Abstract

Background

To assess participation of children with visual impairment, the Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth (PAI-CY) was recently developed. This study assessed some initial psychometric properties of the PAI-CY 13–17 years version, and investigated its feasibility.

Methods

Adolescents with visual impairment and their parents (n = 72 dyads) completed the self-report and proxy-report version of the 58-item PAI-CY, an evaluation form and several questionnaires measuring related constructs. Item deletion was informed by item responses, inter-item correlations, test-retest reliability, adolescent-parent agreement and participants’ feedback. Known-group validity and concurrent validity with related questionnaires were investigated for the final item-set.

Results

Twelve items had > 20% missing values, whereas 39 items showed floor effects. Eight item pairs showed high inter-item correlations. Test-retest reliability was acceptable for most items (kappa ≥0.4). Evaluation forms showed that over 90% of respondents was neutral to very positive regarding several feasibility aspects such as administration time and comprehensiveness. Adolescent-parent agreement was mostly low. These results informed the deletion of three items. Known-group validity seemed adequate since PAI-CY scores were significantly worse for participants with comorbidity compared to those without. A trend towards worse scores for participants with more severe visual impairment was also observed. Correlations between the PAI-CY and related questionnaires confirmed concurrent validity.

Conclusions

Initial psychometric properties of the PAI-CY 13–17 were acceptable, although more work is needed to assess other psychometric properties, such as the underlying construct. Following implementation in low vision care to assess participation needs, enabling larger samples, acceptability of the PAI-CY 13–17 to end-users should be carefully monitored, especially if alterations are made based on the current study.

Keywords: Visual impairment, Questionnaire, Participation, Psychometric properties, Adolescents

Background

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) evaluate outcomes of health, illness or treatment that are important to patients and directly reported by patients themselves. They include for example symptom severity, health perception, and quality of life [1]. PROMs are increasingly used for evaluating health services, establishing treatment effectiveness, and informing clinical decision-making. PROMs can contribute to clinician-patient communication, facilitate the process of shared decision-making and improve patient satisfaction with care [2–4].

Numerous PROMs currently exist, and a fair share are developed specifically for children. These include generic instruments (e.g. [5–7]) facilitating comparison of different patient populations, as well as disease-specific instruments specifically targeted to those with the condition of interest. Until recently there was a paucity in the development of PROMs to capture the perspectives of children and adolescents with visual impairment (VI), possibly relating to the challenges to develop PROMs for this population. For instance, psychometric validation of PROMs depends on large and representative samples, but the population of children with VI is numerically small, complex, heterogeneous and difficult to reach. Despite the challenges, various instruments for children and adolescents with VI have been developed in recent years, mainly focusing on vision-related quality of life and functional vision (e.g. [8–12]).

We recently developed the Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth (PAI-CY), which focuses on participation of children with VI. Four age-appropriate versions of the PAI-CY were developed reflecting the developmental age-bands of the World Health Organization (WHO): 0–2 years (proxy-report), 3–6 years (proxy-report), 7–12 years (proxy and self-report) and 13–17 years (proxy and self-report). Additionally, the PAI Young Adults (PAI-YA) was developed aimed at persons aged 18–25 years. The PAI-CY was developed to structure the process of identifying needs from the perspectives of children with VI and their parents at Dutch low vision services. Its content was shaped involving end-users as stakeholders in a concept-mapping study [13], ensuring face and content validity, and a small-scale pilot-study demonstrated its feasibility and acceptability [14].

This study reports the first stage psychometric evaluation of the PAI-CY 13–17. This includes the assessment of some important psychometric properties, such as test-retest reliability, known-group validity and concurrent validity with other instruments. These analyses were intended to capture the worst performing items, resulting in initial item reduction. Moreover, some feasibility aspects were assessed.

Methods

Subjects and procedures

Adolescents aged 13–17 years registered at two Dutch low vision services and their parents/caretakers (parents for brevity) were invited to participate. Participants had to have adequate knowledge and understanding of the Dutch language. Children with major cognitive impairment were excluded from invitation by the low vision rehabilitation centers. Prior to participation in the study, written informed consent was obtained from adolescents and their parents. Adolescents completed the questionnaires through a face-to-face interview in their own homes, whereas parents completed the questionnaires through a web-based survey. For adolescents, the questionnaires consisted of the PAI-CY 13–17, a self-constructed evaluation form to further assess some feasibility aspects, and the Dutch versions of the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP) [7], Kidscreen-27 [5], and the Functional Vision Questionnaire for Children and Young People (FVQ_CYP_NL) [8, 15]. Parents completed the proxy versions of the PAI-CY 13–17 and evaluation form, CASP and Kidscreen. Parents also completed questions regarding sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of their child. Approximately 2 weeks after initial completion [16], participants were asked to complete a retest. Adolescents were interviewed by the same interviewer. Ophthalmic information of adolescents was retrieved from the patient files at the low vision services organizations; missing values were complemented with self-reported data from parents (n = 8). Visual acuity was classified using five levels based on the better seeing eye, according the criteria of the WHO [17].

