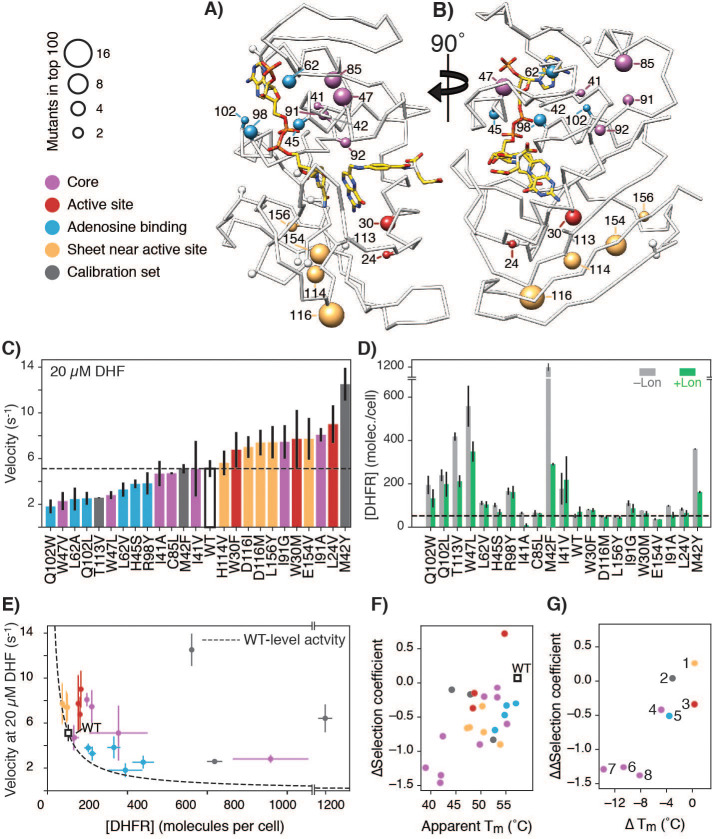

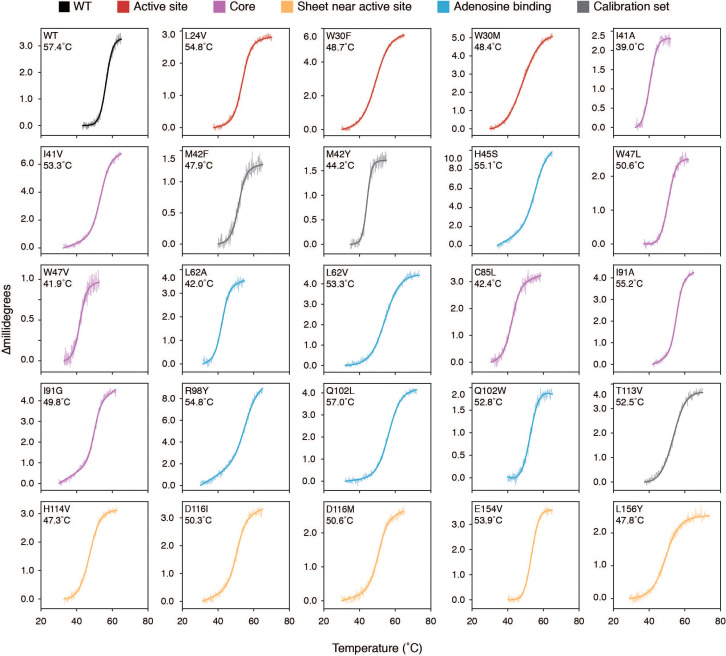

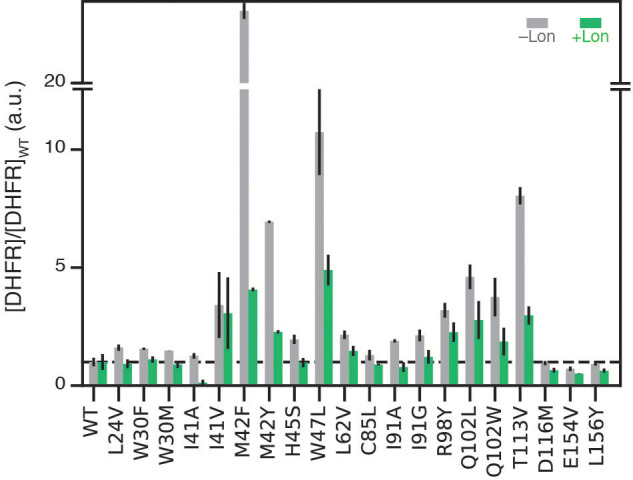

Figure 4. Advantageous mutations arise from an interplay of increased enzymatic velocity and increased abundance in the absence of Lon.

