growth Inhibition by Polymeric Additives: Impact on Modulation of Naproxen Crystal Shape and Size. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 4844–4854. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staab E.; Addadi L.; Leiserowitz L.; Lahav M. Control of polymorphism by ‘tailor-made’ polymeric crystallization auxiliaries. Preferential precipitation of a metastable polar form for second harmonic generation. Adv. Mater. 1990, 2, 40–43. 10.1002/adma.19900020108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davey R. J.; Docherty R.; Blagden N.; Potts G. D. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals: Stabilization of a Metastable Form by Conformational Mimicry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 1767–1772. 10.1021/ja9626345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q.; Liu N.; Wang B.; Wang W. A study of solvent selectivity on the crystal morphology of FOX-7 via a modified attachment energy model. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 59784–59793. 10.1039/C6RA07129E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Liang Z.; Wu F.; Chen J.-F.; Xue C.; Zhao H. Crystal engineering of ibuprofen compounds: From molecule to crystal structure to morphology prediction by computational simulation and experimental study. J. Cryst. Growth 2017, 467, 47–53. 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2017.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N.; Zhou C.; Wu Z.; Lu X.; Wang B.; Wang W. Theoretical study on crystal morphologies of 1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitroethene in solvents: Modified attachment energy model and occupancy model. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2018, 85, 262–269. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T. H.; Rosbottom I.; Marziano I.; Hammond R. B.; Roberts K. J. Crystal Morphology and Interfacial Stability of RS-Ibuprofen in Relation to Its Molecular and Synthonic Structure. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 3088–3099. 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b01878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E.; Delgado Nunes V.; Buckner S.; Latchem S.; Constanti M.; Miller P.; Doherty M.; Zhang W. Y.; Birrell F.; Porcheret M. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 552. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosbottom I.; Ma C. Y.; Turner T. D.; O’Connell R. A.; Loughrey J.; Sadiq G.; Davey R. J.; Roberts K. J. Influence of Solvent Composition on the Crystal Morphology and Structure of p-Aminobenzoic Acid Crystallized from Mixed Ethanol and Nitromethane Solutions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 4151–4161. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan A. A.; Rosbottom I.; Ramachandran V.; Pask C. M.; Olomukhoro O.; Roberts K. J. Crystallographic Structure, Intermolecular Packing Energetics, Crystal Morphology and Surface byChemistry of Salmeterol Xinafoate (Form I). J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 882–891. 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panina N.; Van de Ven R.; Janssen F.; Meekes H.; Vlieg E.; Deroover G. Study of the needle-like morphologies of two Beta-Phthalocyanines. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 840. 10.1021/cg800437y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Trout B. L. Computer-Aided Solvent Selection for Improving the Morphology of Needle-like Crystals: A Case Study of 2,6-Dihydroxybenzoic Acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 4379. 10.1021/cg1004903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovette M. A.; Doherty M. F. Needle-shaped crystals: Causality and solvent selection guidance based on periodic bond chains. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 3341. 10.1021/cg301830u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belenguer A. M.; Lampronti G. I.; Cruz-Cabeza A. J.; Hunter C. A.; Sanders J. K. M. Solvation and surface effects on polymorph stabilities at the nanoscale. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 6617–6627. 10.1039/C6SC03457H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinska M.; Kieliszek A.; Kozioł A. E.; Mirosław B.; Woźniak K. Interplay between packing, dimer interaction energy and morphology in a series of tricyclic imide crystals. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2020, 76, 157–165. 10.1107/S2052520620001304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch A.; Verma V.; Zeglinski J.; Bannigan P.; Rasmuson A. Face indexing and shape analysis of salicylamide crystals grown in different solvents. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 2648–2659. 10.1039/C9CE00049F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W.; Chu Y.; Xia M.; Lei W.; Wang F. Crystal morphology prediction of 1,3,3-trinitroazetidine in ethanol solvent by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2016, 64, 94–100. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L.; Chen L.; Wang J.; Chen F.; Lan G. Prediction of crystal morphology of 3,4-Dinitro-1H-pyrazole (DNP) in different solvents. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2017, 75, 62–70. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D.; Zhang S.; Cui P.; Wang C.; Dai J.; Zhou L.; Huang Y.; Hou B.; Hao H.; Zhou L.; Yin Q. Solvent Effects on Catechol Crystal Habits and Aspect Ratios: A Combination of Experiments and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Crystals 2020, 10, 316. 10.3390/cryst10040316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roychowdhury P.; Basak B. S. The crystal structure of indole. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1975, 31, 1559–1563. 10.1107/S0567740875005687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. J.; Wolff S.; Grimwood D. J.; Spackman P. R.; Jayatilaka D.; Spackman M. A.. CrystalExplorer17; University of Western Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R.; Binkley J. S.; Seeger R.; Pople J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovesi R.; Erba A.; Orlando R.; Zicovich-Wilson C. M.; Civalleri B.; Maschio L.; Rérat M.; Casassa S.; Baima J.; Salustro S.; Kirtman B. Quantum-mechanical condensed matter simulations with CRYSTAL. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1360 10.1002/wcms.1360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg J. G.; Grimme S.. Prediction and Calculation of Crystal Structures: Methods and Applications; Atahan-Evrenk S.; Aspuru-Guzik A., Eds.; Topics in Current Chemistry; Springer, 2014; pp 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. J.; Thomas S. P.; Shi M. W.; Jayatilaka D.; Spackman M. A. Energy frameworks: insights into interaction anisotropy and the mechanical properties of molecular crystals. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3735–3738. 10.1039/C4CC09074H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. F.; Bruno I. J.; Chisholm J. A.; Edgington P. R.; McCabe P.; Pidcock E.; Rodriguez-Monge L.; Taylor R.; Streek J. V. D.; Wood P. A. Mercury CSD 2.0 - new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. 10.1107/S0021889807067908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Momma K.; Izumi F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. 10.1107/S0021889811038970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.