The PAI-CY 13–17

The preliminary version of the PAI-CY 13–17 contained 58 items grouped into eight domains (for descriptive purposes only, in order to provide contextual meaning) that were informed by concept-mapping workshops with end-users (see Table 2) [13]. Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with response options not difficult (1), slightly difficult (2), very difficult (3), and impossible (4). The response option not applicable was handled as a missing value. The items in the proxy version only differed in first or third person tense.

Table 2.

Distribution of responses and parameters of test-retest reliability and adolescent-parent agreement

| Domain1 and item content | Missing (%) | Distribution of responses over response categories2 (%) | Test-retest reliability parameters | Adolescent-parent agreement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Agreement (%) | Weighted kappa | Agreement (%) | Weighted kappa | |||

| LT1: Doing sports | Adolescent | 13.0 | 62.7 | 37.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 74.6 | 0.53 | 66.1 | 0.38 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 38.0 | 52.1 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 64.1 | 0.62 | |||

| LT2: Keeping up with others during play/sports | Adolescent | 3.9 | 68.9 | 27.0 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.47 | 42.0 | 0.19 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 28.2 | 47.9 | 16.9 | 7.0 | 64.1 | 0.72 | |||

| LT3: Using social media | Adolescent | 3.9 | 90.5 | 8.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 85.7 | 0.09 | 79.4 | 0.34 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 76.1 | 21.1 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 87.1 | 0.61 | |||

| LT4: Playing games on computer, tablet, phone | Adolescent | 15.6 | 83.1 | 16.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 80.6 | 0.22 | 74.2 | 0.23 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 70.4 | 26.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 81.3 | 0.70 | |||

| LT5: Watching films/television | Adolescent | 1.3 | 64.5 | 32.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 77.5 | 0.57 | 57.7 | 0.17 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 48.6 | 44.4 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 75.4 | 0.65 | |||

| LT6: Going to a club independentlyb,c | Adolescent | 46.8 | 90.2 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 83.9 | 0.69 | 68.3 | 0.57 |

| Parent | 13.0 | 44.8 | 19.4 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 66.7 | 0.87 | |||

| LT7: Participating at a club | Adolescent | 27.3 | 91.1 | 8.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 91.5 | −0.03 | 54.0 | 0.13 |

| Parent | 14.3 | 51.5 | 28.8 | 19.7 | 0.0 | 65.5 | 0.70 | |||

| LT8: Making music | Adolescent | 51.9 | 70.3 | 27.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 0.49 | 61.8 | 0.36 |

| Parent | 29.9 | 59.3 | 33.3 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 85.0 | 0.84 | |||

| LT9: Performing a hobby | Adolescent | 33.8 | 76.5 | 21.6 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 79.5 | 0.43 | 64.5 | 0.18 |

| Parent | 46.8 | 61.0 | 31.7 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 85.7 | 0.83 | |||

| MO1: Cyclingd,e | Adolescent | 9.1 | 54.0 | 27.1 | 7.1 | 11.4 | 75.8 | 0.78 | 69.2 | 0.74 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 46.5 | 26.8 | 9.9 | 16.9 | 81.3 | 0.90 | |||

| MO2: Cycling to something independentlyb,d,f | Adolescent | 13.0 | 70.1 | 13.4 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 79.0 | 0.90 | 75.4 | 0.70 |

| Parent | 9.1 | 51.4 | 15.7 | 7.1 | 25.7 | 79.0 | 0.90 | |||

| MO3: Going to a friend in the neighborhoodc,e,f | Adolescent | 13.0 | 80.6 | 11.9 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 90.3 | 0.87 | 71.0 | 0.57 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 54.9 | 21.1 | 15.5 | 8.5 | 74.6 | 0.83 | |||

| MO4: Participating in traffic independently | Adolescent | 6.5 | 63.9 | 26.4 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 75.0 | 0.64 | 44.8 | 0.40 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 34.7 | 38.9 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 72.3 | 0.85 | |||

| MO5: Estimating speeds | Adolescent | 2.6 | 37.3 | 40.0 | 21.3 | 1.3 | 69.0 | 0.70 | 47.1 | 0.30 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 15.5 | 45.1 | 29.6 | 9.9 | 75.0 | 0.70 | |||

| MO6: Using public transport independently | Adolescent | 31.2 | 69.8 | 15.1 | 11.3 | 3.8 | 81.6 | 0.61 | 50.0 | 0.53 |

| Parent | 19.5 | 33.9 | 37.1 | 17.7 | 11.3 | 63.3 | 0.82 | |||

| MO7: Learning new routes | Adolescent | 3.9 | 68.9 | 24.3 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 68.1 | 0.34 | 47.1 | 0.12 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 46.5 | 32.4 | 19.7 | 1.4 | 78.1 | 0.83 | |||

| SC1: Making contact with others | Adolescent | 0.0 | 83.1 | 13.0 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 86.3 | 0.46 | 66.7 | 0.35 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 61.1 | 30.6 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 72.3 | 0.64 | |||

| SC2: Doing activities with peers without VIg | Adolescent | 3.9 | 71.6 | 21.6 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 80.9 | 0.70 | 64.7 | 0.37 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 54.9 | 29.6 | 15.5 | 0.0 | 74.2 | 0.68 | |||