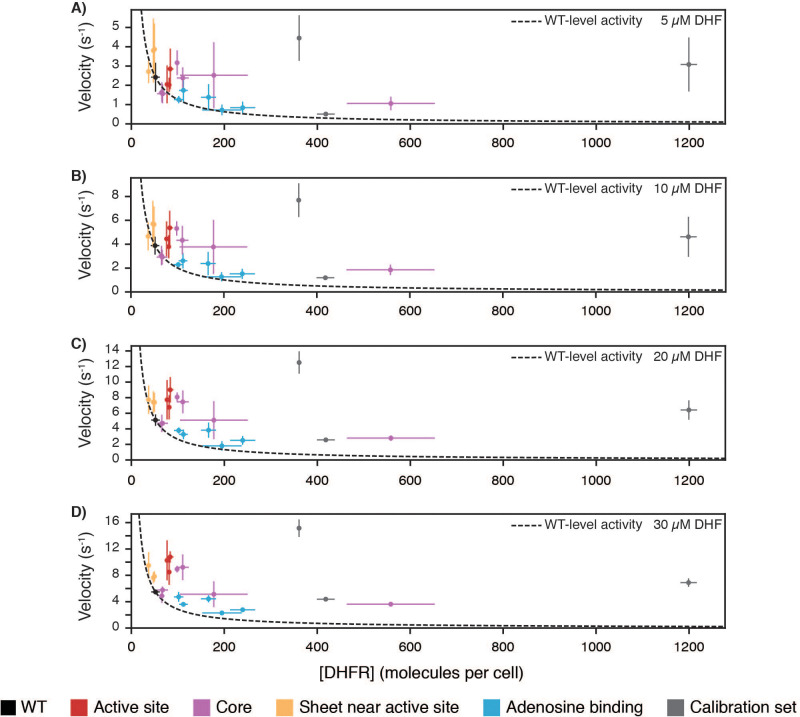

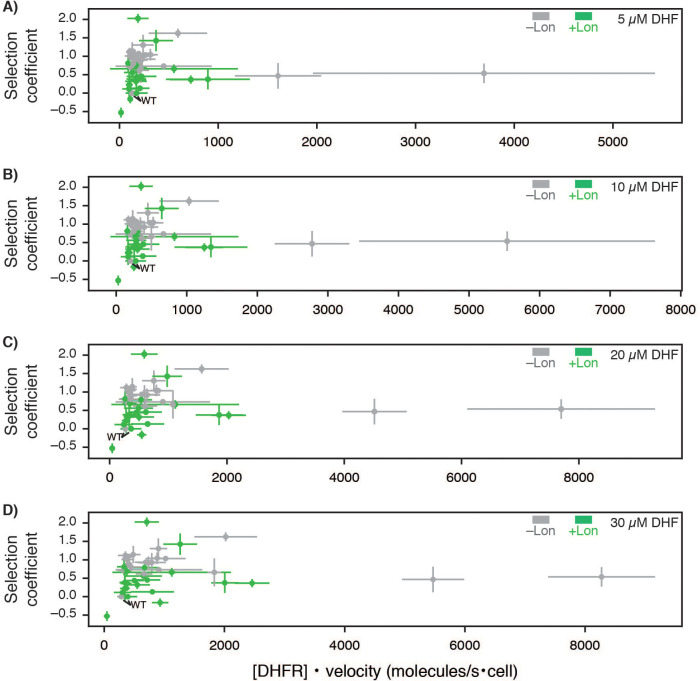

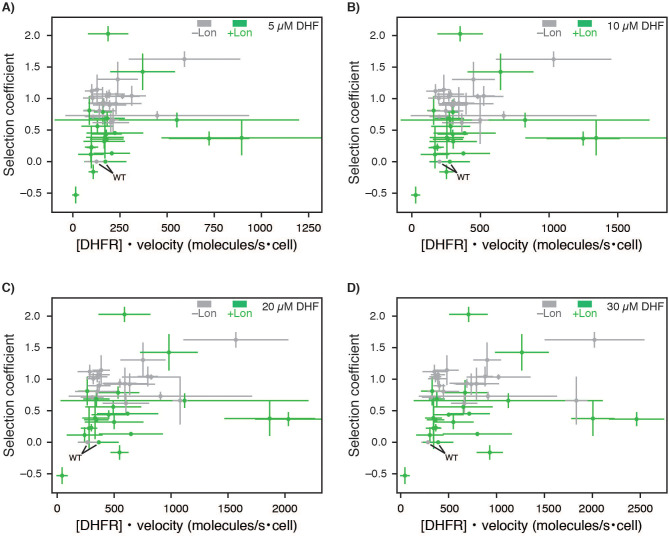

(A) DHFR structure with mutational hot-spots. For positions with two or more top 100 advantageous mutations in the absence of Lon, the beta carbon is depicted as a sphere scaled according to the number of top mutations. For mutants selected for in vitro characterization, the beta carbon is colored according to its location in the DHFR structure: core (purple), surface beta-sheet (gold), proximal to the adenine ring on NADPH (blue), or proximal to the active site and M20 loop (red). Positions for advantageous mutants from the calibration set are depicted in dark grey. (B) The structure from A) rotated 90° clockwise. (C) In vitro velocities of purified DHFR wild-type and point mutants measured at 20 µM DHF. Bars are colored in reference to the hot-spots in A). Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation from three independent experiments (Materials and methods). The dashed line represents the velocity of WT DHFR. (D) DHFR cellular abundance calculated from the lysate DHFR activity in Figure 4—figure supplement 2 and in vitro kinetics with purified enzyme (see Materials and methods). Error bars represent the cumulative percent error (standard deviation) from