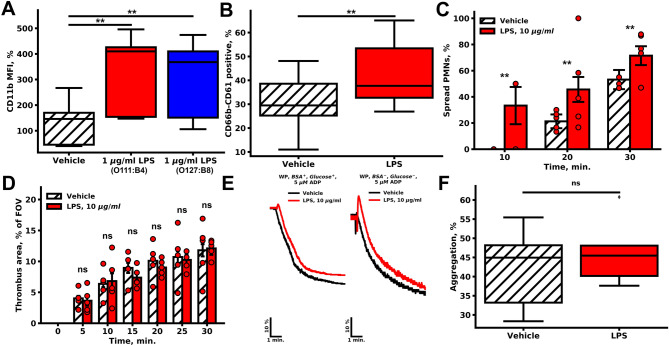

Figure 1.

Effects of LPSs on PMN and platelet activity. (A, B) Flow cytometry of platelet and PMN suspension. (A) Pre-incubation with LPSs of different origins (red—1 µg/ml E. coli O111:B4, blue—1 µg/ml E. coli O127:B8) resulted in the increased CD11b fluorescence in comparison to the vehicle (n = 10). (B) LPSs increased the amount of CD66b-CD61 positive events (n = 10). (C, D) For microscopy experiments, whole blood was perfused through parallel-plate flow chamber with fibrillar collagen coating (spread PMN and thrombus area quantification is described in methods); (C) LPSs significantly increased the amount of highly spread PMNs (n = 5); (D) pre-incubation with LPSs non-significantly decreased thrombus area at wall shear rate 200 s−1 (n = 5). For (C, D) bars represent mean, whiskers represent SEM, significance was calculated by Mann–Whitney test, n = 5, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (E–F) Light transmission aggregometry; (E) characteristic aggregation curves of washed platelets (n = 5); (F) Maximum platelet aggregation in citrated PRP upon stimulation with 5 μM of ADP. Statistical significance was calculated by the Wilcoxon test, n = 10.