| SC3: Participating in group activities | Adolescent | 0.0 | 67.5 | 22.1 | 9.1 | 1.3 | 80.3 | 0.55 | 44.9 | 0.16 |

| Parent | 10.4 | 34.8 | 39.1 | 23.2 | 2.9 | 64.4 | 0.71 | |||

| SC4: Shopping with friendsa | Adolescent | 44.2 | 93.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 87.9 | −0.05 | 73.0 | 0.46 |

| Parent | 18.2 | 58.7 | 22.2 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 76.4 | 0.85 | |||

| SC5: Going a night out with friends | Adolescent | 50.6 | 60.5 | 28.9 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 86.2 | 0.76 | 66.7 | 0.52 |

| Parent | 28.6 | 36.4 | 34.5 | 18.2 | 10.9 | 69.0 | 0.84 | |||

| SC6: Datingg | Adolescent | 74.0 | 90.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 100.0 | n/a | 78.6 | 0.00 |

| Parent | 51.9 | 51.4 | 27.0 | 21.6 | 0.0 | 74.1 | 0.80 | |||

| SC7: Dealing with amorousness | Adolescent | 58.4 | 96.9 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | n/a | 83.3 | 0.00 |

| Parent | 44.2 | 69.8 | 18.6 | 11.6 | 0.0 | 83.3 | 0.58 | |||

| CO1: Being able to express in words properly | Adolescent | 0.0 | 80.5 | 16.9 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 87.7 | 0.69 | 84.7 | 0.61 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 83.3 | 15.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 80.0 | 0.51 | |||

| CO2: Asking questions | Adolescent | 2.6 | 80.0 | 16.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 77.8 | 0.37 | 70.4 | 0.34 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 65.3 | 30.6 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 73.8 | 0.57 | |||

| CO3: Talking about feelings | Adolescent | 14.3 | 60.6 | 28.8 | 10.6 | 0.0 | 67.7 | 0.45 | 47.6 | 0.25 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 44.4 | 38.9 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 64.6 | 0.64 | |||

| CO4: Participating in a conversation actively | Adolescent | 1.3 | 90.8 | 7.9 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 90.3 | 0.54 | 76.1 | 0.14 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 79.2 | 18.1 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 84.6 | 0.62 | |||

| CO5: Asking help from familiar people | Adolescent | 2.6 | 82.7 | 17.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 85.9 | 0.47 | 64.8 | 0.15 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 68.1 | 25.0 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 70.8 | 0.37 | |||

| CO6: Asking help from unfamiliar people | Adolescent | 7.8 | 52.1 | 35.2 | 11.3 | 1.4 | 73.1 | 0.46 | 47.8 | 0.25 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 39.4 | 38.0 | 21.1 | 1.4 | 72.6 | 0.68 | |||

| CO7: Estimating emotions of others | Adolescent | 1.3 | 56.6 | 34.2 | 7.9 | 1.3 | 74.0 | 0.70 | 63.8 | 0.37 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 47.2 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 2.8 | 64.6 | 0.66 | |||

| CO8: Estimating the distance to others | Adolescent | 2.6 | 73.3 | 18.7 | 6.7 | 1.3 | 70.0 | 0.58 | 52.9 | 0.09 |

| Parent | 9.1 | 52.9 | 40.0 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.55 | |||

| CO9: Stating that you want to join in a group | Adolescent | 5.2 | 78.1 | 19.2 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 91.0 | 0.73 | 55.9 | 0.36 |

| Parent | 9.1 | 48.6 | 41.4 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 63.5 | 0.56 | |||

| CO10: Giving your opinion | Adolescent | 1.3 | 85.5 | 9.2 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 87.5 | 0.60 | 73.2 | 0.09 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 77.8 | 19.4 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 76.9 | 0.45 | |||

| CO11: Dealing with bullying | Adolescent | 51.9 | 48.6 | 27.0 | 21.6 | 2.7 | 52.4 | 0.60 | 48.3 | 0.41 |

| Parent | 28.6 | 34.5 | 43.6 | 21.8 | 0.0 | 59.1 | 0.62 | |||

| SL1: Finding the way in school | Adolescent | 0.0 | 90.9 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 94.4 | 0.65 | 76.4 | 0.20 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 80.6 | 18.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 85.9 | 0.57 | |||

| SL2: Keeping overview in class | Adolescent | 1.3 | 81.6 | 14.5 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 87.1 | 0.66 | 50.7 | 0.25 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 48.6 | 45.8 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 78.5 | 0.68 | |||

| SL3: Keeping up with classmates | Adolescent | 1.3 | 73.7 | 21.1 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 86.1 | 0.66 | 62.8 | 0.26 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 49.3 | 35.2 | 15.5 | 0.0 | 65.1 | 0.64 | |||

| SL4: Cooperating with others | Adolescent | 1.3 | 77.6 | 15.8 | 6.6 | 0.0 | 88.4 | 0.83 | 67.6 | 0.37 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 63.9 | 30.6 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 0.68 | |||