three independent experiments for velocity and three biological replicates for lysate activity. Data are shown in both the -Lon (light grey) and +Lon (green) conditions. The dashed line represents the WT expression level of DHFR in the –Lon background. Mutants are in the same order as in C) (see Figure 4—source data 2; four mutants were not measured). (E) Cellular abundance of DHFR vs. in vitro velocities of purified DHFR wild-type and point mutants measured at 20 µM DHF. Points are colored as in A). Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation from three independent experiments (Materials and methods). The dashed line represents WT-level DHFR activity, i.e. DHFR abundance/velocity pairs whose product is equivalent to [DHFR]WT • velocityWT. (F) Correlation between in vitro Tm values and in vivo ∆selection coefficients for DHFR wild-type and characterized mutants. Points are colored as in A). (G) ∆Tm values and ∆∆selection coefficient for mutations at the same position. Points representing comparison between mutants are numbered as follows: 1) D116I-M, 2) M42Y-F, 3) W30M-F, 4) I91G-A, 5) Q102W-L, 6) L62A-V, 7) I41A-V, 8) W47V-L.

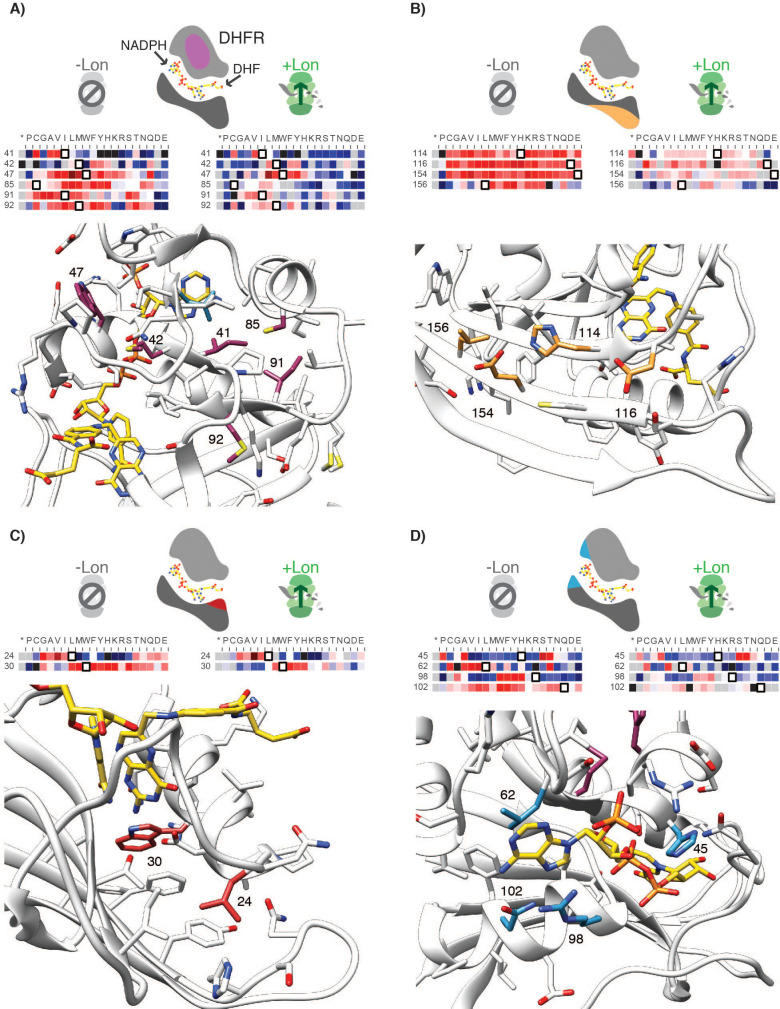

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Structural context for hotspot residues from Figure 4.