| SL5: Reading the slide board or schoolboard | Adolescent | 6.5 | 50.0 | 26.4 | 15.3 | 8.3 | 65.7 | 0.67 | 41.5 | 0.32 |

| Parent | 10.4 | 18.8 | 52.2 | 15.9 | 13.0 | 59.6 | 0.65 | |||

| SL6: Making homework independently | Adolescent | 7.8 | 77.5 | 18.3 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 89.2 | 0.79 | 68.2 | 0.34 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 63.9 | 30.6 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 76.6 | 0.71 | |||

| SL7: Finding information | Adolescent | 2.6 | 74.7 | 20 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 82.1 | 0.44 | 65.2 | 0.14 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 63.4 | 35.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.44 | |||

| SL8: Maintaining energy levels for fun activities | Adolescent | 1.3 | 48.7 | 38.2 | 11.8 | 1.3 | 74.6 | 0.65 | 63.4 | 0.57 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 37.5 | 38.9 | 23.6 | 0.0 | 70.8 | 0.75 | |||

| SL9: Choosing appropriate further education | Adolescent | 54.5 | 71.4 | 11.4 | 14.3 | 2.9 | 73.1 | 0.83 | 54.8 | 0.35 |

| Parent | 27.3 | 39.3 | 25.0 | 33.9 | 1.8 | 65.9 | 0.73 | |||

| SR1: Cooking independently | Adolescent | 32.5 | 78.8 | 13.5 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 79.1 | 0.47 | 55.6 | 0.23 |

| Parent | 24.7 | 48.3 | 29.3 | 19.0 | 3.4 | 87.5 | 0.92 | |||

| SR2: Doing the dishes | Adolescent | 16.9 | 90.6 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 93.1 | 0.58 | 67.2 | 0.23 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 64.8 | 29.6 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 83.1 | 0.75 | |||

| SR3: Operating devices at home | Adolescent | 1.3 | 89.5 | 10.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 90.3 | 0.19 | 75.7 | 0.10 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 73.2 | 21.1 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 79.7 | 0.67 | |||

| SR4: Shopping for groceries | Adolescent | 15.6 | 76.9 | 10.8 | 7.7 | 4.6 | 79.7 | 0.63 | 69.8 | 0.62 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 59.2 | 26.8 | 4.2 | 9.9 | 81.0 | 0.89 | |||

| SR5: Picking clothes independently | Adolescent | 15.6 | 84.6 | 10.8 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 89.5 | 0.49 | 70.7 | 0.38 |

| Parent | 9.1 | 60.0 | 30.0 | 8.6 | 1.4 | 77.4 | 0.78 | |||

| SR6: Brushing your teeth independently | Adolescent | 1.3 | 96.1 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 94.4 | 0.44 | 88.5 | 0.09 |

| Parent | 9.1 | 88.6 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 90.5 | 0.74 | |||

| SR7: Going to the toileth | Adolescent | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | n/a | 94.4 | 0.00 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 94.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 93.8 | 0.58 | |||

| SR8: Bathing/showering independentlyh | Adolescent | 0.0 | 97.4 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1.00 | 95.8 | 0.38 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 93.1 | 5.6 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 93.8 | 0.65 | |||

| SR9: Doing your hair | Adolescent | 14.3 | 83.3 | 15.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 89.8 | 0.45 | 79.0 | 0.38 |

| Parent | 7.8 | 77.5 | 19.7 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 81.0 | 0.61 | |||

| SR10: Dealing with the menstruation (girl) | Adolescent | 11.1 | 91.7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 95.8 | 0.88 | 83.3 | 0.67 |

| Parent | 11.1 | 75.0 | 20.8 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 88.9 | 0.74 | |||

| AC1: Telling about your VI | Adolescent | 2.6 | 68.0 | 24.0 | 6.7 | 1.3 | 77.5 | 0.64 | 62.8 | 0.31 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 56.9 | 27.8 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 70.8 | 0.63 | |||

| AC2: Empathizing with others | Adolescent | 1.3 | 80.3 | 15.8 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 80.6 | 0.44 | 57.7 | 0.20 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 58.3 | 30.6 | 9.7 | 1.4 | 60.0 | 0.59 | |||

| AC3: Dealing with incapability | Adolescent | 3.9 | 44.6 | 36.5 | 17.6 | 1.4 | 51.4 | 0.49 | 40.6 | 0.14 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 30.6 | 55.6 | 13.9 | 0.0 | 61.5 | 0.43 | |||

| AC4: Dealing with making mistakes | Adolescent | 3.9 | 56.8 | 24.3 | 17.6 | 1.4 | 78.9 | 0.78 | 55.7 | 0.38 |

| Parent | 6.5 | 37.5 | 41.7 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 70.8 | 0.70 | |||

| FI1: Paying independentlya | Adolescent | 5.2 | 90.4 | 8.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 98.5 | 0.93 | 73.8 | 0.32 |

| Parent | 13.0 | 70.1 | 19.4 | 7.5 | 3.0 | 81.7 | 0.85 | |||

VI visual impairment

1 LT: leisure time; MO: mobility; SC: social contacts; CO: communication; SL: school; SR: self-reliance; AC: acceptance/self-consciousness; FI: finances

2 1: not difficult; 2: slightly difficult; 3: very difficult; 4: impossible

a item pair with inter-item correlation > 0.8 in the adolescent version

b,c,d,e,f,g,h item pairs with inter-item correlation > 0.8 in the parent version

Statistical analyses

As a first step in the psychometric evaluation of the PAI-CY 13–17, item reduction was performed conservatively, using lenient criteria. Items were considered for elimination if the psychometric performance was suboptimal on several criteria and if item content was already adequately represented in other items: a) Items with missing scores > 20% [8, 16] in both the adolescent and parent version and/or items with > 70% [8, 18, 19] of both adolescents and parents endorsing the first or last response category (i.e. floor or ceiling effects). b) Items showing inter-item correlations > 0.8, indicating potential redundancy. c) Suboptimal values of test-retest reliability [16] using weighted kappa and percentage agreement [20, 21]. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for sum scores of the test and retest data were calculated based on absolute agreement, with a two-way mixed-effects model.

Subsequently, adolescent-parent agreement at item level was investigated using weighted kappa and percentage agreement. The ICC for the sum scores of the adolescent and parent data were calculated based on absolute agreement, with a two-way random-effects model. Comments and suggestions evolving from the evaluation forms were used to inform decisions on item elimination or instrument adaptation.

Known-group validity on the final item-set [16] was investigated using independent samples t-tests (median split for age) and ANOVAs with a post-hoc Tukey test. Lastly, concurrent validity [16] with subscales of the Kidscreen, CASP and FVQ_CYP_NL was investigated with Spearman’s correlations. Negative correlations were expected between the PAI-CY and subscales of the Kidscreen and CASP, whereas positive correlations were expected with the FVQ_CYP_NL. Correlations were expected to be smallest between the PAI-CY and the Kidscreen and largest for the FVQ_CYP_NL.

Results

Of an estimated 700 invited adolescents and their parents, 77 provided written informed consent and completed the first questionnaire (either the adolescent or parent version). Main reasons for non-participation were no time, not interested or adolescents not willing to participate. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Complete data was obtained from 72 adolescent-parent dyads. The retest was completed by 64 parents after 28.3 ± 24.3 (range 9–121, median 18) days and 74 adolescents after 15.9 ± 7.0 (range 7–44, median 14) days.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

| Variable | All participants |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (range) | 14.66 ± 1.49 (13–17) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 49 (63.6) |

| Severity of VI, n (%) | |

| No VI: logMAR ≤0.3 | 25 (32.5) |

| Mild VI: logMAR 0.31–0.52 | 13 (16.9) |

| Moderate VI: logMAR 0.53–1.00 | 22 (28.6) |

| Severe VI: logMAR 1.01–1.30 | 3 (3.9) |

| Blind: logMAR ≥1.31 or visual field ≤10 degrees | 11 (14.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (3.9) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 31 (42.5) |

| Parent who completed the questionnaire, n (%) | |

| Mother | 49 (67.1) |

| Father | 13 (17.8) |

| Mother and father together | 8 (11.0) |

| Caretaker | 3 (4.1) |

| Dutch nationality parent, n (%) | 70 (95.9) |

| Education in years parent, mean ± SD (range) | 11.53 ± 4.10 (0–16) |

| Financial situation parent, n (%) | |

| Usually enough money | 38 (52.1) |

| Just enough money | 15 (20.5) |

| Not enough money | 8 (11.0) |

| No answer | 12 (16.4) |

SD standard deviation, VI visual impairment

Twelve items had missing responses > 20% in either the adolescent or parent version, of which eight items had > 20% missing scores in both versions (Table 2). Floor effects were found in 39 items in either the adolescent or parent version, of which 13 items displayed floor effects in both versions. Inter-item correlations of > 0.8 were found in one item pair for adolescents and seven item pairs for parents. Most items showed satisfactory test-retest reliability. For three items agreement was < 60%, whereas for eight items weighted kappa was < 0.4. ICC for the sum score on test and retest for adolescents was 0.866 (95%-confidence interval: 0.791–0.915). For parents, the ICC was 0.882 (95%-confidence interval: 0.815–0.927). With respect to adolescent-parent agreement, 34% of the items showed agreement < 60%, while 79% of the items showed weighted kappa’s ≤ 0.4. ICC between adolescent and parent scores was 0.438 (95%-confidence interval: 0.000–0.694).