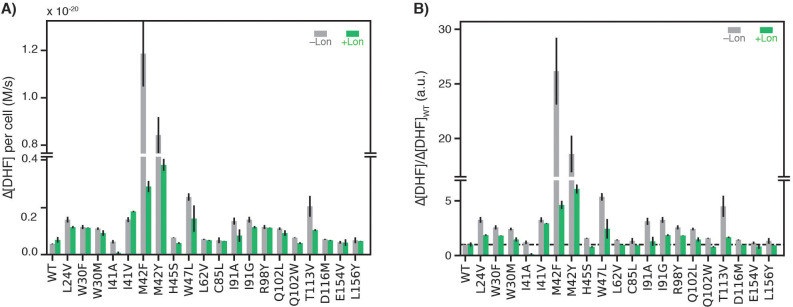

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Lysate activity for DHFR wild-type and point mutants on the selection plasmid.

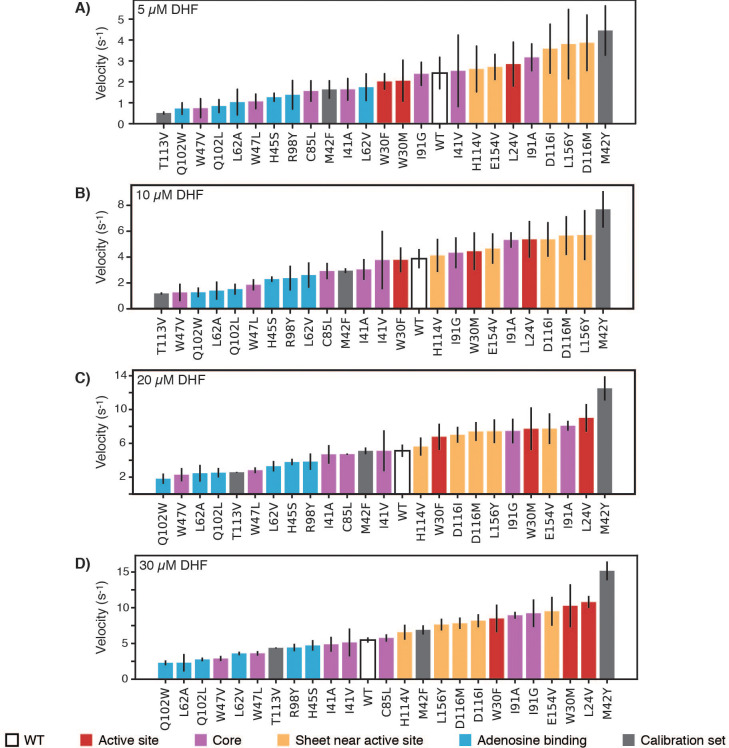

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. In vitro velocities of purified DHFR wild-type and point mutants.

Figure 4—figure supplement 4. Soluble cellular abundance for DHFR wild-type and point mutants on the selection plasmid.

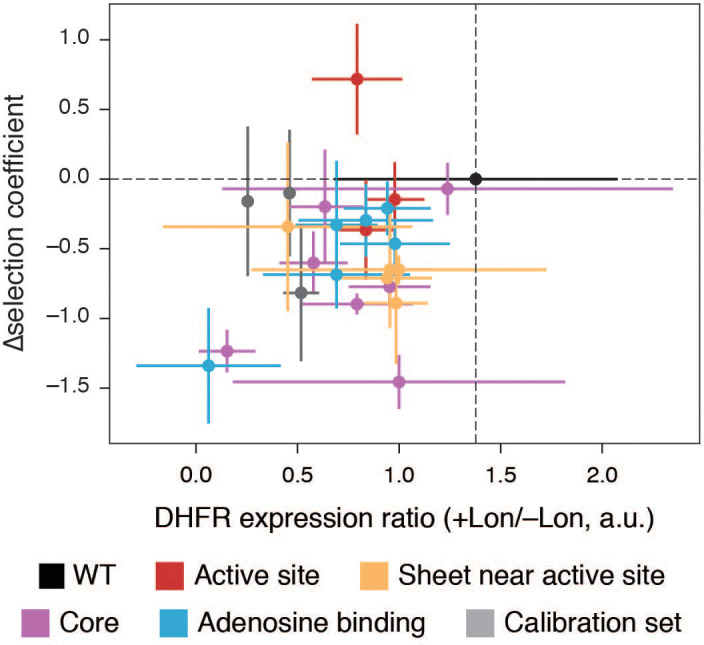

Figure 4—figure supplement 5. Lon impact as ∆selection coefficient versus change in DHFR abundance ±Lon.