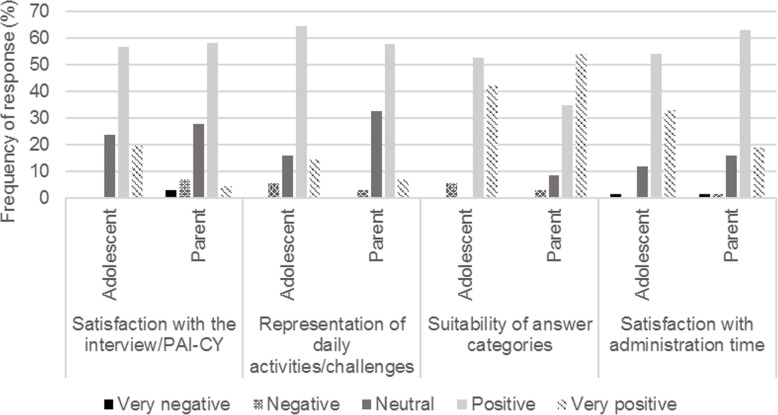

The evaluation forms showed that parents’ self-reported administration time (including questions about sociodemographic and clinical characteristics) was 22 ± 14 (range 8–60, median 17) minutes. Over 90% of both adolescents and parents were neutral to very positive regarding various feasibility aspects of the PAI-CY (Fig. 1). However, comments and suggestions for improvements were made by 42 adolescents and/or parents (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of the PAI-CY 13–17 by adolescents and parents

Table 3.

Comments of > 1 respondents relevant to the PAI-CY 13–17 and suggested solutions

| Comments | Suggested solutions |

|---|---|

| “Questions about make-up and personal care are missing” | Adding item: SR: paying attention to your facial care |

| “The textbox to give additional information should be larger” | Enlarging the textbox |

| “A question regarding which form of guidance is warranted is lacking” | No adjustment – this can be filled in as response to the question clarifying needs following each domain |

| “I would like to have a textbox to give additional information at the end of the questionnaire” | Adding textbox at the end of the questionnaire |

| “I miss questions about how siblings or the social environment deal with the disability” | Adding items: PE: difficulty of siblings regarding the visual impairment; PE: difficulty of other friends/family regarding the visual impairment |

| “A question regarding the needs of the parents/adolescents” | No adjustment – this can be filled in as response to the question clarifying needs following each domain |

| “Questions about self-reliance and personal care are too easy/not age-appropriate” | No adjustment – larger samples are needed prior to deletion of these items |

| “Questions about side jobs are missing” | Adding items: LT: finding and applying for a side job; LT: properly performing your side job |

| “A response option between slightly difficult and very difficult is lacking” | Adding the response option ‘difficult’ |

| “I would like to have more questions regarding energy balance and fatigue” | Adding items: AC: dividing your energy over the day; AC: doing your daily activities without getting fatigued |

| “I miss questions about getting a driver license for a car or scooter” | Adding items: MO: finding information about the possibilities to get your driver’s license for car or scooter |

| “Questions regarding recognizing other people are missing” | Adding item: CO: recognizing other people |

| “I miss questions about school stuff outside the classroom, for example about school trips” | Adding item: SL: participating in school activities outside the regular classes |

| “Questions about walking in a crowded unknown environment, for example in shops, are lacking” | No adjustment – covered by item regarding shopping |

| “Questions about the difficulty of darkness or too much light are missing” | Adding item: MO: participating in traffic at night |

SR self-reliance, PE parental experiences, LT leisure time, AC acceptance/self-consciousness, MO mobility, CO communication, SL school

From these results, it was decided to eliminate items LT8, MO2, and CO4, resulting in a PAI-CY 13–17 containing 55 items. Infrequent endorsement of the answer category ‘impossible’ motivated collapsing this category with the category ‘very difficult’. Table 4 shows expected patterns of correlations between the PAI-CY and concurrent questionnaires.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients of the PAI-CY 13–17 with the CASP, Kidscreen and FVQ_CYP_NL

| Subscale | Adolescents | Parents |

|---|---|---|

| CASP total | − 0.71* | − 0.87* |

| CASP home | − 0.49* | − 0.80* |

| CASP community | − 0.60* | − 0.83* |

| CASP school | − 0.41* | − 0.71* |

| CASP living | − 0.58* | − 0.83* |

| Kidscreen physical | − 0.39* | − 0.58* |

| Kidscreen psychological | − 0.41* | − 0.47* |

| Kidscreen parent | − 0.28 | − 0.46* |

| Kidscreen peers | − 0.15 | − 0.44* |

| Kidscreen school | −0.26 | − 0.29 |

| FVQ_CYP_NL | 0.68* | n/a |

n/a not applicable, CASP Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation, FVQ_CYP_NL Dutch version of the Functional Vision Questionnaire for Children and Young People

* Significant correlation (p < 0.01)

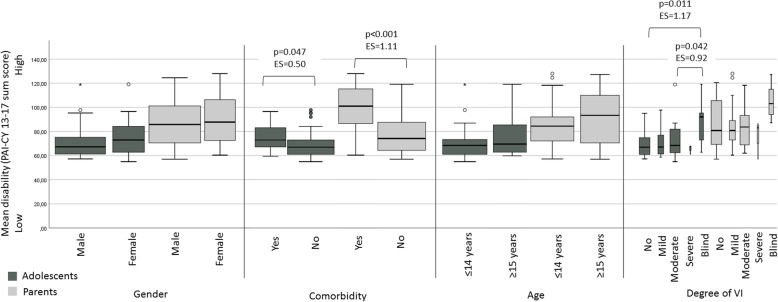

Adolescents with comorbidity scored significantly worse on the PAI-CY 13–17 than adolescents without comorbidity, both in the adolescent and parent version (effect sizes were moderate to large). In the adolescent version, significantly worse scores were found for adolescents with blindness compared to those with moderate VI and no VI (large effect sizes). All other effect sizes were small (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Boxplots for groups that differ on gender, comorbidity, age and degree of VI. Box width represents group sizes. ES: effect size; VI: visual impairment

Discussion

In this study the psychometric properties of the PAI-CY 13–17 were evaluated, a questionnaire to assess the needs of Dutch adolescents with VI and their parents. We used less stringent criteria for item elimination because of the importance of face and content validity and the small sample size. Therefore, we only eliminated three items, of which content was thought to be adequately represented in the remaining items (LT8: making music can be captured with LT9: performing a hobby, MO2: cycling to something independently with MO1: cycling and CO4: participating in a conversation actively with CO1: Being able to express in words properly). Eliminating more items while having a small sample size could be counterproductive in the long term, causing potentially informative items to be discarded before larger samples are available. Once the PAI-CY 13–17 is used in future, confirmation of the findings and the assessment of other psychometric properties should inform further item reduction, although the current number of items is in line with other age-versions of the PAI-CY and PAI-YA, containing 27–60 items [22–25]. Moreover, with larger samples item response theory modeling might be employed to make the instrument more precise and user-friendly.

Test-retest reliability was satisfactory for most items. Exclusion of participants who completed the retest > 45 days after the first questionnaire (n = 10) in general had a positive influence on kappa, agreement and the ICC (data not shown). Remarkably, the items with suboptimal kappa values showed adequate agreement. This phenomenon has previously been reported as the ‘paradox’ of the kappa statistic, in which low values of kappa can be found for high values of agreement [26, 27], caused by symmetrically imbalanced contingency tables [28]. For example, for item LT7: participating at a club, many adolescents opted “not difficult” on the test and retest, resulting in a high proportion of adolescents (0.98) in row 1 in the contingency table. As the proportion of respondents in row 1 increases, kappa decreases rapidly and may even fall below zero, as has happened for this item, despite excellent agreement. Therefore, agreement and weighted kappa should be re-examined with larger samples. The ICC between the sum scores of the test and retest data were high for both adolescents and parents, indicating good reliability. Adolescent-parent agreement and weighted kappa was low for many items, as was the ICC between the sum scores, indicating that adolescents and their parents have different perceptions about the difficulties adolescents experience. In general, adolescents perceive items as less difficult than parents. Notably, agreement was highest for those items taking place at home, i.e. items in the self-reliance domain. This might indicate that for activities taking place elsewhere, parents might be less aware about the difficulties experienced by their child, and therefore overestimate the difficulties experienced by adolescents. However, due to their age, adolescents also might overestimate their abilities and perceive less risks. Therefore, retrieving information from both sources is important to comprehensively assess adolescents’ needs.

It was possible to differentiate between adolescents with or without comorbidity, both with the adolescent and parent version. Furthermore, it was possible to differentiate between different degrees of VI with the adolescent version, while there was a trend with the parent version. The correlations with other instruments demonstrated concurrent validity of the PAI-CY 13–17. The relatively low correlation with subscales of the Kidscreen demonstrates that the PAI-CY 13–17 is not necessarily measuring quality of life, whereas the strong correlations with (subscales) of the CASP and the FVQ_CYP_NL confirms that the PAI-CY 13–17 rather measures a construct related to participation or functional vision. Although one can argue that the PAI-CY and FVQ_CYP_NL might be similar, the relatively strong but not perfect correlation shows that both instruments measure a similar construct, but each in its unique way.

One of the major limitations of the current study is the small sample size and the low response rate, although anticipated from previous studies involving similar populations. Main reasons for non-participation according to parents were no time, not interested or their child stating they did not want to participate. Adolescents might be reluctant to participate in scientific research, especially if they have to make an appointment and are visited by a researcher in their own homes.

The small sample size prevented factor analysis and the use of item response theory to optimize the PAI-CY 13–17. However, previous studies examining other age-versions of the PAI-CY and the PAI-YA showed the items comprised a unidimensional scale [22–24]. As such, the PAI-CY 13–17 is expected to be unidimensional as well, and we calculated sum scores for the complete scale.

The current study used a national sample, implying that the PAI-CY 13–17 should be applicable across the Dutch population. Although the PAI-CY 13–17 can be used as a template for use in other countries, cross-cultural validation is recommended for use outside the Netherlands. Recent interest to use various age-versions of the PAI-CY and the PAI-YA in Nepal and Australia, has resulted in official forward-backward translations of the instruments and manuals (available upon request from the authors) to English and Nepali, in which cultural applicability of items was also taken into account. Further research should indicate whether the PAI-CY 13–17 is indeed applicable and valid in these countries.

Conclusions

Based on initial psychometric tests, the PAI-CY 13–17 appears to have acceptable measurement properties, although more work with larger samples is needed, for example to assess whether the items comprise a unidimensional scale. It is possible to implement the current version of the PAI-CY 13–17 in Dutch low vision services, enabling more data collection and more extensive understanding of its psychometric properties. Acceptability of the PAI-CY 13–17 to end-users should be carefully monitored, especially if the changes suggested in this study are going to be incorporated.

Acknowledgements

We greatly thank all participating parents and adolescents for their contributions.

Abbreviations

- AC

Acceptance/self-consciousness

- CASP

Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation

- CO

Communication

- FI

Finances

- FVQ_CYP_NL

Dutch version of the Functional Vision Questionnaire for Children and Young People

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- LT

Leisure time

- MO

Mobility

- PAI-CY

Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcome measures

- SC

Social contacts

- SL

School

- SR

Self-reliance

- VI

Visual impairment

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

GvR and RvN contributed to the inception and design of the study. EE recruited participants and collected the data. EE and RvN contributed to the statistical analyses. EE drafted the manuscript. GvR and RvN provided substantial feedback on the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Royal Dutch Visio/Novum.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Valderas JM, Alonso J. Patient reported outcome measures: a model-based classification system for research and clinical practice. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(9):1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santana MJ, Feeny D. Framework to assess the effects of using patient-reported outcome measures in chronic care management. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23(5):1505–1513. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, Guyatt G, Ferrans CE, Halyard MY, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(2):179–193. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Ou LX, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:Artn 311. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravens-Sieberer U, Auquier P, Erhart M, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Bruil J, et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(8):1347–1356. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedell G. Further validation of the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP) Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2009;12(5):342–351. doi: 10.3109/17518420903087277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tadic V, Cooper A, Cumberland P, Lewando-Hundt G, Rahi JS. Vision-related quality of life G. Development of the functional vision questionnaire for children and young people with visual impairment: The FVQ_CYP. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2725–2732. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khadka J, Ryan B, Margrain TH, Court H, Woodhouse JM. Development of the 25-item Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for Children (CVAQC) The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;94(6):730–735. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.171181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birch EE, Cheng CS, Felius J. Validity and reliability of the Children’s Visual Function Questionnaire (CVFQ) Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2007;11(5):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane GM, Marella M, Keeffe JE, Lamoureux EL. The Impact of Vision Impairment for Children (IVI_C): validation of a vision-specific pediatric quality-of-life questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(3):1632–1640. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Castaneda YS, Wernimont SM, Liebermann L, Cheng-Patel CS, et al. Development of pediatric eye questionnaires for children with eye conditions. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;200:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rainey L, Elsman EBM, van Nispen RMA, van Leeuwen LM, van Rens G. Comprehending the impact of low vision on the lives of children and adolescents: A qualitative approach. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(10):2633–2643. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1292-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsman EBM, van Nispen RMA, van Rens G. Feasibility of the Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth (PAI-CY) and Young Adults (PAI-YA) with a visual impairment: a pilot study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0677-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsman EB, Tadić V, Peeters CF, van Rens GH, Rahi JS, van Nispen RM. Cross-cultural validation of the Functional Vision Questionnaire for Children and Young People (FVQ_CYP) with visual impairment in the Dutch population: challenges and opportunities. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2019;19(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0875-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . ICD-10: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision. Geneva: WHO; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tadic V, Cooper A, Cumberland P, Lewando-Hundt G, Rahi JS. Vision-related quality of life g. Measuring the quality of life of visually impaired children: first stage psychometric evaluation of the novel VQoL_CYP instrument. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0146225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesudovs K, Burr JM, Harley C, Elliott DB. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science. 2007;84(8):663–674. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318141fe75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AS, Vik FN, Chinapaw MJM, Uijtdewilligen L, Verloigne M, Fernandez-Alvira JM, et al. Test-retest reliability and construct validity of the ENERGY-child questionnaire on energy balance-related behaviours and their potential determinants: the ENERGY-project. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2011;8:Artn 136. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsman EB, van Nispen RM, van Rens GH. Psychometric evaluation of the Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth (PAI-CY) 0–2 years with visual impairment. Quality of Life Research. 2020;29(3):775–781. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02343-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsman EBM, van Nispen RMA, van Rens GH. Psychometric evaluation of a new proxy-instrument to assess participation in children aged 3–6 years with visual impairment: PAI-CY 3-6. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2019;39(5):378–391. doi: 10.1111/opo.12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elsman EBM, van Rens GHMB, van Nispen RMA. Psychometric properties of a new intake questionnaire for visually impaired young adults: The Participation and Activity Inventory for Young Adults (PAI-YA) PLos One. 2018;13(8):e0201701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elsman EB, Peeters CF, van Nispen RM, van Rens GH. Network analysis of the Participation and Activity Inventory for Children and Youth (PAI-CY) 7–12 years with visual impairment. Translational Vision Science & Technology. 2020;9(6):19. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.6.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but Low Kappa .1. The problems of 2 paradoxes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990;43(6):543–549. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90158-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cicchetti DV, Feinstein AR. High agreement but Low Kappa .2. Resolving the Paradoxes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990;43(6):551–558. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90159-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flight L, Julious SA. The disagreeable behaviour of the kappa statistic. Sheffield: The University of Sheffield; 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.